Soup Having Sex With Soup

"If only we could pull out our brain and use only our eyes," Picasso said, naming the distinct advantage that artists have always had over pundits and polemicists when it came to perceiving the world as it is; pundits and polemicists being much more likely to insist that the world is whatever a person wants it to be."If only we could pull out our brain and use only our eyes," Picasso said, naming the distinct advantage that artists have always had over pundits and polemicists.

“I’m afraid that if you look at a thing long enough, it loses all of its meaning.”

–Andy Warhol

Bill Hicks, arguably the most existentially articulate comic id of the late 20th century, had a bit in his act where he talked about the bias that the news media had against illegal drugs; illegal drugs, of course, being a metaphor for anything that existed outside the miasma of mainstream influence and wasn’t directly controlled by elite institutions of corporate and state power. Pretending to be a television news anchor reporting on hallucinogens without prevarication, Hicks said, “Today, a young man on acid realized that all matter is merely energy condensed to a slow vibration — that we are all one consciousness experiencing itself subjectively. There is no such thing as death, life is only a dream, and we’re the imagination of ourselves. Here’s Tom with the weather.”

What I appreciate about that quote is how it forces a person to consider the context wherein a concept of truth is typically placed for public consumption. Like all good satire, it illustrates just how insular and self-serving every hard-boiled notion of reality can become once it’s dropped into the confused bowl of electrified noodles that is the human brain, an organ famous the world over for its uncanny ability to acquiesce to whatever real or imagined authority it perceives to be blowing through the room at any given moment. How many of us, for example, have walked through the reptile house at the zoo and stopped to press our face against the glass of a terrarium and looked at the lizard lying as still as a root cresting the ground in the corner and thought that the cheesy landscape painted on the rear wall of the tank, along with the Sherwin-Williams sky and the Exo Terra Repti-Glo 10.0 Compact Fluorescent Desert Lamp pretending to be the sun, was enough to convince the captive animal that it was at home in the vast grasslands of Southern Australia? All of us have, of course, and not because we are too stupid to see through bullshit but rather because we like to think that the world is being managed by other people who know more than we do about all the complicated and boring crap that we don’t want to waste our time thinking about. When we imagine that there are other people in the world burdened with the responsibility of not letting bullshit run amok, we succumb to the illusion that we are being protected and shepherded along by a wisdom that isn’t really there.

I found myself thinking about all this in New York City last month during the Occupy May Day protests, which had started early in the day at Bryant Park before moving south, like a transient Renaissance fair that had been purged of its whimsy, its Elizabethan English and its haggis and transmogrified into a pagan celebration of workers’ rights, mass dignity and First Amendment Tourette’s, toward Wall Street. I had just stepped away from the likeminded riffraff in Union Square Park, having grown a bit woozy from breathing in the intoxicating fumes of the movement’s jubilant upset for the better part of the afternoon, when I found myself standing at the concrete base of the chrome statue of Andy Warhol, aptly named The Andy Monument, that faces the park at 17th Street. Looking up at this Gandhi of Self-Commodification, this Horace Pippin of Madison Avenue, his trademark Polaroid camera hanging from around his neck like a mystic’s third eye, his Bloomingdale’s shopping bag, according to the sculptor, Rob Pruitt, weighed down with copies of Interview magazine, I noticed that he was gazing at the protesters in the park, no doubt considering their collective aesthetic and not giving a tinker’s damn about the content of their cause.

To him, I imagined, the congregation of complainers, myself included, was little more than a nomadic audience that had arrived in Union Square to enjoy the only entertainment available to it, which was theater of the mind, the star billing going to the holy ghost of communal optimism with doomsday as its understudy. Or maybe it was more personal than that. Maybe he was watching carefully to see who might emerge from the crowd as a beautiful misfit among misfits; a waifish boy in neon lipstick, perhaps, his upper arms as skinny as bruised bananas, or a girl of 16, a runaway for sure, her hair teased into brittle pink Easter grass and mascara smeared hard across the back of her hand, a perfectly chic junkie to brand back at the Factory for resale — fuck the agony of the 99 percent!It was most definitely a curious sort of apathy for me to imagine coming off an inanimate object. Odder, still, was my ability to forgive the apolitical broad view emanating from The Andy Monument, to even sympathize with it, particularly after I’d spent the previous eight months creating artwork for the OWS movement, arguing in print and on the radio and at public speaking events for its relevancy and hating those who predicted and prepared for its demise with relish. These saintly and determined Occupiers were, in fact, dear comrades with whom I’d shared weed and canteens and long embraces, all of us jeering so intensely at the innumerable garrisons of uniformed cops surrounding us since the fall that no one in a uniform — mailmen, bus drivers, doormen, nobody! — was safe from contempt in our peripheral vision anymore.

So why now, in this moment, while standing next to a chrome aberration of Andy Warhol, did my fellow hell-raisers suddenly look like strangers to me? Was it a crisis of faith or was it, perhaps, because they really were strangers?

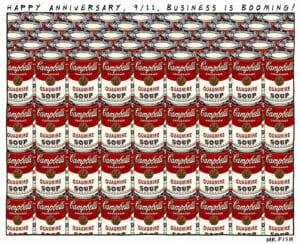

“If only we could pull out our brain and use only our eyes,” Picasso said, naming the distinct advantage that artists have always had over pundits and polemicists when it came to perceiving the world as it is; pundits and polemicists being much more likely to insist that the world is whatever a person wants it to be, as if reality, itself, were there only to corroborate a person’s completely egocentric opinion — political, religious or otherwise — about everything and everybody. Artists tend to have an instinctual understanding that reality is much more self-referential than needing to be labeled by a human brain to be relevant and that the meaning of an object has very little to do with the abstract counterpart that people carry around inside their heads, human consciousness being so much more comfortable sculpting putty than stone. I thought about Warhol’s famous silk-screens of soup cans and how they were never interpreted as ads for soup, for instance. I thought about his silk-screens of the electric chair, how they were never mistaken as commentary either for or against capital punishment. I thought about his silk-screens of Marilyn Monroe and how they were never considered glamorous portraits of feminine beauty.

I thought about how, contrary to his reputation, Warhol’s genius had to be his ability to deflate the importance of commercialism and celebrity in the American consumer culture, to rob it of its cheap superficiality by destroying its ability to speak for itself. By killing the language with which mediocrity finds its voice, there will be nothing left but the aesthetic element of BEING to consider.

“Excuse me,” said a tattooed girl in pigtails holding out a digital camera to my left. She was standing with what I guessed to be her boyfriend, who had intensely green eyes and a beard like Rasputin, both wearing backpacks and appearing several days out from their last shampoo and gargling. “Can you take for us our picture?” she asked, her German accent making her words sound as if they were being hatcheted into a wet log.

“Sure,” I said, taking the camera. “Where do you want to be?”

“Here,” said the girl, leading me around to the other side of the Warhol statue where she and her boyfriend took up position in front of a long line of riot police on scooters. With their arms around each other and huge smiles plastered across their faces, they could have been in front of Niagara Falls or on the west rim of the Grand Canyon or, given the stone cold seriousness chiseled into the faces of the cops behind them, Mount Rushmore. What I knew for certain was that they were standing in front of the country’s newest attraction. What I also knew was that it was on a national tour, soon to be available everywhere, which somehow cheapened my involvement in it. Handing back the camera and wishing the couple well, I looked over my shoulder at the Andy Warhol statue and tried to see myself in its completely reflective surface, surprised to find nothing of legible consequence staring back at me. Then, looking across the street and watching the grubbiest Santa Claus imaginable prance about on tiptoe among the demonstrators, his glee as bullying as a Bull Connor fire hose, his ceaseless merriment as he danced around with a filthy cardboard speech bubble containing the words “not me” attached to the end of a 10-foot wand, which he tried to force into the face of anybody who came near, I readily admitted that, without a doubt, I would be the first to look away and rock back and forth on my heels if any of the riot police crowded around Union Square decided to draw their batons and make a running tackle.Deciding that it was time for a piss break, a quadruple espresso and a free Internet connection so that I could check my emails, I tromped off in the direction of one of the three Starbucks that I knew to be in the area, not knowing of a decent mom and pop place anywhere in a 10 block radius. Stopping at the corner of Park and 17th, I watched as a passing car threw an empty soda can at a scruffy-looking kid with an unlit cigarette in his mouth who was holding a gigantic piece of lime green poster board that read “Economic justice for all!” “Get a fucking job!” shouted the driver as he went by, completely missing the irony of having just directed his rage toward somebody hoping to save the world, not with anarchy or free love, but with a plea for gainful employment and a living wage.

This wasn’t Mario Savio addressing Berkeley through a bullhorn. It was Ward Cleaver counseling Beaver on the merits of following the American dream.

“You all right?” I asked the kid, once I crossed the street. He nodded without smiling and asked me whether I had a match. “A what?” I asked.

“Fire,” he said. “A torch!”

I told him that he shouldn’t smoke. He told me I shouldn’t be such a fucktard. I didn’t say anything and walked past him, once again doubting the sincerity of my devotion to the idea that the future could and should be brighter. How, I wondered, was I supposed to believe that this Occupy May Day protest was any different from any other mass gathering, whether it was a tea party rally or a church revival or a “Star Trek” convention? Didn’t each configuration represent a venue where one simply put on a costume to camouflage his or her social awkwardness and hard-boiled dissatisfaction for the here and now, and safely channel his or her own inner Spock, Ted Nugent, Jerry Falwell or Che Guevara, the moral certainty of each participant made to seem incontrovertibly true by an attendance count, the mathematics of fandom always trumping the questionable integrity and practical application of the agenda being rallied around? After all, this kid’s sign — this idiot’s sign! — was demanding fairness from an economic and political system controlled by private owners for profit. I wanted to go back and ask him why he wasn’t holding up a sign asking that the NFL be made more fair for players by eliminating the need for a scoreboard and giving everyone equal possession of the ball, but, honestly, I didn’t have the energy.

Twenty minutes later I was back in the park with my fist in the air and a renewed bloodlust surging through my veins. Having discovered that all the Starbucks in the area had kicked out their patrons after lunchtime and locked their doors to everybody but the police — police who I could see through the glass in their jackboots and leather gloves and sunglasses, sipping frothy drinks and eating pound cake, their helmets and shields resting on the tables, great lassos of plastic handcuffs looped through their belts like trash bag ties — I was reinvigorated to loot the rich folks’ house on the hill, burn the drapes, impregnate the dog and smash the chandeliers into pixie dust.

Fingering the unspent coffee money in my pocket, I felt thankful for the distraction of having all the other protesters around me, for without them I might’ve had the wherewithal to properly diagnose the source of my rage and recognize it as being something less than revolutionary.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.