Rudolph the Red-Nosed Enigma

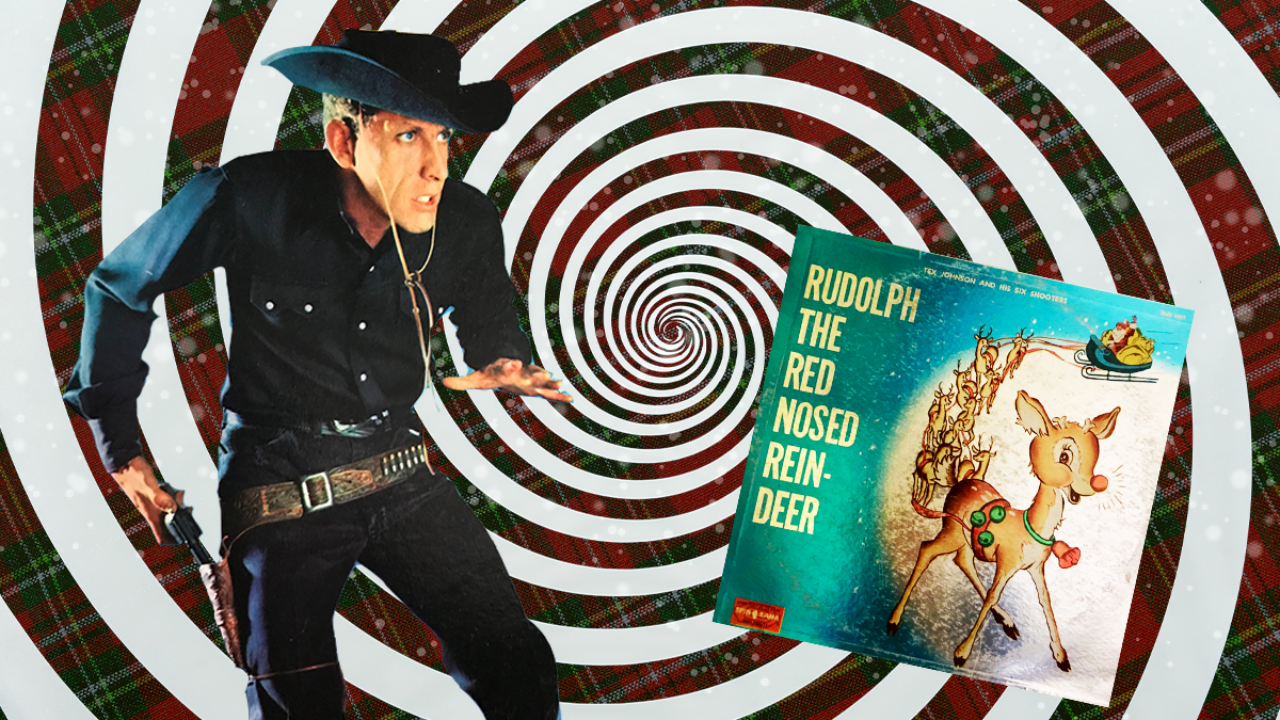

Where did Tex Johnson’s elusive Christmas album come from? Who recorded it? And why do so many people spend their lives searching for it? Will we ever know who Tex Johnson and His Six Shooters really were? (Graphic by Truthdig)

Will we ever know who Tex Johnson and His Six Shooters really were? (Graphic by Truthdig)

If you were to find yourself in a record store digging through a bin of Christmas albums, chances are good you would flip right past something called “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” by Tex Johnson and His Six-Shooters. The blue and silver foil cover features a cartoon of the famously freakish reindeer pulling Santa’s sleigh through a starry night sky over a snow-covered town. The track list of holiday standards would suggest it was just another child-friendly Christmas record, a generic, country-western gimmick. You’d keep going.

If, however, something led you to pick the record up, bring it home and slap it on the turntable, you’d quickly discover there was nothing generic about Tex Johnson’s “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.”

The album’s twangy country arrangements of “Rudolph,” “The Night Before Christmas” and other holiday favorites are accentuated by the head-scratching addition of concertina and electric organ. It’s hard to determine the identity of Tex Johnson, because a different vocalist appears on each track. The instrumentation varies wildly from song to song — including two a cappella numbers sung by an all-male chorus. While unmistakably a Christmas record, a quarter of the album’s 12 tracks, including “Cheyenne” and “San Antonio,” are cowboy ballads that have absolutely nothing to do with Christmas. A couple other songs mention Christmas only in passing, an afterthought amid the Old West trappings. What kind of fiendish producer would include the mournful “I Heard the Bells” and the downright grim “Just as the Sun Went Down” on a kid’s record? Yet overall the album is lively, catchy, goofy and makes no musical sense at all.

I first encountered the album in the mid-’60s, when my family was living on an Air Force base in North Dakota. One year as the season approached, my dad stopped at the base’s PX and bought the Tex Johnson record. No one can say for sure what dark whim led him to choose that one above all the others. It was the first of the many, much more baffling Tex-centric mysteries that would arise over the next 60 years.

“Rudolph” quickly became the one album my dad made a point of playing every December. Repeatedly. We had plenty of other Christmas albums around, but in our house, it was All Tex, All the Time. For years, my sister and I hated that cornball album, rolling our eyes every time my dad slid it out of the sleeve with a sly grin.

Overall the album is lively, catchy, goofy and makes no musical sense at all.

As the years passed, though, we started playing along with what had become an annual holiday joke. Maybe we just came to recognize how damnably strange the album was. There was an ineffable quality to it, a singular vibe that set it apart, but one I could never identify or describe. The joke grew into a family tradition. The day after Thanksgiving came to be known as “Tex Day,” when we marked the official start of the Christmas season by pulling out the Six-Shooters album.

When I was a kid, I assumed “Rudolph” was one of those ubiquitous Christmas albums found in every suburban household in America, like Bing Crosby or “Snoopy vs. the Red Baron.” I was mistaken. No one I knew had ever heard of the “Rudolph” album, let alone country sensation Tex Johnson. When I insisted on playing it for friends, I got blank stares and shrugs in response. To their ears it was nothing but the banal Christmas album promised by the packaging.

The first indication that something was more than a little off in the world of Tex came when I looked at the album’s back cover, hoping to find out who was responsible for this forgotten gem. Along with the track list, there were some technical notes about the specific recording equipment used, instructions for properly playing a stereophonic record and a biography of Johnny Marks, the songwriter who had penned “Rudolph.” But there were no credits of any kind. No musicians were listed, no producer or recording engineer, no record company, no studio and no copyright. There wasn’t even a label on the album itself to indicate sides A and B.

Okay, I rationalized, it was probably just a group of anonymous studio musicians fulfilling a contractual obligation. But no producer? No copyright? No record label, even? That was damned strange.

I left it at that, accepting it as a curiosity, a mysterious cultural artifact from a specific historical moment. But the album followed me, haunted me, and as an adult it remained the only Christmas album allowed in my apartment.

In 1995, I knocked out a little Christmas-themed story for a New York paper that included a brief mention of Tex Johnson and His Six-Shooters. The letters started arriving immediately. In the years that followed, they kept showing up every November and December. While not exactly a deluge, receiving two dozen notes from strangers about a quirky kid’s Christmas curio was hard to ignore.

The letters came in from all over the country — Colorado, New Jersey, Montana, Arizona — and they all said the same thing in almost the same way. It was a little eerie. The letter writers had all grown up listening to the Tex Johnson album thanks to a parent or grandparent. At first, they made fun of how awful it was, as I did, but in time it became a seasonal cornerstone, as it did for my family. As they grew older, they couldn’t shake it. Until they saw that passing mention in my story, they had always assumed they were the only one who had ever heard of it. Now, as adults they were desperately searching for a copy, both to re-experience it themselves and to inflict it on their own kids. They couldn’t say why they were so obsessed. They just were.

I was witnessing the emergence of the Cult of Tex. It wasn’t on a level with recalling the first time you heard the Beatles or Elvis or the Ramones. No, the Cult of Tex was a select group of people who had connected with the record at a specific time and under similar circumstances. For that tiny handful of people, Tex Johnson made such an indelible impression they were spending perhaps a little too much time as adults trying to recapture, well, something Tex represented. The question is what — and why.

I was witnessing the emergence of the Cult of Tex.

Determined to find some answers, I joined forces with another of Tex’s People, a retired teacher from Long Island, to undertake an investigation. The layers of obfuscation and misdirection we encountered were beyond anything I’d seen in my nearly 40 years as a journalist.

We soon discovered there were lots of Tex Johnsons out there, ranging from baseball players to Eric Clapton’s drummer, none of them country musicians. That was OK; we had guessed from the beginning “Tex Johnson and His Six-Shooters” was a collective pseudonym. Still, two other albums had been credited to Tex and the Six-Shooters: “Songs of the West,” a collection of kid-friendly cowboy songs, and “Gunfighter Ballads” (not to be confused with the seminal Marty Robbins album), a collection of classic C&W covers. All three were recorded by different and wholly unrelated ensembles and didn’t sound a thing alike.

To confuse matters further, the same “Rudolph” album had been released simultaneously (and with different cover art) credited to “Cactus Jim and the Wranglers” and “Slim Boyd and the Rangehands.”

The album, we discovered, had been released in either 1958, 1961 or 1967. It saw a single pressing and never came out on CD.

I found one reference claiming “Rudolph” had been released on Premiere, a Jersey-based indie label founded in 1958. It seemed a promising lead, as Premiere specialized in Christmas albums. They had indeed released an album called “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” but it was attributed to the Roy Scott Chorus. That was still a possibility, as Premiere was known for releasing albums under multiple names. Those hopes were dashed when I noted that not only was the track list completely different, the album itself was a lifeless Perry Como knockoff with nary a concertina, electric organ or cowboy song.

The cruel twists rolled on when I ordered a copy of the Tex Johnson original on eBay, only to find the Roy Scott record tucked in the familiar blue and silver foil sleeve.

While the obvious move in a story like this would be to include a link to the One True Tex album, it doesn’t exist online. It’s not available for streaming. There are no MP3s. If you do a search for “Tex Johnson and His Six-Shooters,” you’ll get plenty of results directing you to reliable sites, but all you’ll find are cheap imposters. The info on Discogs is spotty and inaccurate. Type “Tex Johnson” into Spotify and you’ll get Bob Wills. In one YouTube video, a DJ introduces the album in classic Cult of Tex-speak, then puts on that fucking Roy Scott album.

All the evidence indicates the album does not exist and never did. Did I dream Tex? It seems doubtful, as I’m listening to it now. That I was a character in an unpublished Philip K. Dick story was one possibility, but the emergence of the Cult of Tex leads to a more plausible conclusion.

Maybe they weren’t even pressed on Earth.

It may be that there’s no evidence of the album’s existence because so few were produced. Maybe they weren’t even pressed on Earth. Reading all the heartfelt notes from others felt a bit too much like “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” in which seemingly random people from all over the world had the same subconscious vision of Devil’s Tower. What if aliens had surreptitiously dropped two dozen copies of that singular album into a random smattering of stores around the country back in the early ’60s? And what if there was some subliminal message coded into the recording? Some kind of implant that crawled into the brains of anyone who heard that record one too many times as a kid? How was it all these people had nearly identical experiences, and were unable to shake the album later? Something that became such an obsession, all they knew was that they had to get their hands on a copy. Were we all sleeper agents with an undisclosed mission? Did the aliens want us all to get together and raise Universal Consciousness by playing “Wait for the Wagon” at a certain frequency?

I still don’t have an answer. But every year around this time I do wonder, and wait. Then I play the album again.

Your support is crucial...As we navigate an uncertain 2025, with a new administration questioning press freedoms, the risks are clear: our ability to report freely is under threat.

Your tax-deductible donation enables us to dig deeper, delivering fearless investigative reporting and analysis that exposes the reality beneath the headlines — without compromise.

Now is the time to take action. Stand with our courageous journalists. Donate today to protect a free press, uphold democracy and uncover the stories that need to be told.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.