SAG-AFTRA’s New Contract Falls Short on AI

Critics fear that weak language and loopholes on artificial intelligence could impact disadvantaged actors first and hardest. A striking SAG-AFTRA member holds up a sign in a picket line outside Walt Disney Studios, Friday, Oct. 20, 2023, in Burbank, Calif. (AP Photo/Chris Pizzello)

A striking SAG-AFTRA member holds up a sign in a picket line outside Walt Disney Studios, Friday, Oct. 20, 2023, in Burbank, Calif. (AP Photo/Chris Pizzello)

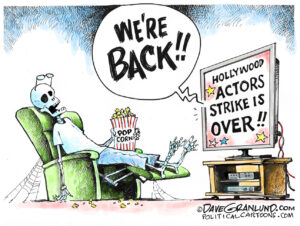

After 118 days on strike, the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) board voted Nov. 8 on a tentative new contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) by a majority of 86% to 14%. After sending ballots to its 160,000 members over the past few weeks, voting on the contract wrapped on Dec. 5.

The tentative end to the strike came on the heels of the successful negotiation of a new contract for the Writers Guild of America (WGA), who voted 99% to ratify the new contract after WGA leadership voted unanimously to accept it.

The end of the long strike season was a relief for the actors’ union. According to SAG-AFTRA, “the revolutionary gains achieved in these contracts are projected to generate more than $1 billion in new compensation and benefit plan funding.” This would include pay increases for many principal actors and background actors, huge gains in pension and health contributions, and other wins like streaming bonuses and higher residual payments.

Miriam Blanco, an actor and SAG-AFTRA member based in Los Angeles, said she feels “pretty positive” about the deal. “We could have come away with a lot less,” she said.

AI usage, particularly what the contract calls generative AI, could threaten to undo inroads made in diverse storytelling in Hollywood in recent years.

But not everyone is happy with the outcome, particularly regarding the contract’s stipulations around the use of artificial intelligence, or AI, and its broad-reaching implications for actors. While the tentative contract includes regulations requiring producers to get actors’ consent to use their likenesses for AI, some are concerned that the language is too weak and the loopholes too broad to protect them.

AI usage, particularly what the contract calls generative AI, could threaten to undo inroads made in diverse storytelling in Hollywood in recent years. Reports of racial, ethnic, and gender bias in AI are rampant, and its proliferation could perpetuate stereotypes about marginalized groups, take jobs from working actors, and upend entire genres and subfields, such as voice acting, animation, and stunt acting. Some fear it could eventually lead to the end of the industry as we know it.

The contract divides artificial intelligence into several categories. The first is what’s known as an “Employment-Based Digital Replica,” which is based on an actual human actor. According to Melissa Medína, a SAG-AFTRA member and voiceover actor based in the Minneapolis area who is knowledgeable about AI from their previous work in the tech field, an example of this could be a video game character based on scans of a person.

The contract establishes that creating an Employment-Based Digital Replica requires producers to give actors 48 hours notice, obtain “clear and conspicuous” consent from actors to use their likeness, and pay them for it. In many cases, that consent “shall continue to be valid after the performer’s death unless explicitly limited otherwise.”

Critics of the deal who spoke to Prism were most concerned about the sections on generative AI, which is used to create ”synthetic performers” or “digitally-created asset[s]” that are not any specific human performer but generated entirely through AI. This is uncharted territory. SAG-AFTRA member, actor, and director Satu Runa in Los Angeles believes the union should have stood against its use, period, rather than trying to “work with” it.

“It’s very easy to replace us with this technology,” she said. “We shouldn’t normalize it.”

The protections also include some significant loopholes. For one, for AI involving the participation of human actors, Schedule F performers, who make more than $80,000 for a film, are exempted. And consent is not required from actors if the photography or soundtrack remains “substantially as scripted, performed, and/or recorded.” Prior consent given can apply to future features if the producer includes a “reasonably specific description of the intended use,” language that could be interpreted broadly by producers.

The contract also doesn’t protect against retaliation in the hiring process for not giving consent. “Actors, and young actors, or desperate actors who want to work … they’re gonna feel the pressure to just check the box,” Runa said.

As Kate Bond, a SAG-AFTRA actor and strike captain who planned to vote against the deal, put it: “they forgot to put protections in the AI protections.” She noted that unlike the WGA deal, where union members came to the table with the explicit position that “writers are people,” the SAG contract falls short of making such a stance.

And if digital likenesses are used without an actor’s consent, they are entitled to arbitration, but remedies are “limited to monetary damages,” she added. This doesn’t say that producers would then need to remove the actor’s data from wherever they store it. They could just pay damages and continue using it, Bond said.

As Medína noted, there is also little information about where data of actors’ likeness will be stored, if consent can be revoked, and how servers would even technologically be capable of removing data once it is uploaded.

Information used to create digitally altered synthetic performers could come from amalgamations of different actors’ features, voices, and movements. “All it takes is a prompt to smash together six or seven different actors and create one uber-actor,” Medína said. This would make seeking compensation for use of your physical features, voice, or movements nearly impossible, especially for actors who aren’t recognizable.

The contract also doesn’t protect against retaliation in the hiring process for not giving consent.

Finally, both Medína and Bond are worried about language that says the definition of “Synthetic Performers” does not include “non-human characters,” and therefore stipulations around consent may not apply to them. Producers could conceivably expand “non-human” to include not only CGI creatures or animals, for example, but also any animation or anime, or “humanoid” characters like superheroes. This could ultimately replace huge parts of the industry with AI. In the shorter term, voice-acting, stunts, and dubbing work as we know it could disappear, warned Medína.

“With things like generative AI, there’s no more need to engage the everyday working actor, folks like myself, who work as actors full time, who aren’t recognizable. And a lot of those folks are often people of color,” said Medína, who is Latinx and Indigenous.

As it is, AI poses disproportionate dangers for people of color and other marginalized groups.

“There are so many biases with AI that physical representations of ethnicity will become extremely problematic,” Medína said. For example, last month, the Taiwanese-American model Shereen Wu accused a major designer of altering her images so she appeared white.

Short of that, Blanco, who is disabled, worried that there are “individuals and companies that are going to try to use [AI] as a shortcut to check a box of representation.” Earlier this year, Levi’s launched an ad campaign featuring supposedly diverse models, some of whom had been generated by AI.

Bond agreed that generative AI could be used as a way around actually hiring diverse actors. Rather than finding an actor who meets certain racial, gender, or ethnic parameters, a diverse-looking “synthetic performer” could really “just be a white guy at a computer.”

Blanco hopes that the protections in the SAG-AFTRA contract for AI are just the beginning and that as AI advances, the union will be able to seek stronger ones. But Bond and others fear that the technology will advance much faster than the next round of contract bargaining, which won’t begin until 2025.

As for what happens next, Bond hopes that the contract will not be approved in its current form and that SAG-AFTRA and the AMPTP will go back to the negotiating table to try to close some of the “loopholes” in the AI language. However, both she and Medína noted that they’d felt pressured to vote “yes.”

But it’s clear that this issue reaches far beyond the scope of SAG-AFTRA. Recently, President Joe Biden signed an executive order seeking to manage AI’s risks. In California, a bill is underway that would give actors the right to revoke consent when their likenesses are used. And, as Medína noted, there are organizations working toward anti-AI technology.

“I hope that people who are not in entertainment are paying attention to what the actors who are voting ‘no’ are saying because we could be the standard set for other industries if we get the proper protections,” Runa said. “And nobody is immune from this.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.