Tom Hayden Fought for the Rights of All Living Things

The progressive activist compiled an impressive record in California and local politics—from 18 years in the state Capitol to a variety of community crusades. Even shelter animals benefited from his work.

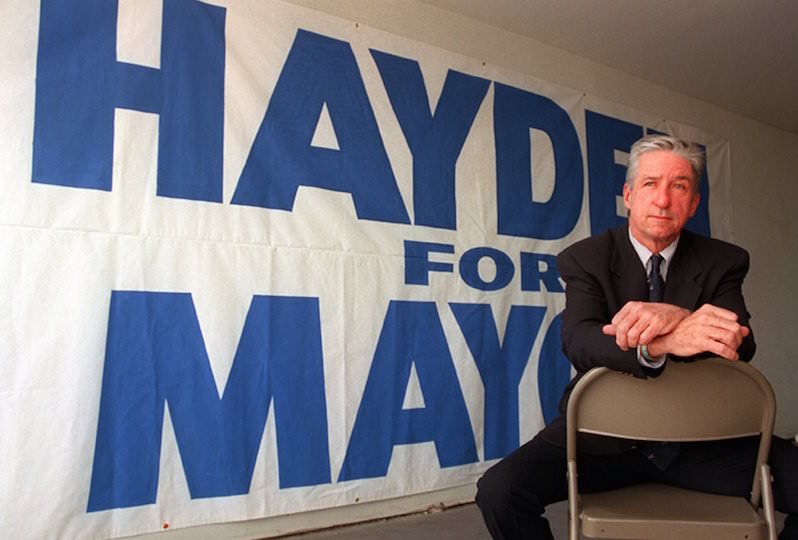

Tom Hayden, who died Sunday, served in the California Assembly (1982–1992) and the California Senate (1992–2000). In 1997, he ran for mayor of Los Angeles and lost to Republican incumbent Richard Riordan. (Steve W. Grayson / AP)

Tom Hayden and I happened to be on the same flight from Los Angeles to Sacramento as he prepared to begin his first year in the state Legislature in 1982.

We sat next to each other and began to talk. For me, it was an unexpected treat. I always enjoyed the company of a man who, rather than talk about himself, seemed so interested in what others had to say.

That, in fact, was one of his great qualities, rare in public figures — especially in elected politics, the business Hayden was about to enter. He was nice to people, charming in an unassuming way.

On the plane to the capital, Hayden questioned me on how the Legislature worked. He wanted hints on getting along with his new colleagues, pitfalls to avoid, opportunities to do good. How would he, the famous antiwar radical, be treated by Sacramento’s conventional establishment? They were, after all, conventional politicians, including supporters of the Vietnam War he had opposed, and were still angry over the anti-war demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention. Hayden had been a leader in that protest.

Here’s what happened after he got to Sacramento: While never one of the guys, Hayden compiled an impressive record in 10 years in the California Assembly and eight in the California Senate. He got millions of dollars for his district to improve the quality of Santa Monica Bay and rebuild the Santa Monica and Malibu piers. He helped delay University of California and Cal State University tuition increases. He led efforts that extended laws against sexual harassment. Also included in a long list of legislation was his Hayden Act, which extended the time shelters must keep abandoned animals alive, giving volunteers more time to find them homes.

I got to know him best when he was involved in the frustrating work of local politics. I followed him around during his losing campaign for Los Angeles mayor in 1997. As a state senator, he campaigned through neighborhoods in an easy, relaxed manner, making some of his more controversial proposals sound palatable. Even when meeting with the editors of the Los Angeles Times, he passed the test of convincing his stuffy listeners that he wasn’t a threat to them and the city.

These were mild efforts compared to his greatest Los Angeles crusade, taking up the cause of Salvadoran gang members in the abysmally crowded slums of a part of the city known as Pico-Union. The violent gangs were being targeted by the Los Angeles Police Department’s Rampart Division anti-gang officers, some of whom turned out to be violent and crooked themselves. The public strongly supported the police, and anyone standing up for gang members was scorned and headed for political death.

Caught up in all this was a Salvadoran gang member, Alex Sanchez, who served time in juvenile camps and state prisons for crimes including car theft and possession of weapons. A community leader, he was also trying to negotiate peace between rival gangs. It was clear, Hayden felt, that the Rampart gang cops and the immigration service disapproved of Sanchez’s leadership ability and peacemaking and were cooperating illegally to send him back to bloody El Salvador.

The Times was investigating the Rampart cops intensely. Hayden wanted us to also dig into the Sanchez case. By then, defense of Sanchez had become a movement extending beyond Pico-Union.

Hayden came to the paper with a few other Sanchez supporters to meet with me and other editors. He recalled our meeting in his book “Street Wars.” Hayden said we editors “sat sphinxlike listening to our tale. I wondered if we were becoming too emotional, too conspiratorial.” But Hayden convinced us, and we quickly put reporters on the Sanchez story.

Police continued their efforts to get rid of Sanchez. He was charged in 2009 with taking part in a 2006 gang murder. At this point, Sanchez was a well-respected leader in efforts to stop gang violence. It took three more years, but in 2012, charges were dropped in what prosecutors admitted was a flawed case.

This was not a cause that attracted national attention. Helping the immigrant community organize was tough, gritty work for Hayden. It took him to Central America on an arduous trip to meet gang members in their homelands, where they had been deported, visiting the prisons where many of them were kept.

In recent years, his health was failing. He looked older and thinner. But he persevered, just as he had during the Vietnam War protest era and the civil rights movement. That activism and his leadership in the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests helped shape national politics.

But Tom Hayden will also be remembered for his other, less well-known accomplishments — by many in the still crowded Pico-Union slums, by swimmers and surfers at the Santa Monica beach and in shelters where volunteers seek homes for the abandoned animals that his Hayden Act helped save.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.