The Most Wanted Man in China

The fascinating memoir of Fang Lizhi, the astrophysicist who inspired Chinese pro-democracy student protesters in the late 1980s, is now released nearly four years after Fang's death in exile, despite political obstacles preventing its publication in China.

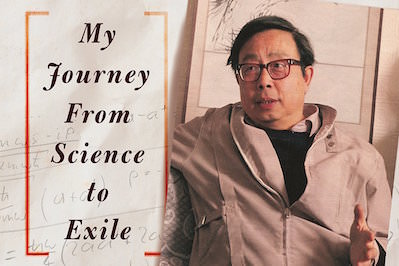

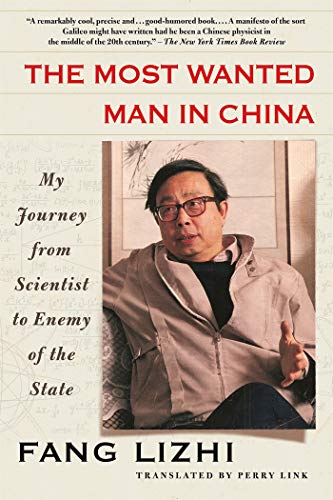

“The Most Wanted Man in China: My Journey From Scientist to Enemy of the State” A book by Fang Lizhi, translated by Perry Link To see long excerpts from “The Most Wanted Man in China” at Google Books, click here.

Fang Lizhi, the astrophysicist who inspired Chinese pro-democracy student protesters in the late 1980s, gives a fascinating and insightful account of his life in a memoir now published nearly four years after his death in exile. In “The Most Wanted Man in China,” Fang takes us from the 1940s, when he joined an underground Communist Party youth organization, through the years when he was expelled from the party and sent to the countryside to dig wells, labor in a coal mine and work on a railroad construction site.

Fang’s experiences working in the countryside, his scientific approach to the pursuit of truth and his growing knowledge of Western concepts of freedom and democracy left him disillusioned with Marxism and Maoism. They also left him outspoken in his criticism of the Communist system.

I knew Fang when I was a reporter for The Washington Post based in Beijing from 1985 to 1990. Like many of my colleagues at the time, I became aware of Fang in 1986, when university students began calling for a more democratic system and an end to corruption and nepotism in China’s Communist Party. Fang was the vice president of a science and technology university in a remote city in southern China that most of us had never visited.

The students were taking advantage of Communist Party chief Hu Yaobang’s declarations that modernization could not take place without democracy. Party elders ousted Hu in early 1987 for failing to crack down on the students, among other things.

But little did I understand at that moment in 1986 the electrifying effect that Fang’s rhetoric was having on students at a number of Chinese universities, who like many before them considered themselves to be the conscience of the nation. In one of his boldest moves, Fang appealed directly in January 1989 to Deng Xiaoping, China’s supreme leader, to release the country’s political prisoners, something that few Chinese would have dared to do at the time.

In June 1989, Fang and his wife, physicist Li Shuxian, were accused of being “black hands” behind the student-led protests at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, which ended on June 4 when Chinese troops killed hundreds of demonstrators. As Fang’s account makes clear, he and Li had not played any direct role in the demonstrations. Nonetheless, they were placed on a wanted list and sought refuge in the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, where they stayed for more than a year before being allowed to leave the country.

During that period, Fang wrote his memoir. It is only now being published because political obstacles prevented it from appearing in China and translation hurdles slowed its release in English. Its translator is Perry Link, an expert on Chinese literature and culture at the University of California at Riverside. The memoir is almost certain to be censored in China, as was anything Fang wrote over the past few decades. Link notes in his afterword that Fang couldn’t publish inside China during his more than 20 years in exile, which he spent mostly in the United States serving as a physics professor at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Even his articles on pure science have been censored. The government has banned “the very mention of Fang’s name,” writes Link, who himself has been unable to obtain a visa to travel to the People’s Republic since 1996.Although I thought I knew quite a bit about Fang, his memoir contains much that is new and fascinating to me, starting with his joining a Communist front organization in Beijing at age 12. In the 1950s, as a brilliant physicist and loyal Communist Party member, he worked on the secret development of China’s first atomic bomb. Then in 1957 came Mao Zedong’s invitation to intellectuals to freely express criticisms of the party. Fang and other prominent physicists at Beijing University began preparing accounts of what they regarded as the party’s many shortcomings.

But Mao then launched an “Anti-Rightist Movement” directed at those who were speaking up. The party banned Fang and Li from teaching or publishing, though Li was allowed to stay on at Beijing University. Fang was sent to the countryside to be “educated” by laboring alongside poor farmers in a remote mountain village.

Fang had yet to lose hope for reform of the party from within, but he resented his forced separation from his wife, something required by the anti-rightist campaign. His descriptions of their separations and their brief reunions over the years are among the most touching themes in his memoir.

Unlike many intellectuals, Fang survived Mao’s disastrous Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976. But for more than a decade he and his wife were again forced to live apart, she in Beijing and he in southern China. He didn’t get to see his second son, Fang Zhe, for the first time until 1969, when the boy was nearly a year old.

The Communist Party had expelled Fang but readmitted him in 1979. But by that time, he says, “not a trace was left” of the idealism that had originally brought him to the party.

Party conservatives, or leftists, still mistrusted him, partly because of his “unorthodox public talks.” But with Hu Yaobang, a more liberal party secretary, in power, Fang gained prominence by being appointed in the early 1980s as vice president of the University of Science and Technology of China.

Disillusionment came inevitably, as he describes it, because he was a scientist and “science by nature weeds out ignorance.” He adds, “With or without an Anti-Rightist Movement, the split between scientists and the Party was bound to occur sooner or later.”

Addressing weighty subjects such as this or the suicides of colleagues who were forced to inform on one another during Mao’s campaigns, Fang never falls into bitterness or despair. He also lightens the narrative throughout with jabs at the absurdity of party dogma, including a requirement in the 1960s that physicists cite Mao as “the supreme helmsman in their work.” The party for years opposed the study of cosmology — the origin and structure of the universe — because scientific findings conflicted with Marxist dogma.

Fang achieves a lyrical quality when discussing the study of astrophysics and cosmology, two of his favorite subjects, as well as the beauty, harmony and wonders of the universe. He also writes vividly of the virtues of manual labor and his respect for the farmers, well-diggers, brick makers, coal miners and railroad construction workers with whom he toiled in the countryside.

Dan Southerland, a former Beijing bureau chief for The Washington Post, is the executive editor of the congressionally funded Radio Free Asia.

©2016, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.