Thinking Beyond the Age of Fire

Human society without fire is unthinkable. But a new book says we need to think of a world where fire gives way to electricity. Most of what humanity has achieved has depended on fire. (snty-tact via Wikimedia Commons)

Most of what humanity has achieved has depended on fire. (snty-tact via Wikimedia Commons)

Most of what humanity has achieved has depended on fire. (snty-tact via Wikimedia Commons)

This Creative Commons-licensed piece first appeared at Climate News Network.

LONDON — In December, in an unprecedented demonstration of international unity, 195 countries adopted the first-ever, universal, legally-binding agreement to take action on climate change.

It was a decision that, to be truly effective, requires an obligation to think again, at the most fundamental level, about how humans manage energy and maintain the essential comforts of civilisation.

Humans cannot go back to the beginning and start again, but if they had to, Walt Patterson’s new book would be as fundamental a guide to the challenges as any.

It doesn’t contain many helpful prescriptions about the most efficient exploitation of the emerging technologies that could deliver renewable energy, or deliver more bang for the megabuck of investment. But that’s not the point.

Patterson’s point is that a new start means a fresh attitude, and Electricity vs Fire is as nice a statement of the essential simplicity – and the scale – of the challenge as I have yet seen.

Patterson first made his name 45 years ago as an informed critic of the nuclear industry, and as one of the early voices of Friends of the Earth. He starts simply by reducing what humans do to six simple and very easily described physical actions.

- Humans control heat flow: that is, they put on clothes when cold, and open windows when hot.

- They adjust local temperatures: that is, they put a log on a fire or turn down a thermostat.

- Third, they make light: by candle, by electric lamp.

- Fourth, they exert force: they lift weights and push open the door.

- Fifth: they move things: this sounds like exerting force – and it requires force – but the whole of civilisation is based on traffic, on commerce, on the flow of objects, so you can see why he makes it a separate physical action.

- And lastly, humans manage information: they talk, listen, reason, exchange ideas, amass data, create mental pictures of worlds they cannot see, construct histories, and compose paradigms that help them work out how things came to be as they are, and how they could be different.

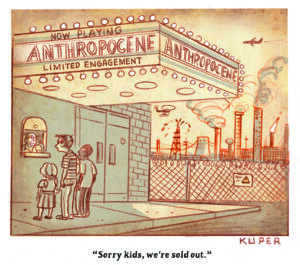

Everything Homo sapiens has achieved in the last 70,000 years involves all of, but only, those six actions. And for most of those 700 centuries, humans have achieved everything using only tools, and fire, and – but only for a century or so – electricity.

And much of that electricity is made for us with help from fire – coal, oil, gas fire – which delivers carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere in quantities so vast that global temperatures have begun to rise and the once-stable global climate has begun to change in ways that, ultimately, threaten civilisation itself.

So the trick is to switch to electrical supplies that don’t depend on fire. We’ve started. But the logic of this book insists, to really change, we need to think the whole process through from the beginning, and understand that humanity’s profound dependence on fire must end.

Chance of change

Having listed the six physical energy-dependent actions that define us as humans, Patterson pursues each of them, as histories, and as opportunities that really do offer change.

The arrival of the combined cycle gas turbine in continuous operation, for instance, meant that generating stations could be smaller, better and clean enough to be close to users, and built in shorter time. Where natural gas was cheap, you could have electricity.

But such innovation pointed to even smaller, better and cleaner ways, and once a “renewable” – a wind turbine or photovoltaic array – is in existence, electricity becomes not a commodity, but a process, with options for new ways of financing it.

Patterson explores the inventive ways we can control heat efficiently without fire, and concedes that domestic cooking “is not, in the main, a significantly wasteful way to use fire. In rich countries the waste occurs much more in the increasing prevalence of processed food.”

“Infrastructure changes only slowly. But minds can change in an instant. Today could be the day you start thinking beyond the Fire Age”

He delivers analysis, and instances better ways of doing things, but the value of a book such as this is that it simply frames the important questions.

On the exertion of force, for instance: “Many people might now argue that most of the undertakings that use lots of brute force, such as large dams and river diversions, mountain-top removal coal mining, tar sands extraction or uranium mining, are at best ill-advised and frequently destructive.

“Closer examination suggests that such undertakings proceed only because those promoting them do not pay the costs of their actions.”

He points out that the whole global economy is based on fire and its consequences, and the consumer society exists to turn resources into waste. The phrase “consumer durables” becomes an oxymoron.

New values needed

To move beyond this “stupid and dangerous” situation, humans “need to rethink the whole value structure that governs what we do and how.”

This is more easily said than done, but he foresees human activity switching towards natural systems, functioning not with the brute force of fire but the elegance of electricity.

One bit of this reviewer murmurs: “Good luck with that!” But another bit endorses his final words: “Infrastructure changes only slowly. But minds can change in an instant. Today could be the day you start thinking beyond the Fire Age.”

Tim Radford, a founding editor of Climate News Network, worked for The Guardian for 32 years, for most of that time as science editor. He has been covering climate change since 1988.

Dig, Root, GrowThis year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

This spring, stand with our journalists.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.