The Battle Over Ethnic Studies in California

Artists and poets are fighting to keep the Mexican-American experience in curricula across the state. Commuters at Los Angeles's Union Station under the mural "City of Dreams/River of History" by artist Richard Wyatt. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)

Commuters at Los Angeles's Union Station under the mural "City of Dreams/River of History" by artist Richard Wyatt. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)

An intellectually curious kid, Matt Sedillo was obsessed with the U.S. presidency. By the time he was five, Matt had memorized the names of every American president. When he was seven, stuck in gridlocked Los Angeles traffic one afternoon, Matt told his father David that he wanted to be president of the United States when he grew up. The smart East L.A.-born dad turned to his smart son.

“You can’t be president.”

“Why, Dad?”

“Because you’re Mexican.”

Sedillo didn’t become a POTUS, but he did become a poet and activist leader committed to remedying racist structures that made his American father believe his American son couldn’t grow up to hold America’s highest office.

Strategically attacking complex problems like systemic racism, the school-to-prison pipeline, the erasure of the histories of people of color and anti-immigrant xenophobia requires creative thinkers who can creatively problem-solve. Politically minded artists often have skill sets tailor-made for social justice leadership — and poets especially. We tend to be good communicators. We understand how words can move people into action because we often craft language aimed at the heart. Many poets have practice speaking truth to power. And we often have a long history of inspiring others to do the same, which makes us dangerous.

“Beware of artists, they mix with all classes and are therefore dangerous for they move in all classes,” Sedillo told Truthdig, quoting Queen Victoria. “My poetry is most influenced by political speeches. It’s a political rhetorical style. I studied Cesar Chavez and Malcolm X and tried to incorporate their style into my poetry.”

In the context of racially and politically motivated anti-Brown sentiment and policies, Sedillo’s work explores the possibility of poetry functioning both as art and political discourse — the intention of which is to move people into political action. Author of 2022’s “City on the Second Floor” and literary director of the Mexican Cultural Institute of Los Angeles, Sedillo led a Mexico City delegation of artists, activists and scholars to UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico, one of Latin America’s top universities) in November of last year, to address sociopolitical issues impacting Mexicans on both sides of the border.

Chicano performance artist, scholar and activist Elias Serna — the co-founder of Chicano Secret Service, a politically-engaged performance art group — shares Sedillo’s blending of art and activism. Over the past decade, Serna has been one of the most effective grassroots activists fighting for ethnic studies requirements in California schools. Gov. Gavin Newsom signed 2020’s A.B. 1460 requiring all California State University students, beginning in 2025, to take an ethnic studies course in order to graduate. He also signed 2021’s A.B. 100 requiring all California high school students, beginning in 2030, to take an ethnic studies course in order to graduate.

Reflecting on these victories, Serna told Truthdig that activist art was critical in being successful in this tough political environment. “Through art, you can reach people at a much deeper level than political talking points because people are more open to hearing what you have to say,” he said. “We know the arts have their own spiritual power and this is the type of power that was needed in the fight for the ethnic studies requirement because so many forces around the country are trying to ban teaching Chicano history.”

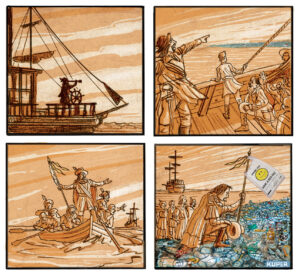

Serna cut his teeth in the ethnic studies fight by organizing artists and activists to travel to Arizona after Gov. Jan Brewer signed 2010’s H.B. 2281, banning Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican American Studies (MAS) program — even though one study found dramatic improvements in educational outcomes for MAS students. The 53,000-student school district was 60% Latinx. At the time, Maria Therese Mejia, a senior at Tucson High Magnet School told CNN, “I feel really disheartened. Those are our history (books), you know? It’s ridiculous for them to be taking away our education. They’re taking (the books) to storage where no one can use them.”

Seeing the educational attack on Mexican children up close — especially the banning of Chicanx books — was a powerful experience for Serna. Thinking outside the box while working with fellow artists and activists, he created Chicanx history pop-up books. The three-dimensional books were a creative way to encourage the devastated Chicanx students and a nontraditional way to engage Chicanx adults who wouldn’t necessarily pick up banned MAS books like Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed.”

“We know the arts have their own spiritual power and this is the type of power that was needed in the fight for the ethnic studies requirement because so many forces around the country are trying to ban teaching Chicano history.”

Elias Serna

“Creating the Chicanx history pop-up books really lifted everyone’s spirits,” he said. “We made and distributed hundreds of these books and taught workshops so other people could learn how to make and distribute them in their own communities. Not only were they educational, they were accessible. We used to say, ‘You can ban Chicanx books but they still pop up!’”

Serna, who now has a Ph.D. in English literature and teaches ethnic studies at Santa Monica College, said one of the primary personal benefits of fighting for ethnic studies has been that it’s taught him to listen closely to younger activist artists like Sedillo, who’s a friend and colleague.

“I love talking to Matt because he’s a force of nature,” Serna said. For me, listening has become a muscular activity because it’s how I grow. There needs to be an intergenerational component between activist artists so we can continue to share resources and sharpen our skills. Activist artists like Matt and I have a vision. Our leadership approaches are less constrained by tradition and protocols, so we are more agile in our response to white supremacy.”

UC Berkeley’s Latinx Research Center has invited Serna to discuss how pop-up books figure in his activist leadership approach, in a March 23 event titled “You Can Ban Chicanx Books But They Still Pop Up!” In the continuing context of banned ethnic studies texts, he’s excited that these nontraditional activist books are still resonating with audiences. Serna said it shows the power of art when merged with activism.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.