What We Leave Behind

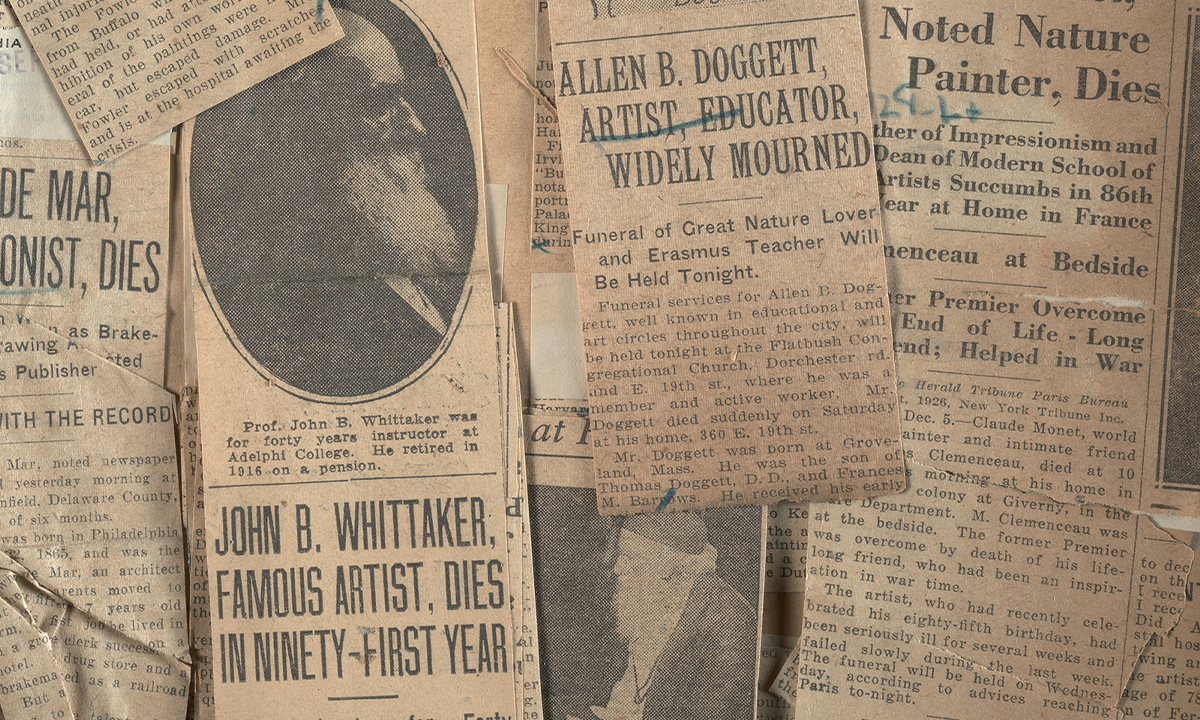

A new book explores the deaths of artists and the ex-con turned Metropolitan Museum of Art staffer who collected their obituaries. Obits in scrapbook from 1926, including obit for Claude Monet from the New York Herald Tribune. From "Deaths of Artists" by Jim Moske, courtesy of Blast Books

Obits in scrapbook from 1926, including obit for Claude Monet from the New York Herald Tribune. From "Deaths of Artists" by Jim Moske, courtesy of Blast Books

Jim Moske

Deaths of Artists

Blast Books, 128 pages, $40

Like newspaper crime blotters, I’ve long held that public obituaries are a sadly unheralded literary subgenre.

While blotter entries condense a novel’s worth of human drama and conflict into a hundred-word narrative, obituaries serve a very different and much trickier purpose. Instead of recounting a single event, obituaries set out to assess an entire life in a few short paragraphs. They cement forever what was valuable and memorable about the deceased’s time among the living, and determine how someone will be remembered when they no longer have any say in the matter. Consider the recent death of O.J. Simpson. Reading the obits, it was clear he will be remembered for his role in a sensational murder trial, but only in passing as a football legend and sometimes actor. In the art of the obituary, sordid scandal and the tragic float to the top, whether the subject was famous or not.

This is one of several threads snaking through Jim Moske’s new book, “Deaths of Artists.” Despite what the title might suggest, “Deaths of Artists” is far more wide-ranging than a simple collection of archival obituaries memorializing long-forgotten painters and sculptors. The book dives into museum culture and administration, yellow journalism, the capriciousness of fame, the myths and sad realities of the “starving artist” archetype. It is also the story of the unlikely figure whose personal mission made the book possible.

In 2018, Moske, a Metropolitan Museum of Art archivist, was researching another project when he stumbled across two massive scrapbooks in the Met’s vaults. It wasn’t clear what they were, or why they were there, but when he opened the first volume, he found the pages were lined with yellowed, crumbling century-old newspaper clippings. One in particular caught his eye:

FAMOUS ARTIST DIES PENNILESS AND ALL ALONE

Practically penniless and seemingly without friends, Mrs. Imogene Robinson Morrell, one of the most noted women painters of this country . . . died early today in her humble room in a cheap boarding house.

Carefully flipping through the brittle pages, he soon discovered both volumes contained nothing but artists’ obituaries. Hundreds and hundreds of obituaries.

“As I continued to look,” Moske writes in his introduction,

I saw a few stately remembrances of art world luminaries whose works remain familiar beacons in museum galleries today…But many others told stories of the decease of artists who were celebrated in their own time but have since fallen from fashion and are hardly remembered today. The majority recounted the passing away of people now completely forgotten.

Curious, he began following clues around the archive to uncover who was responsible for the scrapbooks. He soon zeroed in on Arthur D’Hervilly, who’d been a Met employee around the turn of the 20th century. That name then set Moske off on another project to learn what he could about D’Hervilly. What he found ties the book together, creating far more than an archival curiosity.

Thanks to his fine calligraphy and facility with numbers, in the late 19th century, Arthur D’Hervilly had solid employment as an accountant while living in his mother’s Philadelphia boarding house. In 1882, he was convicted of stealing an estimated $15,000 from his employer and sentenced to a year of hard labor.

Upon his release from prison, D’Hervilly was determined to become an artist. While not without talent, surviving as an artist has never been easy for anyone. In 1894, he took a job as a security guard at the Met. At the time the Met, founded only 25 years earlier, wasn’t the imposing and monolithic cultural institution it is today. Again, on account of his beautiful calligraphy, head for figures and interest in art, D’Hervilly quickly ascended through a variety of positions within the museum’s administration. In a variant of the well-worn “started in the mailroom” rags-to-riches storyline, the ex-con was eventually named the Met’s assistant curator of paintings.

Readers and Moske alike can only speculate why, but in 1906, D’Hervilly contacted The National Press Intelligence Company, a news-clipping service, asking them to send him the death notices of anyone identified as an artist. Whenever he received a new package, he dutifully pasted the notices into his growing scrapbooks, resulting in a chronological record of the deaths of over a thousand artists great and not-so-much. Again, we can only speculate why, but at some point, as he was building his morbid collection, he also abruptly began signing his name as the much more ostentatious (and baffling) “A. B. de St. M. D’Hervilly.”

D’Hervilly maintained his obsessive collection until his own death in 1919, after which his colleagues at the Met continued his good work for another decade.

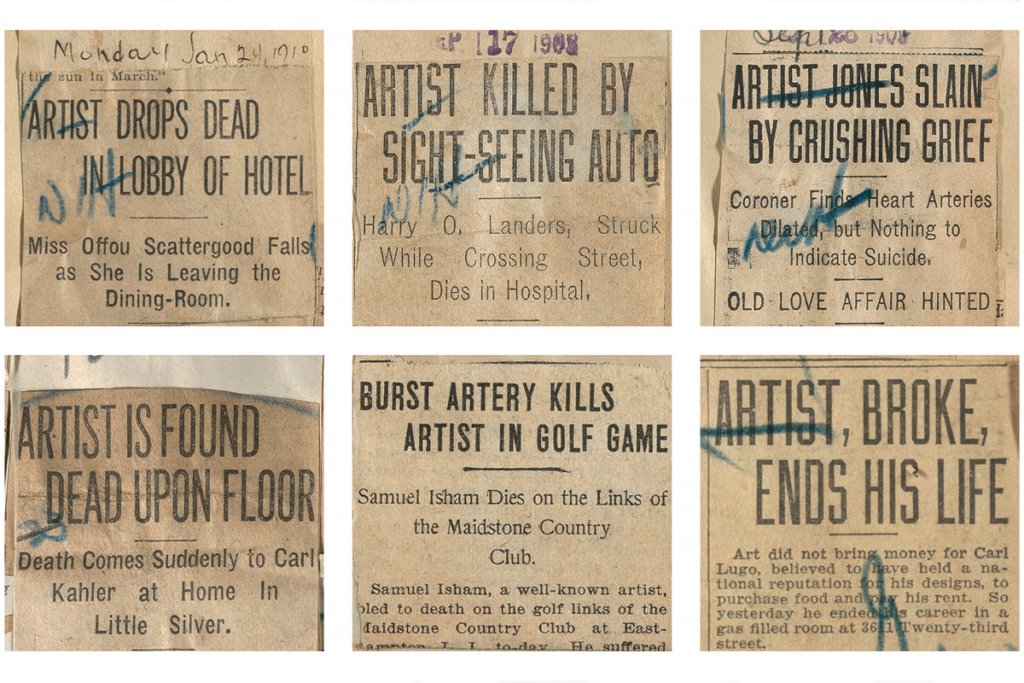

For the most part contemporary newspaper obituaries are composed from simple templates filled out by grieving family members or, when possible, cribbed from Wikipedia pages. In the heyday of yellow journalism, however, things were a bit livelier. Sensationalism, lurid detail and the occasional bit of embellishment were what made the tabloids so popular. In many cases the line between an obituary and a crime blotter entry grew awfully blurry, as D’Hervilly’s collection made abundantly clear. The headlines alone, often marked by a deadpan gallows humor, were designed to tap directly into the readers’ ghoulish curiosity:

“Artist Killed While Hurrying to Catch a Train”

“Artist Fires Bullet into Brain while in Hotel Dining Room”

“Gives His Body for Dog Meat”

“Strange Death of Well-known Artist”

“Woman Artist Dies Enveloped in Flames”

A little editorializing on the part of the tabloid writers was never discouraged either. Under the headline “ARTIST SLAIN; DEATH HAND ON WALL IS CLUE,” we learn the victim, John Keyes, had been stabbed 20 times. The brutality of the murder didn’t dissuade the reporter from describing Keyes as “one of the drifting thousands who draw pictures — not salaries… His books and sketches were the dignity of his gloomy room.”

Like all good biographies, Moske’s meticulously researched account of D’Hervilly’s life veers off into assorted detours: explorations of the careers of the lesser-known artists from the scrapbooks, museum gossip, Vasari’s 16th century work “The Lives of Artists,” how clipping services work. All of it paints a portrait (if you will) of the fickle nature of the art world of the time, a world that’s changed very little over the ensuing century.

If the scrapbooks act as a kind of memento mori, then so does the book itself, which is illustrated with images of scrapbook pages, lurid tabloid headlines, samples of D’Hervilly’s handwriting and the work of some of these forgotten artists. The images give the story Moske is telling a distinct tangibility.

In many cases the line between an obituary and a crime blotter entry grew awfully blurry, as D’Hervilly’s collection made abundantly clear.

When D’Hervilly died in 1919, he was buried in an unmarked grave. Met administrators released a laudatory statement and small, sober notices appeared in The New York Times and other local papers. None of them featured splashy, tawdry, attention-grabbing headlines. In all likelihood, apart from his colleagues and friends, D’Hervilly, like most of the artists in his scrapbooks, was forgotten the second readers turned the page to check last night’s scores. For a century, he remained nothing but a name on an employee ledger until Moske went looking, finding not only A. B. de St. M. D’Hervilly, but all those other, equally forgotten lives he’d so carefully preserved.

The lesson within the story of D’Hervilly and his peculiar scrapbooks is that we are what we leave behind. Sometimes it’s not very pretty. Sometimes it’s meager, sometimes it’s amazing. But it’s still a mark, proving we’d been here. If we’re lucky, at some point down the line, someone will rediscover it, whatever it is, and maybe remember us for a few minutes.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.