The Red, White and Blue Notes

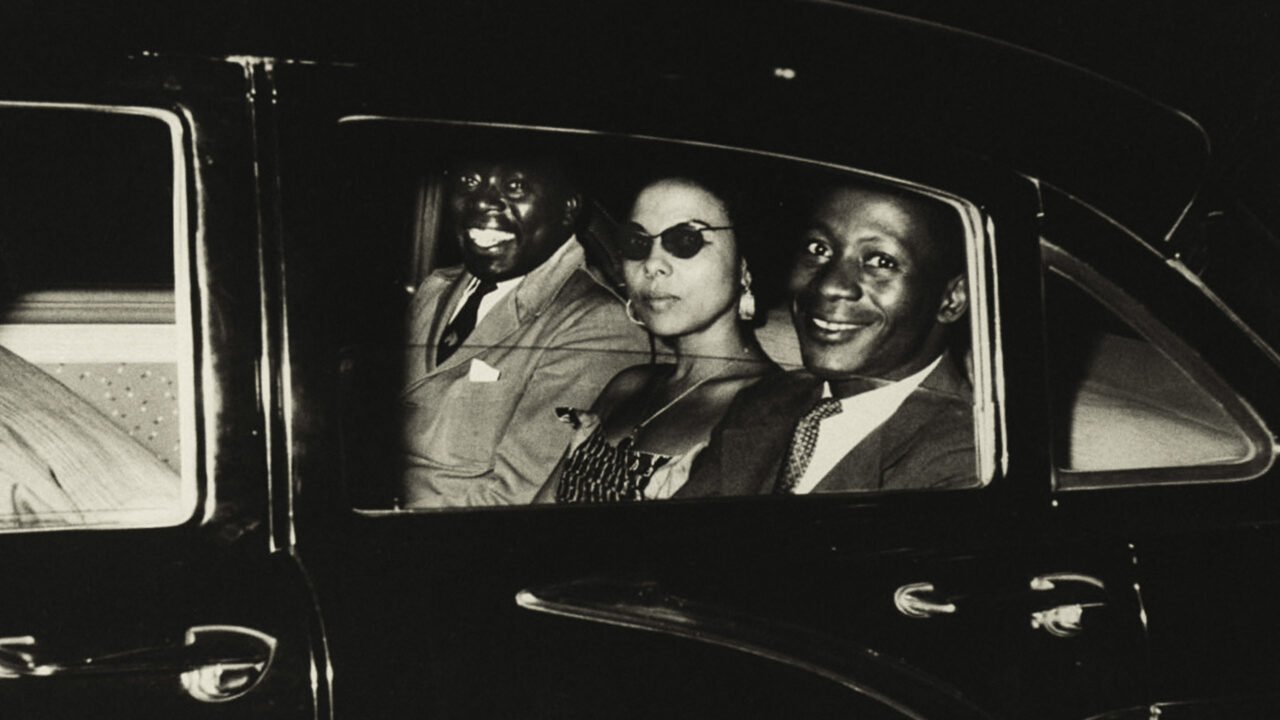

“Soundtrack to a Coup d'État” takes an impressionistic approach to the weaponization of American music during the Cold War. Andrée Blouin and Patrice Lumumba appear in Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat by Johan Grimonprez.. Courtesy of Sundance Institute. Photo by Terence Spencer.

Andrée Blouin and Patrice Lumumba appear in Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat by Johan Grimonprez.. Courtesy of Sundance Institute. Photo by Terence Spencer.

“Soundtrack to a Coup d’État” premieres online at The Sundance Film Festival on Jan. 25 (7:00 AM PST) and Jan. 28 (10:55 PM PST). Tickets to the limited online screening are available on the festival website.

In “Soundtrack to a Coup d’État,” Belgian director Johan Grimonprez has created a visual collage with New Media flare. An impressionistic tale of the CIA’s attempts to influence global public opinion during the 1950s and ’60s by deploying “jazz ambassadors” in Africa and across the Global South, the two-and-a-half-hour Sundance documentary is an unlikely pairing of subject and form that joins Dziga Vertov’s “Man with a Movie Camera” (1929) and Orson Welles’ “F For Fake” (1973) in the grand — though today seldom practiced — cinematic tradition of the visual essay.

“Soundtrack to a Coup d’État” pivots largely around Congo’s independence in 1960 and Patrice Lumumba, the nation’s first prime minister who was overthrown the following year with support from the U.S., Belgium and France. Today, the country is a key supplier of cobalt to the West and a hotbed of corporate slavery, which the film establishes in the style of a YouTube video, with pointed arguments about Congolese Corporatocracy interspersed with ads for Tesla and Apple products, two of the companies accused of using child labor in the region.

Before landing on its contemporary narrative, the film hops and skips through time to various mid-century political press conferences, interviews with intelligence agents, international musical tours and U.N. speeches. In doing so, it observes the era’s rapidly-shifting political climate and recreates the postwar years when dozens of nations across Africa, Asia and Latin America threw off the shackles of colonialism and stood together in the face of competing influence-peddling by Washington and Moscow. The film highlights the revered political voices that spoke for these young countries. Leaders like Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser feature heavily in the film, as does the 1961 U.N. Summit where Nikita Khrushchev famously banged his shoe on the table while railing against the overthrow of Lumumba and America’s racial inequities. Less remembered today is the fact that the same conference was crashed by jazz musicians Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach in protest of Belgium’s role in Lumumba’s overthrow. By contrasting the percussion and images of famous American musicians, Grimonprez suggests that Khrushchev’s inelegant pounding perhaps exists on the same spectrum as Washington’s use of jazz as a propaganda tool.

The movie unabashedly makes the case for America’s key musical export as a force for good.

Music was rarely a tool of diplomacy until American intelligence agencies began sending the likes of Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and Duke Ellington abroad to whitewash America’s cultural reputation. While “Soundtrack to a Coup d’État” is critical of this political program, it is as much a celebration of jazz and blues as a story of their exploitation. The movie unabashedly makes the case for America’s key musical export as a force for good, delving into the rebellious impetus behind the work of numerous Black musical artists by transcribing both their lyrics and anti-imperial viewpoints more generally. When Armstrong visits the Congo during its civil war, or when Nina Simone is sent to Nigeria (unbeknownst to her, by the CIA), Grimonprez presents the unsavory implications of these missions as well as the wider context of their bodies of work and their place in the American and global public consciousness. At their core, these whitewashing programs represented Black artistic rebellion in the U.S. being weaponized to quash Black political rebellion in Africa, a complication captured by the film’s violent oscillations between footage and on-screen quotes relating to both sides of the neo-colonial project.

“Soundtrack” is meticulously researched and detailed in its use of archival footage, drawing from numerous memoirs, interviews, newsreels and live musical performances. Despite its frequent use of on-screen text, the movie is instinctive and impressionistic in its storytelling, and aims to convey its political purview through emotion as much as logic. Grimonprez’s montage approach sets rapid-fire quotes and headlines to the movie’s era-appropriate jazz soundtrack, a testament to the artistry always at play beneath (or in spite of) the political context upon which the art is applied.

History, like music, continues to resonate, and Grimonprez and editor Rik Chaubet harness their echoes into a propulsive audiovisual experience. Despite a breadth of factual detail and archival reference, “Soundtrack to a Coup d’État” feels loose, snappy, free-flowing, almost improvised. A cinematic translation of jazz.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.