The Disappeared: MS-13 Violence

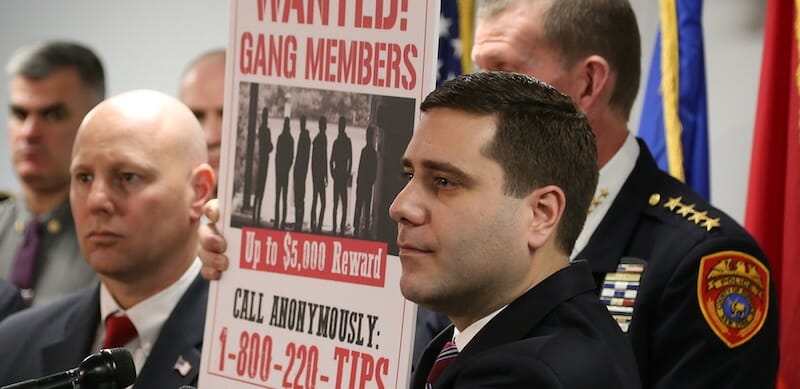

Police on Long Island wrote off missing immigrant teens as runaways. One mother knew better—and searched MS-13’s killing fields for answers. Timothy Sini (at right), who was Suffolk County, N.Y., police commissioner when Miguel Garcia Moran went missing, said police suspected Moran had been murdered—even though they listed him as a runaway. (Photo: Suffolk County District Attorney)

Timothy Sini (at right), who was Suffolk County, N.Y., police commissioner when Miguel Garcia Moran went missing, said police suspected Moran had been murdered—even though they listed him as a runaway. (Photo: Suffolk County District Attorney)

The string of text messages that would come to haunt Carlota Moran seemed like just an annoyance at first — an interruption to what was supposed to be a special outing for her and her son. It was the school break after Presidents Day in 2016, and Carlota had taken 15-year-old Miguel to the mall for a long-promised lunch at the Chinese buffet. Miguel walked with his arm slung around his mother’s shoulders as they returned a pair of pants at American Eagle.

Every few minutes, Miguel’s phone pinged with messages, distracting him. Carlota asked who kept texting him and he answered, with teenage vagueness, “Just a boy from school.”

Carlota was just over 5 feet, with thick black hair that fell midway down her back. At 5-foot-10, Miguel towered over her. As he tried on clothes in the dressing room, he teased her, “Why did you make me so handsome?”

The messages kept coming. They were from Alexander, a classmate of Miguel’s at Brentwood High on Long Island, and promised a taste of cool on a dull and frigid February afternoon. “Hey, let’s smoke up today,” Alexander wrote on Facebook Messenger.

“No way. You’re so bad — what did you do?” Miguel responded.

Miguel eventually agreed to join him, but not until later, and he wanted to bring a friend. “No, only us,” came the response. “We’ll get the blunts. That man Jairo is going to treat you. But just you, dog. I can pick you up and bring you here with us. But just us.”

After lunch, Carlota dropped Miguel at a neighbor’s to play video games, calling out to be careful as he jumped out of the car and ran across the quiet street. A man had recently been found dead in the woods, and she was worried.

Miguel and Alexander switched to Facebook voice messages. “Should I wait for you in the woods?” said Alexander, whose Facebook handle was Alexander Lokote, Spanish slang for “Homeboy.”

“No, better at my house — I don’t like to go out there in the trees,” Miguel said, pressing the phone close to his mouth to be heard over the video game music.

As night fell, Miguel and Alexander argued about whether to meet at Miguel’s house or in the woods that stretch like connective tissue through the small towns of Long Island. Around 7 p.m., Miguel agreed to go to the patch of trees nearest his home, by the high school. He said he couldn’t stay long.

“Where are you? I’m here with Jairo. Should we pick you up?” Alexander said.

“Wait by the school,” Miguel replied.

“OK, come over. We’re just getting here now, by the fluorescent lights.”

Miguel walked off toward the woods wearing a pair of black sweatpants and vanished into the darkness. The only clue his family would have to where he had gone and what awaited him there were the 84 Facebook messages he had exchanged that day with Alexander. They were discovered, weeks later, by his teenage sister — not the police.

Miguel was the first of 11 high schoolers to go missing in a single Long Island county in 2016 and 2017, as the street gang MS-13 preyed with increasing brutality on the Latino community. As student after student disappeared, often lured out with the promise of smoking blunts in the woods, their immigrant families were stymied by the inaction and inadequate procedures of the Suffolk County police, according to more than 100 interviews and thousands of pages of police reports, court records and documents obtained through freedom-of-information requests.

Many of the families came from countries where officials have historically looked the other way as gangs and death squads disappear young people. Now they felt the same pattern was playing out again, in the woods of Long Island. The officers they asked for help dismissed their children as runaways instead of crime victims, and they repeatedly failed to provide interpreters for witnesses and parents who only spoke Spanish. Their experience points to a larger breakdown between the Police Department and Latino immigrants. Too often, Suffolk detectives acknowledge, police have stereotyped young immigrants as gang members and minimized violence against them as “misdemeanor murder.”

Today, Suffolk police and the FBI are cracking down on MS-13. They’ve charged dozens of MS-13 members with felonies, and the disappearances have mostly stopped. President Donald Trump visited Long Island and praised Suffolk County police for doing a “spectacular job” against the gang, which he has made a national security priority. The Police Department says it took the disappearances seriously and has improved relations with the Latino community. But Suffolk police gang squad head Lt. Tom Zagajeski acknowledged that, before the surge of national attention, the department’s efforts to fight MS-13 and understand its connection to the wave of disappearances fell short. “I think we’re a little more aware of things we didn’t pay that much attention to,” he said in an interview.

For Miguel’s family and many others terrorized by MS-13, the police response came too late, and remains too little.

Carlota had been trying to protect Miguel since before he was born. When doctors in Ecuador said there was a problem with her placenta, she lay in bed for months. When her tiny baby arrived at 29 weeks, she slept next to his incubator. Once he learned to walk, Miguel’s favorite game was to stand outside the front door and wait for Carlota to come looking for him. Then he’d tear down the street, giggling, glancing over his shoulder to make sure she was following. For a while, Carlota indulged him. She didn’t want him to be scared of going outside. But when he turned 4, she put up a chicken wire fence.

She felt the pressure of being his sole defender; his father had left after he was born. As he grew older, her family chided her for sheltering him. Kids teased Miguel for being chubby, for his slight stutter and for holding his mother’s hand long into elementary school. Carlota married an Ecuadorian who lived part of the year on Long Island and then got green cards for Miguel and his big sister, Lady, in 2014. The marriage didn’t last, but she made ends meet with her assembly line job at an envelope factory. She and her kids lived in a two-bedroom apartment in the majority-Latino town of Brentwood, midway between Manhattan and the Hamptons. It felt to Carlota like both were almost within reach.

By 2016, Miguel and Lady were both enrolled at Brentwood High, and once again, Miguel was being teased. Carlota could see how desperate he was to fit in. He bleached his hair blond; she made him dye it brown again. He tried to pierce his ears; Carlota put a stop to it. She scolded him when he got her name tattooed on his arm, but also felt flattered.

Lady, a year ahead of Miguel, brushed up against the gangs first. Boys wearing the blue plastic rosaries favored by MS-13 had pestered Lady to sit with them at lunch and smoke marijuana after class. When she turned down MS-13’s invitation, members bullied her and knocked her down in the halls. But Lady, who has long, thick hair like Carlota and a habit of narrowing her eyes when she talks, was a natural loner and determined to become a nurse. After a few months, the gang gave up. She worried that her soft little brother, a mama’s boy who still collected Beanie Babies and watched Disney cartoons, would be an easier target. In a special education evaluation, a Brentwood administrator described Miguel as “eager to please” and in need of more “positive peer interactions.” Lady warned him that there could be consequences for acknowledging the wrong people, or spending too much time in the “papi hallway,” where immigrant students hung out. “I told him, ‘This is how you survive high school: Do not make friends with anyone,’” Lady said.

Carlota had heard about the gang problems at Brentwood High. She made a habit of smelling Miguel’s clothes for marijuana. But when he mentioned that some classmates were hassling him, she gave standard parent advice to ignore the bullies. She was happy when Miguel started going to meet friends by the high school. She loved how confident he was becoming. He was lifting weights and was supposed to start speech therapy for his stutter. He had a girlfriend and got along well with Carlota’s boyfriend, Abraham Chaparro, who he called his stepfather. On the Friday he went missing, he had put in an application to work with Brentwood’s volunteer fire department.

Carlota knew it was good for Miguel to become more independent, but still she was pleased that he wanted to spend part of his winter break with her. After she dropped him off to play video games, she picked up chicken and rice for the family’s dinner. When she got home, she texted Miguel to ask where he was. An hour passed and she texted again. She sent a third, a fourth, a fifth message, each time telling herself that he hadn’t heard the first few dings. “Miguel, where are you?” “Miguel, please come home. Nothing will happen.”

By midnight, her stomach was clenched with dread. Miguel never went more than a few hours without calling her. He never missed his 10 o’clock curfew. By 2 a.m., she couldn’t wait any longer. She got in the car and started driving, to the high school, the public soccer fields, to bars that Miguel was too young to get into. Her mind ran wild with visions of him dangling out of a crumpled car or lying unconscious at a party. “I was looking and looking, and the hours were passing so slowly. I was all alone in the dark out there, and it felt like my world was ending. I was so scared I would never see my boy again,” she told me.

When she ran out of places to look, Carlota came home and paced in front of the house, peering into the darkness. Then, she sat fully clothed on her bed, waiting for the sun to come up so she could go to the police station and report Miguel missing.

The door to the station was locked, so Carlota rang to be buzzed in. Sleigh bells taped to the door jingled as she opened it. Officers sat on an elevated platform next to a glass case of vintage toy police cars. An officer drinking coffee greeted Carlota and asked what he could do for her.

Responsible for half of Long Island, Suffolk County’s Police Department is the 11th largest in the country but has struggled to adjust to an influx of Latino immigrants. The station faced a Latino storefront church, a Central American grocery and a pupusa restaurant, but few detectives there spoke Spanish, and none were certified as bilingual.

Carlota didn’t know much English, so she brought along her boyfriend, Abraham. She gave the basic details for the police report — Miguel had brown eyes, weighed 235 pounds, was 15 years old — and tried to explain that her son would never run off like this; he was so attached to her, he couldn’t even handle sleepovers. The officer told Abraham there was no reason to panic. Most likely, Miguel was still with his new high school friends. “They’re probably hanging out in New York City,” Abraham remembers the officer saying. They should go home and wait for Miguel to come back.

There’s a truism in law enforcement that the first 24 hours are the only 24 hours. The New York City Police Department has a checklist of dozens of things officers must do right away if a minor goes missing, including speaking with the kid’s friends, checking their social media accounts and putting out a press release. Nassau County, which borders Suffolk, has an even more extensive protocol that includes alerting state officials within two hours of taking a report. The Suffolk County police handbook requires just one step if a child is reported missing: Search the area.

When they got home, Carlota was beside herself. Lady and Abraham spent the day inventing scenarios to reassure her, and themselves. They went to talk with Miguel’s friends, but no one knew anything. If police thought Miguel had been abducted and was in danger, they could have asked for a statewide alert that would have notified people through text messages and social media to look out for him. That evening, Carlota and Lady waited for their phones to ding with an alert. But state records show the Police Department never made the request.

The next day was Sunday. Lady and a friend searched the woods, with a pet dog for protection. Venturing deep among the bare trees, they found dirty clothes and mattresses surrounded by condom wrappers, but no sign of Miguel. Carlota went through his things, looking for some clue and instead finding his notepad filled with drawings he had made of their family. She talked in circles about where Miguel might have gone, always coming back to the conclusion that someone must have kidnapped him. As worried about Carlota as about Miguel, Abraham did not leave her side.

A Spanish-speaking detective was assigned to the case. A bodybuilder with a full sleeve of tattoos, Detective Luis Perez had served in the Air Force before joining the Police Department in the 1990s. He led other officers in searching the area around the house under the low winter sky. Officers also looked through Miguel’s room and talked to a neighbor who said that he had seen Miguel walk off toward the high school, but they didn’t know anything more. Perez told Carlota not to worry, Miguel would be back soon.

When classes started again on Monday, Lady worried about leaving her mother alone, but Carlota insisted she go to school. Carlota stayed home and made a list of places in Brentwood and neighboring towns where Miguel might be. When Abraham got off work, they drove around together, scanning the streets.

Three days had passed since Miguel went missing, and police now sent out a press release. It said, “Detectives do not believe there is foul play involved.” The department listed Miguel as a runaway in the state missing person database, even though a spokesman said department policy is to assume missing children are in danger unless they have been thrown out by their parents or have a history of leaving home. Police generally spend less time and resources looking for teenagers who leave home voluntarily. “As soon as you use the word ‘runaway,’ it’s a non-incident. It’s a non-crime,” said Vernon Geberth, a former New York City homicide detective who wrote a widely used police investigative textbook.

On Tuesday, someone started responding to the text messages Lady had been sending to Miguel’s phone.

“Who are you?” the message said.

“I’m Miguel’s sister. Why do you have his phone?” Lady wrote back, shaken but also relieved that someone might finally know where Miguel was.

“Send me a photo of you to see if I know you,” came the response. Lady wondered if her brother’s captor was playing with her. But she still sent a photo of herself with Miguel. She says she went to the station and told Perez about the strange request, but he didn’t ask for her phone, and then the messages stopped.

Perez and the Police Department declined to comment on Miguel’s case. The department also declined to provide the missing person report to me or Miguel’s family, citing an open investigation. The department said that it conducts every missing-person investigation thoroughly and follows up on all leads.

“Our response to a reported missing person does not differ based on nationality,” it said, later adding, “Suffolk County Police officers are among the finest in the country and treat everyone with professionalism and compassion.”

Carlota started watching the news obsessively, and MS-13 kept coming up. Founded in Los Angeles by Central American refugees in the 1980s, MS-13 is relatively small nationwide but has been active for years on Long Island. The gang had killed two people around Brentwood during the first two months of 2016 and staged a shootout at the town library.

After five days of no apparent progress from the police, Carlota decided she needed a new strategy. She got a local Spanish-language TV reporter to film a segment about the case. Her face shiny with tears, she confessed the possibility she had begun playing and replaying in her mind: “There’s so much you can never be sure of in this country. What I fear most is, it could be the gangs.” Reporter Alex Roland nodded sympathetically but later told me he thought Miguel had probably run away. After all, he explained, that’s what the police said.

The department hadn’t made a missing poster for Miguel, so Carlota photocopied his freshman ID and wrote next to it in Spanish, “If anyone sees this boy, please call his mother.” She posted the flyer at delis, churches and Miguel’s favorite clothing stores. Tips started to flow in: Miguel was eating empanadas, walking on the beach, begging outside the 7-11, getting a haircut at the barbershop. Each tip spurred an agonizing cycle of emotions: hurt and confusion that Miguel hadn’t let her know he was safe, then desperate hope, and finally, crashing despair as the leads turned out to be false.

Lady kept going to class and tried to keep it together for Carlota’s sake. But she really missed her brother. At night, she would replay his old messages to her, just to hear his low, hesitating voice. Then, in early April 2016, almost two months after he went missing, Lady discovered Miguel had left his Facebook account logged in on Abraham’s phone.

She started going systematically through messages from the past year. In one conversation, Miguel talked about saving up for Nike Cortez sneakers, but he abandoned the idea after a friend warned him that they were a sign of MS-13 membership. Most of his messages were failed attempts to talk to high school girls. Then, on the day he went missing, just one conversation — the 84 text and voice messages with Alexander. Lady said she recognized Alexander as a gang member from the language he used and the pictures on his Facebook page of grim reapers and laughing clowns — favorite memes of MS-13. There were strings of messages from anxious family and friends in the weeks that followed, but Alexander never sent another message after that night.

Carlota and Abraham say they went to Perez with the phone immediately. He kept it for a few days, and then he called and invited them to the high school to speak with Alexander. Experts on police procedure say a step like this is unusual and risky, because this kind of contact between a witness and a victim’s family could invalidate evidence in court. If Perez suspected foul play, they said, he should have gotten a warrant to search Alexander’s phone.

Assistant principal Lisa Rodriguez called Lady out of class over the intercom and had her wait outside the principal’s office as the adults talked to the student who had coaxed Miguel out. Alexander was dressed like an MS-13 member, with a blue plastic rosary and a long white T-shirt, but he looked like a child to Abraham, scared and “too weak to break a plate.”

Carlota and Abraham recall Alexander saying he and his friends had planned to go with Miguel to some train tracks, but Miguel never showed up. Carlota started crying. She demanded to be told where her son was. Alexander said he didn’t know. After half an hour, Perez dismissed him. “I knew right away this was something key, and I was begging Perez to press for more,” Carlota said. “I was telling them, ‘He has to know where my baby is.’” After they dismissed Alexander, Perez and the assistant principal told Carlota they thought he knew more than he let on, but there was not much officials could do about it.

A spokesman for the Brentwood schools declined to discuss the meeting but said the district fully cooperates with police. Rodriguez said she couldn’t remember who Alexander was. “I work with a lot of kids, it’s a large building, so I can’t even tell you,” she said.

After this meeting, Lady stopped seeing Alexander in school. The gang problem was getting worse. There were frequent fights in the hallways, and teachers shut themselves inside their classrooms. “These groups of students would all crowd around. It was scary,” bilingual education teacher Will Cuba said. Lady tried to ask around about Miguel without drawing attention. Students told her that MS-13 might have targeted him because one of his friends dressed in black, a sign of belonging to its chief rival, the 18th Street gang. But the friend told Lady he wasn’t affiliated with gang.

At the end of April, police asked the state for a missing person poster. It said, “Miguel is a runaway.”

Carlota stopped working at the envelope factory and fell into a routine of watching the news, paging through mystery thrillers at the library, asking Perez for updates and making the rounds of places where she had already searched for Miguel more times than she could count. Unable to sleep at night or sit still during the day, she began taking strong pain pills. She thought about counseling but dreaded the likely advice: that she needed to accept that Miguel might be gone.

It was the height of spring — three months since Miguel had gone missing — when Carlota saw something on TV that brought her up short: Another mother, crying over a missing son. Oscar Acosta was weeks away from graduating high school when he left home to play soccer on a Friday afternoon and never came back. He had told his mother a gang was bothering him because he had refused to join. “Something is terribly wrong. He didn’t take any clothes or money or anything,” the woman said. Carlota needed to talk to her.

A nephew of Abraham’s recognized the mother’s house on TV; it was just around the corner from the Applebee’s. Carlota knocked on the door that night, heart hammering.

The mother, Maria Arias, didn’t speak English. She told Carlota a familiar story: Detectives had reassured her that her son was hanging out with friends and would return after the weekend. Since then, Carlota recalled, Maria said she had been going to the police station for updates and leaving without information because of the language barrier. Maria later told me that she had to enlist a woman from church to help her report Oscar missing.

It was a frustration immigrants in Suffolk County have grappled with for years. Most Brentwood residents speak Spanish as their first language. But in 2016, only three people in the entire 3,800-person Suffolk County Police Department had passed a language test to interpret for Spanish speakers. One lawyer, Ala Amoachi, told me that she represented a Spanish-speaking Suffolk County woman who called police to report that her husband had been hitting her. When police came to the home, they used the abusive husband to interpret for his wife. The department declined to comment on this case, but it said it now has 10 certified interpreters. The New York City Police Department — 14 times as big as Suffolk’s — has 250 times as many certified interpreters. The Suffolk Police Department is one of the best paid in the country. Most detectives, including Perez, make more than $200,000 a year. But unlike a majority of big U.S. police departments, Suffolk does not give officers any extra pay for knowing a second language.

The U.S. Department of Justice has been supervising the Police Department since 2011, after white teenagers went “beaner-hopping” — their term for beating up immigrants — and killed a man from Ecuador. Police had failed to follow up on earlier reports that this group of teenagers was attacking immigrants, which the Justice Department said was part of a pattern of discrimination. It said Suffolk officers were both over- and under-policing Latino residents — stopping them more frequently than white people for minor violations, while also failing to fully look into the crimes they reported. This past March, the Justice Department found that Suffolk County officers, after seven years, are still not consistently using professional interpreters.

The Justice Department has also faulted Suffolk police for not doing enough to protect Latino teenagers from gangs. The Police Department pulled back from a joint Long Island FBI gang task force in 2012 amid a political squabble. Current and former Suffolk detectives told me they didn’t see MS-13 as a public safety threat, because its victims are usually at least on the fringe of gang life. They have a phrase for these killings: “misdemeanor murder.”

“When we see a missing Hispanic kid, we tend to assume it’s a gang-involved thing,” said Ken Bombace, who investigated MS-13 murders as a Suffolk County detective before leaving the department three years ago. “The sense is that these kids are killing each other.”

In June 2016, a third immigrant teenager went missing. His mother, Sara Hernandez, said she had pulled him out of Brentwood High because MS-13 was bullying him there. One afternoon, a group of boys came to the house looking for him, and he hid in his room. Then another afternoon, he did go, and didn’t return. Because nobody spoke Spanish at the police station, Sara had to pay her cab driver to interpret. He kept the clock running and charged her $70. She said police told her that her son could be hanging out with friends and would soon return, the same assurance they had given Oscar’s mother and Carlota.

Through the summer, Carlota struggled to maintain her belief that Miguel was alive but just couldn’t call home. The rare moments when she let herself imagine that he might be dead felt like a betrayal, as if she was killing him. Hoping to find a piece of his clothing or some other hint, she took to walking at dusk through an area of shaggy oak and pine trees that police called “the killing fields” because it was an MS-13 hangout and dumping ground for bodies. She saw old couches and television sets and a discarded speedboat. At the heart of these woods loomed a boarded up brick building. An abandoned psychiatric hospital. Carlota was spooked by the empty spray paint cans and candy wrappers in the brush and wondered who had left them there. But she found the loud crickets, the earthy smell and the murmur of traffic soothing, even hypnotic. “It was as if I was pulled in by some desperation. There was one night that Abraham called out to me because I was getting lost in there. But I wanted to just keep going deeper and deeper. It was like the forest was calling to me,” she said.

She was always sure to leave by nightfall. “For the first time in my life, I was afraid of the dark.”

Carlotta continued to check in with Perez weekly. One day, he invited the whole family to the station. As she walked through the lobby, Carlota did not see any safety advisories or missing person posters. At the front desk, police had laid out packets in English and Spanish to help people prepare flyers for lost pets.

The three of them sat down in a windowless detective room. Carlota hoped Perez was going to give them some news, but she also feared what it might be. Instead, the family said, he adopted a new attitude that caught them off guard. He accused them of knowing more than they were letting on. He spoke to Abraham in English, saying it was the language of the U.S., and had him interpret.

A different immigrant family that met with police in 2016 about gang threats toward their daughter secretly recorded their interaction with Perez after he was brought in to interpret between them and another detective. Perez is not a certified interpreter, and in the video, instead of speaking in Spanish, Perez asks the daughter if she is bilingual and, even as her father protests that he can’t understand, begins interrogating her in English. “You think we’re as dumb as the kids you hang out with? You think this is all a joke?” Perez says.

In their conversation with Perez, Carlota and Lady insisted that they didn’t know anything more. Carlota couldn’t understand why he would think she would keep anything back from the police that might help them find Miguel. What the detective said next stands out in the memories of all three family members. Perez turned to Carlota and told her, “If you’re so worried, go pay a fortune teller to find Miguel.”

After that, the department replaced Perez with a succession of three officers who seemed more compassionate but no more effective. Perez didn’t respond to the two dozen questions I emailed him. When I called him, he hung up. When I knocked on the door of his home in a gated community a few towns away from Brentwood, he told me to get off his property.

In August 2016, an 18-year-old immigrant was found dead in a park with machete marks all over his body. Carlota had always encouraged her children to spend time outside. Now, when Lady made plans to see friends or go to church, Carlota pleaded with her to stay home. Struggling to function on her own, she moved into Abraham’s basement apartment and brought Lady with her. “She was in so much pain because she didn’t know anything and the police never called her,” Abraham said. “I thought Miguelito must be lying dead somewhere, but of course I would never have suggested that to her.”

By September, Carlota rarely left home. Some days she was relieved there was nothing on the news about Miguel’s case, and other days she felt desperate for any resolution, no matter what. Lady sent Facebook messages to Miguel every few weeks. “We love you.” “Please come back, mami is really suffering.” “Baby brother, I miss you.” MS-13 members were again targeting Lady at school, threatening that if she didn’t join them, she could be next to disappear. She urged her mother to do something to pull police attention back to the case. So Carlota tracked down a new Univision reporter.

He agreed to tape a segment outside the high school. He asked Carlota where she thought her son might be, but as she was answering, the producer cut in. Two girls from Brentwood High, Kayla Cuevas and Nisa Mickens, had been attacked as they walked near their homes. Nisa had been killed in the street. Kayla ran into a patch of woods and was missing overnight. Police told state officials she was a runaway. Now her body had been found.

Carlota followed the reporter to the crime scene. Police cars with flashing lights blocked the street. Carlota saw a woman crying in the middle of the road. “I was like, ‘First Miguel, and now these two girls? What is happening in this town?’ I felt this panic rising up and I tried to make myself stop thinking,” Carlota said.

This case was different than the ones before. The victims were native-born U.S. citizens, girls, and the gang hadn’t even tried to hide their bodies. Their parents had nice homes and professional jobs, and spoke English. “Two high school girls killed by MS-13?” said Suffolk County lawmaker and former gang detective Rob Trotta. “That’s not misdemeanor murder.”

The murders made national news. Trump hailed the girls’ parents and invited them to his State of the Union speech. The Suffolk County Police Department came under intense pressure to solve the case. It posted signs offering a $15,000 reward for help catching the killers. Officers went door-to-door asking for tips. Over the summer, Suffolk officials had rejected an offer to start an anti-gang program for immigrant teenagers in Brentwood, according to two people familiar with the episode. Now, they called the organizer back and asked how soon she could get it running. Police arrested dozens of suspected MS-13 members and mapped out the local cliques. Within days, they were searching the woods with German Shepherds and shovels.

Zagajeski, the Suffolk gang squad head, said the girls’ murders spurred police to pay more attention to reports of missing Latino teenagers. “Where in the past we may have been like, ‘Oh, a missing girl, we hear this all the time,’ now it’s like, ‘Oh, a missing girl in Brentwood? There’s a lot of gang members over there, let’s take a ride over and see what it is,’” he told me.

In the days after the double murder, Carlota and Abraham returned to the crime scene and spoke to the woman they had seen crying in the street, Kayla Cuevas’ mother. They told her about Miguel, and she gave Carlota a rosary as a gesture of solidarity. A detective working with the FBI gang task force came to see Carlota at home. He vowed to quit his job if he couldn’t find Miguel, now missing for seven months. He took a swab of her DNA and showed Lady a photo of a teenager whom she identified as Alexander, the boy from the Facebook messages.

On Sept. 21, 2016, one week after the girls were murdered, Lady was watching coverage of the hunt for their killers when an alert flashed. Police were identifying a body found days earlier in the woods as missing high school student Oscar Acosta. Carlota raced in from her bedroom and saw footage of police walking along the edge of the same killing fields she had searched with Abraham. Then the announcer said a second body had been discovered. Carlota noticed two men in suits walking down the stairs to her door. Her legs began to wobble. They were from the FBI and had brought an interpreter to tell Carlota what she had already figured out from the TV: The second body was Miguel’s.

She fell to the floor, raking the tiles with her hands. Then she saw Abraham coming back from a job installing insulation and ran out of the apartment toward him. But she fell again and tumbled down the stairs. Abraham hesitated to cradle her, because his work clothes were covered in fiberglass. Two days later, Carlota woke up in a hospital bed. The trauma staff had written on her chart, “Altered mental state. Unable to answer questions. Patient repeatedly stating ‘Just kill me. My son, my son.’”

She spent the days in the hospital cursing herself for bringing Miguel to a place where he could be targeted by gangs. She remembered telling him to ignore the kids bothering him at school. Had she been too dismissive? A mantra looped in her head, “I want to die.”

Perez called Abraham to say he was sorry for the family’s loss. Soon after Carlota was released from the hospital, the body of the third missing Brentwood High student was found. He, too, had been buried in the killing fields.

In all the months of uncertainty, Miguel’s clothes and stuffed animals had comforted Carlota. They smelled like him and seemed like a vital connection to someone still alive. Now she packed them into five trash bags and put them on the street next to piles of fall leaves.

The coroner listed the cause of Miguel’s death as a blow to the head and his place of death as an unidentified road. He had likely been killed the night he went missing, although it was hard to tell because his body had been decomposing so long only his bones remained. Carlota had wanted to bury him in a casket and give him a Catholic funeral. But police returned Miguel’s cremated remains in a small cardboard box. Abraham chose not to translate the forensic report that said the bones were crisscrossed with long machete marks.

The police were paying more attention now, but the slaughter continued. The discovery of Miguel’s bones brought the MS-13 body count in Suffolk County to 10. In October, another 15-year-old, Javier Castillo, vanished and was listed with the state as a runaway, only to be found buried in the woods a year later. A man beaten until his face was pulverized was left in the street. A bystander was shot at a deli. And still no one was charged with any of the murders. At the peak of the violence, MS-13 murders accounted for 40 percent of all Suffolk County homicides. Latino residents began avoiding the streets after dark.

In April 2017, the gang left four boys in a gruesome tableau in the woods, bringing the murder count to 18. The bodies were found by one of the victims’ families, who said they had flagged down a passing police officer and asked for help with the search, only to be told to file a report at the station.

Of the Suffolk County families who lost children to the gang during the rampage, nine have told me they felt ignored and disrespected at times by police. Most say they had to look for their kids themselves and struggled to communicate with police. At least four saw their children listed as runaways before their bodies were found.

“The police treated me like I just had some rebellious kid on my hands, and meanwhile I was living the worst year of my life,” said Santos Castillo, Javier’s father.

As the head of the Suffolk County Police Department from January 2016 until early this year, Timothy Sini was ultimately responsible for handling the crisis. But when I asked him about Miguel and the other teenagers who went missing in 2016, he got confused. He initially said that the boys had disappeared in 2015 — before he became commissioner. He also said that even though police had listed Miguel as a runaway, detectives had immediately suspected a homicide. Law enforcement experts told me that if police believed immigrant high school students were being targeted, they should have warned the community.

Sini acknowledged that police increased their efforts after the two girls were killed, seven months after Miguel disappeared. “If you want to criticize the Suffolk County Police Department for not doing enough against MS-13” before then, Sini said, “I suppose you can do that.”

He called the phrase “misdemeanor murder” offensive. “We need to do as much as possible to eradicate MS-13 and will continue to do that. Any victim that has been murdered or injured, that is a tragedy,” he said.

An ascendant Democrat in Trump country, Sini has now moved on to become Suffolk district attorney. He ran for the position on the slogan, “The man who took MS-13 down.” Sini said it has taken time to change the Police Department’s culture. The man who ran the department before Sini is in prison for beating up a suspect who stole a bag of dildos and porn from his unmarked police car.

One of Sini’s most important accomplishments as commissioner was reconciling with the FBI and sending detectives to its Long Island gang task force. With the task force in the lead, investigators began making progress against MS-13, and federal prosecutors have now indicted suspects in more than half of the murders. A majority of the people charged with masterminding the violence belonged to the MS-13 Sailors clique, the most powerful gang at Brentwood High. Some were 15- and 16-year-olds.

The wave of MS-13 violence has largely subsided. But Miguel’s case has stumped police. Even though Sini said police immediately suspected a homicide, his murder remains unsolved two and a half years later. Asked why, Sini said: “Are you seriously asking me that question? Law enforcement has done a tremendous job. They’ve put MS-13 on the run in Suffolk County. I mean, this is a ridiculous question.”

Carlota and Abraham no longer haunt the killing fields, but they’re still looking for clues. I tagged along this past winter when they dropped in on a hearing at the Long Island federal courthouse where all the Suffolk County MS-13 murders have been consolidated into one case.

In the wood-paneled courtroom, parents of victims greeted each other like old friends at church. Kayla’s parents waved Carlota over. When the accused killers were led in, Carlota was surprised by how childish they looked, with their sparse goatees and lanky limbs stretched by still-unfinished growth spurts. A woman in the audience lifted up a toddler in a pink coat, catching the eye of a defendant who grinned and waved back with handcuffed hands.

Kayla’s mother pointed out the leaders of the Sailors. One was 19-year-old Jairo Saenz. Prosecutors have charged him with six homicides, including the murders of the two girls and Oscar Acosta, whose body was found next to Miguel’s. Jairo has pleaded not guilty. The indictment says he marked his victims for death because he suspected them of associating with rival gangs. The method he is accused of using to kill Oscar mirrors what likely happened to Miguel. Accomplices invited Oscar to the woods by a school to smoke blunts. Then, according to the indictment, the Sailors attacked him, loaded him into a trunk, drove to the killing fields, slashed him to death and buried him in a shallow grave.

Carlota remembered Alexander’s messages to Miguel. He had kept talking about “Jairo.” Jairo was the one who was going to hook them up with blunts. Who wanted Miguel to come alone. The only one who got the teenage honorific “that man Jairo.” Squeezing Abraham’s hand in the gallery, Carlota sat up straight to see. Jairo looked more muscular than the other defendants, with long eyelashes. A row of girls mouthed messages of support as the prosecutor detailed his crimes. Jairo showed no reaction when the prosecutor said the government would be seeking the death penalty, but the girls gasped and murmured. A baby squeezed too hard by one of them started crying.

After the hearing, the parents talked among themselves in an empty hall. Picture windows looked out from the 10th floor onto the spreading Long Island woods where most of the violence had taken place. Another mother confided that police had refused to let her see her son’s body because it was too disfigured. Carlota urged Abraham to approach the prosecutors.

“I am the stepfather of Miguel, who was missing,” he said to one of them.

The prosecutor asked who Miguel was, and how long he had been gone. Then he left and returned with his chief, who led Carlota and Abraham into a small room. When they came out, they said the chief told them that Miguel’s case had been difficult to crack and was still under investigation. Prosecutors were waiting for someone to talk. As we left, a member of the FBI task force chimed in, telling Abraham to call his local police.

That isn’t always as easy as it sounds. One afternoon this summer, Abraham shuffled through his collection of worn business cards, trying the numbers of different detectives. The apartment remained a shrine to Miguel. Carlota kept the urn of his ashes on Lady’s nightstand, nestled among some of his beanie babies, several Bibles open to passages about fiery justice and a now-deflated Mylar balloon he bought for her for Valentine’s Day the week he disappeared. In the corner sat a fat folder of papers for her citizenship application; she couldn’t decide whether she wanted to become a citizen or return to Ecuador for good.

After half an hour, Abraham got through to the Suffolk County homicide detective who now has Miguel’s case and asked for an update. He put the call on speaker phone so I could hear.

“We’re still working on it, us and the FBI. We are still trying to find out what happened,” the detective said.

Abraham asked about Alexander. What was his full name? Had he gotten away?

“That was one of the kids who was spoken to. I’d have to look in the folder and see what his name is,” the detective answered. “Everybody that we had a name of, we spoke to, and they didn’t really provide any usable information. Unfortunately, sometimes these things take a long time.”

I decided to look for usable information myself. For months, I didn’t make much headway. Nobody I talked to could tell me Alexander’s full name, and he never came back to Brentwood High. I eventually spoke with two teenagers who said they had not been questioned about Miguel but knew who had killed him. They said it was “that man Jairo.”

Jairo, they and others told me, had come from El Salvador as a teenager. He worked construction jobs and lived in a large house with his mother, brother, three sisters and a pit bull. He hung out in the halls of Brentwood High but rarely went to class. Friendly and charming, he earned his gang nickname, “Funny.” Girls liked his dimples and strong cologne. He filled his social media accounts with selfies and photos of his infant daughter. In early 2016, he changed, telling gang underlings that he had to show he was hard or others would disrespect him. Jairo’s lawyers declined to make him available for an interview.

Henry, a Brentwood High MS-13 member who has given information to the police, told me the gang saw Miguel as overly friendly and effeminate. He also confused the Sailors. He didn’t seem to have gang friends, but he sometimes came to school wearing the red bandanna of the Bloods, the rosary of MS-13 or the head-to-toe black of the 18th Street Gang. Henry thought Miguel was just a nerd trying to look cool, but MS-13 members started circulating photos of him on a group text.

Henry said that at Jairo’s order, he grilled Miguel about how he dressed. Jairo listened in on speaker phone as Miguel said he didn’t owe anyone an explanation. And that was it. Miguel was marked for death because the Sailors felt he was disrespecting MS-13 by wearing the clothes of rival gangs. Henry said that after the Sailors killed Miguel, some members went back, unearthed the body, cut apart his limbs and swung a machete into his face. Around the time the gang was re-butchering Miguel’s body, Carlota was pleading on TV that her son was not a runaway.

Jairo’s ex-girlfriend, nicknamed Chinita, also linked him to the murder. A 14-year-old freshman when she started dating Jairo in 2015, Chinita at first thought he was sweet and liked that he could drive her to the movies and mall. Then he started becoming more possessive and sending her strange messages, and she took out a restraining order against him. Chinita said that, soon after Miguel disappeared, Jairo texted her that he was in the woods playing with human teeth. He sent her a photo of a dirty pair of black sweatpants like the ones Miguel wore the night he vanished.

In September 2016, right after Miguel’s body was found, police arrested Jairo for driving without a license. Officers let him go with a notice to appear in court, which he blew off. Less than two weeks later, Chinita’s parents filed a missing person report saying Jairo had taken her and stashed her at his house. Nevertheless, police listed her as a runaway. Her parents say they asked officers to search Jairo’s house, but they never did. Chinita escaped after two months and called her mother. Chinita says police refused to send a squad car and told her to take a taxi home. The FBI would later find the clique’s cache of guns, bats and machetes buried in the backyard.

By the fall of 2016, Jairo was the subject of a restraining order, had skipped a court appearance for the driving violation and had allegedly kidnapped a minor. And then, having already killed three people, not counting Miguel, he went on to kill at least three more, according to federal prosecutors.

The last time I went to see Carlota, she and Abraham were in the middle of looking for a new apartment. She had decided to stay on Long Island until someone was charged with Miguel’s murder, but she was hoping to move to Nassau County, which she calls the “American side” of Long Island. Carlota is feeling especially scared these days. Another immigrant teenager was murdered in Suffolk County over the summer. Kayla Cuevas’ mother was struck and killed earlier this month by an SUV at a memorial service for her daughter after getting into an argument with the driver.

When I told Carlota what I’d learned about Jairo, she shook her head and spoke angrily. How could a group of teenagers have committed so many murders, essentially becoming serial killers in the space of a year, when the clues were right there in those messages sent to her son during winter break?

“You get the sense that the police here have this attitude that we Latinos are just killing each other, and this is their country,” she said. “If Miguel was an American, they might have found him right away. If they’d investigated then and there, maybe all these other children wouldn’t have had to die.”

Even though they haven’t found a place yet, Carlota has packed up most of the apartment into boxes. She finally got rid of the bed Miguel slept on. The detectives’ cards she kept safe in a drawer, to avoid losing them in the mess of the move. When she’s ready to leave, she’ll pack them up last, just in case.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.