Violence, USA: The Warfare State and the Brutalizing of Everyday Life

Warlike values and the social mind-set they legitimize have become the primary currency of our market-driven culture, which takes as its model a Darwinian shark tank in which only the strong survive.

By Henry A. Giroux, TruthoutThis piece originally appeared atTruthout.

Since 9/11, the war on terror and the campaign for homeland security have increasingly mimicked the tactics of the enemies they sought to crush. Violence and punishment as both a media spectacle and a bone-crushing reality have become prominent and influential forces shaping American society. As the boundaries between “the realms of war and civil life have collapsed,” social relations and the public services needed to make them viable have been increasingly privatized and militarized.(1) The logic of profitability works its magic in channeling the public funding of warfare and organized violence into universities, market-based service providers and deregulated contractors. The metaphysics of war and associated forms of violence now creep into every aspect of American society.

As the preferred “instrument of statecraft,”(2) war and its intensifying production of violence cross borders, time, space and places. Seemingly without any measure of self-restraint, state-sponsored violence flows and regroups, contaminating both foreign and domestic policies. One consequence of the permanent warfare state is evident in the public revelations concerning a number of war crimes committed recently by US government forces. These include the indiscriminate killings of Afghan civilians by US drone aircraft; the barbaric murder of Afghan children and peasant farmers by American infantrymen infamously labeled as “the kill team”;(3) disclosures concerning four American Marines urinating on dead Taliban fighters; and the recent uncovering of photographs showing “more than a dozen soldiers of the 82nd Airborne Division’s Fourth Brigade Combat Team, along with some Afghan security forces, posing with the severed hands and legs of Taliban attackers in Zabul Province in 2010.”(4) And, shocking even for those acquainted with standard military combat, there is the case of Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, who “walked off a small combat outpost in Kandahar province and slaughtered 17 villagers, most of them women and children and later walked back to his base and turned himself in.”(5) Mind-numbing violence, war crimes and indiscriminate military attacks on civilians on the part of the US government are far from new, of course, and date back to infamous acts such as the air attacks on civilians in Dresden along with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.(6) Military spokespersons are typically quick to remind the American public that such practices are part of the price one pays for combat and are endemic to war itself.

The history of atrocities committed by the United States in the name of war need not be repeated here, but some of these incidents have doubled in on themselves and fueled public outrage against the violence of war.(7) One of the most famous was the My Lai massacre, which played a crucial role in mobilizing anti-war protests against the Vietnam War. Even dubious appeals to national defense and honor can provide no excuse for mass killings of civilians, rapes and other acts of destruction that completely lack any justifiable military objective. Not only does the alleged normative violence of war disguise the moral cowardice of the warmongers, it also demonizes the enemy and dehumanizes soldiers. It is this brutalizing psychology of desensitization, emotional hardness and the freezing of moral responsibility that is particularly crucial to understand, because it grows out of a formative culture in which war, violence and the dehumanization of others becomes routine, commonplace and removed from any sense of ethical accountability.

It is necessary to recognize that acts of extreme violence and cruelty do not represent merely an odd or marginal and private retreat into barbarism. On the contrary, warlike values and the social mindset they legitimate have become the primary currency of a market-driven culture, which takes as its model a Darwinian shark tank in which only the strong survive. At work in the new hyper-social Darwinism is a view of the other as the enemy; an all-too-quick willingness in the name of war to embrace the dehumanization of the other; and an only too-easy acceptance of violence, however extreme, as routine and normalized. As many theorists have observed, the production of extreme violence in its various incarnations is now a show and source of profit for Hollywood moguls, mainstream news, popular culture and the entertainment industry and a major market for the defense industries.(8)

This pedagogy of brutalizing hardness and dehumanization is also produced and circulated in schools, boot camps, prisons, and a host of other sites that now trade in violence and punishment for commercial purposes, or for the purpose of containing populations that are viewed as synonymous with public disorder. The mall, juvenile detention facilities, many public housing projects, privately owned apartment buildings and gated communities all embody a model of failed sociality and have come to resemble proto-military spaces in which the culture of violence and punishment becomes the primary order of politics, fodder for entertainment and an organizing principle for society. Even public school reform is now justified in the dehumanizing language of national security, which increasingly legitimates the transformation of schools into adjuncts of the surveillance and police state.(9)

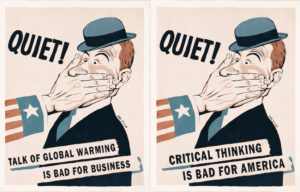

The privatization and militarization of schools mutually inform each other as students are increasingly subjected to disciplinary apparatuses which limit their capacity for critical thinking, mold them into consumers, test them into submission, strip them of any sense of social responsibility and convince large numbers of poor minority students that they are better off under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system than being valued members of thy public schools.. All of these spaces and institutions, from malls to schools, are coming to resemble war zones. They produce and circulate forms of symbolic and real violence that dissolve the democratic bonds of social reciprocity just as they appeal incessantly to the market-driven egocentric interests of the autonomous individual, a fear of the other and a stripped-down version of security that narrowly focuses on personal safety rather than collective security nets and social welfare.

Under such a war-like regime of privatization, militarism and punishing violence, it is not surprising that the Hollywood film “The Hunger Games” has become a box office hit. The film and its success are symptomatic of a society in which violence has become the new lingua franca. It portrays a society in which the privileged classes alleviate their boredom through satiating their lust for violent entertainment and, in this case. a brutalizing violence waged against children. While a generous reading might portray the film as a critique of class-based consumption and violence given its portrayal of a dystopian future society so willing to sacrifice its children, I think, in the end, the film more accurately should be read as depicting the terminal point of what I have called elsewhere the suicidal society (a suicide pact literally ends the narrative).(10)Given Hollywood’s rush for ratings, the film gratuitously feeds enthralled audiences with voyeuristic images of children being killed for sport. In a very disturbing opening scene, the audience observes children killing each other within a visual framing that is as gratuitous as it is alarming. That such a film can be made for the purpose of attaining high ratings and big profits, while becoming overwhelming popular among young people and adults alike, says something profoundly disturbing about the cultural force of violence and the moral emptiness at work in American society. Of course, the meaning and relevance of “The Hunger Games” rest not simply with its production of violent imagery against children, but with the ways these images and the historical and contemporary meanings they carry are aligned and realigned with broader discourses, values and social relations. Within this network of alignments, risk and danger combine with myth and fantasy to stoke the seductions of sadomasochistic violence, echoing the fundamental values of the fascist state in which aesthetics dissolves into pathology and a carnival of cruelty.

Within the contemporary neoliberal theater of cruelty, war has expanded its poisonous reach and moves effortlessly within and across America’s national boundaries. As Chris Hedges has pointed out brilliantly and passionately, war “allows us to make sense of mayhem and death” as something not to be condemned, but to be celebrated as a matter of national honor, virtue and heroism.(11) War takes as its aim the killing of others and legitimates violence through an amorally bankrupt mindset in which just and unjust notions of violence collapse into each other. Consequently, it has become increasingly difficult to determine justifiable violence and humanitarian intervention from unjustifiable violence involving torture, massacres and atrocities, which now operate in the liminal space and moral vacuum of legal illegalities. Even when such acts are recognized as war crimes, they are often dismissed as simply an inevitable consequence of war itself. This view was recently echoed by Leon Panetta who, responding to the alleged killing of civilians by US Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, observed, “War is hell. These kinds of events and incidents are going to take place, they’ve taken place in any war, they’re terrible events and this is not the first of those events and probably will not be the last.”(12) He then made clear the central contradiction that haunts the use of machineries of war in stating, “But we cannot allow these events to undermine our strategy.”(13) Panetta’s qualification is a testament to barbarism because it means being committed to a war machine that trades in indiscriminate violence, death and torture, while ignoring the pull of conscience or ethical considerations. Hedges is right when he argues that defending such violence in the name of war is a rationale for “usually nothing more than gross human cruelty, brutality and stupidity.”(14)

War and the organized production of violence has also become a form of governance increasingly visible in the ongoing militarization of police departments throughout the United States. According to the Homeland Security Research Corp, “The homeland security market for state and local agencies is projected to reach $19.2 billion by 2014, up from $15.8 billion in fiscal 2009.”(15) The structure of violence is also evident in the rise of the punishing and surveillance state,(16) with its legions of electronic spies and ballooning prison population – now more than 2.3 million. Evidence of state-sponsored warring violence can also be found in the domestic war against “terrorists” (code for young protesters), which provides new opportunities for major defense contractors and corporations to become “more a part of our domestic lives.”(17) Young people, particularly poor minorities of color, have already become the targets of what David Theo Goldberg calls “extraordinary power in the name of securitization … [they are viewed as] unruly populations … [who] are to be subjected to necropolitical discipline through the threat of imprisonment or death, physical or social.”(18) The rhetoric of war is now used by politicians not only to appeal to a solitary warrior mentality in which responsibility is individualized, but also to attack women’s reproductive rights, limit the voting rights of minorities and justify the most ruthless cutting of social protections and benefits for public servants and the poor, unemployed and sick.

This politics and pedagogy of death begins in the celebration of war and ends in the unleashing of violence on all those considered disposable on the domestic front. A survival-of-the-fittest ethic and the utter annihilation of the other have now become normalized, saturating everything from state policy to institutional practices to the mainstream media. How else to explain the growing taste for violence in, for example, the world of professional sports, extending from professional hockey to extreme martial arts events? The debased nature of violence and punishment seeping into the American cultural landscape becomes clear in the recent revelation that the New Orleans Saints professional football team was “running a ‘bounty program’ which rewarded players for inflicting injuries on opposing players.”(19) In what amounts to a regime of terror pandering to the thrill of the crowd and a take-no-prisoners approach to winning, a coach offered players a cash bonus for “laying hits that resulted in other athletes being carted off the field or landing on the injured player list.”(20)

The bodies of those considered competitors, let alone enemies, are now targeted as the war-as-politics paradigm turns America into a warfare state. And even as violence flows out beyond the boundaries of state-sponsored militarism and the containment of the sporting arena, citizens are increasingly enlisted to maximize their own participation and pleasure in violent acts as part of their everyday existence — even when fellow citizens become the casualties. Maximizing the pleasure of violence with its echo of fascist ideology far exceeds the boundaries of state-sponsored militarism and violence. Violence can no longer be defined as an exclusively state function since the market in its various economic and cultural manifestations now enacts its own violence on numerous populations no longer considered of value. Perhaps nothing signals the growing market-based savagery of the contemporary moment more than the privatized and corporate-fueled gun culture of America.Gun culture now rules American values, if not also many of US domestic policies. The National Rifle Association is the emerging symbol of what America has come to represent, perfectly captured in T-shirts worn by its followers that brazenly display the messages “I hate welfare” and “If any would not work neither should he eat.”(21) The relationship Americans have to guns may be complicated, but the social costs are less nuanced and certainly more deadly. In a country with “90 guns for every 100 people,” it comes as no surprise, as Gary Younge points out, that “more than 85 people a day are killed with guns and more than twice that number are injured with them.”(22) The merchants of death trade in a formative and material culture of violence that causes massive suffering and despair while detaching themselves from any sense of moral responsibility. Social costs are rarely considered, in spite of the endless trail of murders committed by the use of such weapons and largely inflicted on poor minorities. Violence has become not only more deadly, but flexible, seeping into a range of institutions, cannibalizing democratic values and merging crime and terror. As Jean and John Comaroff point out, under such circumstances a social order emerges that “appears ever more impossible to apprehend, violence appears ever more endemic, excessive and transgressive and police come, in the public imagination, to embody a nervous state under pressure.”(23) Public disorder becomes both a spectacle and an obsession and is reflected in advertising and other everyday venues — advertising can even “transform nightmare into desire…. [Yet] violence is never just a matter of the circulation of images. Its exercise, legitimate or otherwise, tends to have decidedly tangible objectives. And effects.”(24)

An undeniable effect of the warmongering state is the drain on public coffers. The United States has the largest military budget in the world and “in 2010-2011 accounted for 40% of national spending.”(25) The Eisenhower Study Group at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International Studies estimates that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have cost the American taxpayers between $3.7 trillion and $4.4 trillion. What is more, funding such wars comes with an incalculable price in human lives and suffering. For example, the Eisenhower Study estimated that there has been over 224,475 lives lost, 363,383 people wounded and seven million refugees and internally displaced people.(26) But war has another purpose, especially for neoconservatives who want to destroy the social state. By siphoning funds and public support away from much-needed social programs, war, to use David Rothkopf’s phrase, “diminishes government so that it becomes too small to succeed.”(27)

The warfare state hastens the dismantling of the social state and its limited safety net, creating the conditions for the ultra-rich, mega corporations and finance capital to appropriate massive amounts of wealth, income and power. This has resulted in, as of 2012, the largest ever increase in inequality of income and wealth in the United States.(28) Structural inequalities do more than distribute wealth and power upward to the privileged few. They also generate forms of collective violence accentuated by high levels of uncertainty and anxiety, all of which, as Michelle Brown points out, “makes recourse to punishment and exclusion highly seductive possibilities.”(29) The merging of the punishing and financial state is partly legitimated through the normalization of risk, insecurity and fear in which individuals not only have no way of knowing their fate, but also have to bear individually the consequences of being left adrift by neoliberal capitalism.

In American society, the seductive power of the spectacle of violence is fed through a framework of fear, blame and humiliation that circulates widely in popular culture. The consequence is a culture marked by increasing levels of inequality, suffering and disposability. There is not only a “surplus of rage,” but also a collapse of civility in which untold forms of violence, humiliation and degradation proliferate. Hyper-masculinity and the spectacle of a militarized culture now dominate American society – one in which civility collapses into rudeness, shouting and unchecked anger. What is unique at this historical conjuncture in the United States is that such public expression of hatred, violence and rage “no longer requires concealment but is comfortable in its forthrightness.”(30) How else to explain the support by the majority of Americans for state sanctioned torture, the public indifference to the mass incarceration of poor people of color, or the public silence in the face of police violence in public schools against children, even those in elementary schools? As war becomes the organizing principle of society, the ensuing effects of an intensifying culture of violence on a democratic civic culture are often deadly and invite anti-democratic tendencies that pave the way for authoritarianism.

In addition, as the state is hijacked by the financial-military-industrial complex, the “most crucial decisions regarding national policy are not made by representatives, but by the financial and military elites.”(31) Such massive inequality and the suffering and political corruption it produces point to the need for critical analysis in which the separation of power and politics can be understood. This means developing terms that clarify how power becomes global even as politics continues to function largely at the national level, with the effect of reducing the state primarily to custodial, policing and punishing functions — at least for those populations considered disposable.

The state exercises its slavish role in the form of lowering taxes for the rich, deregulating corporations, funding wars for the benefit of the defense industries and devising other welfare services for the ultra-rich. There is no escaping the global politics of finance capital and the global network of violence that it has created. Resistance must be mobilized globally and politics restored to a level where it can make a difference in fulfilling the promises of a global democracy. But such a challenge can only take place if the political is made more pedagogical and matters of education take center stage in the struggle for desires, subjectivities and social relations that refuse the normalizing of violence as a source of gratification, entertainment, identity and honor.

War in its expanded incarnation works in tandem with a state organized around the production of widespread violence. Such a state is necessarily divorced from public values and the formative cultures that make a democracy possible. The result is a weakened civic culture that allows violence and punishment to circulate as part of a culture of commodification, entertainment and distraction. In opposing the emergence of the United States as both a warfare and a punishing state, I am not appealing to a form of left moralism meant simply to mobilize outrage and condemnation. These are not unimportant registers, but they do not constitute an adequate form of resistance.What is needed are modes of analysis that do the hard work of uncovering the effects of the merging of institutions of capital, wealth and power and how this merger has extended the reach of a military-industrial-carceral and academic complex, especially since the 1980s. This complex of ideological and institutional elements designed for the production of violence must be addressed by making visible its vast national and global interests and militarized networks, as indicated by the fact that the United States has over a 1,000 military bases abroad. Equally important is the need to highlight how this military-industrial-carceral and academic complex uses punishment as a structuring force to shape national policy and everyday life.

Challenging the warfare state also has an important educational component. C. Wright Mills was right in arguing that it is impossible to separate the violence of an authoritarian social order from the cultural apparatuses that nourish it. As Mills put it, the major cultural apparatuses not only “guide experience, they also expropriate the very chance to have an experience rightly called ‘our own.'”(32) This narrowing of experience shorn of public values locks people into private interests and the hyper-individualized orbits in which they live. Experience itself is now privatized, instrumentalized, commodified and increasingly militarized. Social responsibility gives way to organized infantilization and a flight from responsibility.

Crucial here is the need to develop new cultural and political vocabularies that can foster an engaged mode of citizenship capable of naming the corporate and academic interests that support the warfare state and its apparatuses of violence, while simultaneously mobilizing social movements in order to challenge and dismantle its vast networks of power. One central pedagogical and political task in dismantling the warfare state is, therefore, the challenge of creating the cultural conditions and public spheres that would enable the American public to move from being spectators of war and everyday violence to being informed and engaged citizens.

Unfortunately, major cultural apparatuses such as public and higher education, which have been historically responsible for educating the public, are becoming little more than market-driven and militarized knowledge factories. In this particularly insidious role, educational institutions deprive students of the capacities that would enable them to not only assume public responsibilities, but also actively participate in the process of governing. Without the public spheres for creating a formative culture equipped to challenge the educational, military, market and religious fundamentalisms that dominate American society, it will be virtually impossible to resist the normalization of war as a matter of domestic and foreign policy.

Any viable notion of resistance to the current authoritarian order must also address the issue of what it means pedagogically to imagine a more democratic-oriented notion of knowledge, subjectivity and agency and what might it mean to bring such notions into the public sphere. This is more than what Bernard Harcourt calls “a new grammar of political disobedience.”(33) It is a reconfiguring of the nature and substance of the political so that matters of pedagogy become central to the very definition of what constitutes the political and the practices that make it meaningful. Critical understanding motivates transformative action and the affective investments it demands can only be brought about by breaking into the hard-wired forms of common sense that give war and state supported violence their legitimacy. War does not have to be a permanent social relation, nor the primary organizing principle of everyday life, society and foreign policy.

The war of all against all and the social Darwinian imperative to respond positively only to one’s own self-interests represent the death of politics, civic responsibility and ethics and the victory of a “failed sociality.” The existing neoliberal social order produces individuals who have no commitments, except to profit, disdain social responsibility and loosen all ties to any viable notion of the public good. This regime of punishment and privatization is organized around the structuring forces of violence and militarization, which produce a surplus of fear, insecurity and a weakened culture of civic engagement – one in which there is little room for reasoned debate, critical dialogue and informed intellectual exchange.

America understood as a warfare state prompts a new urgency for a collective politics and a social movement capable of negating the current regimes of political and economic power, while imagining a different and more democratic social order. Until the ideological and structural foundations of violence that are pushing American society over the abyss are addressed, the current warfare state will be transformed into a full-blown authoritarian state that will shut down any vestige of democratic values, social relations and public spheres. At the very least, the American public owes it to its children and future generations, if not the future of democracy itself, to make visible and dismantle this machinery of violence while also reclaiming the spirit of a future that works for life rather than the death worlds of the current authoritarianism, however dressed up they appear in the spectacles of consumerism and celebrity culture. It is time for educators, unions, young people, liberals, religious organizations, and other groups to connect the dots, educate themselves and develop powerful social movements that can restructure the fundamental values and social relations of democracy, while putting into place the institutions and formative cultures that make it possible. Stanley Aronowitz is right in arguing that:

The system survives on the eclipse of the radical imagination, the absence of a viable political opposition with roots in the general population and the conformity of its intellectuals who, to a large extent, are subjugated by their secure berths in the academy [and while] we can take some solace in 2011, the year of the protester … it would be premature to predict that decades of retreat, defeat and silence can be reversed overnight without a commitment to what may be termed a “a long march” though the institutions, the workplaces and the streets of the capitalist metropoles.[34]

The current protests among young people, workers, the unemployed, students, and others are making clear that this is not – indeed, cannot be – only a short-term project for reform, but must constitute a political and social movement of sustained growth, accompanied by the reclaiming of public spaces, the progressive use of digital technologies, the development of democratic public spheres, new modes of education and the safeguarding of places where democratic expression, new identities and collective hope can be nurtured and mobilized. Without broad political and social movements standing behind and uniting the call on the part of young people for democratic transformations, any attempt at radical change will more than likely be cosmetic.

Any viable challenge to the new authoritarianism and its theater of cruelty and violence must include developing a variety of cultural discourses and sites where new modes of agency can be imagined and enacted, particularly as they work to reconfigure a new collective subject, modes of sociality and “alternative conceptualizations of the self and its relationship to others.”(35) Clearly, if the United States is to make a claim on democracy, it must develop a politics that views violence as a moral monstrosity and war as virulent pathology. How such a claim to politics unfolds remains to be seen. In the meantime, resistance proceeds, especially among the young people who now carry the banner of struggle against the encroachment of an authoritarianism that is working hard to snuff out all vestiges of democratic life.

Footnotes:

1. Melinda Cooper, “Life as Surplus: Biotechnology & Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era” (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008), p. 92. 2. Andrew Bacevich, “After Iraq, War is US,” ReadersNewsService (December 20, 2011). Online here. 3. Henry A. Giroux, “‘Instants of Truth’: The ‘Kill Team’ Photos and the Depravity of Aesthetics,” Afterimage: Journal of Media Arts and Cultural Criticism (Summer 2011), pp. 4-8. 4. Thom Shanker and Graham Bowley, “Images of G.I.s and Remains Fuel Fears of Ebbing Discipline,” New York Times (April 18, 2012). Online here. 5. Craig Whitlock and Carol Morello, “US Army Sergeant Faces 17 Murder Counts in Afghan Killings,” Toronto Star (March 22, 2012). Online here. 6. Mark Selden and Alvin Y. So, eds., “War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century” (Denver: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004); Jeremy Brecher, Jill Cutler and Brendan Smith, eds., “In the Name of Democracy: American War Crimes in Iraq and Beyond” (New York: Macmillan, 2005); Jordan J. Paust, “Beyond the Law: The Bush Administration’s Unlawful Responses in the ‘War’ on Terror,” (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007); and Andrew Bacevich, “Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War” (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010). 7. Joachim J. Savelsberg and Ryan D. King, “American Memories: Atrocities and the Law” (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2011); Carl Boggs, “The Crimes of Empire: The History and Politics of an Outlaw Nation” (London: Pluto Press, 2010). 8. See for example, Catherine A. Lutz, “Homefront: A Military City and the American Twentieth Century” (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002); Carl Boggs, ed., “Masters of War: Militarism and Blowback in the Era of the America Empire” (New York: Routledge, 2003); Chalmers Johnson, “The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy and the End of the Republic” (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004); Andrew J. Bacevich, “The New American Militarism” (Oxford University Press, 2005); Nick Turse, “How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives” (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2008); and Andrew J. Bacevich, “Washington Rules: America’s Path To Permanent War” (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010). 9. Joe Klein and Condoleezza Rice, “US Education Reform and National Security” (Washington: Council on Foreign Relations, 2012), online here. For a brilliant critique of this right-wing warmongering screed, which is really a front for privatizing schools, see Jennifer Fisher, “‘The Walking Wounded’: Youth, Public Education and the Turn to Precarious Pedagogy,” Review of Education, Pedagogy & Cultural Studies 33:5 (November-December 2011), pp. 379-432. 10. I want to thank Grace Pollock for this idea. See also: Henry A. Giroux, “The ‘Suicidal State’ and the War on Youth,” Truthout (April 10, 2012). Online here. 11. Chris Hedges, “Murder Is Not an Anomaly in War,” TruthDig.com (March 19, 2012). Online here. 12. Phil Stewart, “Death Penalty Possible in Afghan Massacre: Panetta,” Reuters (March 12, 2012). Online here. 13. Steward, “Death Penalty.” 14. Hedges, “Murder Is Not an Anomaly.” 15. Robert Johnson, “Pentagon Offers US Police Full Military Hardware,” ReaderSupportedNews (December 11, 2011). Online here. 16. Dana Priest and William Arkin, “Top Secret America: The Rise of the New American Security State” (New York: Little Brown, 2011). 17. Andrew Becker and G.W. Schulz, “Cops Ready for War,” ReaderSupportedNews (December 21, 2011). Online here. 18. David Theo Goldberg, “The Threat of Race: Reflections on Racial Neoliberalism” (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), p. 334. 19. Richard McAdam, “On Bounties and the Integrity of Professional Sports,” SportsCardForum (April 2012). Online here. 20. McAdam, “On Bounties.” 21. Gary Younge, “America’s Deadly Devotion to Guns,” The Guardian UK (April 16, 3012). Online here. 22. Younge, “America’s Deadly Devotion.” 23. Jean and John Comaroff, “Criminal Obsessions, after Foucault: Postcoloniality, Policing and the Metaphysics of Disorder,” Critical Inquiry 30 (Summer 2004), pp. 803, 804. 24. Comaroff, “Criminal Obsessions,” p. 804, 808. 25. Stanley Aronowitz, “The Winter of Our Discontent,” Situations IV, no.2 (Spring 2012), p. 57. 26. The complete findings of the study are available at www.costofwar.com. 27. David Rothkopf, “Power, Inc.: The Epic Rivalry Between Big Business and Government – and the Reckoning That Lies Ahead” (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2012), p. 258. 28. Paul Krugman, “American’s Unlevel Field,” New York Times (January 8, 2012), p. A19; Nicholas Lemann, “Evening the Odds: Is there a Politics of Inequality?” The New Yorker (April 23, 2012), online here. See also Charles M. Blow, “Inconvenient Income Inequality,” New York Times (December 16, 2011), p. A25, online here; David Moberg, “Anatomy of the 1%,” In These Times (December 15, 2011), online here; Hope Yen and Laura Wides-Munoz, “US Poorest Poor at Record Highs,” ReaderSupportedNews (November 4, 2011), online here. 29. Michelle Brown, “The Culture of Punishment: Prison, Society and Spectacle” (New York: New York University Press, 2009), p. 194. 30. Brown, “The Culture of Punishment,” p. 196. 31. Aronowitz, “The Winter of Our Discontent,” p. 69. 32. C. Wright Mills, “The Cultural Apparatus, The Politics of Truth: Selected Writings of C. Wright Mills” (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 204. 33. Bernard Harcourt, “Occupy’s New Grammar of Political Disobedience,” The Guardian UK (November 30, 2011). Online here. 34. Stanley Aronowitz, “The Winter of Our Discontent,” p. 68. 35. Brown, “The Culture of Punishment,” p. 207.

This article may not be republished without permission from Truthout.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.