The Slow Death and Stunning Rebirth of a Great American Newspaper

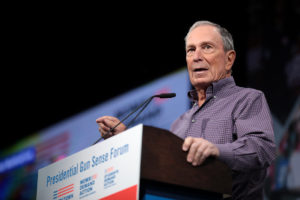

After years of venal, incompetent management, the Los Angeles Times has renewed its commitment to journalists and readers alike. Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong purchased the Los Angeles Times and The San Diego Union-Tribune earlier this year. (Evan Vucci / AP)

Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong purchased the Los Angeles Times and The San Diego Union-Tribune earlier this year. (Evan Vucci / AP)

Part one of a two-part series.

Donald Trump’s presidency poses an existential threat to a free press, but the dangers are manifold. Take the venerable Los Angeles Times, where a band of dedicated journalists is working tirelessly to save the publication from ruin after years of incompetent and venal management.

As newspapers continue to fold, we’ve grown perilously short on local coverage. The dissolution of a paper as big as the Times would be a grievous blow, not just for the region, but the country as a whole. Without it, Southern Californians would be left to the scattershot reporting of cable news and a multitude of Internet outlets focused almost exclusively on Donald Trump and often peddling erroneous, partisan slants.

It will take more than a dedicated staff to resuscitate the Times. The new owner, Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, will have to spend a portion of his billions. In addition, entrepreneurial skill will be needed to figure out how to turn a profit in a newspaper industry gone digital. Finally, the frayed connection between the Times and its readers must be mended.

First, a look at the changes that have been implemented already:

- Perhaps the strongest sign that Soon-Shiong is willing to improve the paper is the large number of people he is hiring after staff dwindled from 1,200 to 400 in the late ’90s. Asian coverage is being strengthened, with two reporters headed to Singapore and another to Beijing. The Beirut bureau is reopening, and another bureau will be opening in Western Europe.

- Local and California coverage will increase with the addition of more metro reporters, including an investigative journalist and an additional reporter covering the neglected county government. The Seattle bureau will be reopened as well.

- Three beat reporters have been added to the sports staff, which has its own podcast, and a sports editor has been elevated to deputy managing editor.

- Former staffers who departed amid massive cuts to staffing have been rehired.

- Digital resources are being expanded in an effort to improve the perennially lagging website.

- The Washington bureau, scheduled for extinction under previous management, is growing.

- Two new restaurant critics have been hired to write weekly reviews following the death of the esteemed Jonathan Gold.

The latest developments at the Los Angeles Times, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Bettina Boxall told me, are about the “rebirth of a great newspaper. How do you take a great institution butchered by greed and rebuild it?” (She and Times reporter Julie Cart won the Pulitzer in 2009 for their series on combating wildfires in the western United States.)

“I have been here for 31 years,” Boxall added. “I am positive and hopeful. … It truly feels miraculous. It truly does. We’ve hit bottom and we are on our way up. If it doesn’t work, we only have ourselves to blame.”

“The morale of the staff is much better than it was, people are more optimistic,” offered Mitchell Landsberg, the newly named foreign editor who was a star on the metro staff for several years as a writer and reporter.

Sewell Chan, who moved to the Times as an editor from The New York Times, told me he watched “with dismay what has happened in the last decade.” He sees the staff as a source of strength. In joining a media employee union, he said, the Times journalists have shown themselves to be “a very well-organized staff. It has taken upon itself the stewardship of the institution. That excites me … collaboration [is needed] if the turnaround is to succeed.”

Chan also offered praise for the reporters and editors who kept the paper going during the darkest days. “They are a battle-hardened group, very clear-eyed, very sober,” he said. “They’re not expecting to spend a 30-year career in any institution. They are more willing to take risks and to learn from the old-timers.”

Much of the revival effort is coming from the unsung women and men who cover local news: the metro staff, the largest group of reporters and editors on the paper and, in my mind, the heart and soul of the institution. (Full disclosure: I was a member for most of the 31 years I spent on the Times, as city-side reporter, political reporter, bureau chief, columnist and city editor. In the last job, I led the staff through one of its most turbulent periods.)

The media industry is evolving in real time. Old methods of gathering the news are being jettisoned in favor of automated tools that favor the young and technically adept. Robots write rudimentary stories and conduct research that was once the exclusive domain of human beings. Algorithms have superseded editors who once used their gut feelings to choose a story to feature. Reporters still dig deeply into stories, but they must also work at high speed, churning out multiple pieces a day—in words, videos, photographs and graphic charts. Layoffs, retirements and resignations have left newsrooms skewed incredibly young and relatively inexperienced.

“[Before], there were so many veterans, it was so collegial,” said city editor Hector Becerra. “Everywhere you turned there was someone you could learn from.”

Despite these myriad improvements, pay remains static. Meanwhile, employees’ long battle against previous management has left some traumatized. For the first time in the paper’s history, editorial voted overwhelmingly to join the NewsGuild union, and a nine-person negotiating committee is battling it out with management twice per week in sessions that sometimes last nine hours.

According to NewsGuild, the average salary for women at the Times is $87,565 and $101,898 for men. People of color earn $85,622 annually, while white reporters make in excess of $100,000. Pay is considerably lower for the inexperienced women and men hired under the Metpro program to bolster diversity on staff. The average Metpro pay is $44,200 a year.

Matt Pearce, one of the leaders of the unionization efforts, said, “We need a strong contract … and soon.” If not, he warned, journalists will move on to publications already recruiting Times staff members: “People must see an improvement in conditions.”

Several weeks after Soon-Shiong took over the paper, and its smaller sister publication, the San Diego Union, I visited the paper’s new headquarters in El Segundo for a progress report.

I drove into the paper’s parking lot, stopping at security and finding a place among the many cars. I walked toward the seven-story cracker-box building. But for the Los Angeles Times signs across the top floor, I could have been entering any tech headquarters on West Imperial Highway on the southern edge of Los Angeles International Airport. The area has been touted as Silicon Beach, but its developers have scorned the futuristic architecture of its progenitor in Northern California.

The office felt sterile compared with the old Times building that used to house the paper. That building, a 1935 art deco structure in downtown Los Angeles, featured a large globe in its lobby, a symbol of the paper’s aspirations, along with framed pictures of the Times’ most memorable stories. The old newsroom, on the third floor, was so big that I thought I would never find my way around it, much less hold my own with the talented journalists who worked there.

Soon-Shiong believes the move was a matter of expedience. The previous owners had sold the previous building to a developer who was raising the rent exorbitantly. But many in the community felt there was a dangerous symbolism in the move from urban Los Angeles, across the street from City Hall, to a distant suburb with a population of just under 17,000, mostly white.

On my visit to the new site I felt conflicted as I shuffled through the airport-level security in the lobby. Hillary Manning, vice president for communications, escorted me to the office of the executive editor, Norman Pearlstine, and we passed a number of vacant desks. Long gone was the mess and the quirk of the newsroom downtown.

Pearlstine, 76, has been tasked with rebuilding the Times after a career that began as a reporter for The Wall Street Journal. (He later worked as an editor at the Journal and Time.) Our paths had crossed over the years and I had found him to be smart and likeable. His varied and successful tenures have given him a confidence that makes him easy to interview. And it’s clear he has the experience for the difficult task at hand.

As someone who came up through the ranks, Pearlstine seems to understand that he needs the loyalty of his staff to succeed. A journalist is an odd duck: suspicious of authority, yet engaged in a trade with a hierarchical structure; willing to take orders, but occasionally rebelling when pushed too far. A Times staff revolt had led to the ouster of the paper’s two previous editors and the formation of the union. Without his staff’s backing, rebuilding the Times would be all but impossible.

When Pearlstine and I first started in journalism, pay was low, bosses rough and futures less than promising. Although my parents offered their support, friends were doubtful and my soon-to-be father-in-law openly hostile.

“I’m sure that when you came up, your relatives did not jump with joy that you were not going to law school,” I told him.

“I went to law school, but I didn’t practice with my father, and my mother didn’t speak to me for five years after that,” he replied. “The fact that it was The Wall Street Journal finally brought her around because my father’s clients were subscribers to it. She thought perhaps it was an exception, but she was appalled at the idea that I would not practice law.”

Perhaps because Pearlstine began his career in the years before Watergate and Woodward and Bernstein, when journalism was distinctly unglamorous, he views the effort to rebuild the Times in a realistic way. Whereas previous management wanted to rip up the place and slash the staff down to practically nothing, Pearlstine appears to value journalists.

“When I talk to people who have been here five years and are still making $60,000, they are very unhappy about pay. They very much expect management to address those issues,” he said. “But when you ask them if they love the paper, they love a lot of the people they work with here, they love the complexity of the local story that is Los Angeles, and they would prefer to stay here if they can make a living wage. Now you can’t generalize—it’s not everybody—but I have talked to a fair number to encourage them to hang in through the negotiation. But there is a lot of pressure. It is not a cheap place to live.”

The origins of their discontent date back to the sale of Times Mirror Co. by the company’s longtime owners, the Chandler family. After its more conservative faction seized control and ousted revered Publisher Otis Chandler, the family sold the company to the Chicago Tribune company. By then, print newspapers had begun to falter, hemorrhaging advertising to internet companies beyond the comprehension of old-time publishers. The hidebound Tribune stumbled. The top editors it had hired to run the Times, Editor John Carroll and Managing Editor Dean Baquet, fought hard for the paper and its staff, continuing its award-winning tradition. But when staffers protested the Chicago-ordered cuts, Carroll was forced out, followed by Baquet, who had succeeded him. Carroll died in 2015; Baquet is now executive editor of the New York Times. Wave after wave of incompetent management followed, each laying the paper lower than their predecessors had.

On Aug. 21, 2017, the latest management team was fired by the Tribune leadership, which had renamed the company Tronc. Editor and Publisher Davan Maharaj was dumped, as was Managing Editor Marc Duvoison, and his wife, investigative reporter and author Jill Leovy. Deputy editor for digital Megan Garvey and Matt Doig, the assistant managing editor for investigations, were axed as well. Poetically, a solar eclipse engulfed the country that day, darkening skylines from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

“We came into work, the eclipse started and by the end of the eclipse everyone was gone,” recalled Scott Kraft, who, in the turbulent days that followed, found himself unexpectedly in charge.

A modest person who speaks softly but commands respect, Kraft now serves as the paper’s managing editor after more than a decade as a foreign correspondent in cities ranging from Paris to Nairobi.

“What happened?” I asked. “Did they tell you you’re in charge of the paper?”

“Not really,” he said. “Jim Kirk was interim editor, but he was a short-timer who didn’t know the staff or Southern California. I like him a lot—and his journalistic sensibilities—but he was a caretaker, couldn’t make any decisions.”

Without anyone telling him, Kraft effectively became the paper’s editor.

“I was the most senior person left with news responsibilities, and so I had to do that,” he said. “But also I thought it was really important at the time to make sure that the people in the newsroom felt that they had someone they could come to with their concerns. And even if in many cases I didn’t have the authority to address some of those concerns, I think it was good. I think I became a person they felt that they could come to, they came to vent, to express concern and also on journalistic questions that come up day to day. People would often come into my office and say, ‘I don’t know who else to go to with this, can you help me?’ And I would.”

Kraft had to keep the staff together. He urged them to stay “if you like what you doing and you have colleagues who are collegial.” Appealing to reporters’ pride and taste for combat, he told them, “We are here on a pirate ship covering a great city, a great state.”

Tronc would replace Editor Maharaj with someone far worse, Lewis D’Vorkin, who, as editor of Forbes, had installed a system of filling his magazines with the work of unpaid contributors. In journalistic circles, he had earned the nickname “The Prince of Darkness.” Reporters on the Times staff would later uncover his plans to slash the metro staff.

“It was worse than Trump,” Kraft said.

In an interview with Jessica Yellin of the USC Annenberg School of Journalism at the Pacific Council on International Policy, Publisher Soon-Shiong acknowledged the toll those years had taken on the staff. “The first thing I had to do was ensure stability,” he said. “When I went to the newsroom, it really felt like it was a beaten child. They had been through this terrible trauma for years and years and years, and I wanted to assure the newsroom, which is the heart of the organization, that not only were they important, they were valued.”

The Washington bureau, once a storied institution, had shrunk to 11 members, and Tronc appeared ready to close it. (The bureau was a separate entity owned by the Times and other Tronc papers.) “It was a bad time,” David Lauter, the bureau chief, said. “Everyone in the room was looking for other jobs. A couple had gone. At any moment, there was a feeling that they (Tronc) could call up and say, ‘Friday is your last day.’ I worried about it. If it happens, where can I place this person or that person.”

“What about yourself?” I inquired.

“I’m not old enough to retire,” he said. “That was a concern. I worried about it.”

Soon-Shiong has saved the bureau. “Several days after (the purchase was announced) I got a call from Patrick,” Lauter said. “I met him at his hotel. He said the Washington bureau would be included in his purchase. He bought this separate subsidiary. He took on the financial burden and he made the point that he had done it. It was very encouraging to hear.”

“We were able to right away fill vacancies and create new jobs,” Lauter continued. Eventually, he was authorized to hire full-time immigration and environmental reporters. The size of the bureau has increased from 11 to 17 members, and there are hopes that number can climb to 20.

It was late in the day when I finished my interviews at the paper’s new headquarters. “What do you think?” one of the editors asked as I headed out. “Looks good,” I quipped.

Despite the myriad challenges that await, I meant what I said.

To read part two, examining Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong’s vision for the Los Angeles Times and the kinds of challenges threatening the paper’s revival, click here.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.