Take, Don’t Make!

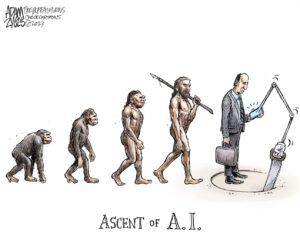

How did two hedge funds that have fewer than 100 employees each make as much money as Apple Inc., which relies on the hard work of its nearly 30,000 U.S. employees and an additional 700,000 workers and contractors globally?

By Les LeopoldThe following is an adapted excerpt from Les Leopold’s new book: “How to Make a Million Dollars an Hour: Why Hedge Funds Get Away with Siphoning off America’s Wealth” (John Wiley and Sons, 2013). It is reposted here with permission.

While researching, “How to Make a Million Dollars an Hour: Why Hedge Funds get away with siphoning off America’s Wealth” (John Wiley and Sons, 2013), I stumbled upon these stunning factoids:

• In 2009, David Tepper, the head of the Appaloosa hedge fund, earned an astounding $4 billion. Personally. (That’s $1,923,076.92 per hour.) • The following year, John Paulson of Paulson and Co. broke Tepper’s record, hauling in $4.9 billion, or $2,355,769.34 per hour! • Each firm reportedly earned around $20 billion. • More amazing still is that they earned these enormous incomes during the two most horrific economic years since the Great Depression—and they did it with only a skeleton crew.

So, here’s the real puzzle: How did these two hedge funds, which have fewer than one hundred employees each, make as much money as Apple Inc., which relies on the hard work of its nearly thirty thousand U.S. employees (and the incredibly hard work of another seven hundred thousand workers and contractors globally)?

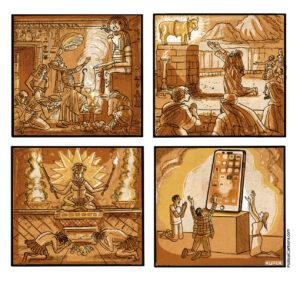

Hint: Produce nothing tangible for the real economy. Don’t waste your time inventing or manufacturing stuff. In the hedge-fund game, you don’t make—you take.

And for good reason. Making things or providing services to large numbers of people is a complicated business. You have to have a marketable idea, probably a brilliant one. You have to hire workers. You have to manage them. (You may even have to deal with a union, God forbid.) You need to build a spirit of cooperation and a culture that values high quality and customer service. And don’t forget the R and D you’ll need to keep the innovation flowing. Of course, you also have to compete in a crowded global marketplace, create an entirely new niche, or both. It’s the kind of work that keeps you up at all hours. The sweat in sweat equity is real. No way do you want to go near this game when you could run a hedge fund instead.

Better to enter the mystical world of money managing, as described by Daniel A. Strachman, who has written several informative books on hedge funds. He believes that hedge-fund managers deserve to make so much with so little labor because they are simply more brilliant than those plebeians who worry about making cute little gadgets. Strachman is absolutely awed by hedge-fund billionaires:

“These individuals are some of the brightest investment managers of all time, possessing unique skill sets that have made them extremely successful at managing money and exploiting market opportunities…. In essence, they are capable of seeing the markets in ways that most of us simply cannot imagine, and it is this rare vision that allows them to determine whether opportunities have value, thereby creating infinite windows to make money. That is what makes them great hedge fund managers.” (Strachman 2008, 16)

I have no doubt that these hedge-fund guys are very bright fellows and that the ones who make it to the top possess intelligence, foresight, and obscure knowledge. But really, are these hedge-fund guys so much brighter than those who create and manufacture everything we use? Is their “rare vision” so superior to that of the late Steve Jobs and his associates? And just what are those “infinite windows” that “most of us simply cannot imagine”?

We all know how Apple earns its keep. It invents, manufactures, and markets products that the world voraciously consumes. (It also profits by using regimented workers in China who live in company dorms, wear identical company uniforms, get paid little, and work around the clock whenever Apple needs them.) The iMac, iPod, iTunes store, iPhone, and iPad have driven Apple’s net profit from $4.8 billion in 2008 to $8.2 billion in 2009, to $14 billion in 2010, and a stunning $26 billion in 2011.

Meanwhile, Tepper’s Appaloosa hedge fund probably took in $20 billion, racking up an incredible 117 percent return for its investors in 2009. Doing what, exactly? Where’s their iPad?

Here’s what the financial website HedgeFundBlogger.com says about how Tepper made his billions:

[Tepper] did so by betting that the recession would not last as long as many analysts and public officials predicted and taking big stakes in struggling firms like Bank of America and Citigroup. Tepper understood that the government would not nationalize these banks and when many were unsure of the two banks’ futures his fund was buying up shares which he believed were significantly underpriced. By purchasing these shares and stakes in other smaller banks and financial lending institutions, Appaloosa Management LP was able to turn a $6.5 billion profit in 2009.

“It was crazy,” says Tepper, a Pittsburgh native. “In February and early March, people were in a panic.” (Wilson 2010)

If this report is correct, Mr. Tepper made almost as much as Apple by betting that we taxpayers would bail out, but not nationalize, Bank of America and Citigroup. And, of course, we did. Citigroup got the Federal Reserve’s rock-solid guarantee for more than $300 billion in toxic assets then rotting on the company ’s balance sheet. Without our bailouts, both banks would have folded—and a slew of other banks and hedge funds would have toppled like dominoes. (These two banks also took advantage of billions of dollars in hidden Federal Reserve loans provided at negligible interest rates.)

Yet Tepper was also shrewdly betting that the government would never play hardball with the big banks. Washington, he sensed, would not nationalize these failing banks, a move that would wipe out its shareholders. No, he saw that the political establishment was too afraid of another Great Depression—and of spooking global markets—to risk letting the big banks fail. Besides, the government’s perceived interests had become completely entwined with Wall Street’s. The revolving door between Wall Street and Washington was spinning fast, with all of the key economic positions in both the Bush and the Obama administrations held by Wall Streeters. These high finance recidivists temporarily running the government shared the same worldview as their Wall Street colleagues: big banks should not be nationalized. Instead, as Tepper apparently guessed, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson (under Bush) and then Timothy Geithner (under Obama) would put the power of the government behind those banks so that they could go back to making sizable profits for their shareholders, who would be protected and bailed out.

As Tepper noted, many other investors panicked, either because they did fear nationalization, or because they’d been forced to sell securities to raise cash and cover other losses. Those wary investors dumped their banking securities, creating a delicious buying opportunity for Tepper. He jumped in with both feet.

Ironically, Tepper was betting against free market ideology, which preaches that you’re rewarded when your investment succeeds and punished when it fails. When investments succeed, shareholders are rewarded with dividends and rising share prices. When they fail, shareholders lose their money.

Citigroup was a financial toxic dump in the fall of 2008, and Bank of America wasn’t far behind. Under idealized “free market” capitalism, both banks would have gone under, entirely wiping out shareholders’ equity. Bondholders probably would have received pennies on the dollar for their loans. Too bad. To paraphrase the drunken baseball manager played by Tom Hanks in the movie “A League of Their Own,” there’s no crying in capitalism.

Tepper’s big bets suggest that he knew this quaint form of capitalism was long gone. So, while most investors were fleeing financial stocks in terror, Tepper had the cojones to buy them up cheap. Cojones—literally. According to the Wall Street Journal, Tepper “keeps a brass replica of a pair of testicles in a prominent spot on his desk, a present from former employees. He rubs the gift for luck during the trading day to get a laugh out of colleagues.” (Zuckerman 2009).

Tepper reminds me of George Washington Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, who also had cojones. Said Plunkitt in 1905:

There’s an honest graft, and I’m an example of how it works. I might sum up the whole thing by sayin’: “I seen my opportunities and I took ’em.” Just let me explain by examples. My party’s in power in the city, and it’s goin’ to undertake a lot of public improvements. Well, I’m tipped off, say, that they’re going to layout a new park at a certain place. I see my opportunity and I take it. I go to that place and I buy up all the land I can in the neighborhood. Then the board of this or that makes its plan public, and there is a rush to get my land, which nobody cared particular for before.

Ain’t it perfectly honest to charge a good price and make a profit on my investment and foresight? Of course, it is. Well, that’s honest graft. . . .

It’s just like lookin’ ahead in Wall Street or in the coffee or cotton market. It’s honest graft, and I’m lookin’ for it every day in the year. I will tell you frankly that I’ve got a good lot of it, too. (Riordon 1905, 9)

Let me make this perfectly clear to any litigators present: I am not suggesting that Tepper traded on insider information about impending government moves or that he received any “graft” of any kind. (You’re not going to make your next million off me.) I’m only saying that like Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, Tepper knew that business and government were of a piece. So when, on cue, Washington came to Wall Street’s rescue, Tepper cashed in on his bet. That’s how he alone earned almost as much in one year as Apple and its tens of thousands of employees did. Does that mean Tepper has our bailout money in his pocket?

Indirectly, yes. By buying shares of Bank of America and Citigroup, Tepper became a part owner. Fine and dandy. But his shares had real value and gained in value only because of the billions in federal cash, the billions in federal asset guarantees, and the billions in cheap federal loans those banks collected from taxpayers.

We didn’t write a check and put it in Tepper’s pocket. We didn’t have to. He just “seen [his] opportunities and . . . took ’em.”

The key point to remember is that if Tepper had bet wrong and the Fed hadn’t ridden to the rescue, then his hedge fund—and most hedge funds—would have lost billions. In fact, the bailouts saved the entire hedge-fund industry from utter collapse.

All of this suggests so far that most hedge fund money is made fair and square — buy low, sell high. But as the rest of this book shows, we should cast a much more critical eye on how such outrageous incomes are amassed. We will discover again and again that it really pays to place big bets when you already know the outcome. Some of these techniques are legal, some barely legal and many violate the law. It turns out that many, many hedge funds are ethically challenged. In fact, Preet Bharara, the U.S. attorney who is investigating hedge fund insider trading has said that the entire industry may be operating from a “corrupt business model.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.