They Don’t Decorate Carcasses

A long-lost anti-war novel by Louis-Ferdinand Celine gets the English translation it deserves. Louis-Ferdinand Celine. Photograph from Agence Meurisse / Bibliothèque nationale de France / Alamy

Louis-Ferdinand Celine. Photograph from Agence Meurisse / Bibliothèque nationale de France / Alamy

War

By Louis-Ferdinand Celine

Translated by Charlotte Mandell

New Directions, 144 pages, $15.95

When Louis-Ferdinand Celine, his wife Lucette and cat Bebert fled Paris in a mad rush in 1944, the notorious author of “Death on the Installment Plan” left behind over 5,000 pages of unpublished handwritten manuscripts. It’s believed that not long afterward, Oscar Rosembly, a journalist and member of the French Resistance, broke into Celine’s empty apartment and pilfered the abandoned papers. For nearly 80 years those papers were assumed to be lost to the winds, another cultural casualty of the war. Celine himself publicly mourned them until his death in 1961.

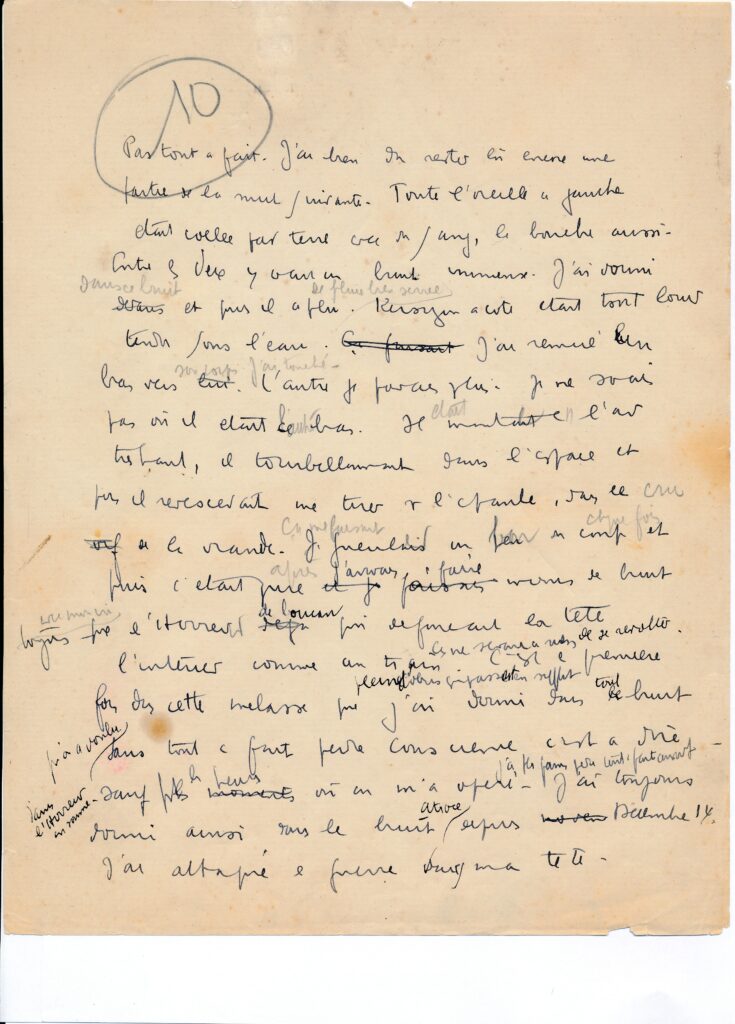

Then, in June of 2020, the executors of Celine’s literary estate were contacted by a lawyer representing a French journalist by the name of Jean-Pierre Thibaudat. The lawyer informed the executors, François Gibault and Véronique Chovin, that Thibaudat claimed to be in possession of all 5,324 pages of the purloined manuscripts. How exactly the material made it from Rosembly to Thibaudat, how many hands it passed through intact over the course of eight decades, remains a mystery. What mattered was that the manuscripts — including complete drafts of three unpublished novels — were safe. In literary circles this is what’s technically known as “a big honking whoop-dee-doo.”

Among the three novels was a short work titled “Guerre” (“War”) that Celine wrote in 1934, two years after the publication of his epic, phantasmagoric debut novel “Journey to the End of the Night.” Inspired by his experiences during and after WWI, “Journey” had taken a chainsaw to the weary formalism of French literature, and earned him a spot in the Pantheon. His ongoing influence has been acknowledged by the likes of Henry Miller, Kurt Vonnegut, Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Hubert Selby Jr., George Orwell, William Gaddis and other notables.

Celine was a relentless misanthropist, and he makes this clear in his novels. He was also a fierce pacifist, also evident in his novels.

Whether Celine considered “War” a finished novel is unknown, though some marginal notes and narrative quirks (character names that abruptly change, etc.) would indicate it’s an early draft. Other scholars argue it’s a mere sketch or the outline for a longer novel. Whatever the case, at some point he set it aside with those other unpublished works and refocused his attention. In 2022, Gallimard, Celine’s publisher through much of his career, released “War” in his native France. New Directions will be releasing Charlotte Mandell’s splendid English translation later this month.

The publication of a novel, long-lost or otherwise, by a reviled and unapologetic antisemite has always been a touchy call, perhaps now more than ever. Celine was a relentless misanthropist, and he makes this clear in his novels. He was also a fierce pacifist, also evident in his novels. But he never allowed his antisemitism to leak into his fiction. There isn’t a whiff of it in “War”s pages, but it doesn’t seem to matter. America’s major publishing houses have long been too squeamish to go anywhere near Celine. The fear has nothing to do with the quality of the work, which is undeniable, and everything to do with the character of the author. (At this point I will refrain from bringing up Walt Disney, Henry Ford, Eleanor Roosevelt or the word “hypocrisy.”) For this reason, Celine’s major novels have only appeared in the U.S. decades after their original French editions, and then only through indie or academic presses. We can be grateful that New Directions, which has released several Celine titles in the past, has a history of putting art above politics.

Far too often, the general consensus is that rediscovered lost novels by literary giants like Hemingway, James Baldwin or Henry Miller were, yeah, probably better off lost. This isn’t the case with “War,” a rare instance in which the novel lives up to the hype surrounding its rediscovery.

Celine’s novels have always paralleled his own picaresque life, and “War” seems to take place within a chapter break in “Journey to the End of the Night.” It’s a fictionalized account of the months he spent hospitalized after being wounded at Flanders in the early days of WWI. The novel’s uncharacteristic brevity offers a distillation of Celine’s signature themes. The corruption of those with the tiniest shred of power, the baseness of human motivations, a world in which everyone’s got a grift, and above all, the stupidity and madness of war — delivered with a humor and slapstick that’s black as tar.

The novel opens with an inimitably Celinian flourish. “I must have stayed there for part of the following night as well,” he writes. “My whole left ear was stuck to the ground with blood, my mouth too. Between the two there was an immense noise. I slept in this noise and then it rained, hard.”

Staggering away from a battlefield after suffering a serious head wound, Celine’s alter-ego Ferdinand deserts, or at least attempts to desert, the army. He stumbles around the countryside sliding into and out of delirium, plagued by the inescapable clanging and whistling in his head. “I caught the war in my head,” he writes. “It’s locked up inside my head.” That noise, which shifts and morphs and blends with the other sounds around him, becomes a character in itself, tormenting him throughout the book.

He eventually lands in a crowded military hospital in the small town of Peurdu-sur-la-Lys, where he’s cared for by Mademoiselle L’Espinasse. Sometimes gentle, sometimes sadistic, Mademoiselle L’Espinasse’s caregiving swings between hand jobs and deliberately painful catheterizations. (As Ferdinand discovers later, she’s also a necrophile.) Meanwhile he has to fend off an inexperienced doctor’s efforts to operate on him simply to get a little practice.

The novel’s uncharacteristic brevity offers a distillation of Celine’s signature themes.

“As for the other guys in the room,” Ferdinand muses about his fellow patients, “there were enough wounds for every taste, on every surface and at every depth, reservists for the most part but idiots all of them. Many of them did nothing but enter and exit, to the earth or heaven.”

Much of the story takes place during Ferdinand’s regular sojourns into town with his friend Cascade, a wardmate who’d been shot in the foot. Relieved to be freed from the hospital for a few hours, they hang out at a popular bar, wander about, and Ferdinand gets an earful about Cascade’s love-hate relationship with the girlfriend he’s forced into prostitution. Whether in town or the hospital, there remains no escape from the war. In the distance, the sound of gunfire and mortar shells is unrelenting, the hospital is overflowing with new casualties and glittering regiments of fresh-faced cannon fodder are always marching through the streets.

While he expects to be found out and executed for desertion, things take an unexpected turn when Ferdinand is instead presented with a medal for some fictional battlefield heroics. Acutely aware he’s a fraud, he nevertheless wears the medal with swaggering pride to earn the respect and admiration of the townsfolk and his fellow patients.

“You have the medal, it’s great,” Celine writes. “In the battle of loudmouths you’re finally winning in a big way, you have your special fanfare in your head, you’re half-gangrened, you’re rotten that goes without saying, but you’ve seen battlefields where they don’t decorate carcasses and you’re decorated, don’t forget that or you’re an ingrate, you’re gross vomit, dribbling ass scrapings, you’re not worth the paper they wipe you with.”

Celine had witnessed the brutality of war first hand, and this passage is in many ways a summation of both his pacifism and the bitter contempt that runs through most of his novels. Its rage is aimed at the hypocrisy of the politicians and generals who wage wars, as well as the civilians who cheer them on and fawn over medals (deserved or not), without ever directly experiencing war themselves.

Given the glut of godawful Celine translations out there, Charlotte Mandell deserves special praise.

While “War” is a comparatively straightforward work written before Celine’s prose evolved into the splintered, staccato imagist style that marked his later novels, it’s heavy use of colloquial ’30s gutter slang and other narrative idiosyncrasies make him one of the most daunting translation challenges in modern literature. Given the glut of godawful Celine translations out there, Charlotte Mandell deserves special praise. The recipient of both the Chevalier Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and The American Academy of Arts and Letters Thornton Wilder Prize for Translation, Mandell deftly captures Celine’s tone and rhythm while preserving the eccentricities that made him such a singular stylist. You get the sense that what you’re reading isn’t a simple transposition of words from one language into another, but precisely what Celine intended. It’s good news, then, that Mandell will also be translating “Londres,” the next of Celine’s rediscovered novels, scheduled for release by New Directions in 2026.

“War” is a quick but representative read, which makes it a fine introduction for readers hesitant to tackle Celine’s heftier novels. More importantly, it’s a cautionary, timely and unflinching portrait of a civilization that still considers war an exciting spectator sport pitting Good against Evil. Say what you will about his character, Celine knew better.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.