The Persistence of Marcus Whitman’s Myth in the West

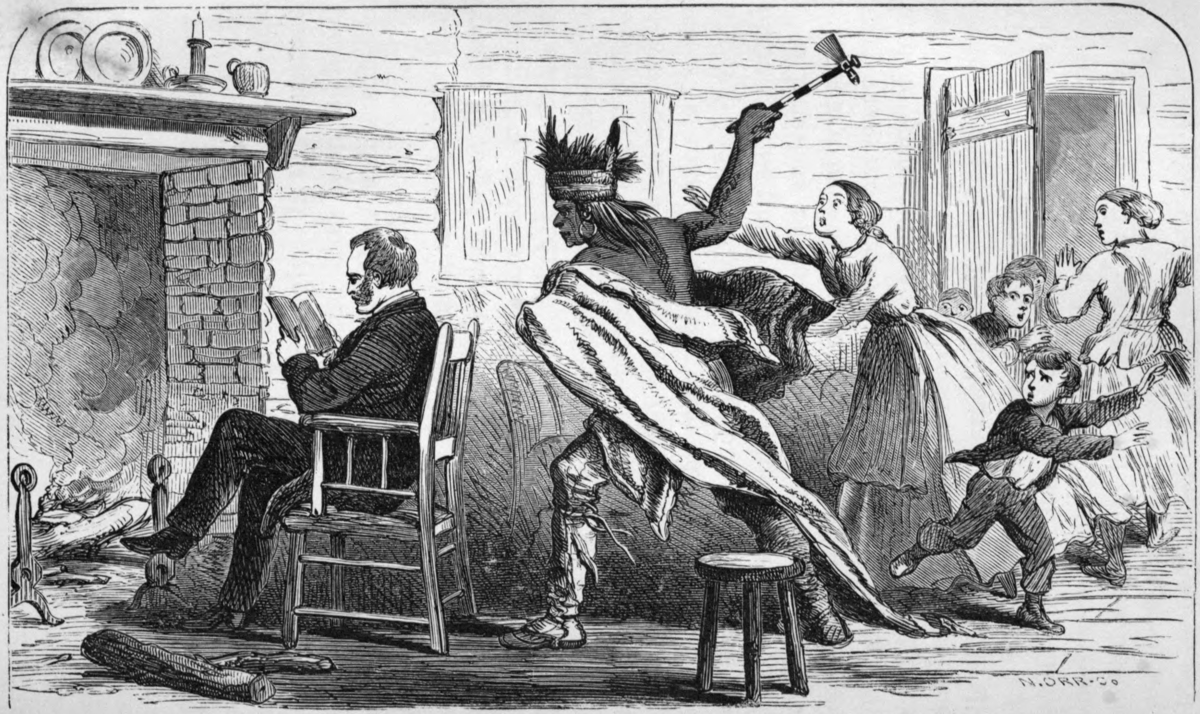

In "Murder at the Mission," Blaine Harden examines a great American lie bolstered by the collective imagination of a populace raised on Manifest Destiny. Dramatic depiction of the Whitman "massacre" from "Eleven Years in the Rocky Mountains and a Life on the Frontier" by Frances Fuller Victor (1877).

Dramatic depiction of the Whitman "massacre" from "Eleven Years in the Rocky Mountains and a Life on the Frontier" by Frances Fuller Victor (1877).

“The Whitman lie is a timeless reminder that in America a good story has an insidious way of trumping a true one, especially if that story confirms our virtue, congratulates our pluck, and enshrines our status as God’s chosen people.”—Blaine Harden, Murder at the Mission

As the result of a good story, the Reverend Marcus Whitman and his wife Narcissa became perhaps the most revered pioneer couple in the history of America’s westward expansion.

Six decades ago, as a student in Spokane, Washington, I learned of the Whitmans in a course on our state history, a requirement in Washington schools.

In our textbooks and lectures, the Whitman couple was virtually deified as benevolent Christian pioneers who offered Indians salvation as they brought civilization to their backward flock. At the same time, they encouraged others from the East to join them where land was plentiful and open for the taking. And Reverend Whitman was celebrated as an American patriot who saved for America the territory that became the states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho from a plot hatched by the British with Catholic and Native co-conspirators.

We also learned of the Whitman massacre: the shocking and gruesome 1847 murders of the gracious Whitmans and eleven other white people by renegade Cayuse Indians in an unprovoked attack at their mission near present day Walla Walla. The massacre became a flashpoint in the history of the West.

It turns out that the Whitman story we were taught decades ago was rife with lies, as acclaimed journalist and author Blaine Harden reveals in his lively recent book, a masterwork of historical detection, Murder at the Mission: A Frontier Killing, Its Legacy of Lies, and the Taking of the West (Viking).

Mr. Harden learned the same version of the Whitman tale that I did in the early sixties as a fifth-grade student in Moses Lake, Washington. In recent years, he decided to meticulously investigate the Whitman legend and set forth an accurate historical account of the amazing story we learned in school.

Murder at the Mission presents a nuanced and complicated history of settler colonialism, racism, greed, righteousness, and mythmaking. Based on exhaustive research, including recent interviews with members of the Cayuse tribe, Mr. Harden traces the actual journey of the Whitmans and events leading to their deaths. He also reveals the origins of the Whitman hoax and how the lies about the Whitmans were spread after the massacre, notably by an embittered fellow missionary, the Reverend Henry Spalding.

With the help of religious, business and political leaders invested in a story to justify the evils of Manifest Destiny and westward expansion, Spalding’s exalted tale of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman was endorsed by major publications and the Congress and was shared in textbooks. The lie was so effectively spread that, by the end of the nineteenth century, Marcus Whitman was seen as one of the most significant men in our nation’s history.

Mr. Harden dissects and analyzes every aspect of the fabulous Whitman tale as he debunks the lie with primary sources and other evidence. The book also brings to life the predicament of the Cayuse people and other Native Americans where the Whitmans settled, as epidemics ravaged the tribes and a flood of white settlers pushed them from their traditional lands. And Mr. Harden places the Whitman lore in historical context by examining parallel accounts of the dispossession and extermination of other Native Americans in the conquest of the West.

Murder at the Mission exposes the lies at the center of a foundational American myth and examines how a false story enthralled a public weaned on Manifest Destiny and eager for validation of its rapacious conquest and intolerance while ignoring evidence-based history and countervailing arguments. As we continue to deal with the disinformation, potent political lies, genocidal conflicts, and systemic racism, Mr. Harden’s re-assessment of this history is powerfully resonant now.

As we continue to deal with the disinformation, potent political lies, genocidal conflicts, and systemic racism, Mr. Harden’s re-assessment of this history is powerfully resonant now.

Blaine Harden is an award-winning journalist who served as The Washington Post’s bureau chief in East Asia and Africa, as a local and national correspondent for The New York Times, and as a writer for the Times Magazine. He was also Post bureau chief in Warsaw, during the collapse of Communism and the breakup of Yugoslavia (1989-1993), and in Nairobi, where he covered sub-Saharan Africa (1985-1989). His other books include The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot; King of Spies: The Dark Reign of America’s Spymaster in Korea; Africa: Dispatches from a Fragile Continent; A River Lost: The Life and Death of the Columbia; and Escape from Camp 14. Africa won a Pen American Center citation for first book of non-fiction. Escape From Camp 14 won the 2112 Grand Prix de la Biographie Politique, a French literary award and enjoyed several weeks on various New York Times bestseller lists and was an international bestseller published in 28 languages.

Mr. Harden’s journalism awards include the Ernie Pyle Award for coverage of the siege of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War; the American Society of Newspaper Editors Award for Nondeadline Writing (stories about Africa); and the Livingston Award for International Reporting (stories about Africa). He has contributed to The Economist, PBS Frontline, Foreign Policy, and more. He lives in Seattle with his family.

Mr. Harden sat down at a Seattle café and generously discussed his work and his recent book Murder at the Mission.

Robin Lindley: Congratulations Mr. Harden on your revelatory work on the myth of Marcus Whitman in your new book, Murder at the Mission. Before we get to the book, could you talk about your background as a globetrotting foreign correspondent and author of several previous books?

Blaine Harden: I grew up in Moses Lake, a little town in eastern Washington, and in Aberdeen, which is on the coast. My father was a construction welder and we moved when he found jobs or when he lost jobs. And so, we moved from Moses Lake to Aberdeen and back to Moses Lake. My father’s work was dependent on the construction of dams on the Columbia River and on other federal spending in the Columbia Basin. His wages as a union welder catapulted him and his family from working class poor to middle class. So, when I graduated from high school, there was enough money for me to go to a private college. I went to Gonzaga University in Spokane and then to graduate school at Syracuse.

When I was at Syracuse, I had the great good fortune of having a visiting professor who was the managing editor of the Washington Post, Howard Simons. I made his course my full-time job and ignored every other class. He offered me a job. I worked for one year at the Trenton (N.J.) Times, a farm-club paper then owned by the Washington Post.

When I was 25, I was at the Washington Post. I worked there locally for about five years. Then I worked from abroad, which is something I always wanted to do when I was at college. I was a philosophy major, and I read Hume who wrote that you could only know what you see in front of you, what you experience with your senses. I had this narcissistic view that the world didn’t exist unless I saw it.

I went to Africa for the Post and was there for five years. Then I was in Eastern Europe and the Balkans for three years during the collapse of Communism and the collapse of Yugoslavia. When that was over, I’d been abroad for eight years, and I was a little tired of it. I wanted to write another book. I’d already written one about Africa.

I came back and to the Northwest and wrote a book about the rivers and the dams and the natural resource wars that were going on in the Pacific Northwest over salmon and the proper use of the Columbia River.

I did that book, and then went back to Washington, D.C., and then to Japan in 2007. I came back to the Northwest in 2010 when I left the newspaper business and wrote three books about North Korea. I’d been in Eastern Europe and then the Far East. These books sort of fell together, one after another.

Robin Lindley: And then you focused on the Whitman story?

Blaine Harden: Yes. Then I was looking for another project. When I was in elementary school in Moses Lake, there was a school play about Marcus Whitman and I played a role. For some reason I remembered that story, and I just started investigating Marcus Whitman. Did he really save the Pacific Northwest from the British?

I went to the University of Washington and spent a couple weeks reading the incredibly voluminous literature about Whitman. It didn’t take long to understand that everything I had been taught in school was nonsense.

The history we learned was a lie, and it was a deliberate lie, one that had been debunked in 1900 by scholars at Yale and in Chicago. But the people of the Pacific Northwest, despite all evidence to the contrary, had clung to a story that was baloney. That’s what hooked me. I thought this could be a really good book about the power of a lie in America. It was the kind of lie that makes Americans feel good about themselves.

The Whitman lie was perfect for a nation that thinks of itself as extra special. It was action-packed, hero-driven, sanctified by God. It also made Americans feel good about taking land away from Indians.

Robin Lindley: With the Whitman story, many people might ask first wasn’t there really a massacre in 1847? And didn’t Indians attack the Whitmans and kill them and other white settlers?

Blaine Harden: Right. The story of the Whitman massacre is true.

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman came out to the Pacific Northwest in 1836. They were part of the first group of missionaries to settle in the Columbia River Basin. They were there for eleven years, during which time they failed as missionaries. Marcus and Narcissa converted only two people in eleven years. They also infuriated their Cayuse hosts, who frequently asked them to move on, and they refused. The Cayuse asked them to pay rent, and they refused. The Cayuse also noticed that when epidemics occurred, measles in particular, white people would get sick, but they wouldn’t die. Members of the Cayuse and the Nez Perce tribes, however, would die in terrifying numbers. They had no immunity to diseases imported by whites.

Years of bitterness between the missionaries and the tribes culminated with an especially severe measles epidemic, which for many complicated reasons the Cayuse blamed on Marcus Whitman and his wife. So, they murdered the Whitmans along with eleven other white people. The murders were grisly. The Whitmans were cut up, decapitated, stomped into the ground, and buried in a shallow grave.

When word of this atrocity reached the much larger white settlement in the Willamette Valley in what is now western Oregon, people got very upset. They mobilized a militia to punish the Cayuse and sent a delegation to Washington, D.C. They hoped to persuade President Polk and Congress to abrogate a decades-old treaty under which the Oregon County was jointly owned by Britain and the United States. And they succeeded.

The Whitman massacre turned out to be the precipitating event for an official government declaration that Oregon was a territory of the United States. Within a few years, it became the states of Oregon, Washington, and then later Idaho.

Whitman is justifiably famous for getting himself killed in a macabre and sensational way. His murder was indeed the pivot point for the creation of a continental nation that included the Pacific Northwest. But that is where truth ends and lies begin. It would take another two decades after Whitman’s murder for a big whopper to emerge—the claim that Whitman saved Oregon from a British, Catholic and Indian scheme to steal the territory.

Robin Lindley: What was the myth that emerged about Whitman and what was the reality?

Blaine Harden: As I said, the reality was that Whitman and his wife were failed missionaries who antagonized the Cayuse and refused to move. Marcus Whitman was a medical doctor as well as a missionary, and the Cayuse had a long tradition of killing failed medicine men. Marcus Whitman was aware of that tradition and had written about it. He knew he was taking a great risk by working among the Cayuse and he was repeatedly warned that he should leave. He and his wife ignored all the warnings.

When a measles epidemic swept into Cayuse country in 1847, Whitman gave medical treatment to whites and Indians. Most whites survived; most Indians died. In the Cayuse tradition, this meant that Whitman needed killing.

Robin Lindley: And Narcissa Whitman was known for her racist remarks and dislike of the Indigenous people.

Blaine Harden: Narcissa wrote some rather affecting letters about being a missionary and traveling across the country. They were widely read in the East and much appreciated. She became something of a of a darling as a frontierswoman, a missionary icon.

But she never learned to speak the Nez Perce language, which was the lingua franca of the Cayuse. She described them in letters as dirty and flea infected. By the time of her death, she had almost nothing to do with the Cayuse, whom she had come to save. She was teaching white children who arrived on the Oregon Trail.

So that’s the true Whitman story. As for the creation of the Whitman lie, there is another figure in my book who is very important, the Reverend Henry Spalding. He came west with the Whitmans and, strangely enough, he had proposed to Narcissa years before she married Marcus Whitman. He had been turned down and he never forgave her.

Spalding was constantly irritating and speaking ill of the Whitmans during their lifetime. But after their deaths, he decided to cast them as heroes. He claimed that in 1842 Whitman rode a horse by himself back to Washington, D.C., and burst into the White House and persuaded President Tyler to send settlers to the Pacific Northwest—and was thus successful in blocking a British and Indian plot to steal the Northwest away from America.

Robin Lindley: And didn’t Spalding also claim that Catholics were allies of the British in this so-called plot.

Blaine Harden: Yes. Spalding said Catholics were in the plot—and politicians believed him. Spalding was a big bearded, authoritative-looking figure when he traveled back to Washington in 1870. By then, he was pushing 70 himself and was probably the longest-tenured missionary in the Northwest, perhaps in the entire West.

Spalding went to the U.S. Senate with his manifesto, which was a grab bag of lies and insinuations. And the Senate and House bought it hook, line and sinker.

His murder was indeed the pivot point for the creation of a continental nation that included the Pacific Northwest. But that is where truth ends and lies begin.

The manifesto was reprinted as an official U.S. government document. It became a primary source for almost every history book that was printed between 1878 and 1900. Every school kid, every college kid, every church kid in America learned this false story about Marcus Whitman, and it catapulted Whitman from a nobody into a hero of the status of Meriweather Lewis or Sam Houston. That’s according to a survey of eminent thinkers in 1900.

Spalding was spectacularly successful in marketing his lie. What’s important for readers to think about is that this lie appealed to Americans in the same way that lies now appeal to Americans. As I said, it was simple. It was hero driven, action packed, ordained by God, and it sanctified whatever Americans had done. And when they came to the West, white Americans stole the land of the Indians. They knew what they were doing, but to have the taking of the West sanctified by this heroic story made it much more palatable. You could feel much better about yourself if you did it in response to the killing of a heroic man of God who saved the West from a nefarious plot.

Spalding was a smart demagogue who intuited what Americans wanted to hear, and he sold it to them. That may sound like some politicians we know now in our current political discourse, but Spalding got away with it. He died a happy man and was later lauded, even in the 1930s by Franklin Roosevelt as a very effective, heroic missionary. That’s the lie.

Robin Lindley: And you discovered early evidence of those who were skeptics of Spalding’s tale and who debunked his version of the Whitman story.

Blaine Harden: Around 1898, there was a student at the University of Washington who read about Spalding’s Whitman story and didn’t believe it. Then he went to Yale for a graduate degree. While there, he told his professor of history, Edward Gaylord Bourne, about his suspicions of the Whitman story. Bourne was an eminent scholar, a founder of the modern school of history based on primary sources. He didn’t rely on what people were saying happened, but would look at original letters, documents, and other contemporaneous material.

Bourne started to investigate the Whitman story and he soon found irrefutable primary sources showing that Whitman did not save the Pacific Northwest from a plot. Instead, Whitman went to Washington, DC, briefly in 1842 and then went to Boston to save his mission because it was in danger of losing its funding. That was the actual story.

Professor Bourne debunked the Spalding story at a meeting of the American Historical Association in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1900. Most of America’s major newspapers and its academic establishment accepted Bourne’s evidence that Whitman was not a hero and Spalding was a world-class liar. But that didn’t happen in the Pacific Northwest.

Much of the Pacific Northwest continued to believe in the lie. Politicians continued to promote Whitman as the most important individual who ever lived in Washington state. A huge bronze statue of Whitman was chosen to represent Washington State in the U.S. Capitol beginning in 1953, more than half a century after his legend had been debunked. The state legislature in Washington still chose him as the state’s most important historical personage. My book explains why.

Robin Lindley: That Whitman statue to represent Washington State in the Capitol was replaced in the last couple of years. Did your book have anything to do with that?

Blaine Harden: The state legislature made a decision to replace the statue in the month that my book came out, but I can’t claim credit for persuading them to do so. There was just a reassessment going on and my book was part of it [for more on Whitman and his commemoration, see this 2020 essay by Cassandra Tate—ed.].

It’s important to understand why the lie had such legs in the Northwest after it had been debunked nationally. A primary reason was support for the lie from Whitman College. Whitman College was created by a missionary (the Reverend Cushing Eells) who was a peer of Marcus Whitman. It was founded in 1859 and struggled mightily for decades.

Robin Lindley: Didn’t Whitman College begin in Walla Walla as a seminary?

Blaine Harden: Yes. It was a seminary, but by 1882 had become a four-year college for men. By the 1890s, it was in dire financial straits. It couldn’t pay its mortgage. It was losing students. It couldn’t pay its faculty. Presidents of the college kept getting fired. Finally, they hired a young graduate of Williams College who had come west to work as a Congregational pastor in Dayton, Washington, a small town not far from Walla Walla. This young pastor, Stephen B. L. Penrose, joined the board of Whitman College, and very soon thereafter, the college president was fired. Penrose, who was not yet 30, then became youngest college president in America.

Penrose inherited a mess. The college was bleeding students and was on the verge of bankruptcy. Searching for a way to save it, he went into the library at Whitman College and discovered a book (Oregon: The Struggle for Possession, Houghton Mifflin, 1883). It told the amazing but of course false story of Marcus Whitman saving the Pacific Northwest and being killed by Indians for his trouble. Penrose was thunderstruck. He believed he’d found a public-relations bonanza for his college. He boiled the Whitman myth down to a seven-page pamphlet that equated Marcus Whitman with Jesus Christ. The pamphlet said that Whitman, not unlike Christ on the cross, had shed his blood for a noble cause—saving Oregon. The least that Americans could do, Penrose argued in his elegantly written pamphlet, was donate money to rescue the worthy but struggling western college named after the martyred missionary.

Spalding was constantly irritating and speaking ill of the Whitmans during their lifetime. But after their deaths, he decided to cast them as heroes.

Penrose took this spiel on the road. It was a spectacular success in a Christian nation that believed in Manifest Destiny and admired missionaries. Penrose went to Chicago, sold the lie to a very rich man and a powerful newspaper editor. He then shared the story on the East Coast as he traveled between Philadelphia and Boston among some of the richest Protestants in the country.

Penrose raised the equivalent of millions of dollars. That money saved Whitman College. Penrose went on to serve as president of the college for 40 years and, from the mid-1890s until his death, he kept repeating the Whitman lie despite overwhelming evidence that it was not true.

Penrose, though, was much more than merely a factually challenged fundraiser. He was also a scholar obsessed with building a first-class, Williams-like liberal arts college in the Pacific Northwest. And, by the 1920s, he had succeeded. Whitman became one of the best private colleges in the Pacific Northwest, one of the best in the West. And it still is. It ranks among the top liberal arts colleges in America. Penrose used an absurd lie to create a fine school. It has educated many, many thousands of the people who now are leaders in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Robin Lindley: Was Penrose aware that the Whitman story he shared through the years was a lie?

Blaine Harden: He never acknowledged that, but the people who knew him also knew how sophisticated and well-read he was. He taught Greek and Latin, and he was expert in many fields. He probably knew that the story he told was nonsense, but it was such a useful story for the college that he kept telling it until the day he died.

Robin Lindley: Your book deals with the legacy of Marcus Whitman at Whitman College in recent years and some of the controversy. You indicate that most of the Whitman students now don’t know much about Marcus Whitman.

Blaine Harden: Penrose was around until the 1940s. After that, the school quietly walked back its commitment to the false story, without formally denouncing it. It didn’t say we were wrong, and we built this institution on the lie. It has never said that to this day, but they backed away from it. Two historians who taught at Whitman said that the college could not have survived without the lie. In fact, they published papers and books to that effect and gave speeches at the school about that. No president of Whitman College has formally acknowledged this truth. Instead, the college quietly backed away from the lie. It stopped taking students from the campus out to the massacre site where the National Park Service has honored the Whitmans. Most students since the sixties and into the 21st century didn’t learn much about Marcus Whitman. The massacre and its relationship to the college and to the land that the school is built on was fuzzily understood. There was a deliberate plan by college administrators to move away from the myth, focusing instead on more global issues.

But in the past ten years students have become very much aware of the actual history. They’ve changed the name of the college newspaper from The Pioneer to the Wire. They’ve changed the name of the mascot from the Missionaries to the Blues. A portrait of Narcissa Whitman was defaced and a statue of her was quietly removed from campus. There’s a statue of Marcus Whitman that the students want to remove; many professors hate it. In fact, a faculty committee located the statue on a far edge of the campus, near a railroad track. One professor said they put it there in the hope that a train might derail and destroy it. I asked the administration, as I finished the book, about any plans to change the name of the college or thoroughly investigate its historical dependence on a lie. The answer was no.

The college has, to its credit, become much more involved with the Cayuse, the Umatilla, and the Walla Walla tribes who live nearby on the Umatilla Reservation. They’ve offered five full scholarships to students from the reservation. They’re also inviting elders from the tribes to talk to students. Students now are much more knowledgeable than they were in the past as the result of raising awareness.

Robin Lindley: You detail the lives of white missionaries in the Oregon region. Most people probably thought of missionaries as well intentioned, but you capture the bickering between the Protestant missionaries and their deep animosity toward Catholics. A reader might wonder about this feuding and the tensions when all the missionaries were Christians. Of course, as you stress, it was a time of strong anti-Catholic sentiment, xenophobia and nativism in America.

Blaine Harden: The Protestants and the Catholics were competing for Indian souls. In the early competition, the Catholics were lighter on their feet. They didn’t require so much complicated theological understanding among the Native Americans before they would allow them to be baptized and take communion. Basically, if you expressed an interest, you were in. But the Protestants were Calvinists. They demanded that tribal members jump through an almost endless series of theological and behavioral hoops before they could be baptized. Very few Indians were willing to do what the Protestants required.

The Protestants saw the Catholics gaining ground, and they deeply resented it. In fact, they hated the Catholics, and they viewed the Catholic Church as controlled by a far-off figure in Rome. Catholics represented, in the minds of many of the Protestants, an invasion of immigrants. In the 1830s through the 1860s, the United States absorbed the biggest percentage of immigrants in its history, including Catholics from Italy and Ireland. Those immigrants not only came to East Coast cities, but they also came to Midwestern cities, and they also came west. If you were anti-Catholic, you were anti-immigrant. The anti-immigrant stance still has a resonance today.

Spalding was a Protestant who had gone to school at Case Western in Cleveland, where he was drilled in anti-Catholic madness. He created the Whitman lie to wrap all that prejudice, all that fear, into an appealing tale of Manifest Destiny with Catholics as villains.

Robin Lindley: And Spalding was in competition with Whitman although were both trying to convert people to the same Protestant sect.

Blaine Harden: To some extent, there was competition even among the Protestant missionaries, but the real competition was between the Protestants and the Catholics. The anti-Catholicism that was engendered by Spalding and by the Whitmans persisted in Oregon where anti-immigrant and anti-Black provisions were written into the State constitution. Blacks were banned from the state of Oregon until the 1920s under the state law. The Ku Klux Klan had a very receptive audience there and a fundamental hold on the politics of Oregon for many years. Oregon, in fact, banned parochial schools until that ban was overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States in a landmark case.

The spillover from this conflict between the Catholics and the Protestants in the 1830s and forties and fifties lasted well into the 20th century. Even now, there’s strong strain of anti-immigrant and anti-Black and anti-minority sentiment in Oregon. It’s a minority view, but it hasn’t disappeared.

Robin Lindley: You set out the context of the Whitman story at a time when Americans embraced Manifest Destiny and the white settler conquest of the West. You vividly describe how the settlers and missionaries treated the Indians. You detail the cycles of dispossession as the Cayuse and other tribes were displaced and attacked violently as whites overran the region.

Blaine Harden: The Cayuse and the Walla Wallas and the Umatillas controlled as their traditional lands an area about the size of Massachusetts, north and south of the Columbia River in what became the Oregon territory.

In 1855, the federal government sent out a governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, who was to negotiate the taking of Indian land. There was a large meeting right where the campus of Whitman College is today. All the tribes attended. At first, the Cayuse were offered nothing. They were told to move to a reservation that would be established for the Yakima nation, and they refused. They made it clear to Stevens and the 25 to 30 white soldiers that were with him that, unless they got a better deal, they might kill all the whites at the meeting.

Robin Lindley: Weren’t the Cayuse more belligerent than other tribes in the region?

Blaine Harden: They were known for being tough and willing to resort to violence to get what they wanted. So Stevens recalculated and decided to give them a reservation on traditional Cayuse land with the Umatillas and the Walla Wallas. It is near what’s now Pendleton, Oregon. The three tribes had treaty-guaranteed control of this land after 1855, but white people living around the reservation coveted its best farmland and kept pressing the state and federal government to allow them to take it. White people didn’t take all the reservation, but white leases and white ownership created a checkerboard of non-Indian landholdings. By 1979, the reservation had shrunk by nearly two-thirds.

From 1850s all the way to 1980s, the tribes who lived on that reservation were marginalized. They were poor. They were pushed around. They didn’t have self-government. There was a lot of hopelessness. There was also a lot of alcoholism and suicide, and a lot of people left the reservation. It was a situation not unlike reservations across the west.

Robin Lindley: You recount the investigation of the Whitman murders, if you could call it that. Five members of the Cayuse tribe were eventually arrested and tried for killing the Whitmans and eleven other white people in the 1847 massacre.

Blaine Harden: By the time of the Whitman killings, there were more white people in the Oregon Territory than Native Americans. Most of that was because of disease. About 90 percent of Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest died in the first 50 years of white contact.

In any case, the white majority wanted vengeance and they wanted justice for the massacre. They wanted to round up the perpetrators and hang them. And they did. They sent an army unit to round up some suspects. They captured five Cayuse men. Whether these were all involved in the killing, it’s not clear. One of them almost certainly wasn’t involved. But at least two were clearly involved. The role of the other two is not so clear.

The detained men became known as the Cayuse Five, and they were tried eventually in Oregon City, now a suburb of Portland. They were convicted and hanged before a huge crowd. Thousands of people watched the hanging and then, once they were dead, they were loaded on a wagon and the bodies were taken to the edge of town and buried in an unmarked grave that’s been lost. The loss of the bodies has tormented the Cayuse. They want to find those remains and bring them back to their land to gain some closure on this business. And they still are looking and there’s been some progress. They might be under a Clackamas County gravel yard used for a snow mitigation, but that hasn’t yet been resolved.

Robin Lindley: From your book, it’s unclear if the Cayuse defendants even understood what was going on at trial, let alone had an opportunity to confront their accusers.

Blaine Harden: They had lawyers, and the lawyers presented a couple decent arguments. One argument was that the land where the killing of Marcus Whitman and his wife and eleven others occurred, was not US territory, and it also wasn’t Indian territory under federal law. It was basically a no man’s land governed by a treaty between the British and the Americans with no law enforcement infrastructure or legal authority. Because it occurred there and because the traditional laws of the Cayuse said that failed medicine men can be killed, the lawyers argued that no one could be prosecuted for the murders. The lawyers argued that American courts had no jurisdiction. The judge rejected the argument because he knew that if the Cayuse Five weren’t legally convicted, they would be lynched. That was the sentiment of the time, so they were legally convicted and then quickly hanged.

Robin Lindley: And you provide the context of that verdict and sentence by recounting how often Native Americans were hanged throughout the country. And, in places like California, it seems white citizens were encouraged under law to exterminate the Indian population and were rewarded for it.

Blaine Harden: There was a pattern that repeated itself again and again and again in the South, in the Southwest, in California, in Minnesota and in Washington State. White people would come into an area where Native Americans were hunting and fishing and doing things that they’d been doing for hundreds and hundreds of years. And they would crowd out the Indians, push them away, and take the best land. Then sooner or later, a group of Natives Americans would strike back. Sometimes they’d kill some white men, sometimes they’d kill some children, sometimes they’d kill women and children. And then, after that provocation, after the killing of whites, there was a huge overreaction by whites and disproportionate justice was enforced. Native people were rounded up, murdered, and hanged, and survivors were moved off their land.

In Minnesota, more than 300 Native Americans were arrested and condemned to death following a fierce war. About forty of them eventually were hanged and the entire Indian population was removed from Minnesota. It happened again in Colorado. It happened in California. Indians were punished with extreme prejudice.

The goal of the violence against Native Americans was to clear land for white settlement. The provocations that produced an Indian backlash were the perfect way to advance Manifest Destiny: They killed our women and children so we must kill them all or remove them all. The Whitman case is one of the earlier examples. The trial that occurred in Oregon City in the wake of the Whitman killings was well documented and covered by the press. There’s a precise, verbatim record of what happened there that I used in the book.

Robin Lindley: The Spalding tale and the treatment of Native Americans, as you note, were examples of virulent racism. The Indians were seen as backward and inferior in a white supremacist nation.

Blaine Harden: Yes. There is a link between the way whites in the Pacific Northwest treated Native American and the way whites in the South treated Blacks after the Civil War. There was a defense of state’s rights against an overbearing federal government. The defenders of state’s rights were Civil War generals and big statues of these Confederate generals went up throughout the early 20th century in every small, medium, and large city in the South.

In the same way, the statues of Marcus Whitman that went up in the Pacific Northwest and in Washington DC represented a whitewashed, politically accessible self-congratulatory story about land taking. That’s why the Whitman story persisted so long.

I think there is a certain sanctimony about living in the liberal Pacific Northwest—that we understand the power and the poison of racism, particularly when you look at it in the context of American South. But if you look at it in the context of whites and Native Americans around here, the legacy of racism is obvious and enduring. I do think, however, that there’s been a sea change in the past ten or fifteen years in education in schools at all levels, and books like Murder at the Mission have proliferated, so I think there is a much more sophisticated understanding of racism in the West.

Robin Lindley: You conclude your book with how the Cayuse nation has fared in the past few decades and you offer some evidence of positive recent developments after a history of racism, exploitation, and marginalization.

Blaine Harden: Yes. The book ends with an account of how the Umatilla Reservation has had a Phoenix-like rebirth. That’s a story I report I didn’t know when I started the book. And it’s hopeful and it speaks well for the character of the tribes and some of the people who engineered this transformation. It also speaks well for the rule of law in America because the treaty that gave them the land promised certain rights under the law. The treaty was ratified by the US Senate, but its language was largely ignored for nearly a century. However, starting in the 1960s and 1970s, federal judges started to read the language of that treaty, and they decided that the tribes have guaranteed rights under the law, and we are a country of laws, and we’re going to respect those rights.

Slowly, self-government took hold on the reservation. Young people from the reservation were drafted to serve in World War II and then in Korea and Vietnam. There was also the Indian Relocation Act that moved a lot of young people to cities like Seattle, San Francisco, and Portland. While they were away, many got college educations. They learned about business management and land use planning. Some of the principal actors in the rebirth of the reservation became PhD students in land use planning. Others became lawyers. They understood their rights under state and federal law.

The provocations that produced an Indian backlash were the perfect way to advance Manifest Destiny: They killed our women and children so we must kill them all or remove them all.

Starting in the seventies and eighties, these men and women went back to the reservation and started organizing self-governance. They started suing the federal government and winning some large settlements for dams that were built on the Columbia. With that money, they slowly started to assert their rights. They reclaimed the Umatilla River, which had been ruined for fish by irrigators who took all its water during the summer. Salmon couldn’t swim up and down.

The big thing for the tribes happened in the early 1990s with the Indian Gaming Act, which allowed them to build a casino on the reservation. The reservation is on the only interstate that crosses northwest Oregon, east to west, and that highway runs right past the casino. The casino turned out to be spectacularly successful. By the time money started to flow, the tribe was well organized enough to use that money to do a whole range of things to improve life on the reservation ranging from better medical care to better educational facilities to broader opportunity for businesses.

Gambling money has been a remarkable boon to health. Since it started flowing into reservation programs, rates of suicide, alcoholism, smoking, obesity, and drug abuse have all declined. There are still serious problems, but no longer cataclysmic, existential threats to the survival of these reservations. Money with good planning and investment of the gaming money led to building offices, projects for big farming, and more. They’ve been successful. And the tribe has acquired major commercial operations around Pendleton. They own one of the biggest outdoor stores and a few golf courses. They are political players in Eastern Oregon that politicians statewide respect. This is recompense for past wrongs.

Robin Lindley: Thanks for sharing this story of the Cayuse and their situation now. You interviewed many tribal members for the book. How did you introduce yourself to the tribe and eventually arrange to talk with tribal elders? There must have been trust issues.

Blaine Harden: There were difficulties and it’s not surprising. I’m a white guy from Seattle and my father had built dams that flooded parts of the Columbia plateau. My requests to have in-depth interviews with the elders were not looked upon with a great deal of favor for sound historical reasons.

They were distrustful, but I managed to make an acquaintance with Chuck Sams, who was at that point in charge of press relations for the reservation. He agreed to meet with me and, like many of the other influential people on the reservations, he had gone to college. He also had served in the military in naval intelligence. I wrote a book about an Air Force intelligence officer who was very important in the history of the Korean War. Sams read the book, and I think he thought I was a serious person who was trying to tell the truth. He slowly began to introduce me to some of the elders.

Finally, I sat down with two of the elders who were key players in the transformation of the reservation. They talked to me for hours and then I followed up by phone.

Robin Lindley: You were persistent. Have you heard from any of the Cayuse people about your book?

Blaine Harden: Yes. The key men that I interviewed have been in contact. They like the book. It’s now sold at a museum on the reservation.

Another thing about this book is that I asked several Native Americans to read it before publication. They helped me figure out where I’d made mistakes because of my prejudices or blind spots. Bobbie Connor, an elder of the tribe on the reservation and head of the museum there, pointed out hundreds of things that she found questionable. She helped me correct many errors. The book was greatly improved by her attention to detail.

Robin Lindley: It’s a gift to have that kind of support.

Blaine Harden: Yes. I hadn’t done that with my five previous books but in this case, it really helped.

Robin Lindley: Your exhaustive research and astute use of historical detection have won widespread praise. You did extensive archival research and then many interviews, including the crucial interviews with Cayuse elders. Is there anything you’d like to add about your research process?

Blaine Harden: There have been many hundreds of books written about the Whitman story in the past 150 years. A lot of them are nonsense, but there is a long historical trail, and it goes back to the letters that the missionaries wrote back to the missionary headquarters in Boston that sent them west.

Many of the missionaries wrote every week, and these were literate people who weren’t lying to their bosses in most cases. They were telling what they thought. All those letters have been kept and entered a database so you can search them by words. The research on Spalding particularly was greatly simplified because I could read those databases, search them, and then create chronologies that were informed by what these people wrote in their letters. And that really helped.

Robin Lindley: Didn’t many doubts arise about Spalding in these letters?

Blaine Harden: Yes, from a lot of the correspondence I reviewed. The correspondence database simplified the research, and it also made it possible to speak with real authority because the letters reveal that Spalding says one thing in the year it happened, and then 20 years later, he’s telling a completely different story. It’s clear that he’s lying. There’s no doubt because the primary sources tell you that he’s lying, and that’s why the professor at Yale in 1900 could say that Spalding’s story was nonsense. And looking back at the documents, you can see just how ridiculous it was.

I also studied the records that are were kept by the people who raised money for Whitman College about how they did it, the stories that they were selling, and then how they panicked when it became clear that their story was being questioned.

Robin Lindley: What did you think of the replacement of the Whitman statue at the US Capitol in Washington DC with a statue of Billy Frank, a hero for Native American rights?

Blaine Harden: There’s poetic justice to having Billy Frank’s statue replace the statue of Whitman. It makes a lot of sense because he empowered the tribes by using the rule of law. Billy Frank Jr. went out and fished in many places and got arrested, but he fished in places where he was allowed to under federal and state law. He kept asserting his rights under the law that the federal government and the states had on the books. That’s in effect what happened with the Umatilla and Cayuse reservation. They asserted their rights under the law and their conditions improved.

The one thing about Whitman is that he didn’t make up the lie about himself. He was a man of his time who thought the way people of his time thought. And we can’t blame him for that.

Robin Lindley: It seems that there’s a lot of material in your book that hasn’t been shared or widely known before.

Blaine Harden: Some of the actual story was widely known for a while, and then it just disappeared. It didn’t become a part of what was taught in public schools. And into the 1980s, a phony version of history was taught officially in the state of Washington.

Robin Lindley: Thank you Mr. Harden for your patience and thoughtful remarks on your work and your revelatory book, Murder at the Mission. Your book provides an antidote to a foundational American myth and serves as a model of historical detection and investigation. Congratulations and best wishes on your next project.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.