The Man Who Invented Rock ’n’ Roll

This book is the story of Sam Phillips, who created the conditions for rock ’n’ roll, though he never wrote or played on any records, and his quest to rattle the foundations of American music and a country's ideas about itself.

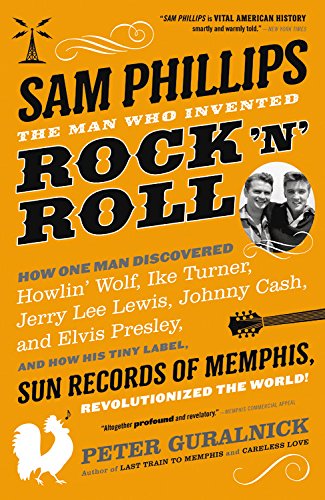

“Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ’n’ Roll” A book by Peter Guralnick To see long excerpts from “Sam Phillips” at Google Books, click here.

Collectors prize one obscure Sun recording at least as much as they cherish first editions of early Elvis Presley sides, or the trembling promise of the young Charlie Rich. The crucial moment comes after the second chorus in a 1953 number called “Time Has Made a Change,” the B-side to “Take a Little Chance” by Memphis musician Jim DeBerry. You can still hear it in its YouTube incarnation. It happens just as a wayward piano solo enters at around 1:35: A telephone goes off in the next room. Sun Records founder Sam Phillips felt strongly about leaving that mistake in — far from distracting the listener, he felt it made the listeners feel part of a common, everyday experience, a “perfect imperfection.” And it tied his whole musical aesthetic up in a symbol that echoes down through history.

“I love perfect imperfection, I really do,” Phillips tells biographer Peter Guralnick, “and that’s not just some cute saying, that’s a fact. Perfect? That’s the devil. Who in this world would want to be perfect? They should strike the damn thing out of the language of the human race. …”

Like his masterful biographies of Elvis Presley and Sam Cooke, Guralnick’s “Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ’n’ Roll” traces a charismatic figure through a cockeyed career. A critical argument has already broken out over that word “Invented” in the book’s subtitle. Most ascribe the distinction of “inventing” the genre to one of two performers and their specific songs: Ike Turner’s “Rocket 88” (from 1951), or Elvis Presley with “That’s All Right” (from 1954).

Phillips produced both of these recordings in all senses of that term; neither could have occurred without him. But to give him credit for “inventing” the new style above and beyond these performers rankles many. How could a “mere” producer “invent” a musical style? To be fair, Guralnick, like most authors, probably yielded to publisher Little, Brown’s marketing department’s inclination to incite such discussions, which help propel a backstage figure like Phillips into light normally reserved for onstage stars.

One of Phillips’ oldest industry friends, Billboard editor Paul Ackerman, put it best from his hospital bed: “Don’t ever let the world forget, Sam Phillips was the one who discovered rock ’n’ roll.”

Just think “discover” instead of “invent:” Semantics aside, this is the man who created the conditions in which rock ’n’ roll occurred, though he never wrote material or played on any records. And while his creative presence steers much of the early music’s great abandon and risk, Phillips’ role as “inventor” lay mostly in rolling tape at unlikely moments, and encouraging the least obvious musical elements from characters as varied as Presley, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis.

Phillips himself, while proud as any Jerry Lee Lewis track, emerges throughout Guralnick’s narrative as the type who never would have wanted such an argument about the distinction between invention and discovery to erupt about his role. He knew his place in history, and he knew how much luck and fate counted. As the youngest of seven, Phillips grew up as a farmer’s son in and around Florence, Alabama. He came of age during the Great Depression, and idolized the sideways genius of his half-blind, deaf and mute Aunt Emma, “the smartest woman in our whole family.” An influential Jimmie Rodgers song, “Waiting for a Train,” a deceptively simple blues, coaxed him out into the world toward that big city in the distance, Memphis, Tennessee.

Like a lot of engineers, Phillips started out in radio, and romanced that medium throughout his life. A jumpy type with too much energy for the day’s mere 24 hours, his early trials included two electroshock treatments for anxiety that seemingly helped him gain his footing as a young man. At a radio station, one Becky Burns latched onto him before she graduated high school and never let go, in spite of many serious girlfriends who literally crowded her out along the way. Sam and Becky married in 1943.

Guralnick emphasizes two important sub-themes throughout Sam’s life: first, the women who helped shape his vision, from his family and lovers to the all-female cast of WHER, the Memphis station he launched in 1956. Marion Keisker, his only Sun employee in the early days, helped him match the young Elvis Presley to an early song, and though their memories clash over how this happened, they both played important roles. Another woman, Alta Hayes of Dallas, reassured Sam he had a hit with Presley’s “That’s All Right” when plenty of radio people held their noses. Then comes the producer’s (and the music’s) lowly origins. In many rock histories, class gets obscured by race. It took both nerve and faith in the unknown for both Presley and Phillips to record black music (including the earliest sides from legendary Howlin’ Wolf). They both knew, however, that another source of the music’s emphatic grandeur, apart from race, lay in its self-conscious embrace of distinctly lower-class themes. In a flashy big city like Memphis, the blues signaled degeneracy. The blues were heard in flophouses and fringe bars, made by and for ne’er do wells — much the same way jazz proliferated on the streets of New Orleans 50 years previous. And the establishment music industry held its nose at this clientele’s taste at least as much as it segregated them by color.

Phillips understood Presley’s notably shy demeanor was a consequence of his hand-to-mouth upbringing, as was his identification with racial hardship. It’s one thing to sing and play material as incendiary as Presley did — it’s another thing to sense its commercial potential in the Brown v. Board of Education era. Just after an early take of “That’s All Right,” guitarist Scotty Moore exclaimed, “They’ll run us out of town!” This meant, roughly, that KKK gangs had lynched blacks for less. The brew held such a potent racial mix it wasn’t clear even to the musicians whether the fun these white fellas were having might cross some invisible cultural line between acceptance and doom. Phillips had the ear to hear both the music’s danger and promise, effrontery and potential, compression and explosiveness. Like a lot of characters in Guralnick’s books, Phillips surfaces as an invincible offstage personality who was relied on by performers to frame their settings, dynamics and opportunities.

But even after Phillips sold Presley’s contract to RCA for $40,000 and greeted Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins and others as successors, Phillips still struggled to pay his tax bills and meet his overhead. Even before the corporate overbite we live with today, independent labels like Sun had trouble surviving even when they hit gushers.

Keeping his own life story private and preferring to let his professional life speak for itself, Phillips refused to do interviews for a long time. Guralnick was famous for getting some of Phillips’ earliest and most comprehensive interviews starting in 1979, though Guralnick had already been knocking on his door for a while, and had befriended his older son, Knox.

After two decades of running Sun, dabbling in both Nashville studio and radio projects, and raising two sons, Phillips sold Sun to his good friend, Shelby Singleton. But Guralnick details what a family affair the whole Sun operation remained even after Singleton: Phillips’ brother Jud ran Jerry Lee Lewis’ career long after he signed with Mercury and focused on his C&W career, and both sons went into production and record promotion; Knox scored a hit with the Amazing Rhythm Aces, “Third Rate Romance,” in 1975. The Phillips boys grew up with familiar houseguests like Elvis and Jerry Lee and went on to help their father establish outposts in Nashville and a radio station in his Alabama hometown. Jud Phillips exaggerated his role as Jerry Lee Lewis’ manager, unnerving Phillips as only an older brother could.

These regional connections and personal anecdotes ground the story, paralleling the music’s down-home, lived-in feel. Guralnick reports Phillips as “vehement” on how Garth Brooks was “ruining country music,” and Presley contacts Phillips for advice when he returns to Vegas in the early 1970s, for this deathless advice: “‘Just put the rhythm out there, baby, just put it out there. That is your i-den-ti-fi-cation.’ To which, what else could Elvis do but assent?”

And while the pillars of Phillips’ life rest on how to frame aesthetic ideals, the story bulges with juicy asides, like this conversation between Jerry Lee Lewis and Lewis’ mother. ” ‘My mama,’ he said, ‘thought Chuck Berry was the king of rock ’n’ roll.’… When he asked her, ‘What about me, Mama?’ she gave him a loving but skeptical look. He was good, she said, ‘You and Elvis are good, son — but you’re no Chuck Berry. Chuck Berry is rock ’n’ roll from his head to his toes.’ “

While some of the later sections sag from the weight of Phillips’ interminable rants, Guralnick’s scholarship girds a loving portrait of a man, a mission and a quest to rattle the foundations of American music, and by extension, a country’s ideas about itself.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.