The Betrayal at the Heart of Time Magazine

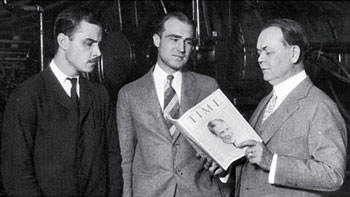

Why did Henry Luce, titan of 20th-century journalism, bury the legacy of his boyhood friend and rival, Time magazine co-founder Briton Hadden? That's the provocative and never-before-told story at the heart of the new book "The Man Time Forgot." Truthdig interviews its author, Isaiah Wilner. (Above: Hadden, left, and Luce, center, in 1925.)

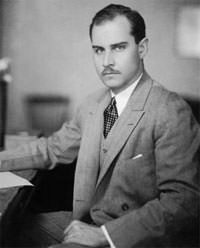

Time Inc. co-founder Henry Luce dominated journalism in a way that only William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer did before him, and perhaps only Rupert Murdoch has done since. Yet the world-striding, king-making activities of Henry Luce (1898-1967) weren’t what interested first-time author Isaiah Wilner. Instead, Wilner focused on the prefix of Luce’s title: “co-founder,” and wondered: Whatever happened to the person who should be sharing in the credit?

That question was the starting point for Wilner’s new book “The Man Time Forgot: A Tale of Genius, Betrayal, and the Creation of Time Magazine.” The book relates the never-before-told story of Time co-founder Briton Hadden, Luce’s boyhood friend and rival — the true creative genius behind the magazine, whose untimely death in 1929 at age 31 allowed Luce to bury Hadden’s legacy and to claim full credit for creating Time.

Wilner’s book follows his two protagonists through their earliest childhoods, prep school rivalries, their entrance to Skull and Bones at Yale, their hand-to-mouth first years at the helm of Time, and Luce’s ultimate betrayal of Hadden. These accounts lend nuanced dimension to one of the most lionized public figures of modern history.

The book derives its narrative thrust from the complex relationship between two young men who were, on their face, near polar opposites — Hadden, gregarious, outgoing, a born editor; Luce, introverted, contemplative, a slower study. These traits, however contrasting, ended up complementing one another, and provided the spark that would birth the nation’s first newsweekly magazine — and with it, the start of a national news media.

Wilner, 28, a former newspaper reporter and TV writer and researcher, followed in the footsteps of Hadden and Luce at the Yale Daily News, where he first stumbled on the germ of the idea that would become “The Man Time Forgot.” Since coming out earlier this month, the book has garnered positive reviews in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, and Vanity Fair ran an exclusive extended excerpt.

Wilner spoke with Truthdig managing editor Blair Golson about his book’s controversial thesis; about spending five years crawling around in other people’s heads, and about how the nation seems to be inexorably pulling away from the idea of sharing a national story.

Disclosure: Wilner and I (Truthdig managing editor Blair Golson) are longtime friends. We were roommates for part of the time Wilner was writing his book; I read early chapters; and I even contributed to some of the research and fact-checking. I offer this dialogue between us in the sprit of Interview magazine, in which most of the interviewers and interviewees have relationships similar to those of mine and Wilner’s. (And I asked only one question to which I already knew the answer: the first one.)

Truthdig: What sparked your interest about this story? Wilner:

When I was back at the Yale Daily News, I would sit in the board room proofing the front page each night before it went to press, and right up above my head was this dusty portrait of Briton Hadden.

I was intrigued by the smile on his face. It was almost a Mona Lisa smile — mysterious — almost like he was holding a secret. There was a lot of talk in the Daily News that Hadden was the co-founder of Time magazine, but nobody knew anything about him.

There’s a plaque outside the building — which is named after him — that reads: “His genius created a new form of journalism.” If this was the case, it seemed odd that nobody would know about him.

So my question from the outset was: Who is Briton Hadden, and how come nobody’s ever heard of him?

Truthdig: When did your research start to pick up steam?

Wilner:

When I got access to the archives at Time Inc., that’s when the project really took shape. There were Hadden’s letters, Luce’s letters, a wealth of oral history reminiscences, and even old corporate records. And all the sources really pointed to the friendship and rivalry of Hadden and Luce as being the true drama behind the rise of Time Inc. And this was a story that had never been told.

Truthdig: But what did Time accomplish that makes the story of its founding worth reading about in the first place?

Wilner: Hadden and Luce had started Time with the idea that people were too busy to read all the news that was coming out in papers, radio, film, and that people needed somebody to boil it down and make sense of it. But what they ultimately found out, when Time moved to Cleveland from New York in 1925, is that while people were indeed inundated with all kinds of media, they still didn’t have one good source to get a basic world report. So that’s what Time provided the nation, and it was the first publication to do so.

Also, if you go back and look at the old newspapers from that period of time, they were not very well written. The New York Times would print long transcripts of trials or debates, and people were just not able to wade through all this stuff.

So Time pioneered a style of writing called TimeStyle, which was brash, curt, punchy, athletic, and had a great sense of humor; it transformed the news into a form of entertainment. This whole way of covering the world in an accessible way and personifying the news spread to TV, radio, to the great large-circulation daily newspapers; it helped create what we now think of as the national media.

Truthdig: Every story needs a villain. Does Luce, because of his betrayal of Hadden’s legacy, play that role in your book?

Wilner: I don’t think so. I tried to write the book from the perspective of “Why did Hadden become such good friends with Luce, and why did Luce become such good friends with Hadden?” So I think we see Luce as brilliant, driven, a scholarship boy who was desperate to get ahead — and an outsider always wishing to be in the inner circle. Hadden, on the other side, was wealthy, popular and extremely social; he had the gift of gab. Things came easy to him, whereas Luce has to scrap so hard — despite how brilliant he was — to make a mark. Hadden was a natural; he did what came most quickly to him. He was naturally a journalist and had been ever since the earliest days of his childhood. Luce was more trying to get ahead; he wanted to be powerful and influential.

I don’t think Luce was evil. But at the same time, we have to consider: What was the moral character of this man? Well, this was somebody who spent 38 years betraying the best friend he ever had.

Next Page: It’s clear from reading his letters that Luce never really got over that loss: those letters display the rawest emotions he ever wrote.Truthdig: Why do you think Luce went out of his way to make sure Hadden didn’t enjoy his full share of credit? Vanity? Insecurity? Harboring a grudge?

Wilner: Luce had finished so close behind Hadden for so long — they were rivals ever since Hotchkiss [prep school], where they had competed to be the editor of the newspaper, and Luce had finished behind Hadden. Then what really hurt Luce was losing the chairmanship of the Yale Daily News to Hadden by just one vote. It’s clear from reading his letters that Luce never really got over that loss: Those letters display the rawest emotions he ever wrote.

But the thing was, Hadden really picked Luce up after that and offered him the chance to write half the editorials, and told him they were a team — 50/50. Hadden really inspired Luce and helped him to become a stronger person than he was. So Luce’s love for Hadden and his admiration for Hadden were always bound up with a sense of envy and a strong desire to beat Hadden in the end.

And that was amplified during the founding years of Time. Hadden insisted on remaining the editor for the vast majority of the time, and Luce badly wished to edit, but he was forced to basically balance the budget. Luce was balancing the budget for four and a half of the first six years, and didn’t get an extended crack at editing until 1928. So there was a lot of bound-up hostility, and in fact, they weren’t speaking during the last year before Hadden’s death.

So Luce loved Hadden, but he was also jealous of him; and he wondered whether Hadden respected him as much as he respected Hadden. And in fact, during his life, Luce would often ask Hadden’s friends what Brit was saying about him. And Hadden would say, “It’s like a race. No matter how hard I run, Luce is always there.”

So as the book progresses, you see Luce climbing higher, becoming stronger, becoming a better writer; you see him learning from Hadden, becoming more polished socially, marrying a beautiful socialite, so he’s just inching closer and closer and closer to Hadden, until the moment of Hadden’s death, when Luce is just about to surpass Hadden, and Hadden, by dying, robs Luce of the chance to beat him.

So his erasure of Hadden’s legacy was born out of a deep-seated sense of rivalry and a weak ego.

Truthdig: What about in after years? Why didn’t he ever set the record straight?

Wilner: Once the lie got started going, it was very difficult for Luce to manage it. Once he began to stand on stage and take credit for that achievement, he couldn’t very easily stop that train, and say, “Wait a minute, everybody. Actually, Time was my friend Brit’s idea.” And the reason he couldn’t do that is because he was traveling the world as a media missionary, giving stump speeches, especially on America’s role in the world, and he became an extremely controversial public figure. And what propped all this up, what maintained his status, was the fact that he was known as the creative genius who had envisioned and brought about the Time Inc. empire.

Once he arrived as a great man, Luce had a difficult time admitting to himself that he wouldn’t have been who he was without the influence of Briton Hadden. His whole personality and direction had been swayed by someone who, for a time, anyway, was a greater man than he. That’s a very difficult thing for a great man to admit to himself, and something he might want to bury.

Truthdig: As this angle developed, and the truth began to become clear about Luce’s squelching of Hadden’s contributions, were you afraid that if Luce’s heirs or Time magazine found out they’d cut off your access to the family papers or the Time Inc. archives?

Wilner: The archivists at Time were actually really glad that somebody was finally telling Hadden’s story. And the Luce family was extremely helpful. I thought my job was always to be fair, and that if I could tell the story of this amazing friendship, it would do justice to both men.

Look, people aren’t perfect. And it’s unfortunate that Luce couldn’t bring himself to do the right thing, but at the same time, that shouldn’t outweigh what they accomplished together.

Truthdig: Knowing, as you must have, how much that success of the book was going to depend on your ability to bring this betrayal to life, did you have to resist the temptation to interpret the facts in a way that would make Luce’s actions seem even more dramatic?Wilner:

No, because I basically just read every public statement that Luce ever made and anything I could find that he said on the TV or the radio. So the question was: How did Luce treat Hadden’s legacy?

In other words, when I came in, I didn’t know Luce had buried Hadden’s role in history. But what happened was, when I went back and read Time magazine, I noticed that Luce had taken Hadden’s name off the masthead within two weeks of his death. This shocked me, because it had never been reported before. And then as I explored the topic further, I learned a lot of other things that made plain just how deep this betrayal had gone.

Truthdig: It’s a truism that the history books are written by the winners. Did your exploration of this topic lend you a deeper understanding of that?

Wilner: History and what people think is history are two entirely different things. What I learned after working on this book is that history is a dialogue between the present and the past. And our view of the past changes with the decades, but it also gets more accurate. The hope is that history becomes more accurate with each year. Perhaps we lose some documents over time, but the hope is that more documents will become available to give us a fuller picture of the past.

I think that’s the case here. The prevailing view was that Time was Luce’s idea, and nobody even thought about Hadden. Nobody had any specific information about what he contributed to the partnership. I hope that my book simply corrects the record.

Truthdig: You spent almost five years working on this book. That’s almost as long as Hadden spent working on Time. Did it feel at times that you had lost your bearings under the weight of so much material and so much time spent as basically a solo operation?

Wilner: One of the reasons it took so long is because I read every document that related to Hadden’s life. There’s no stone left unturned. And I had to process all that information before I could get it into a narrative. So when the writing process began, I had to teach myself how to write a book, and I discovered it over a couple of years. I ended up boiling down an 850-page manuscript to about 350 pages.

Next Page: The middle class of the 1920s was so upwardly mobile.Today, the middle class seems downwardly mobile. For example, we frown on intellectualism. Presidential candidates would never want to appear intellectual. Whereas at that time, people wanted to be intellectual. Truthdig: Given that you were an editor of the Yale Daily News, you were obviously already intimately interested in this topic. Did you fear that this wouldn’t appeal to more than a very narrow band of readers who are already familiar with the Ivy League, Skull and Bones, and institutions like those?

Wilner: I always thought it would appeal so much to everybody because it appealed so much to me. I guess I was a little nave, kind of the way Hadden was nave. He didn’t come up with Time because this was something that would appeal to millions of people. He came up with Time because it was the type of magazine he wanted to read. He saw the news in terms of personalities, and he wrote it in terms of personalities. I felt it was an interesting story. And especially when I started reading the oral-history reminiscences of Hadden, and I started reading about how self-destructive he was and how attractive he was to the people around him, and how much he influenced all his friends since the early days of prep school. He struck me as a cinematic personality — somebody who was larger than life.

So that grabbed me, and then about a year into the project, I interviewed Hank Luce, and he gave me access to the Luce papers, and I was just blown away by how brilliant Luce was, and how hard-working, what an astonishing childhood he had in China, with being sent away to this cruel boarding school at the age of 10, how he had willed himself to cure his stutter, and how he was always moving onward and upward. His will to power was remarkable. So the contrast between the natural and the arriviste was fascinating to me. I also think Hadden and Luce, even though they were the elite of the elite, that didn’t stop them from coming up with an idea that they felt would strengthen American democracy. So they came from an elite background, and perhaps it was an elitist notion that they were going to shine a light for the common man, but they were interested in serving the public, so I felt like, it’s our story, too. It’s the story of these elite men, but it’s also the story of how all of us, middle-class Americans, came to tell stories about the world in the way that we do. How we came to be so interested in the news, how we came to consider the news a form of entertainment.

Also, it’s the story of the rising middle class. We can look back on that period of American history and it always impressed me when I started reading the letters that people from the Midwest and the Western states would write Time; Hadden was shocked when he started receiving these letters. Oh my God, people are actually reading this thing we’re putting out. And not only reading it, but they were learning from it, they were attracted by it, they were beginning to write in his style in order to imitate him and join the elite circle of the young and the urbane. So that impressed me: the fact that the middle class of the 1920s was so upwardly mobile. It seems like something we’ve lost.

Truthdig: What do you mean by that?

Wilner: It seems like people today don’t want to learn all the news from around the world. We have so many entertainment options, and we’re reading the news all the time; we’re just inundated by information, and so it doesn’t seem as though the middle class today is as eager to climb upward and belong in American society.

That was a remarkable aspect of the 1920s. Film was new, radio was new, fashions were spreading, and a national conversation was just beginning to take place. And all across America, people whose parents had grown up on the farms, people who were the first in their families to attend college, wanted to join this conversation. They wanted to know what was happening in the world, and Time was an easy place where they could figure it all out quickly. It was a way for upwardly mobile people to become more knowledgeable and sophisticated than they were.

Today, the middle class seems downwardly mobile. For example, we frown on intellectualism. Presidential candidates would never want to appear intellectual. Whereas at that time, people wanted to be intellectual. And that’s why they liked Time, because it was fairly easy reading, but they would always learn something: a new word, they would get out their dictionaries to learn words Hadden was using. Can you imagine? They used the dictionary. We don’t do that today. It was the birth of a national literary culture.

Truthdig: Your book is predicated on the fact that what Time did was very significant for modern journalism. But your book is also coming out at the very moment when many people are questioning the relevance of a newsweekly in the age of the Internet. Was that a concern?

Wilner:

The parallels are striking. I always think of Time as the Google of its time. Time was the one company that put all of the facts you needed to know at your fingertips. That’s what Google is trying to do today. But Google has cut out the filter. They’re not digesting the news. Americans definitely still need a digest, we definitely need a trusted filter to tell us what’s true and what’s not, but the question is whether we want it. More and more, many people just want to receive the news that interests them, the stories that entertain them, and opinion pieces that they agree with. So Time came out of a different era, when it wasn’t possible to filter out the news for yourself. But now that we can do that, there’s a danger that we’re losing that national hearth, the one place we can all congregate and hear the same story. It’s not just the news magazine, it’s: Is there a place for the evening news? Or is there a place for big-budget movies that everyone goes to see, that are still good movies?

So it does seem as though America is no longer united by a national story line, except for one thing: 9/11. We’re pulled together by the most epic and tragic event that defines our time, but other than that, our country is pulling apart. We’re all running in different directions. It’s a scary thing. And this is what Hadden was inspired by: Hadden was inspired by Homer and the idea that the Iliad, because it personified the past, the epic past of the Ancient Greeks, it was the national story line. Parts of the story would be related orally around a campfire, and that’s what Hadden wanted to become: a bard for our time — someone who could almost sing to this country the history of the nation. We’ve lost our ability to do that.

And what I’m trying to do is to still make an academic contribution, still bring forward original research, but tell it in a way that can reach everybody. Because I think we need books, magazines and TV shows that bring everybody together and sing the big themes.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

“The Man Who Time Forgot”

“The Man Who Time Forgot”

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.