Plants and Fungi Are Being Driven to the Brink of Extinction

A new report warns of five key risks that are pushing ecosystems toward total collapse. Image: Adobe

Image: Adobe

Scientists’ understanding of how climate change and habitat loss could drive plant and fungi extinctions is being hamstrung by knowledge gaps in how many species currently exist, a new report warns.

More than 90% of fungi have yet to be found and formally described by scientists, according to a new report from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

The “State of the World’s Plants and Fungi” report, which is based on both peer-reviewed and preliminary studies, also says that almost half of all flowering plant species could be at risk of extinction.

Habitat and land-use changes are the biggest threat to plants and fungi, but climate change is expected to become an even larger issue in the future, the director of science at Kew tells Carbon Brief

Below, Carbon Brief outlines five key findings from the report.

1. Three in four unknown plant species are at risk of extinction

Thousands of new plant and fungi species are named by scientists each year, but many still remain unnamed.

Around 90% of fungi species have yet to be described, making this formal identification process particularly “urgent” for fungi, the report notes. It estimates that it would take 750-1,000 years to name all of the remaining unknown fungi species.

Thousands of plants remain unnamed, including up to 100,000 “vascular” plant species. (Vascular plants are a large group of plants that are characterised by having a vascular system for transporting water. This includes trees, shrubs, grasses and flowering plants.)

More than three in four plant species that have not yet been formally described by scientists are likely threatened with extinction, the report says.

The new research by Kew scientists analysed data from the World Checklist of Vascular Plants and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list of threatened species – a global assessment of the extinction risk status of different animals, plants and fungi. The report was launched during a three-day conference held in Kew Gardens in London this week.

The researchers examined the links between the year a plant species was formally described and its extinction risk.

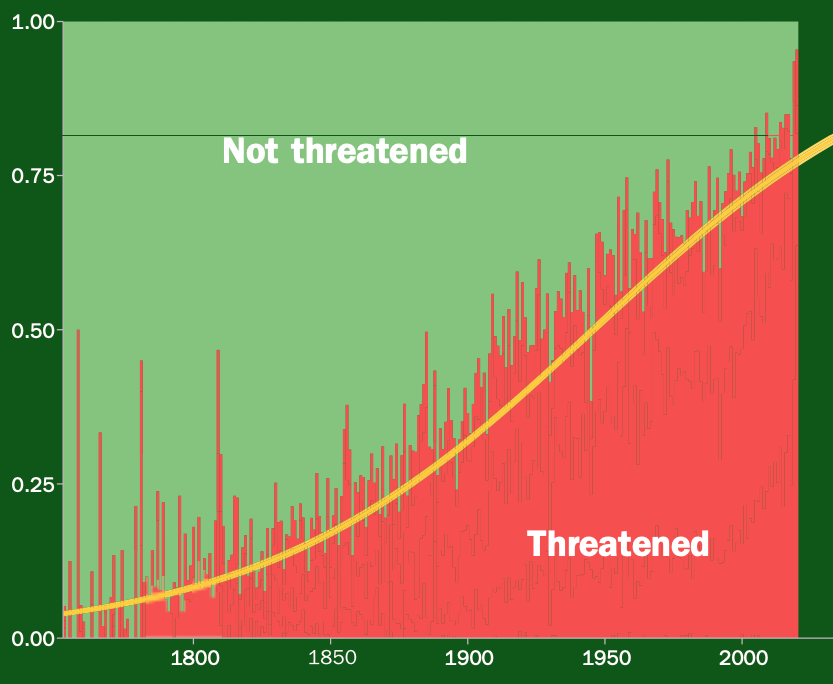

The findings, outlined in the chart below, show that the later a species is formally identified and described by science, the higher chance it has of being deemed at risk.

Based on this finding, Kew scientists are calling for all newly described plant species to be “presumed threatened with extinction unless proven otherwise”, the report says.

The IUCN extinction criteria used does not give a timeframe estimate for when an extinction is likely to occur.

Understanding extinction is “critical to conserving biodiversity”, the report adds. But unless formal naming accelerates, it says, “we are in danger of losing species before they have been described”.

This would mean “losing all of the potential that that species has”, Dr Matilda Brown, a conservation science analyst at Kew, said at the launch of the report.

The director of science at Kew, Prof Alexandre Antonelli, says that unless there is a “real shift” in trends, the number of unknown species at risk “will be even higher” in future.

He tells Carbon Brief that this would result in “basically all the new species that are found being threatened”. He adds:

“It just takes time to formally assess species and that timeline could be fatal basically because most resources for conservation are not allocated until you have a formal threat categorisation of a species. Therefore, we think that it’s very sensible to recommend all [undescribed] species be treated as such.”

The number of threatened plants has risen “shockingly” in recent years, says Dr Martin Cheek, a senior research leader at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. In the report, he writes:

“When I started out as a taxonomist 30 years ago, you wouldn’t really even consider that a species you were publishing might go extinct; you just assumed it was going to still be around in the wild.

“Now, you might work out that you have [a] new species and go and look for its natural habitat only to not find any at all.”

2. Climate change is having ‘detrimental’ impacts on fungi

The main threat to both plant and fungi species is habitat loss and land-use change in the form of forestry, agriculture or residential and commercial development.

For example, timber production can reduce areas of older, natural forest, which can leave behind less deadwood and fewer old trees for fungi to populate.

Climate change is having “detrimental” impacts on fungi in different ways, the report says, with changes in temperature and moisture levels having a direct impact.

There have already been widespread plant and animal population extinctions caused by climate change, detected in almost half of 976 species examined, according to the UN’s authority on climate science, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The IPCC also says that one in 10 species is likely to face a “very high” risk of extinction at 2C of global warming, the upper limit of the Paris Agreement. This rises to 12% at 3C, 13% at 4C and 15% at 5C.

Fungal diversity depends on plants, so any climate-related habitat change that negatively impacts plants “in turn affects their co-existing fungi”, the report says.

Antonelli explains that there is a certain “shortage of knowledge” on the specific role of climate change in extinction risks for many plant and fungi species.

However, climate change is “tremendously” significant to extinction risks and its impact is “expected to increase over time” to possibly become the biggest risk in future, Antonelli adds. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Every time a species is assessed, the experts assessing it will determine whether climate change is or is not a contributing factor to its threat.

“In many cases, the real acute changes we are seeing are in terms of habitat degradation and deforestation, or destruction of grasslands. But it’s harder to really know or predict how much climate change is going to affect particular species because there has not been [as much] experimental research testing that.”

He says more research is needed to test the effects of drought, heatwaves, extreme weather events and gradually increasing mean temperatures on species’ “fertility or seed prediction or dispersal”.

There are other ways climate change can affect extinction risks for plants and fungi, such as by driving increased droughts or reducing resilience to new diseases, Antonelli notes:

“Even though pathogens and disease are a separate category in the threat assessments, those two could be interplaying.”

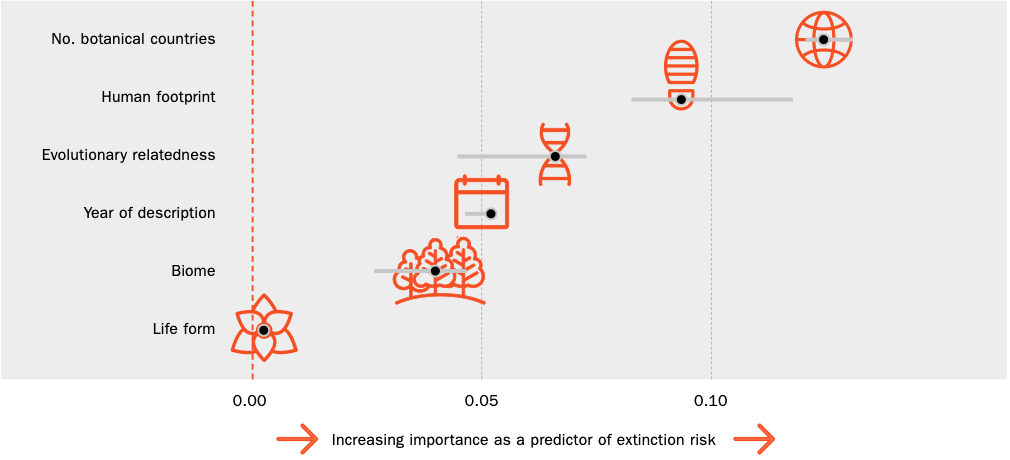

The graphic below shows the different predictors of plant extinction risk and their significance in risk predictions. The main risk identified in the report is the number of “botanical countries” in which a species is present – an area used to define a plant’s distribution that may diverge from official country lines. This is because their area of inhabitance is already limited to begin with.

Brown says that “people aren’t taking extinction seriously enough”. She adds in the report:

“We wanted to show that extinction is being underrated and underestimated, and that we need to do something about it.”

Antonelli says that there are other climate benefits to increasing knowledge of plants and fungi, including understanding the different carbon storage abilities of species.

A recent study estimated that fungi attached to plant roots each year remove 13bn tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere, the equivalent of around a third of annual fossil-fuel emissions.

The authors noted that this estimate is based on the best available evidence, but should still be “interpreted with caution”.

3. Plants are currently going extinct 500 times faster than before humans existed

On average, more than two plant species have gone extinct each year for the past 250 years, according to a 2019 study cited in the report.

This is 500 times faster than the “background extinction rate” – the rate of extinctions absent from human interference. Plants that were scientifically described more recently are becoming extinct twice as fast as those described before 1900, the study adds.

Nearly 600 plant species have been driven to extinction in modern times – but almost as many have been rediscovered after being declared extinct.

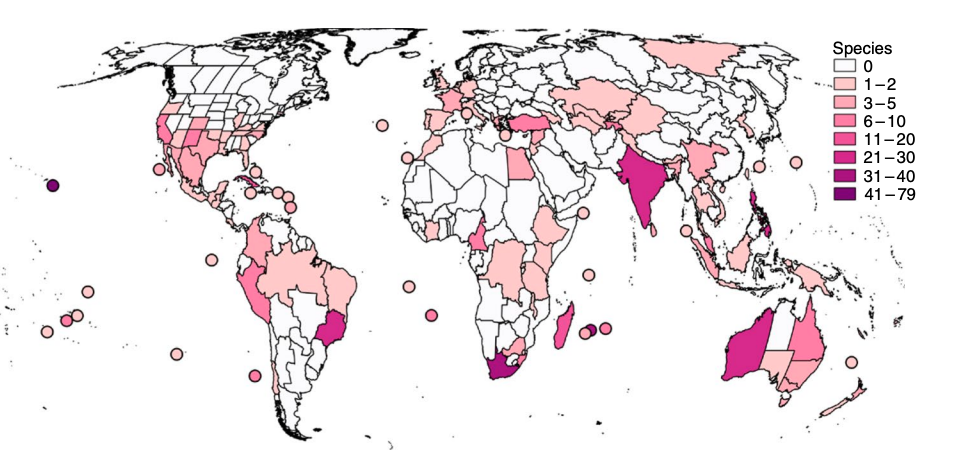

The map below shows the geographic distribution of recorded plant extinctions that have occurred in recent centuries. Darker colours indicate a higher number of extinctions. The study notes that the pattern is “strikingly similar” to that of animal extinctions, with a disproportionate number of extinctions occurring on islands.

Nearly every recorded plant species that has gone extinct was found only in a single area or region.

The Kew report says that these “endemic” plant species may be “particularly affected by habitat destruction and climate change” as their ranges are small to begin with.

Just 10 nations host more than half (55%) of endemic plant species, the report adds, with Brazil, Australia and China hosting the highest number.

The report says this is a significant point for countries to understand the “extent to which the unique species they host are threatened with extinction” and to include this in their conservation strategies.

Other studies have put the modern extinction rate closer to 1,000 times faster than pre-human extinction rates. And still others predict that this could rise to 10,000 times faster, if all species that are currently “threatened” go extinct within the next century.

Brown notes that a lot of human-caused changes to biodiversity patterns are “leading to homogenisation”. She adds in the report:

“By carting species around the world and losing unique threatened species, we are making regions that were once really distinct much more similar, so we are blurring the edges of our global biogeographical regions.”

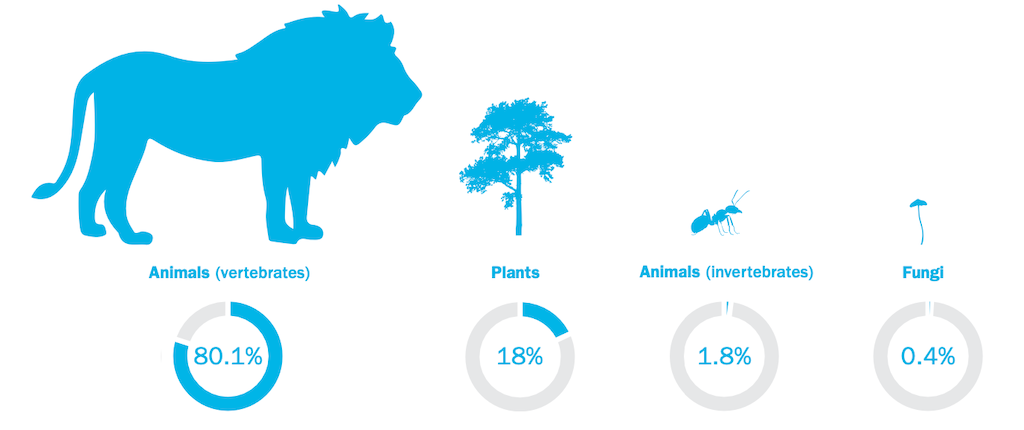

4. Scientists have assessed the risk of extinction for less than 1% of known fungi species

“Fungal interactions are absolutely essential to ecosystem health,” Antonelli tells Carbon Brief.

Around 155,000 fungi species have been documented in scientific literature. But, of these, only 625 known fungi species have had their extinction threat assessed by the IUCN Red List – just 0.4%.

Over the past two decades, a concerted effort by scientists and hobbyists has seen the number of fungi species evaluated on the IUCN red list go from just two in 2003 to a predicted 1,000 by the end of this year.

The report estimates that there are 2.5m fungi species around the world, meaning only 0.02% have had their global extinction threat level assessed.

Bridging this gap, the report says, is “challenging but possible”.

More than 20,000 fungi and lichen species have had their extinction threat level assessed nationally – with a strong bias towards assessments in the global north. These national-level “red lists” can help policymakers identify priority areas for conservation and guide decision-making around land management.

The image below shows the number of IUCN red-list assessments for different groups of organisms. It shows that fungi are by far the least assessed organism.

The report calls for increased engagement with communities and citizen science projects to help document the as-yet-unnamed species.

Dr Kiran Dhanjal-Adams, postdoctoral researcher at Kew, notes in the report that, although many species have not been formally described by science, they “are, in fact, well known by Indigenous communities”. He says:

“Species extinctions and cultural extinctions are inextricably interlinked. With the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework [GBF] highlighting the importance of Indigenous and local communities in conservation, we have the basis for strengthening partnerships and increasing our capacity to describe species in a way that can help raise conservation interest and funds to support local communities, as well as shedding light on ‘darkspots’.”

The new report identifies 32 plant “darkspots” – areas estimated to be the most lacking in information on plant diversity and distribution. These include Colombia and New Guinea.

5. Almost half of flowering plant species are under threat

The Kew report says that 45% of all known flowering plant species are potentially threatened with extinction.

This figure and others outline the “scale” of the “biodiversity crisis”, Antonelli tells Carbon Brief, adding:

“I am absolutely struck. I think it’s a disaster and it’s a really extremely serious situation. But, that said, we do know there are solutions and we are absolutely confident that we can turn this around.”

Scientists used a dataset of more than 53,000 red-listed species to also train a model to predict extinction risks of all the unassessed flowering plant species, the report explains.

Their findings indicate that “epiphytes” – plants that grow on other plants – are the “most threatened plant form”.

The report helps to address some “basic questions” about biodiversity and furthering understanding of species numbers, locations, threats and support needs, Antonelli says.

This information is “fundamental” to meeting the global goals and targets aimed to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by the end of this decade. These were agreed between almost every country in the world at the COP15 biodiversity summit last year. Antonelli tells Carbon Brief:

Your support matters…“All species are important and invaluable to ecosystems, but I think there’s a real danger of not being able to create the baseline information about plants on time for those priorities for conservation and restoration to be designed.”

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.