The Homeless and the Indigent Are People, Too

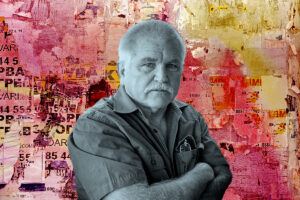

A powerful new play at Hollywood's Hudson Guild Theater explores the lives of some of our most neglected and misunderstood communities. Robert Galinsky stars in "The Bench" at Hollywood's Hudson Guild Theater.

Robert Galinsky stars in "The Bench" at Hollywood's Hudson Guild Theater.

When actor-writer Robert Galinsky moved to New York City as a young man from Hartford, Conn., he lived in a rent-controlled apartment in the East Village. Recognizing he would not have to work himself to exhaustion every month to make rent, he decided to dedicate his time to helping the underprivileged, volunteering locally at Trinity Homeless Services and at The Stella for the formerly homeless in Spanish Harlem.

He eventually wound up teaching literature to the incarcerated on Riker’s Island after meeting former Black Panther Jamal Joseph, who founded the youth-oriented IMPACT Repertory Theatre in Harlem. And it is this experience that serves as the inspiration for his one-man production, “The Bench,” which makes its debut this week at Hollywood’s Hudson Guild Theater.

“I tuned in and heard their beautiful vulgar poetry and also learned that they weren’t just aliens and ghosts and zombies with no roots,” Galinsky tells Truthdig. “They were people who had roots right there on those benches, had communities and had mores and their own little culture. And it just blew my mind. They were dealing with the same emotional issues of people who had homes, people who had families and structures behind them.”

Set in the late 1980s amid the AIDS epidemic, the play stars Galinsky as five different characters, sometimes interacting with one another, other times decrying their fate to whoever will listen. Produced by Chris Noth of “Sex & the City” fame and directed by Jay O. Sanders, it ran for roughly 30 weeks off-Broadway in 2017 at the Cherry Lane Theater and the East Village Playhouse to glowing reviews. The play’s new venue coincides with Galinsky’s own move to L.A., where he’s shopping his concept to TV producers when he’s not volunteering at the Downtown Women’s Center.

“Interacting on benches late at night under sometimes risky conditions, shitty weather, I became friends with these guys. One of them actually asked me if I wanted to borrow two bucks,” he says of his experience in writing “The Bench,” which included workshopping the play in front of his students on Riker’s Island.

On two separate occasions, Galinsky found himself in a fistfight. An especially close call came early on when he was discovered recording some of the inmates as part of his research. “You a cop?!” one of them yelled in his face, while Galinsky attempted to explain himself.

“You’re investigating how we do what we do, and you want to tell people?!”

“Yeah,” he replied.

“OK, fine,” was the response. He was left alone after that.

Jamal Joseph, Galinsky’s mentor and a member of the Panther 21, had a similar experience when he was arrested, accused of plotting bomb and long-range rifle attacks on New York City police in a case that later collapsed. Just a teen at the time, he served six years in Leavenworth, where he earned two college degrees in the 1960s. Joseph also wrote a play for Black History Month, and was startled to see numerous Latino prisoners turn up to watch his all-black cast rehearse.

“Your first reaction is, man, who they mad at?” recalls Joseph, a 2008 Best Song Oscar nominee for his work on the documentary “Raise Up: The World Is Our Gym” (2017). “These brothers don’t usually leave their area of the yard unless they have a beef with somebody. Finally, after about 10 or 15 minutes, one of the guys came over to me and was, like, yo brother, I don’t mean to get in your business, but that guy you’re working with, I’m not feeling his character, homes. And I was like, why don’t you do it? And he was great, and he made his friend get in. So, I went back and I added some Latino characters. And then some of the white brothers got nervous, and they were like ‘a couple of times week these black dudes and Latino dudes sneak off someplace, let’s see what’s up.’ Then some of them jumped in.”

Joseph watched as the men responded to each other in a way he hadn’t seen before, leading to a drop in gang violence at the prison. The experience awoke in him the power of art to heal and unite, eventually leading to his co-founding IMPACT Theatre, where he helps at-risk youths transform themselves and their communities.

“Our country has never been truly about growing up to be social changemakers, or seek justice for people,” says Galinsky. “Our country has always been about seeking a lawn and picket fence and property, so we can stay safe. And I think with all of the sharing all over the globe, it’s become more fashionable, more acceptable to take on the role of sharing responsibilities for our earth and our relationships.”

A demographic shift among young people bears his thesis out, as recent polling finds 55 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 prefer socialism to capitalism. Joseph points to a few groups throughout our nation’s history who saw their protests blossom into social movements—abolition, the end of child labor, opposition to the Vietnam War and the push for civil and LGBTQ rights.

“Ten years ago, people would say young people are complacent, they don’t get it,” he observes. “We have a real generation of young activists now who are sophisticated, who are smart, who understand that the problems are systemic. Sometimes people come to an awareness thinking it’s one bad cop or one racist store owner. Then you begin to hang out with other young people and they begin showing you how police brutality and racism and classism are institutionalized, and we have to fight those institutions.”

At Riker’s Island, Galinsky is battling a system he believes is set up to maintain or increase recidivism in order to feed the prison industrial complex. The odds are simply not in former inmates’ favor. While writing “The Bench,” Galinsky wrestled with how best to awaken the public to this crisis, which is why he wants to take his show to television.

“Here’s a man who genuinely loves people, people from all backgrounds, incarcerated folks, formerly incarcerated folks, and homeless folks,” offers Joseph. “It shows up in everything he does and especially in this amazing piece, ‘The Bench.’ “

Unlike most New Yorkers, who have learned to block out the people they see sleeping on benches, Joseph and his colleagues at IMPACT often stop and introduce themselves, exchanging a few words and even buying their new acquaintances a sandwich if they think a few dollars might go toward drugs or alcohol instead. What he and Galinsky have learned is that human interaction can often go a long way toward healing.

“This is something I’ve been dealing with and doing my entire life,” says Galinsky. “Sometimes eye contact is better than a piece of bread or a dollar bill.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.