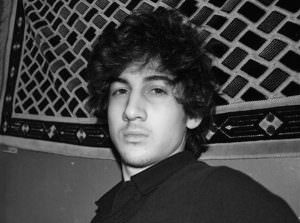

Stop Assuming the Boston Bomber Is a Muslim

The first tweet I saw when I checked my Twitter account Monday afternoon was a one-line plea: "Please don’t let it be a 'Muslim.'"

The first tweet I saw when I checked my Twitter account Monday afternoon was a one-line plea: “Please don’t let it be a ‘Muslim.'”

That’s how I knew something terrible had happened. Not long after, the hashtag “Muslims” was trending worldwide on Twitter. Press releases from local and national Muslim organizations began to appear in my inbox within two hours of the explosions that devastated the Boston Marathon on Monday.

“MPAC Condemns Heinous Terror Act,” read an email from the Muslim Public Affairs Council. “This is a horrible crime, and we call on all of us as Americans to work together to bring those responsible to justice.”

And then another email, this one from the Council on American-Islamic Relations’ Nihad Awad: “American Muslims, like Americans of all backgrounds, condemn in the strongest possible terms today’s cowardly bomb attack on participants and spectators of the Boston Marathon.”

If this feels familiar, it’s because it’s become routine. This is modus operandi for any Muslim organization in the U.S. after a terrorist attack: condemn, condemn, condemn. This is how we’re expected to respond. It doesn’t matter that no Muslim or Arab has been implicated in the attack. It is inconsequential that no other religious organizations are called on to do the same. In a post-9/11 world, Muslims and Arabs have become the default scapegoats for all terrorist plots, hence the pre-empting of the accusations.

But it isn’t as if the protestations of Muslims have done any good. In the absence of information and facts, political pundits resorted to xenophobic speculation. Take conservative columnist and occasional Fox News guest Erik Rush, for example. Rush helped fuel the trending hashtag “Muslims” after he tweeted, “Everybody do the National Security Ankle Grab! Let’s bring more Saudis in without screening them! C’mon! #bostonmarathon.” When a Twitter user asked whether he was already blaming Muslims, Rush replied, “Yes, they’re evil. Let’s kill them all.” The tweet went viral, exposing Rush to an entire section of social media users who do not find genocidal jokes funny. Eventually, he deleted the offending tweets but continued to defend himself against “Islamist apologists.”

Another example is the news media’s rabid response to a New York Post story Monday that claimed the FBI had a Saudi national in custody as a “person of interest” in the Boston blasts. The man was reportedly seen running away from the explosions and tackled to the ground by a civilian who thought he looked suspicious. A Boston Police Department spokesman, however, denied the Saudi man was being detained.

“Honestly, I don’t know where they’re getting their information from, but it didn’t come from us,” he said.

On Tuesday, U.S. law enforcement officials clarified that the Saudi national in question was a witness and not a suspect.

That, however, may still not be enough for people like Rush, for whom Arabs and Muslims will probably always be suspect. Whether it’s the color of our skin or the way we dress or the God we believe in, Arabs and Muslims will always have an air of suspiciousness. This is the reason we cannot pray in airports or wear religious clothing to work or take the subway without being implicated in some imaginary plot. It’s why our first thought after an attack is “I hope they aren’t Muslims,” and why we aren’t given an opportunity to mourn and grieve like the rest of the country. It’s why we feel compelled to condemn the crimes of madmen.

It’s also why I didn’t want to leave the house Monday after news of the bombings broke. My headscarf felt like a target on my back. My dark tan seemed like an incrimination. This is how it feels to be choked by systematic racism. This is how it silences you. Collective guilt and punishment are racism’s most loyal henchmen.

If this sentiment sounds familiar, it should. Seventy-one years ago this month, in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor during World War II, the U.S. Army established the Wartime Civilian Control Agency to direct the forced evacuation of Japanese-Americans to “relocation centers” like the one in Manzanar, Calif. The Manzanar camp contained 445 barracks and could hold as many as 10,000 people. On April 17, 1942, the War Relocation Authority also leased property from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to serve as one of two West Coast reception centers.

Manzanar is now a historical site, and the Manzanar Committee organizes yearly pilgrimages every April to the cemetery there to honor those incarcerated and remember this great stain on the scroll of U.S. history. But forgetting is easier. Shortly after 9/11, Peter Kirsanow, a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, suggested that if attacks by terrorists who were Arab continued, “not too many people will be crying in their beer if there are more detentions, more stops and more profiling.” Two years later, conservative author and Fox News contributor Michelle Malkin wrote a book called “In Defense of Internment.” The title is self-explanatory. Suddenly, Manzanar didn’t feel so far away.

It does appear, however, that things are not as bad now as they were in those first heedful years after 9/11. For example, on Monday night the “Muslims” trending topic on Twitter was overwhelmed by people who rushed to the defense of Muslims. And Rush’s comments were vehemently condemned until he was compelled to delete them. These are edifying moments and they unite us in favor of a more common good.

I don’t want to live in fear, not of ambiguously drawn terrorist bogeymen, nor of my own countrymen. Fear foments hate and if Monday’s bombings were not the manifestations of unbridled hate than they must have been the products of madness. I hope whoever carried them out isn’t Muslim, but if they are, I wish it won’t matter.

Tasbeeh Herwees is a freelance writer and producer in Los Angeles. She is also the co-founder of Kifah Libya, an independent, online magazine about Libyan political, social and cultural affairs.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.