The Dam and the Bomb: An Appreciation of Cormac McCarthy

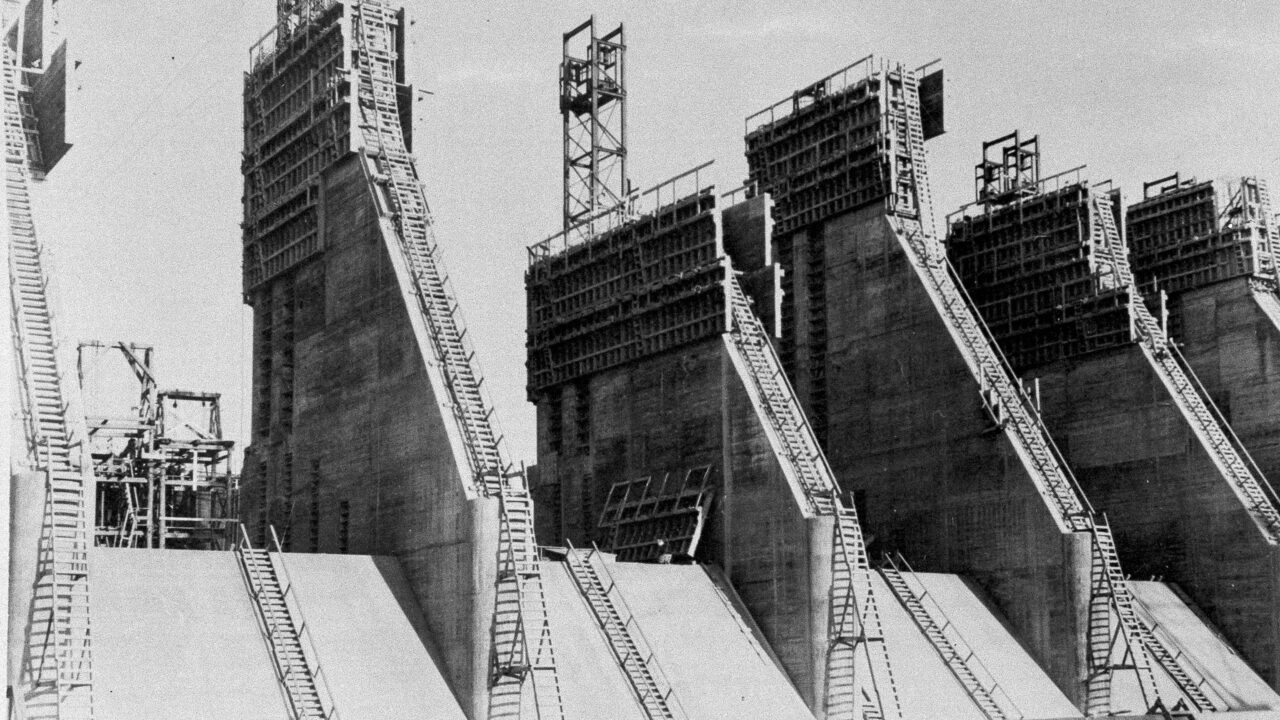

McCarthy and his characters inherited a world where the sum of all intellect proves fatal to its parts. Among the many New Deal agencies set up by Congress in its 100 Days session in 1933 were the Tennessee Valley Authority, which built dams like this one rising at Pickwick Landing, Tenn., in 1937, as part of the TVA program to control flooding and provide hydroelectric power. (AP Photo)

Among the many New Deal agencies set up by Congress in its 100 Days session in 1933 were the Tennessee Valley Authority, which built dams like this one rising at Pickwick Landing, Tenn., in 1937, as part of the TVA program to control flooding and provide hydroelectric power. (AP Photo)

In 1937, Cormac McCarthy’s father, Charles Joseph McCarthy, a Rhode Island trial attorney just a few years out of Yale Law, packed up his wife, young son, and the boy’s siblings, and drove from Newport down to Knoxville. He was taking a position with a new government organization called the Tennessee Valley Authority. “Those were depression days,” he explained in a late interview. “The salary was much more than I was making.”

One of the most famous legacies of the New Deal, the TVA was established in 1933 to electrify the South through a system of hydroelectric dams. But that infrastructure altered the landscape by flooding rivers, exacting a human price that is less well known. First, having chosen the site for their flood reservoir, the TVA notified residents that a dam was coming, sometimes giving only two weeks’ notice. Next, the government offered “fair market value” for the plot. Rarely did this fee compensate the cost of relocation, let alone the emotional loss of a homestead, farm, and graveyard. Last came force. Those who refused to sell had their property condemned in court, which is where McCarthy Senior came in.

One of the most famous legacies of the New Deal, the TVA was established in 1933 to electrify the South through a system of hydroelectric dams.

“Condemnation has many disadvantages,” he admitted in a 1949 journal article justifying the practice. “It is expensive and it takes away from the acquiring agency the determination of the amount to be paid. More important still, it is likely to leave a residue of ill will.” Roosevelt’s New Deal would bring many social amenities to the rural Southern poor, but in these first years, with the Confederacy still in living memory, suspicion clung to anything federal—in this case, with cause. Nevertheless, only 3 percent of all land obtained thanks to the efforts of the Rhode Island lawyer came through condemnation, as compared with voluntary sale. This, the elder McCarthy said, was because Roosevelt’s team stipulated in the TVA Act of 1933 that a judge, not a jury, would hear land suits brought against the organization—a loophole that kept locals from avenging their disgruntled neighbors with great and variable sums of money. While his superiors handled the bigger corporate suits that reached the Supreme Court, in district courts, wherever the next reservoirs were about to be flooded, Assistant General Counsel McCarthy oversaw the rest of that 3 percent: smaller suits, the kind brought by local families. Disadvantageous, he believed, but necessary. As he told his interviewer, “you’re looking at the best damn trial lawyer in the government service.”

* * *

This origin story found its reckoning in Cormac McCarthy’s final books, The Passenger and Stella Maris, two very timely, funny novels published in the months before his death. Where he used to describe a kind of primordial American past, McCarthy now peers through the thin curtain of the Cold War to weigh in on the Trump years: cryptocurrency (“And every transaction will be a matter of record. Forever”), transgender rights (he’s pro), the metaverse (which he calls, without elaborating, “the final abridgement of privilege”), conspiracy theories (the truth is out there, Lee Harvey Oswald was a pawn). These novels are also McCarthy’s richest. Where earlier he narrated each of his themes in tidy order—cars and cops in The Orchard Keeper (1965), horses and Spanish in his Border Trilogy (1992–98), parenting in The Road (2006)—he crams The Passenger and Stella Maris with every other interest you might imagine for a man of his roots and years: Formula Two racing, prewar Patek Phillipes, 1970s Maserati Boras, the Manhattan Project, bluegrass, JFK, aeronautics, Amati violins, animal taxonomy, psychotherapy, mathematics, quantum physics. A life’s deskwork scraped into a trunk.

But these books are also confessions, and confession is what McCarthy’s father has to do with it. Confession can free you: just ask the guilt-wracked veteran Sheriff Ed Tom Bell of No Country for Old Men. It can also set the record straight, as late-life memoirs are wont to do. Now the notoriously taciturn McCarthy wants both: these two books shed remarkably clear light on the moral concerns and aesthetic arc of his career, particularly his most philosophical works, Suttree (1979) and Blood Meridian (1985). For comfort, McCarthy sends The Passenger’s quiet loner Bobby Western. For the truth, he sends Bobby’s poor sister, Alicia.

These books are also confessions, and confession is what McCarthy’s father has to do with it.

In McCarthy’s novels, people commit terrible acts—necrophilia, infanticide, cannibalism—and often with reason. His villains are symbols of that dark reason: the trio of swampland marauders in Outer Dark (1968), the dream-curdling scalp-hunter in Blood Meridian, the frigid bounty hunter stalking No Country. In The Passenger and Stella Maris, McCarthy tops this rap sheet with his worst crime yet: nuclear Armageddon. And the perp is one of American history’s finest minds, the porkpie-hatted architect of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Though it isn’t Armageddon exactly. The Passenger is a historical novel set in 1980, and the world is still very much alive. The mere possibility of apocalypse by human means is crime enough. Throughout the novel, Bobby Western, a 36-year-old salvage diver and racecar driver, is haunted by his upbringing near the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, and in Los Alamos, New Mexico, two places where his physicist father, a protégé of Oppenheimer, helped design the device that would devastate Hiroshima in 1945. As we trail Bobby through the American South, the Midwest, Mexico, and Europe, we see the deep unsettlement of the atomic era in the mounting mysteries of his life: freak accidents, disappearances, detectives. “Shit that makes no sense,” as Bobby’s friend puts it. Or as another explains: “My understanding of it is not what makes it so.”

Above all the book is haunted by the ambiguous past of Bobby’s late father, whose papers have suddenly disappeared. Apparently the subject of a high-level investigation, these missing documents tease Bobby with what he should have asked about the physicist in life, and what it is now too late to learn. (The Japanese novelist Kenzaburo Oe, who died just a few months before McCarthy, also depicted a lost trove of paternal papers in Death by Water, another novel of nuclear dread published toward the end a similarly unsparing career.) Near the end, Bobby imagines the 1945 Trinity Test in New Mexico, where the first atomic bomb was exploded:

Two. One. Zero. Then the sudden whited meridian. Out there the rocks dissolving into a slag that pooled over the melting sands of the desert. Small creatures crouched aghast in that sudden and unholy day and then were no more. What appeared to be some vast violetcolored creature rising up out of the earth where it had thought to sleep its deathless sleep and wait its hour of hours. . . .

His father. Who had created out of the absolute dust of the earth an evil sun by whose light men saw like some hideous adumbration of their own ends through cloth and flesh the bones in one another’s bodies.

Whatever the immediate objects of Bobby’s stumbling quest for understanding, they all lead back to this originary paternal infamy. Looking back over McCarthy’s career from this endpoint, we feel the urge to do as Bobby does in his obsessive readings in math: try “to trace his way back. Find a logical beginning.”

* * *

In McCarthy’s masterpiece, Suttree, the Ulysses of the American South, we observe a few years in the life of Cornelius Suttree, who seems about 35 years old, living in 1950s Knoxville, where the TVA is headquartered. A catfish trader estranged from his family after jilting his wife and child, Suttree has moved into a houseboat on the Tennessee River to carouse with drunks, ragpickers, and prostitutes. Like Bobby Western, Suttree has a problem with his dad, who speaks only once, in a letter in the book’s opening pages. “If it is life that you feel you are missing, I can tell you where to find it,” Suttree’s father pleads to his wayward son. “In the law courts, in business, in government. There is nothing occurring in the streets. Nothing but a dumbshow composed of the helpless and the impotent.”

This fragment is enough to conjure the cold legal mind of McCarthy Senior, and the next 450 pages of vividly slummed, unconscious-driven, magnificently sensory life are enough to prove him wrong. Suttree bumps into John Randolph Neal, Jr., an eccentric lawyer who in real life defended John Scopes in the scandalous Scopes “Monkey” Trial of 1925 and defended the promise of the TVA in the ’30s, and someone surely known to McCarthy Senior. In the novel, Neal knew Suttree’s father, he says, “quite honorably.” In Suttree’s tavern haunt, the tables are fashioned from gravestones salvaged from TVA floodland: “Whole families evicted from their graves downriver by the damming of the waters,” Suttree imagines one night, as he fingers their inscriptions:

Hegiras to high ground, carts piled with battered cookware, mattresses, small children. The father drives the cart, the dog runs after. Strapped to the tailboard the rotting boxes stained with earth that hold the bones of the elders. Their names and dates in chalk on the wormscored wood. A dry dust sifts from the seams in the boards as they jostle up the road.

The Tennessee River was dammed in the 1930s. Twenty years later, as told in Suttree, Knoxville endured a new phase of development: the razing of McAnally Flats, a neighborhood decrepit in infrastructure but rich in Black and queer community and an organic barter economy. Instead of power lines, this time it’s Interstate 40, which by 1956 would run from Tennessee and other Southern states all the way to California.

Even after he left the South, McCarthy couldn’t shake the inherited moral specter of dispossession. (His greatest interpreters, Joel and Ethan Coen, who directed No Country for Old Men, also made the greatest TVA film, O Brother Where Art Thou.) Even The Road, the cash-in McCarthy promoted on Oprah, and supposedly one of the great placeless novels, is infused with a subtle geographical specificity, which the scholar W. G. Morgan has meticulously mapped. From the first pages, amid the novel’s probably post-nuclear wasteland, a SEE ROCK CITY advertisement on the side of a barn sets us near the Tennessee–Georgia border. After passing this sign, father and son cross a “high concrete bridge over the river” (the Henley Street Bridge, under which Suttree lived in his houseboat) and gawk at the “long concrete sweeps of the interstate exchanges like the ruins of a vast funhouse” (a couple blocks from Suttree’s bridge, the knot of Interstates 40 and 275 that wiped out McAnally Flats). Then they stop at the remains of the father’s childhood home to study the pinpricks left in the mantle by the Christmas stockings of his youth. (The model for this house, McCarthy’s own childhood home in the suburbs of Knoxville, burned down three years after the book’s publication.)

“In the law courts, in business, in government. There is nothing occurring in the streets. Nothing but a dumbshow composed of the helpless and the impotent.”

The kicker is the dam. When the two spot a lake “in the scavenged bowl of the countryside,” the father explains that it is a dam that used water “to make lights. . . . It will probably be there for hundreds of years. Thousands, even.” Completed in 1936 on the Clinch River, not far from Knoxville, the Norris Dam was the TVA’s first big project. Six years later, thanks to the site’s isolation and cooling waters, and the abundant cheap energy from its turbines, the Army Corps of Engineers chose a small plot twenty miles to its north to build the secret laboratory, Oak Ridge, and enrich the ten pounds of uranium required to destroy Hiroshima.

In The Passenger, Oak Ridge is where Bobby’s mother, an area native displaced by the dam, found the most livable wage. (Placing third in the local beauty pageant, she had missed her shot at a scholarship.) The government kept her and thousands of her coworkers ignorant of the technology they were building. It was at the factory that she met Bobby’s father, a Princeton physicist passing through town to oversee the progress of the uranium. Now, in 1980, with both parents long gone, Bobby is a walking symbol of the TVA (and the McCarthy) land crisis. In a scene adapted largely from Suttree, Bobby is in East Tennessee visiting his “Granellen,” the definitional Southern grandma. She tells Bobby of the evictions she witnessed first for the Norris Reservoir in the ’30s and again, in the ’40s, for Oak Ridge: “They was some of em wound up just livin in the woods like animals.” She tells of the house she lost in the first round, with its mighty floor planks three feet wide, hand-planed from native walnut by Bobby’s great-great-grandfather in the 1870s.

From eviction to dam to war to bomb, late McCarthy leaves no reading to chance: “Western fully understood that he owed his existence to Adolf Hitler. That the forces of history which had ushered his troubled life into the tapestry were those of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, the sister events that sealed forever the fate of the West.” It’s almost too neat a summary, and it betrays a view of the world in which causation and heritage bind us to destinies we are powerless to comprehend, or divert. Caught in that painful discovery, Bobby finds himself in a New Orleans church, where he tries to exorcise his intrusive thoughts of Hiroshima:

He went there after the war with a team of scientists. My father. He said that everything was covered with rust. There were burnt-out shells of trolleycars standing in the streets. The glass melted out of the sashes and pooled on the bricks. Seated on the blackened springs the charred skeletons of the passengers with their clothes and hair gone and their bones hung with blackened strips of flesh. Their eyes boiled from their sockets.

It is not here, though, but with his Granellen, in the sleepy Tennessee holler where the father and son of The Road will one day stop to examine the vestigial monument of their doom, that Bobby’s inherited guilt crests into full view. Strolling down Granellen’s country lane, he looks around: “The rolling hills and ridges to the east. Somewhere beyond that the installation at Oak Ridge for enriching uranium that led his father here from Princeton in 1943 and where he’d met the beauty queen he would marry.” A driver stops him to have a word. “I know who you are, he said. As if he’d identified a Nazi war criminal hiking the roads round Wartburg Tennessee. Then he drove on.”

* * *

The southern town is a small place. Reputations grow large, yielding ritualized gossip on its front porches and Oedipal resentments in the souls of its young men. This is why the Southern gothic is so rich and so stereotypable a genre, and also why McCarthy wove into his books the paternal problem—down to his pen name, Cormac, for which he abandoned the hand-me-down “Charles” when he left the Air Force in 1957—that all of Knoxville knew led to his father’s eldest son. In his flight from patrimony, McCarthy asserted himself in a widening trail of territories: from the native East Tennessee gothic of his debut Orchard Keeper he escaped to the desert of the Border Trilogy, then fled even further, to the alleged nowhere of The Road and the remotest Spain of The Passenger. Yet the total itinerary bent to the pull of the Oak Ridge turbines, keeping the laboratory ever in view the farther he went. Speaking as another son of a Tennessee industry lawyer—a country music lawyer; it was TVA power that helped turn Nashville into a radio and recording mecca—I think the prime darkness at the heart of Cormac McCarthy’s fiction, always precariously perched over oblivion, began with his father, a fixer behind the laboratory that powered the possibility of human extinction.

Extinction never seemed nearer than in McCarthy’s final act, but neither Oppenheimer nor Bobby’s fictional father are the actual villains. While the engineers of Los Alamos spilled something into the world that can never be rebottled, what saddens McCarthy most is intellect itself. Alicia Western, Bobby’s younger sister, a mathematical genius and a schizophrenic, suffers accusatory, hyperrealistic hallucinations. A prisoner of her photographic memory, she is so alienated from society that she seeks refuge in an incestuous devotion to her brother, who has a keen mind for physics. (Like McCarthy, Bobby studied physics but never finished his degree.) The siblings’ love is mutual but anguished and unconsummated. It drives Alicia to suicide after a racing accident lands Bobby in a coma from which he wakes too late.

I think the prime darkness at the heart of Cormac McCarthy’s fiction, always precariously perched over oblivion, began with his father, a fixer behind the laboratory that powered the possibility of human extinction.

Stella Maris is a sort of prequel to The Passenger. It consists of six interviews between Alicia and the psychiatrist preparing her case study that explore Alicia’s life and family history, the ambitions of mathematics, and the devil’s bargain of intelligence. Though science skepticism is unwelcome in the age of Covid, for this daughter of Oak Ridge, “intelligence is a basic component of evil.” In her bratty, tortured, hard-earned way, Alicia is convincing. She has agreed to these interviews having already chosen suicide. (Worth the read alone is her calculation of the effects of drowning, a method of she has ruled out.) Pessimism like hers might have agreed with Alexander Grothendieck, the century’s most influential mathematician and, in the novel, one of Alicia’s correspondents. By 1972, the time of McCarthy’s novel, the actual Grothendieck had quit math to protest the military-academic complex, resigning from a lab Oppenheimer helped to found, to become a bearded hermit in the woods. In the novel, dejected and disillusioned with the field, he has stopped returning Alicia’s letters. “Grothendieck says somewhere,” Alicia narrates, “that twentieth century mathematics has begun to lose its moral compass.” Certainly Alicia’s own pessimism belongs to McCarthy himself. Characters aren’t their authors, but Alicia seems his spokeswoman in so much of Stella Maris. She has read ten thousand books, she says. At 22? A freak. But at 89? A writer.

Alicia recalls that when she started high school, at the ripe age of 12, she found the philosopher George Berkeley. “I sat in the floor and I read A New Theory of Vision,” Alicia says. “And it changed my life. I understood for the first time that the visual world was inside your head. All the world, in fact.” She ruminates on Berkeley’s contention in that book and elsewhere that only a sensory experience of an object can be said to be real, and therefore that the actual material existence of the object cannot be determined. “I sat there for a long time. Just letting it soak in,” she says. “It was hard to avoid the sense that the visual world is the creation of beings with the eyes to do so.” Unlike his empiricist predecessors John Locke or Thomas Hobbes (whom Bobby reads in The Passenger), Berkeley suspected that things aren’t real at all, and that we find “order and regularity” in the world only because an objective witness, an “infinite mind”—a God—stands watch over the universe when we blink or sleep or die.

Born in 1685 and raised during the political upheavals of the Glorious Revolution, Berkeley became fascinated, as McCarthy would, by the weaknesses of human perception and the psychological reasons for our dependence on God. Even as he transformed sensation into analytical argument, chiefly in his proto-novel Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonus (1713), Berkeley delighted in the tastes and smells that would fill that century’s later, thicker novels. McCarthy kept the sense-love but herded the prose in the reverse direction: from the ornate 18th-century Latinisms of Suttree and Blood Meridian back to the bare script of ideas. (McCarthy’s introduction to literature, he claimed, came at the University of Tennessee, where an English professor asked him to modernize the punctuation in a volume of Georgian prose.)

His first great novel before reaching the desert, Outer Dark, is a study in the limitations imposed by human sight.

Subjective idealism—Berkeley’s belief that reality is unknowable beyond our private perception—is one way to understand McCarthy’s escape from Tennessee to El Paso in the mid-1970s, and why he set his next six books, philosophical novels disguised as westerns, out there on the range. His first great novel before reaching the desert, Outer Dark, is a study in the limitations imposed by human sight. There, we grope our way through the “gathering dark” of some coastal swampland, “darker in some places than in others,” “from dark to dark” into “warm and breathing dark,” then into “right dark,” “nigh total dark,” “soaring darkness,” “full dark,” “depthless black,” “hopeless dark,” “constant dark,” and finally into “outer dark.” The title phrase describes the two-layer human depth of field at night: the foreground one can vaguely make out and then the pitch black beyond it. “Outer dark” is close to Milton’s hellish “darkness visible” but has more to do with what we can’t see: the unknowability of evil in a reality to which we are visually and morally blind.

Where the South is full of trees and bends and SEE ROCK CITY signs and post-TVA highways and pylons and wires, the desert is silent and flat. In a geometry with few obstructions, events leap into and out of reality as if hallucinated. Venturing as far into that terrain as possible, the first of McCarthy’s westerns, Blood Meridian, offers raw sense data of the kind that got Berkley thinking. That novel retells John Joel Glanton’s scalping expedition through Mexico in the late 1840s, a benumbing saga of settler genocide. In one scene, Glanton tests his pistol on an unsuspecting animal: “The explosion in that dead silence was enormous. The cat simply disappeared. There was no blood or cry, it just vanished.” Glanton’s crew loses a mule: “It went skittering off down the canyon wall . . . into a sink of cold blue space that absolved it forever of memory in the mind of any living thing that was.” Figures spring onto the horizon and into being at once: “They’d not been there, then they were there.” And when the hot horizon swallows them again, it does so in the language of Berkeley’s successor in Prussia, Immanuel Kant: “All lightly shimmering in the heat, these lifeforms, like wonders much reduced. Rough likenesses thrown up at hearsay after the things themselves had faded in men’s minds.” The “thing-in-itself” being Kant’s phrase for an essential unknowable reality. In the desert, we see not things but forms “roughly reproduced,” “shapes of mortal men,” and silhouetted “paper birds” instead of buzzards. The terrain gave McCarthy a stage for an allegory of human perception, of the simplicity, weakness, and gullibility of our understanding. Land is more than an asset repossessable by government, or even an inscription of history and memory. It becomes the sensorium itself. It is the kind of wild west wrought by Berkeley, who was also an influential proponent of colonial expansion and author of the pioneer motto “Westward the course of empire takes its way.” It was at Berkeley’s namesake campus of the University of California, believed at its founding to be the westernmost reach of Anglophone intellect, where Oppenheimer was teaching when the government asked him to start building their weapon.

But McCarthy’s Texas has none of the philosopher’s “order and regularity.” Instead, McCarthy writes, what you believe is what you get: “the order in creation which you see is that which you have put there, like a string in a maze, so that you shall not lose your way.” If there is no world beyond what we can sense, then perception itself seems an inseparable piece of that world. McCarthy expresses this most clearly in Blood Meridian, where he writes that perception is “no third thing” between self and matter “but rather the prime, for what could be said to occur unobserved?” In some transitive way, one’s small corner of the earth includes those billions of others who see, hear, and feel their own—and this network, rather than God, is where McCarthy leaves Berkeley behind. One big “common witness” is how McCarthy describes the roving band of scalpers: a “collective cognizance,” an “optical democracy,” a “communal soul,” an “egality of witness.” Judge Holden, Glanton’s second-in-command in Blood Meridian, puts it vividly: “every man is tabernacled in every other and he in exchange and so on in an endless complexity of being and witness to the uttermost edge of the world.”

Yet Judge Holden crafts this philosophy of oneness to justify the slaughter of every “savage” in his path. “War was always here,” he explains. “Before man was, war waited for him.” To question violence, he says, one might as well “ask men what they think of stone.” It also fuels his vendetta against the book’s protagonist, a teenager simply called “the kid,” whom Holden accuses of taking “witness against” him by harboring “some corner of clemency for the heathen.” (Similarly Suttree, in the quiet moral climax of his own novel, admits he has transgressed against the fact that “all souls are one soul.”) Judge Holden’s logic disturbs even more when set beside McCarthy’s own beliefs. “I think the notion that the species can be improved in some way, that everyone could live in harmony, is a really dangerous idea,” McCarthy said in a 1992 interview. “Those who are afflicted with this notion are the first ones to give up their souls, their freedom. Your desire that it be that way will enslave you and make your life vacuous.” Human perception both reveals and constitutes a world soaked in blood.

* * *

The genocides and expulsions of the American frontier would be reason enough, but the violence of McCarthy’s books stems largely from a more recent catastrophe, the threat of nuclear destruction. By 1982, when McCarthy was working on Blood Meridian and Bobby was fleeing his father’s legacy into rural Spain, the old doyens against the bomb—such as or Bertrand Russell, or Oppenheimer himself after Hiroshima—were gone. A new generation steeled by the Cuban Missile Crisis could now ask, at a scholarly remove, what the atomic age had done, and why. That year the New Yorker serialized the three essays of The Fate of the Earth, Jonathan Schell’s plainspoken consideration of the atomic threat soon republished as a bestselling book. In nontechnical language, Schell explains the probability that should a nuclear war happen now, in 1982, the death of our species might well come to pass. “‘Come to pass,’” Schell observes, catching himself, “is a perfect phrase to describe what extinction cannot do. It can ‘come,’ but not ‘to pass,’ for with its arrival the creature that divides time into past, present, and future—the creature before whose eyes it would ‘pass’—is annihilated.” With a language of vision and witness that feels like a model for Blood Meridian, Schell narrates the unthinkable waste of extinction, writing that “when extinction is reached, all the ‘spectators’ have themselves gone to the grave, and only the stones and stars, and whatever algae and mosses may have made it through, are present to witness the end.” Extinction means an end to the sensory universe that God watches for Berkeley, and that settlers watch for McCarthy. “In extinction, a darkness falls over the world not because the lights have gone out,” Schell explains, “but because the eyes that behold the light have been closed.”

The Passenger is a book about guilt. Not guilt for Hiroshima, but for participating in a meritocracy of mind that could have allowed a Hiroshima in the first place. Oppenheimer wrote in 1947 that “physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.” Too young for such primary blame, Bobby (born in 1945) and his fellow baby boomers must instead confront what Ian Buruma calls “the wages of guilt”: a society’s inheritance, at a generational remove, of a crime’s moral fallout. Today we tend to locate the United States’ original sin in chattel slavery or indigenous land theft, both of which McCarthy touches on in his work. But these late McCarthy books aim at a global wrongdoing, the point where the highest reaches of human intellect culminate in humanity’s self-destruction. It is for this legacy that McCarthy felt some vague but nagging charge of accessory, and against this legacy that Bobby, in the episodic closing pages of The Passenger, wins a final sense of quiet.

The Passenger is a book about guilt. Not guilt for Hiroshima, but for participating in a meritocracy of mind that could have allowed a Hiroshima in the first place.

McCarthy “wasn’t that good” at physics, he recalled in an interview. “I didn’t want to do anything unless I could be the best at it.” In that admission some might hear his high-achieving father. And in the premonitions of his great villain Judge Holden—“the man who sets himself the task of singling out the thread of order from the tapestry will by the decision alone have taken charge of the world”—some might hear the desert hubris of the soft-spoken, poetry-loving Oppenheimer. In the early 1700s, by contrast, Berkeley laughed at Robert Hooke’s new microscope, the quantum innovation of the day, claiming that it brought us no closer to discovering God’s reality. McCarthy’s books both seek the clarity and accept the blindness.

If Alicia’s curse is intelligence, her author seems to have fancied the same in his own gifts: a direct line to immediate sensory prose, a bottomless store of fresh figurative language, and the stamina required to chart an inquiry into human perception, in storybook form, across the better part of a century. “I will say one thing: you’ve opened my eyes,” an outraged small-town sheriff tells Suttree, the college-educated fuckup who has abandoned his wife. “I’ve got two daughters, oldest fourteen, and I’d see them both in hell fore I’d send them up to that university.” An old family home lost in the advancing flood of technological mastery, a village steamrolled by the highway of progress: McCarthy and his characters inherited a world where the sum of all intellect proves fatal to its parts.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.