The Missile Crisis That Never Went Away

Fifty years after the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, and more than 20 years after the end of the Cold War, the US and Russian nuclear confrontation continues Each nation still keeps a total of about 800 ICBMs at launch-ready status, ready to be fired on a few minutes' warningWith approximately 1,700 nukes at launch-ready status 50 years after the Cuban missile crisis, it is naive to assume that Russia and the U will never again be in a military confrontation.

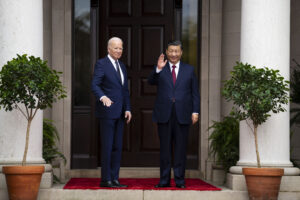

By Steven Starr, David Krieger and Daniel EllsbergTuesday marks the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Cuban missile crisis, a 13-day confrontation between the United States, the Soviet Union and Cuba that almost ended in nuclear war. On Wednesday, Daniel Ellsberg and David Krieger, two of the authors of this piece, will stand trial on charges related to protesting the test launch of an ICBM in February 2012.

Fifty years after the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, and more than 20 years after the end of the Cold War, the U.S. and Russian nuclear confrontation continues. Each nation still keeps a total of approximately 800 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), armed with more than 1,700 strategic nuclear warheads at launch-ready status, able to be fired with only a few minutes’ warning.

The U.S. now has 450 land-based Minuteman III missiles that carry 500 strategic nuclear warheads. As their name implies, they require at most several minutes to be launched. The U.S. also has 14 Trident submarines and 12 are normally operational. Each Trident now carries about 96 independently targetable warheads and five Tridents are reportedly kept in position to fire their missiles within 15 minutes. This adds another 120 missiles carrying 480 warheads that qualify as being “launch-ready.”

The missiles and warheads on the Trident subs have been “upgraded” and “modernized” to make them accurate enough for first-strike weapons against Russian ICBM silos. Missiles fired from Trident subs on patrol in the Norwegian Sea could hit Moscow in less than 10 minutes.

Russia is believed to have 322 land-based ICBMs carrying 1,087 strategic nuclear warheads; at any given time, probably 900 of these are capable of being launched within a few minutes. Many of the Russian ICBMs are more than 30 years old. According to a former high-ranking Soviet officer, the commanding officers of the Russian Strategic Rocket Forces have the ability to launch their ICBMs directly from their headquarters, bypassing all lower levels of command.

The Russians also have nuclear submarines with ballistic missiles kept at launch-ready status, although Russian subs are not always kept in position to launch (unlike the U.S. Tridents). Missiles launched from Russian submarines on patrol off the U.S. East Coast could, however, hit Washington, D.C., in about 10 minutes.

The combined explosive power of all these U.S. and Russian launch-ready nuclear weapons is roughly equivalent to 250 times the explosive power of all the bombs exploded during the six years of World War II. It would require less than one hour for the launch-ready weapons to destroy their targets.

Both the U.S. and Russian presidents are always accompanied by a military officer carrying the “nuclear football” (called cheget in Russia), a communications device resembling a laptop computer, which allows either president to order the launch of his nation’s nuclear forces in less than one minute. Both nations still have officers stationed in underground ICBM command centers, sitting every moment of every day in front of missile-launch consoles, always waiting for the presidential order to launch.

For decades, hundreds of U.S. and Russian ICBMs have been kept at high-alert, primarily for one reason: fear of a surprise attach by ICBMs or SLBMs. Since a massive nuclear attack will surely destroy both the ICBMs and the command-and-control system required to order their launch, the military “solution” has always been to launch their ICBMs before the arrival of the perceived attack. And once an ICBM is launched, it cannot be recalled.

Following the Cuban missile crisis, both the U.S. and Russia developed and deployed highly automated nuclear command-and-control systems, which work in conjunction with a network of early-warning systems and their nuclear-armed ballistic missiles. The possession of this complex integrated network of satellites, radars, computers, underground missile silos, fleets of submarines, and bombers give both nations the capability and option to launch most of their ICBMs upon a warning of attack.

This creates the possibility of an accidental nuclear war triggered by a false warning of attack. During peacetime, when political tensions are low, conventional wisdom has it that there is essentially no chance that a false warning of nuclear attack could be accepted as true. However, during an extreme political crisis, or after the advent of military hostilities, such a false attack warning could become increasingly likely and vastly more dangerous.

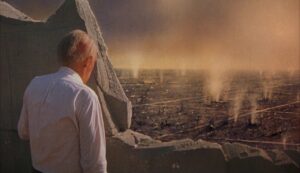

ICBMs remain out of the sight and the minds of most Americans, yet all the necessary military ingredients for Armageddon remain in place. And despite past presidential announcements that another Cuban missile crisis is “unthinkable,” it certainly remains possible.

It is naïve to assume that we will never again be in a military confrontation with Russia – particularly when U.S./NATO forces and U.S. nuclear weapons remain stationed near Russian borders in Europe, and we continue to surround Russia with missile defense facilities in the face of military threats against these facilities from the Russian president and top Russian military leaders. In March 2012, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov wrote to one of us (in a personal letter), “One cannot help agreeing to the conclusion that the deployment of [a] missile defense system at the very borders of Russia, as well as upbuilding the system’s capabilities, increase the chance that any conventional military confrontation might promptly turn into nuclear war.”

What happens if NATO collides with Russia somewhere in Georgia, Kaliningrad or perhaps Ukraine, shots are fired and Russia decides to carry out its threats to take out U.S./NATO missile defense installations? What happens if the U.S. should have a president who considers Russia to be America’s No. 1 geopolitical foe?

For many years it has been standard Russian military planning to preemptively use nuclear weapons in any conflict where it would be faced with overwhelming military force, for example, against NATO. The Russians oddly call the policy nuclear “de-escalation,” but it would be better described as “limited nuclear escalation. It was developed and implemented after the U.S. broke its promise not to expand NATO eastward (following the reunification of Germany) and NATO bombed Serbian targets.

The Russian “de-escalation” policy presumes that the use of nuclear weapons against the opposing side will cause them to back down; it is essentially a belief that it is possible to win a nuclear war through the “limited” use of nuclear weapons. But in the case of NATO, the war would be fought against another nuclear power.

Suppose that NATO responds instead with its U.S. tactical nuclear weapons now based in five European countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey)? Once an exchange of nuclear weapons takes place, what are the chances that the war will remain “limited”?

U.S. and Russian strategic war plans still contain large nuclear strike options with hundreds of preplanned targets, including cities and urban areas in each other’s nation. As long as launch-ready ICBMs exist, these plans can be carried out in less time than it takes to read this article. They are plans that spell disaster for both countries and for civilization.

Cooperation, rather than conflict, still remains possible. Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov writes, “Despite the growing hardship, we do not close the door either for continuing the dialogue with the U.S. and NATO on missile defense issues or for a practical cooperation in this field. In this respect, we find undoubtedly interesting the idea of a freeze on U.S./NATO deployments of missile defense facilities until the joint Russian-U.S. assessment of the threats is completed.”

This could be an important step toward lowering U.S.-Russian tensions, which continue to revolve around their more than 60-year nuclear confrontation. Ending this confrontation can prevent the next missile crisis. Another important step would be the elimination of first-strike ICBMs that continue to threaten the existence of our nation and the human race. This would increase the security of the American people, even if it were done unilaterally.

The U.S. and Russia remain obligated under terms of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty to pursue negotiations in good faith on nuclear disarmament in all its aspects. Fifty years after the Cuban missile crisis, it is well past time to conclude these negotiations. No issue confronting humanity is more urgent than bringing such negotiations to a successful conclusion and moving rapidly to zero nuclear weapons.

Steven Starr is an associate of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, a board member and senior scientist for Physicians for Social Responsibility, and director of the Clinical Laboratory Science Program at the University of Missouri. His website on the environmental consequences of nuclear war is nucleardarkness.org.

David Krieger is president of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation (wagingpeace.org). He is the co-author of the recent book, “The Path to Zero: Dialogues on Nuclear Dangers.”

Daniel Ellsberg is a distinguished senior fellow at the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation and a former strategic analyst for the Department of Defense. He released the Pentagon Papers in 1971.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.