The Trillion-Dollar Fantasy at the Heart of the Global Economy

It may be a heady time for the tech titans in Cupertino, but we should worry when a super-sized market sector is effectively fueled by magical thinking. People use iPads to take an augmented reality tour of the main building during the grand opening of the Apple Park Visitor Center at Apple, Inc.'s new Cupertino, Calif. headquarters on Nov. 17, 2017. (Eric Risberg / AP Photo)

People use iPads to take an augmented reality tour of the main building during the grand opening of the Apple Park Visitor Center at Apple, Inc.'s new Cupertino, Calif. headquarters on Nov. 17, 2017. (Eric Risberg / AP Photo)

There are approximately 1 trillion stars in the Andromeda Galaxy, one for every dollar in Apple’s current market capitalization. Andromeda is 2.5 million light-years distant from our own Milky Way, however, so by the time any Andromedans read this, Apple will be long gone, melted or drowned like the rest of the artifacts of our Ozymandian civilization.

Meanwhile, Apple’s Cupertino, Calif., headquarters, a $5 billion 1970s shopping-mall food court, is nicknamed “the spaceship,” though apparently not because the space cadets it houses can’t seem to stop walking into the glass walls. For the privilege of hosting the world’s most valuable public company and 25,000 of its employees, the city of Cupertino collects an extraordinary $17,000 a year in tax revenue, something akin to the annual property tax on a nice five-bedroom in Nassau County, N.Y.

A recent proposal to charge the company a head tax, increasing its annual contribution to $9.4 million—a burdensome two hundredths of 1 percent of Apple’s 2017 net income—was quashed on the vague promise that Apple would one day fund a local Hyperloop, a fantastical transportation technology that would put small train cars inside large versions of the pneumatic tubes from the drive-through bank your mom used to deposit checks into in 1986. It would move six or seven people at a time in a mere five minutes along a route that a tram carrying a hundred could traverse in ten.

I guess what I am saying is that this number, 1 trillion, is absurd.

It is also not terribly meaningful, except perhaps as a signpost on the route to the next recession. It is not, for instance, tied to any particular measurement of Apple’s performance as a company. Apple’s total balance-sheet assets are about $375 billion. At something like its present rate of profitability, it would take two more decades to earn a trillion bucks, and there is no particular reason to imagine it can indefinitely maintain current income levels.

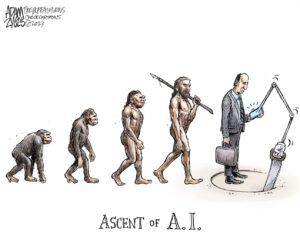

The iPhone is more than a decade old and hasn’t improved meaningfully in several generations. Newer iterations have mostly grown more inconvenient, as Apple has turned its innovative energies to selling dongles and otherwise scamming customers into its proprietary peripherals ecosystem to goose revenues. Its last really good device, the iPod, is dead. All that remains of that elegant little improvement on a Walkman is the bloated, gaseous carcass of iTunes, around which its poor customers clutter like seabed scavengers around a decomposing whale.

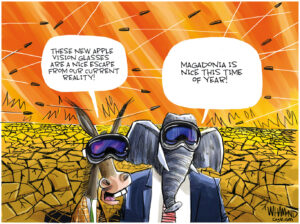

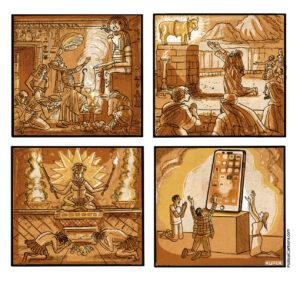

Rather, its market capitalization, a pure reflection of stock price, is a product of speculation. Oh, sure, institutional investors care about quarterly earnings, but no one is really making bets on new products in the pipeline. They’re just watching pigeons fly like augurs in the ancient world. They are not investing in Apple; they are investing in Apple stock, something between a separate emanation and a magical élan vital.

There are plenty of overvalued companies, and Apple is only the most ridiculous because of the combination of the transcendent hugeness of its valuation and the cultish devotion of its most avid consumers, who respond to the company’s ever-blander aesthetic like John Ruskin swooning over 19th-century Venice. But we should worry when whole trillion-dollar pieces of our economies are effectively make-believe, when, as was the case in 2007-2008 and in the dot-com blowup before that, a small spark of panic anywhere can swiftly cause a run on the whole rickety thing.

And we should worry as well because companies like Apple, besides making gadgets, have essentially locked up huge libraries of the cultural patrimony of our era—our music and literature and correspondence and movies and television. What happens if one, or several, of these new for-profit Alexandrias starts to burn? Forget the instantaneous evaporation of notional wealth. Who is going to run into Amazon’s sweltering server farms to rescue the scrolls? (The threat of a “digital dark age” is underdiscussed, despite the post-apocalyptic tendencies of contemporary art and politics, although it occasionally pops up in science fiction novels, such as Charlie Stross’ 2006 “Glasshouse.”)

The overvaluation of tech stocks and the dangers of a sector-wide collapse—even a modest correction—is only a small piece of the over-financialization of the entire global economic system. It is, for instance, only a symptom of our fixation on firms’ equity market capitalization that lets us call Apple the first trillion-dollar company in the first place. JPMorgan Chase & Co., for example, has a market cap of just under $400 billion, but that bank alone has $2.5 trillion in assets under management. Well, you can argue that that is really other people’s money, but so is Apple’s own trillion.

And in reality, Apple can do considerably less with all that equity than JPM can do with its piles upon piles of OPM. Globally, there are 30-odd banks with managed assets near or in excess of $1 trillion. The largest bank in China has over $4 trillion. Much of this money swirls about in the vast oceans of global credit markets, upon which equities like stocks are just the white froth on top of a fathomless sea. Money upon money upon money, without chains of title or clear owners—the pure communism of the super-super rich.

At some point in the future, if we survive, I expect historians will look back at us roughly as we look back at pre-Reformation Europe, a society so bound up by the universality of its common faith that from its own limited vantage it could not see the coming crackup. That said, I do think that everyone alive today, with the exception of paid professional optimists like the irrepressible Steven Pinker, senses the static charge of the coming storm. Nevertheless, it is hard to appreciate the true immensity of the holy architecture of global capital, and it’s no remedy to observe, correctly, that it is mostly made up. After all, gods do not have to be actual to be real.

It’s become a cliché to say that Facebook, a modest $500 billion little brother to Apple, is more like a country than a company, populated by over 2 billion users and allegedly casting a deranging shadow of misinformation across the political systems of the world’s largest and most powerful nation-states. But Facebook’s subversion of notional national sovereignties is neither especially novel nor particularly egregious; it’s just very obvious because the company is run by a silly, callow and unsubtle young man. Financial firms, petrochemical companies, pharmaceutical concerns—they have all long transcended national borders, often working in the interests of powerful states, which are themselves generally unconcerned with any borders other than their own.

The question is what this will look like as this all begins to unravel, as the pressures of climate change drive the largest human migrations in history and the ability of national and international political institutions to defend the global flow of capital and trade begins to crack and fade. I haven’t the slightest inkling of an answer, but I know that it will not look like a trillion-dollar glass doughnut on a leafy campus beside a magic train.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.