The Moment of Decision: Should We Kill Dzhokhar Tsarnaev?

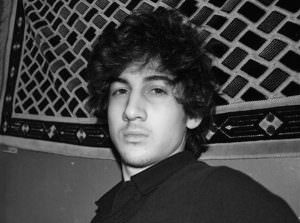

Unlike the guilt phase of the trial, the outcome of which was never in doubt, the penalty segment will be a slugfest pitting two diametrically opposed narratives of criminal justice. Boston Marathon bombing defendant Dzhokhar Tsarnaev depicted at a pretrial hearing in federal court in Boston. (AP / Jane Flavell Collins)

Boston Marathon bombing defendant Dzhokhar Tsarnaev depicted at a pretrial hearing in federal court in Boston. (AP / Jane Flavell Collins)

Should we kill Dzhokhar Tsarnaev?

No matter what any of us may think, the only people with the legal authority to answer the question are the 12 members of Tsarnaev’s jury, who will begin hearing sentencing evidence when the penalty phase of the trial commences April 21. That’s the day after this year’s Boston Marathon, which is staged annually on Patriots’ Day.

Should the jury opt for life, the 21-year-old defendant is likely to spend the rest of his time on earth at the Supermax federal penitentiary known as ADX in Florence, Colo. There, he will be in solitary confinement 23 hours a day, alongside such inmates as Unabomber Ted Kaczynski, shoe bomber Richard Reid and 9/11 co-conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui.

Should the jury choose death, barring an appellate court reversal Tsarnaev will meet his fate at the tip of a needle, most likely at the prison in Terre Haute, Ind., which houses the federal government’s death row. Following in the footsteps of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, drug kingpin Juan Garza and Louis Jones Jr.—the only three condemned federal prisoners actually put to death since the restoration of the federal death penalty in 1988—Tsarnaev would be executed by lethal injection.

Unlike the guilt phase of the trial, the outcome of which was never in doubt, the penalty segment of Tsarnaev’s case will be a slugfest pitting two diametrically opposed narratives of criminal justice.

In accordance with the rules of “guided discretion”—the name given to the version of capital punishment that the Supreme Court’s 1976 Gregg v. Georgia decision ruled constitutional—juries must weigh aggravating and mitigating factors, including the nature of the charged offense and the defendant’s background and character, to determine whether he or she should live or die.

As outlined in the Notice of Intent to Seek the Death Penalty filed in January 2014 by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts, the prosecution will base its call for death on such aggravating factors as the premeditated nature of the 2013 marathon bombing perpetrated by Tsarnaev and his older brother, Tamerlan; the impact of the bombing and subsequent murder of Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus police officer Sean Collier on the victims and their families; and what the prosecution terms Tsarnaev’s “betrayal of the United States.” In the eyes of the Justice Department, Tsarnaev isn’t just a multiple murderer—the bombing killed three people, and Collier was shot to death during the brothers’ getaway—he’s a bloodthirsty Islamic terrorist.

If the guilt phase is any indication, the prosecution will emphasize the terrorism angle above all. Assistant U.S. Attorney Aloke Chakravarty invoked the root word “terror” no fewer than 32 times in his April 6 closing argument:

The defendant brought terrorism to backyards and to main streets. The defendant thought that his values were more important than the people around him. He wanted to awake the mujahidin, or the holy warriors, and so he chose marathon Monday. He chose a family day of celebration. He chose a day when the eyes of the world would be on Boston, a sporting event celebrating human achievement. He chose a day where there would be civilians on the sidewalks. And he and his brother targeted civilians on the sidewalks. And he and his brother targeted those civilians, men, women and children, because he wanted to make a point. He wanted to terrorize this country. He wanted to punish America for what it was doing to his people.

As reported by The Boston Globe, toward the end of his argument Chakravarty played a multimedia medley of gruesome crime-scene photos on the court’s television screens, accompanied by the soundtrack of a nasheed—a jihadist chant associated with Anwar al-Awlaki, the U.S.-born al-Qaida propagandist killed in 2011 by an American drone strike in Yemen—that was found on a CD the brothers owned.

“They were the mujahidin,” said Chakravarty, reminding the jury of the brothers’ purpose in detonating their pressure-cooker, shrapnel-filled explosives, “and they were bringing their battle to Boston.” The prosecution’s entreaty, plainly, was one of vengeance. And in the guilt phase, it worked to perfection, as the jury returned guilty verdicts on all 30 counts charged in the indictment against Tsarnaev.

Will the same strategy succeed in the penalty phase?

Of all the venues in the United States, Massachusetts is among the least amenable to capital punishment. The state abolished the death penalty in 1984, and the last execution there was carried out in 1947. Public opinion polls of Boston residents conducted in 2013 and in late March showed that strong majorities, ranging from 57 percent in the earlier poll to 62 percent in last month’s survey, favored a sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole for Tsarnaev rather than the death penalty.

But the Tsarnaev prosecution is based solely on federal law, and the members of the jury are not exactly typical Bostonians when it comes to their opinions about the death penalty. Consisting of five men and seven women, the jury is almost exclusively white. It does contain a person of Iranian descent.

More important, each juror has been “death-qualified”—meaning that each has met a standard found to be constitutional by the Supreme Court, having declared during voir dire that he or she would be able to impose the death penalty should the evidence warrant it. A solid body of research indicates that such jurors are more likely than those morally opposed to capital punishment to be racist, sexist, homophobic and politically conservative, and that they are more inclined to give greater weight to aggravating factors than those that might mitigate punishment.

In addition, a multistate study conducted in the 1990s by the Albany, N.Y.-based Capital Jury Project found that nearly 50 percent of death-qualified jurors had decided what sentence they would impose before the penalty phases of their cases even began. Still, the Justice Department’s track record in recent death penalty cases has been underwhelming. Under the Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994 and its 1988 predecessor, prosecutors have tried 229 capital cases before juries, garnering just 79 death sentences, the vast majority of which remain under appeal.

To win a death sentence against Tsarnaev, prosecutors will have to prove any alleged aggravating factors beyond a reasonable doubt. They also will have to secure a unanimous jury verdict for death. Tsarnaev, by contrast, will be required to prove mitigating circumstances only by a preponderance of the evidence, a far more lenient standard. And if only a single juror refuses to vote for death, Tsarnaev will receive a life term.

Mounting a case for life, however, will be no easy task, even for a seasoned defense team headed by Judy Clarke, whose past clients include Kaczynski; Susan Smith, the South Carolina mother who drowned her two children; Eric Rudolph, the Atlanta Olympics bomber; and Jared Loughner, who shot and killed six people and severely injured former Arizona Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords at a Tucson community meeting. All were spared the death penalty, and all but Smith worked out pretrial plea bargains for life sentences.

The goal of every capital defense attorney at the penalty phase is to humanize the accused and persuade the jury to exercise mercy. During the guilt phase, Clarke and her colleagues signaled that their case for mitigation will be constructed on the claim that the elder Tsarnaev brother, Tamerlan, was the dominant actor in the bombing and the killing of Officer Collier, and that Dzhokhar would never have lashed out on his own but for the senior sibling’s overbearing influence.

Yet even if the defense team shows that Dzhokhar was subordinate to Tamerlan, it will have to do more to prevail. No doubt the team will emphasize that Dzhokhar was only 19 at the time of the bombing. It will also elicit testimony from mental health experts, as well as from Dzhokhar’s friends and perhaps his two sisters, who reportedly live in New Jersey, to sketch a nuanced portrait of a troubled and confused young man whose tumultuous family immigrated to the U.S. from Kyrgyzstan when he was 8 years old.

Tsarnaev’s parents, now divorced and residing in the Russian republic of Dagestan, presumably will not be summoned. Tsarnaev’s mother, Zubeidat, faces arrest for a 2012 shoplifting charge should she return to the U.S.

It is possible that Tsarnaev will be called to testify on his own behalf, but the risks of exposing him to what would surely be a withering cross-examination are likely prohibitive. Research suggests that when capital defendants testify, jurors more often than not think they are lying or showing no remorse.

In the final analysis, no matter who testifies for the defense, the most daunting challenge for Tsarnaev will be dealing with the terrorist label. Will Clarke and company argue—as some observers have suggested—that their client’s life should be spared because executing him would work as a rallying cry for other terrorists plotting against America? Or will the defense try to explain—though not excuse—Tsarnaev’s crimes as an ill-conceived juvenile overreaction to the staggering horrors of the U.S. war on terror, which is estimated to have caused over 1.3 million fatalities in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan since the 9/11 terrorist attacks?

Whatever choices Clarke and her team make, one thing seems certain: If the prosecution persuades the jury that returning a death sentence is its only patriotic option, Tsarnaev won’t live to see his thick brown hair thin and fade to gray, even allowing for a lengthy appeal.

Should we kill Dzhokhar Tsarnaev? Readers of this column know that I think capital punishment is a barbaric practice that ought to be declared unconstitutional. But you and I don’t get to decide. Only the 12 death-qualified citizens seated in the jury box get to make the call. Let’s hope they make the right one.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.