The Logbooks

Journalist Anne Farrow has written a profoundly personal reflection on historical memory, based on her discovery of Atlantic slave trade logbooks, and on her mother’s painful descent into dementia.

“The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory” A book by Anne Farrow

White Americans know that slavery was evil and was largely an issue in the Southern states. Millions of them also believe that it happened “long ago” and that it ended when President Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and when the Union defeated the Confederacy in the Civil War in 1865. Most, if pressed, would acknowledge that slavery had lingering effects past that time, but they typically regard slavery as an unfortunate relic of a bygone era. And often, when African-Americans mention slavery, some white Americans roll their eyes, sometimes even suggesting that they “move on and get over it.”

This response is merely one of many convenient myths about race, including the more recent one that America has become a “post-racial” society after the civil rights era and the election of Barack Obama as president of the United States in 2008. All of these myths are little more than self-serving rationalizations that discourage deeper, disconcerting examinations of historical racism and its enduring consequences.

“The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory” by New England journalist Anne Farrow is a profoundly personal reflection on historical memory, based on her discovery of logbooks from the Atlantic slave trade and on her mother’s slow and painful descent into dementia.

This especially engaging book examines the impact of the logbooks she discovered in 2004, written by 18-year-old Dudley Saltonstall, a crewman on three voyages of sailing ships owned by an affluent Connecticut merchant in the mid-18th century. Saltonstall and his fellow crew members were on a mission to West Africa to purchase black people as slaves — as he noted in the logbooks, “to take on slaves, wood, and water” — and to sell them to England’s colonial possessions in the Caribbean.

Some of the residual human “cargo” returned to New England, where their unwilling abduction and forced labor created the foundation of wealth both in that region and in America. These voyages were an integral part of the broader transatlantic slave trade that has forever despoiled Western history and inextricably links American racial politics of the present and recent past to its historical roots.

The 80 handwritten pages of young Saltonstall’s logbooks are an unnerving and intriguing primary source from 1757-1758. Much of that material is prosaic: the ships’ speed, the miles traveled, the direction of the winds, the crews’ eating and drinking supplies, and similar items. That is interesting for some historians, but is scarcely Farrow’s focus.

What matters is that the vessels were prison ships, traveling to slaving outposts on the West African coast, loading the kidnapped black women, men and children, and transporting them across the ocean to lives of servitude and brutality — if they survived the perilous journey at all. The author provides several excerpts of Saltonstall’s record of the voyages in revealing detail. Saltonstall was well aware of the bottom line: The more slaves who arrived in the Caribbean and America, alive and well, the more profit to be made by the owners.

But there were many perils. The slave ships were little more than floating torture machines, with their human cargo packed together in grotesquely tight arrangements, highlighted in numerous illustrations and Middle Passage works from African-American and other artists. The captives were held in intolerable heat and darkness and were seasick and in constant pain. As Saltonstall noted, some of the slaves were “not very well.”

They suffered from amoebic dysentery, which Saltonstall and others called the “bloody flux.” This was usually caused by contaminated food and water and transmitted by human feces and fecal bacteria. Many of the afflicted had as many as 20 bowel movements in 24 hours, suffering unbearable pain for several days before dying. Saltonstall notated their deaths as “died this day,” revealing no empathy whatsoever, merely recording this reality as a balance sheet debit item in a routine commercial transaction.

Farrow adds a profoundly emotional dimension to the historical record by providing this documentary evidence of callous indifference. This feature of her book is one of its finest contributions, encouraging readers to understand history in human terms, far beyond the numbing facts and statistics of conventional historical texts. As she notes, slavery was no “sad chapter” in an otherwise glorious history; it is the book itself, an unremitting story of unspeakable human horror, with profoundly disturbing ramifications well into the 21st century.

The author augmented her discoveries by traveling personally to Bunce Island (called Bence Island in the logbooks) in Sierra Leone, the setting for the slave depot where Saltonstall and his shipmates went to collect their human victims. While there, she experienced the powerful emotions any sensitive person would feel at such a site. She could imagine the bound and bewildered captives, walking under guard to the slave ships, looking back at their final glimpse of African soil as they exited the slave house, or, as Saltonstall recorded it in the logbooks, “the factory.” Language truly matters.

One fascinating issue Farrow raises in “The Logbooks” concerns the grommetos, the black Africans who participated in the slave trade in order to avoid being sold into slavery themselves. At the height of the island’s prosperity from this human commerce, as many as 100 grommetos lived and worked there. When Farrow traveled to Sierra Leone, she met with some of their descendants and asked about their feelings regarding their ancestors’ participation in the slave trade. Not surprisingly, she met with defensiveness. The village chief was angry at her inquiry. He asserted that the people sold into slavery were criminals and victims of war — patent rationalizations that Farrow properly disbelieved. He told her that his people had done what they had to do to survive. This is, to be sure, an understandable response, but it hardly addresses the deeper issues of human complicity in injustice, an issue that has continued to bedevil humanity well into the 21st century.

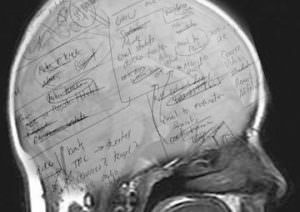

The parallel narrative in “The Logbooks” is the heartbreaking story of Farrow’s mother’s struggle with and ultimate death from dementia. This is an all too familiar saga for millions of people in America and elsewhere. They watch helplessly as their aging parents descend into the abyss of memory loss and, worse, the destruction of their identities as fully functioning human beings. As the author poignantly reveals, the most horrific devastation falls on the surviving adult children, who serve as daily caretakers and who witness the inexorable deterioration of their parents’ condition.

The author documents the process in painful detail. She describes the moves from the dementia wing of one assisted living facility to another facility better equipped to treat people with advanced dementia. She also describes the various medications she and her siblings tried for their mother, and the frustrating bewilderment that her mother increasingly experienced. Above all, Farrow describes her own complex, even conflicted emotions until the moment of her mother’s death.

This story would be valuable even as a stand-alone narrative. It is vital to understand this agonizing process because it is so common and will inevitably increase as the population ages in the United States. This part of “The Logbooks,” perhaps, is even more useful for readers who have yet to experience the emotional and other burdens of living with aging relatives and friends struggling with dementia.

Farrow’s inclusion of her mother’s dementia in her book, however, goes far beyond a personal story alone. It is inextricably linked to the broader theme: memory and history. By addressing her mother’s loss of memory, and thus the loss of her personal identity, the author encourages her readers to move from the micro to the macro. The achingly human consequences of dementia transform memory and history from an abstraction into something powerfully human and concrete. By juxtaposing her mother’s story with the logbooks of Dudley Saltonstall, she underscores her central premise: Americans still fundamentally lack a meaningful memory of a slave labor system that held millions of people in savage bondage.

The implications are both staggering and depressing. This historical amnesia means that slavery is barely taught and largely dismissed as an unfortunate aberration in an otherwise magnificent story of economic, political and military triumph. With a few conspicuous exceptions, the tragic human dimensions of slavery receive scant mention in the major educational, media and entertainment institutions.

This black invisibility has severe consequences that have endured for centuries in America. Because black Africans were items of commerce and not human beings with feelings, hopes, aspirations and sorrows, that mindset became institutionalized among white Americans and it never fully dissipated. As Farrow perceptively notes, there is a link between that ugly reality and the incontrovertible fact that African-Americans generally have poorer educational, economic and housing opportunities, inadequate health care, and suffer many other institutional barriers to full equality. These all reflect the power of memory and the impact of its loss.

Even more recently, Americans and the world have seen the dramatic effect when the majority society views its residents of African descent as somehow lesser human beings — even when this perception is barely conscious. The disgraceful pattern of police racial profiling, often resulting in humiliation and even killings in New York, Oakland and Ferguson, Mo., emerges when white officers see themselves as armed occupiers rather than as community protectors. The underlying attitudes reflect the same contempt about black people that Saltonstall expressed in his logbooks. This book is one valuable antidote to that historical tragedy. Much more, of course, is needed.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.