The Complex Road for Indonesian Women in Politics

Interviews with female politicians, who speak about the challenges of gender expectations. Activists brings a sculpture depicting an oligarchy-themed octopus during a rally celebrating International Women's Day in Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo: Tatan Syuflana / AP.

Activists brings a sculpture depicting an oligarchy-themed octopus during a rally celebrating International Women's Day in Jakarta, Indonesia. Photo: Tatan Syuflana / AP.

Indonesia has engaged in affirmative action to encourage better representation of women in politics since 2008. The General Elections Law requires political parties to ensure that at least 30 percent of candidates for seats in each electoral district are women, and it stipulates what is known as a “zipper” system, whereby one in every three candidates nominated by a party must be a woman.

However, the majority of Regional Legislative Councils (DPRD) at both the regency/city and provincial levels have less than 20 percent female membership. The House of Representatives, meanwhile, only achieved 20 percent women’s representation in 2019.

Even with affirmative action in place, numerous women candidates encounter great obstacles to securing a seat in the House or DRPD. Their struggles start at home, where they bear the burden of rigid gender expectations. Beyond that await cultural, structural and institutional barriers from within and outside the party.

Some former and potential legislative candidates spoke to Project Multatuli about the steep road they had embarked on to ensure women’s voices were heard in public life.

Okiviana, Central Java

Local media used srikandi, the Indonesian word for heroine, to describe Okiviana, 36, when she became one of only nine female councilors on the 45-member local council in her hometown of Sukoharjo, Central Java, in 2019.

Okiviana was a newcomer to politics. Just a year before, she had earned her master’s degree in social development and welfare from a well-respected university in Yogyakarta and had taken a position as a social worker for Program Keluarga Harapan, a government social assistance service for underprivileged families.

That was when National Awakening Party (PKB) members began hearing about Okiviana. They eventually asked her to run for the Sukoharjo DPRD on the party’s ticket.

She recalled that the PKB was having difficulty recruiting women candidates to replace a woman incumbent who had retracted her candidacy over family matters. If the party failed to meet the 30 percent quota for women candidates, it would be barred from the election.

Okiviana said yes to the party’s request to run and quit her day job, leaving her with no income. The demands of the campaign trail meant she had no days off, and she would often meet with her constituents until 1 a.m.

Despite her hard work and track record, Okiviana chooses to attribute her success to the financial support and network of her father, a retired civil servant.

“Running for office doesn’t necessarily mean I’m the strong one. There are people behind me. In this case, it’s my father,” Okiviana said.

To run the campaign, they had to spend a large sum of money. These resources were among the reasons the party placed Okiviana at number one on the ballot, a strategic position that many candidates vied for.

A 2014 study by the University of Indonesia’s Institute for Economic and Social Research (LPEM) found that campaign costs in that year’s elections ranged from Rp 500 million (US$33,650) to Rp 4 billion.

“I think it’s quite extraordinary for a woman to be independent in politics. Because as far as I know, for most to stand on their own feet, it would be really difficult. Be it from the financial and political pressures [or otherwise], there are many factors,” she added.

Boundaries between the personal and the professional are often blurry, or even deliberately ignored.

The country’s money-driven political system means candidates’ financial resources are a key determiner of whether they will secure a seat in a legislative body. During her campaign, Okiviana met a number of constituents who asked for material goods in exchange for their votes. Okiviana sees vote-buying as a further burden for women candidates who lack resources.

A study of the 2019 election results by the Center for Political Studies at the University of Indonesia (Puskapol UI) found that of the 118 women candidates elected to the House of Representatives, 53 percent were active party members, such as administrators, DPRD members and former regional heads. Some 41 percent had a kinship with elites. Meanwhile, 6 percent were professionals.

“Money politics can really harm women. Not only in terms of representation but because eventually, it’s those who are strong [financially] who will get the seats, regardless of whether they can amplify women’s aspirations or not,” she said.

Even then, abundant resources do not guarantee women a smooth political career. Boundaries between the personal and the professional are often blurry, or even deliberately ignored.

At home, Okiviana has the full support of her husband, whom she married in 2017. She shares domestic chores with him, and he sells shoes online.

On the campaign trail, Okiviana’s political opponents spread a rumor that she was a janda (widow or divorcée), a status that is stigmatized in most Indonesian communities.

“People won’t talk about duda [widow or divorcé] that way. Instead, they encourage them to get a wife,” said Okiviana.

Okiviana said she believed those kinds of personal attacks reduced women’s confidence in running for office, even if they had the capacity and credentials.

“Politics is still considered a men’s thing,” Okiviana added.

This leads to a limited gender perspective in the legislative body, which Okiviana has been trying to redress throughout her term, particularly as a member of Commission I overseeing law and governance.

She has worked with women and children’s organizations and disseminated information on the recently passed Sexual Violence Eradication Law in hopes of improving the treatment of victims of abuse.

To improve her capacity as a lawmaker, Okiviana actively sought out and participated in training sessions, often held by non-political organizations amid a lack of offerings from the party.

She has also shared her experience as a politician in guest lectures at various universities. Her experiences convinced her that a lot more women and young people needed to enter regional legislatures, which were dominated by old, rigid ideas amid the absence of term limits for lawmakers.

Despite this lack of women’s representation, Okiviana has decided not to seek reelection in 2024 after weighing her professional and domestic aspirations.

Okiviana and her husband are trying to have children after five years of marriage. Staying in politics, which has drained her time and energy, would make it difficult for her to manage her polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which she has been suffering from for a long time, she said.

“If a woman can only choose one [between the personal and the professional], that’s not a problem, and it’s not something that should be exaggerated. But if she decides to choose both, that’s very commendable. So don’t be limited by the stigma of other people, society, because the people who truly know are ourselves,” she said.

Anggiasari Puji Aryatie, Yogyakarta

“I know I’m not a celebrity, nor am I rich. I think it’d take a big miracle for God to bring me maybe 50,000 to 60,000 votes,” said Anggiasari, 43, reflecting on her unsuccessful electoral bid four years prior.

Anggi, as she is often known, ran for a House seat in the Yogyakarta electoral district on the NasDem Party’s ticket. Anggi has achondroplasia, or dwarfism, and has long advocated for disability rights.

In the 2019 election, she managed to collect 6,618 votes, while the eight candidates elected in Yogyakarta won between 65,000 and 170,000 votes each.

Anggi said that while her party had provided assistance with transportation and some campaign supplies, the campaign trail could be very difficult for women candidates without financial freedom. Costly billboard installation fees and taxes were some of the many expenses. Anggi’s efforts to create a campaign that was inclusive of candidates and voters with disabilities, including by providing sign language interpreters and transportation, added to the costs as well.

“If parties nominate more candidates with disabilities, I hope they will be able to help our friends with disabilities,” said Anggi.

Instead of financial capital, Anggi relied on social capital. She received voluntary assistance from college friends and the disabled community, a vast network she had built in part by working at nonprofits. In order to help voters with disabilities get to polling stations (TPS), she partnered with Difa Bike, a motorcycle taxi company catering to people with disabilities in Yogyakarta.

Before entering politics, Anggi spent years struggling to land a job, despite holding a bachelor’s and a master’s degree.

Her experience illustrates the difficulties and discrimination that women and people with disabilities experience in their efforts to be financially independent.

Some 23 million Indonesians were living with disabilities in 2019, according to a government study. Only 36.9 percent of women with disabilities participated in the labor force, the study found, while 58.9 percent of men with disabilities did so, both far below the national workforce participation rate. The study also noted that many people with disabilities worked informal jobs for low wages.

Meanwhile, the general women’s labor force participation rate in Indonesia has steadily grown, reaching 54.42 percent in early 2023. However, the figure is still far below that of men at 83.98 percent, according to Statistics Indonesia (BPS). The data also shows that women tend to work in the informal sector.

Women’s average income is 23 percent less than men, even when they are university graduates, and they occupy only a quarter of high-paying managerial and supervisory positions. Even in these positions, they are paid less than men.

After the 2019 election, Anggi once again struggled to find a job, especially in the nonprofit sector in which she had had experience, as she was assumed to have political affiliations even though she was not a party official.

Despite the daunting professional and personal stakes, Anggi has chosen to persist in politics. She will be running again next year for a seat in the Central Java DPRD. Her goal remains the same: to ensure that the government’s budget is inclusive of people with disabilities.

“Because without a budget, the law on people with disabilities remains merely a text without any concrete evidence of its implementation. That’s the main reason I decided to join the race,” she said.

Sri Handayani, East Java

Sri Handayani’s first political opponent is her inferiority complex. The 31-year-old said her economic and educational backgrounds were far below those of other candidates.

“I feel inferior seeing other candidates. Many of them are businesspeople,” said Sri.

Sri is a member of Jamkeswatch, a wing of the Confederation of Indonesian Trade Unions (KSPI) overseeing the implementation of the National Health Insurance (JKN) program. She advocates for free and affordable access to health services and facilities for low-income patients.

Her advocacy began in 2014, after her son fell ill and she could not afford to bring him to a doctor. Thankfully, she received help in activating her family’s government health insurance plan.

At the age of 15, Sri was forced to quit school after graduating from junior high school in Magetan, East Java, and she soon started working as a shopkeeper in Surabaya. Sri married her husband at the age of 17, and since then has worked various jobs, including as a babysitter, parking attendant and catering staff member.

“I used to cater at events and often had to come home late. In the end, my husband said I had better stop working, as people would have negative assumptions seeing me come home late at night. I just stay home, and if there’s [work], then I’ll do it,” said Sri.

Thanks to her tireless advocacy for social security accessibility, Sri received funding to study for the senior high school equivalent (Paket C) national examination. The help came from the head of the Sidoarjo subdistrict, where she lives. She earned her senior high school degree in 2021 and signed up for university, but she was only able to attend the first few classes before she failed to pay the tuition fee.

“My hope is that when I have a higher educational level, I will get a better job,” said Sri.

While a better job has yet to come her way, Sri has used her senior high school graduation certificate to sign up as a candidate for the Labor Party (Partai Buruh) for the Sidoarjo DPRD. She hopes to advocate for even more people on the council. Support from her fellow party members helps her battle her inferiority complex.

“We rely on what each of us has, since many of us are workers. There can be donations, like Rp 5,000, Rp 10,000,” Sri said.

“Spending big money doesn’t guarantee a win,” she added.

Political parties tended to treat the women candidate quota merely as a hurdle to overcome.

Even with the low rates of women’s participation in politics, some political parties are pursuing a rule change that would effectively reduce the 30 percent minimum for women candidates.

General Elections Commission (KPU) Regulation No. 10/2023 on candidacy for the House and DPRD, issued recently after consultations with House Commission II and the government, will result in further constraints on women’s candidacies through a change in rounding practices.

If the raw required number of women candidates in an electoral district, obtained by finding 30 percent of the candidates in that district, contains a decimal, the number of women candidates is rounded down if the decimal portion is below five tenths and up if it is five tenths or above. The previous rule required rounding up in all instances.

Based on the calculations of the Coalition of People for Women’s Representation, under the new rule, electoral districts with four, seven, eight and 11 candidates will see a lower minimum number of women candidates than under the previous rule (see table below), bringing the actual representation to below 30 percent.

The regulation will affect the minimum number of women candidates in 38 House electoral districts. This does not include DPRD electoral districts, meaning the change could affect the candidacy of thousands of women, according to Titi Anggraini of the Association for Elections and Democracy (Perludem), which is part of the coalition.

Titi said it was difficult to expect the KPU to form consistent or progressive election regulations because it lacked a strong democratic ideological foundation.

“I think the biggest problem is [the KPU’s] poor independence. The commission is held hostage to what parties in the legislature want,” said Titi.

Perludem executive director Khoirunnisa Nur Agustyati lamented that political parties tended to treat the women candidate quota merely as a hurdle to overcome and only started looking for women to fill the spots close to the candidate registration period. Instead of evaluating their performance in recruiting women, parties pushed for regulations that were detrimental to them, she said.

“If parties are asking for capable women, the question is what have these parties done [to help improve] the women?” Khoirunnisa said.

The Coalition of People for Women’s Representation has filed a request for judicial review of the new KPU rules with the Supreme Court after the KPU failed to revise the regulation as promised in May 2023.

Meanwhile, KPU commissioner Idham Holik said the institution would respect the judicial review request. He showed Project Multatuli a document containing a concluding statement from a hearing with House Commission II that asks that the KPU remain consistent in implementing the existing PKPU.

Okiviana believes the regulation undermines women’s interests and stifles their voices. The lack of diversity of perspective in the legislature makes women’s advocacy work even more difficult, such as in the case of the Sexual Violence Eradication Law.

“At my commission meeting, I proposed a lactation room at the DPRD office, and some people asked what for. So it was not considered important. Even advocating for a mere lactation room is already hard as it is,” she said.

Even though Indonesian elections use the open-list proportional representation format, the upper and strategic numbers are still a matter of contention between candidates.

Khoirunnisa encouraged political parties to provide training and assistance for women members and candidates because the starting lines for women and men were so different.

The government funds allocated to political parties with seats in the House and DPRD based on the number of votes they won could be used to hold regular political education courses for women, she said. Women could learn, for instance, how to strategically utilize limited funds to collect votes.

“Women candidates’ campaigns [can be] sporadic. There [may be] no target for the number of votes that must be collected and at which points. They don’t get such information from the party, so they are not as electable,” said Khoirunnisa.

She added that parties typically only spent time and effort on women who were already well positioned to run for office. Women candidates without social or economic privilege had to navigate the struggle of public life on their own, even if they encountered legal problems. And that unpleasantness could make them reluctant to run for office again in the future.

“There is an assumption that women do not have the capacity. So far, when we talk about capacity, the question is whether women have been given as much access as men. If opportunities finally open up for women, which women will have first access to those opportunities?” she added.

Esti, East Java

Esti, 49, who asked to be referred to with a pseudonym for this article, had to navigate her candidacy alone. She ran for the Sidoarjo DPRD in 2019 as a candidate for a party she asked not to be mentioned.

Esti said she was ostracized because she had been nominated as a candidate without having served on the party’s board. Shortly before the candidate registration period opened, a female lawmaker who was on the party’s Central Executive Board (DPP) proposed Esti as a candidate because of her years of experience in health and social security.

“There was envy. I got a strategic number, which is also the number of the party on the ballot. Those who occupy that number are [usually] board members. The first woman must be a board member, at least at the branch level,” said Esti.

“Eventually, there was a protest. The numbers were overhauled. But in the end, I got the same number because I got a recommendation from someone important.”

Even though Indonesian elections use the open-list proportional representation format, the upper and strategic numbers are still a matter of contention between candidates.

Under the voting system, constituents cast their vote for a particular candidate, not the party as a whole. However, low numbers or the same number as the one assigned to the party on the ballot are still considered strategic simply because voters can easily remember them.

A Working Paper on Strengthening Women’s Political Representation in Indonesia compiled by United Nations Women and Cakra Wikara Indonesia found that in the 2019 election, the majority of political parties placed women at number 3.

In that year’s election, of the 1,280 candidates who were placed at number 1, only 18 percent were women. An analysis of data from the last three legislative elections shows that women who were listed as number 1 on the ballot had a chance of winning of above 40 percent.

Esti’s struggles did not stop with her number on the ballot. The absence of support from the party and the Branch Leadership Council (DPC), which backed the incumbent, required Esti to create a campaign team outside the party. She spent at least Rp 1.5 billion on the campaign, which she collected from the sale of her house, income from her business and support from her husband and network.

For Esti, securing her husband’s permission to run for office was a must. She eventually earned his permission, which she said was a luxury she knew was not shared by many other married women. She added that she had to ensure that her family matters were handled well before she worked on projects outside the home.

“Because it’s like gambling. Women are afraid that once they spend so much money, what if they don’t end up winning? Especially if they are not financially strong,” she said.

On the campaign trail, Esti provided free door-to-door health services. To ensure that her votes were safe, she spent Rp 15 million at the party’s request to employ party witnesses at the polling stations, in addition to assigning her own poll witnesses.

However, when she saw the election results, Esti suspected that many of her votes had not been counted, and she noticed that the incumbent had seen his votes skyrocket. She reported the case to the DPC, but it was dismissed because of a lack of evidence. Without party support, she could not file a complaint with the Election Supervisory Body (Bawaslu). She eventually lost in the 2019 elections.

“Very closed, exclusive and a game between the elites,” said Esti.

Although it is forbidden, votes are still bought and sold within parties, said Indonesian Women’s Coalition secretary general Mike Verawati Tangka. She added that the terms of these illicit exchanges might be set in an initial agreement in which women lacked bargaining power. This meant that they were still seen merely as vote-getters.

“Some of the women got enough votes and were quite competitive with other candidates. The problem is that it eventually depends on how the party decides,” she said.

Islamic organizations played an important role in supporting women candidates in the country.

After the 2019 elections, Esti was placed on the party’s board in Sidoarjo, which she said was because of the number of votes she had won.

It was not easy for women to become party board members, Esti said, despite a regulation stipulating that women must hold at least 30 percent of party management positions.

The strategic position has given Esti hope that she can finally secure a seat in the Sidoarjo DPRD in next year’s election. In her electoral district, her party has five female and three male legislative candidates, but two of the women candidates only serve to fill the quota and will not seriously compete. This is still common practice among parties.

For this reason, Esti expressed her hope that parties would recruit women members as early as possible instead of simply rushing to meet the quota just before an election. The country’s male-dominated parties, she said, did not consider it important to provide political education for women.

“[This is] because, firstly, it is very difficult for women to get permission from their husbands. In Sidoarjo, some religious beliefs are very strong. So they may feel that it is inappropriate for women to sit on the legislature,” Esti said.

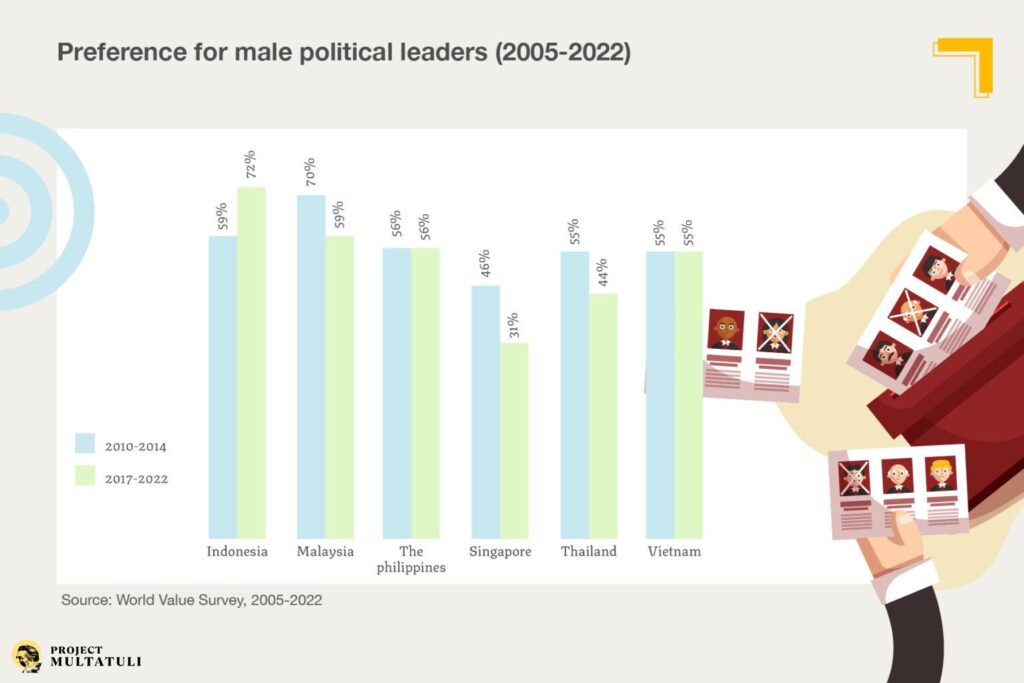

The 2005-2022 World Value Survey, cited in a Westminster Foundation for Democracy report, found that more than 50 percent of Indonesian respondents preferred men as political leaders over women. This preference increased by 14 percent in the country from 2006 to 2018, a much greater increase than in neighboring countries such as Malaysia.

The report emphasized the link between such preferences and the religiosity of society, although it acknowledged that Islamic organizations played an important role in supporting women candidates in the country.

“Patriarchy is still very much here because our politics and political parties are still very masculine. More often than not, decision-making processes do not involve women,” said Khoirunnisa of Perludem.

Siti Wadiatul Hasanah, West Nusa Tenggara (NTB)

Siti Wadiatul Hasanah has bitter memories of her 2014 candidacy for the regional legislature as part of the Crescent Star Party (PBB).

Hey candidacy was advanced simply to meet the 30 percent women candidate quota. She was promised funding support only to receive a small stipend to cover administrative costs. Her experience on the ground led her to believe that politics was indeed a dirty business.

“It’s like they’re allowed to do just about anything,” she said.

After she failed to secure a seat, Wadiah shifted her attention to Women’s Solidarity (SP) Mataram, a nongovernmental organization that focuses on empowering and advocating for migrant workers who face problems.

Wadiah has an avid interest in labor rights, having been a migrant worker herself in Jordan from 2010 to 2012. She was not aware that she had been recruited under an illegal scheme until her departure from Jakarta was postponed six times.

She found out later that this was common practice, especially in West Nusa Tenggara (NTB), which sends the third highest number of migrant workers abroad by province. Her experience allows her to empathize with the obstacles that women migrant workers face abroad.

In 2021, Wadiah and her husband founded their own organization, the Al-Kautsar Migrant Foundation, to focus on assisting troubled migrant workers, specifically in information dissemination to prevent illegal deployment and help mediate the return of workers on illegal contracts.

In the hope of advancing pro-labor policies, Wadiah joined the Labor Party and will be vying for a seat in the West Lombok DPRD in the upcoming election.

“The Labor Party is a new party that shares my vision. It happens that my husband is an active member of the party’s provincial branch and offered to have me run for office at the district level,” said Wadiah.

Learning from her experience nine years ago, Wadiah says she will not let herself be treated as a party accessory.

“It’s true that I don’t have any financial investments, but I do have social investments,” she said, referring to her years of labor rights advocacy that she believes will help her secure votes.

Wadiah said her biggest challenge on the ground was the lack of political knowledge among the district’s constituents. Relationships between politicians and constituents were commonly transactional.

“Voters think, ‘If money’s involved, we’ll accept it. If there’s no money, then we won’t vote,’” she said.

Even so, Wadiah believes some people are finally starting to accept women as politicians who can represent them and amplify their voices.

Nurwahidah, West Nusa Tenggara (NTB)

Nurwahidah, 39, chose to learn from failure.

She left her hometown of Bima on Sumbawa Island to teach at a private school in Mataram on Lombok. She has tried twice to secure a seat in the House. She failed on her first try in 2014, which she believes was the result of a lack of party support.

Five years later, Nurwahidah joined forces with the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) to run for a seat in the House in the Lombok electoral district.

“At that time, the party’s regional leaders said Lombok would result in more votes, even though I’m from Bima,” she said.

She managed to gather support from parents and teachers at her school, but it was not enough to win the election.

She attributed the failure, among other things, to the insufficient number of witnesses deployed at polling stations to monitor the party’s votes.

But Nurwahidah has refused to give up. She will be running again next year, this time for the West Nusa Tenggara DPRD. She is preparing herself, especially mentally.

“Candidates must be strong mentally, because not everyone can accept them,” she said.

Nurwahidah also relies on her social investments to build a good rapport with her constituents. While she believes her status as a single woman could present a challenge for her candidacy, Nurwahidah is seeking to prove people wrong.

She focuses on women and children’s empowerment and legal protection and has been active in the Lombok Empowered Women Foundation. She once assisted an elementary school student who was a victim of abuse. Apart from her family, Nurwahidah also receives support from female lawmakers in the PKS.

In 2022, women made up only 1.59 percent of the West Nusa Tenggara legislative council, according to Statistics Indonesia (BPS) data. The regency and city-level legislative councils fared better, but none of them managed to reach the 30 percent figure for women’s representation. For instance, women represent 25 percent of councilors in Mataram and 16 percent in Bima.

Nurwahidah believes women can conquer the stigma that often attends their participation in politics. She has seen how a number of women figures in the province have managed to turn around negative public opinion of women’s capabilities.

“There will always be stigma, but we must let people see what we’ve got,” she added.

Translated into English by Ardila Syakriah. The piece was first published in Indonesian.

This article first appeared on and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.