Remembering First Amendment Icon Jim Larkin

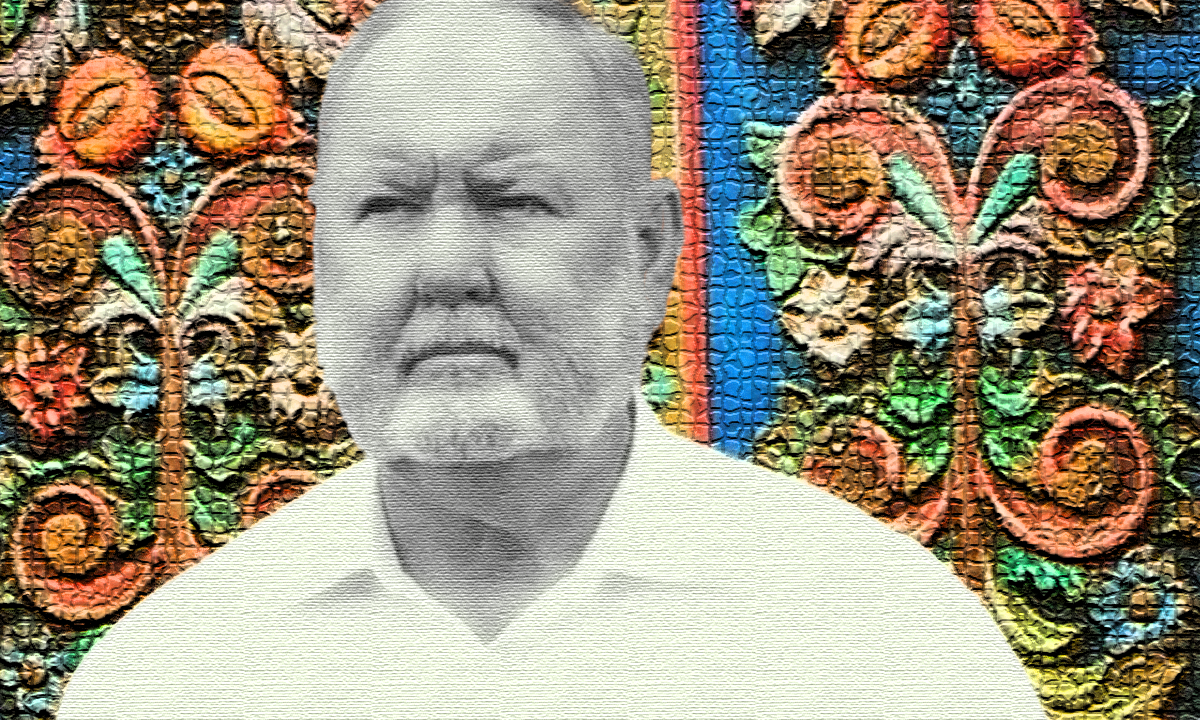

The fight for a free press has another martyr. Jim Larkin, 1949 — 2023. Photo: Wikipedia

Jim Larkin, 1949 — 2023. Photo: Wikipedia

Joan Meyer, the 98-year-old co-owner of a small-town newspaper in Kansas, died in the days following an unlawful Aug. 11 raid in which local cops stormed not only the offices of the Marion County Record, but her home as well. The nationwide outrage in response to such a draconian attack on the freedom of the press was immediate, deafening and wholly justified.

In contrast, Jim Larkin, the legendary and award-winning alt-weekly pioneer and fierce defender of the First Amendment, died on July 31, a week before his latest trial was set to begin. He was 74. To call the media response to Larkin’s death “muted” would be a stretch. The New York Times did not bother to run an obit.

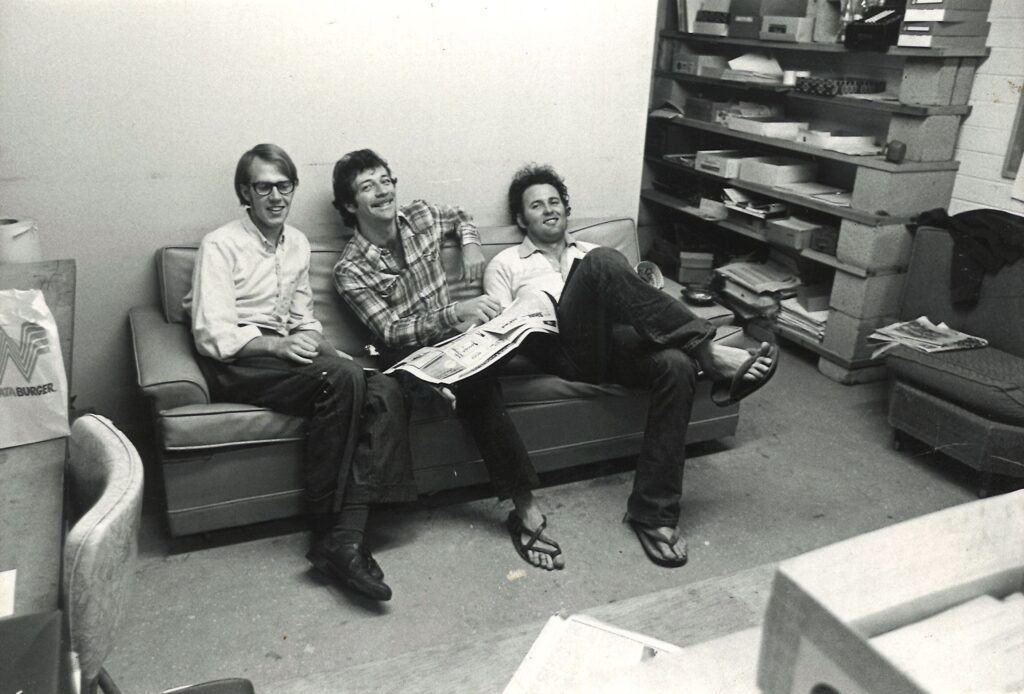

Energized by the Kent State massacre and the ongoing war in Vietnam, Phoenix-based Michael Lacey and a handful of Arizona State University classmates launched a counterculture newspaper they called the Arizona Times, in 1970. Two years later, Larkin, a fan of the paper who was working the night shift at a local diner, sent Lacey a handwritten note in which he mapped out the people, companies and agencies who really pulled the strings in Phoenix. Lacey invited him to join the paper and, thanks to his smarts and business acumen, Larkin was named publisher in 1974.

With Larkin as publisher and Lacey as editor-in-chief, the paper evolved into the Phoenix New Times, an alternative weekly that earned a reputation for its confrontational attitude, fearless investigative reporting and hip artwork. It inspired and became a model for other alternative weeklies cropping up in cities across the country.

To call the media response to Larkin’s death “muted” would be a stretch. The New York Times did not bother to run an obit.

Along with championing immigrant and abortion rights, civil liberties and free speech causes, Larkin and Lacey did not shrink from taking on powerful adversaries, including Sen. John McCain and Maricopa County’s notorious Sheriff Joe Arpaio. They often found themselves targeted for retaliation as a result. In 2007, years after a Phoenix New Times series exposed flagrant police misconduct and brutality in Maricopa County (as well as Arpaio’s crooked real estate dealings), Larkin and Lacey were arrested in the middle of the night on trumped up charges. The case went nowhere, and in 2013, Larkin and Lacey won a $3.75 million settlement in their false arrest suit against Arpaio. They distributed the money to local migrant rights nonprofits.

After four decades of fighting the good fight, Larkin and Lacey were considered patron saints of progressive media. All of that would change in a few short years, and by all appearances would soon be forgotten.

In the late 1980s, Larkin began acquiring papers from around the country (including the venerable Village Voice), creating a syndicate that boasted 17 alt-weeklies stretching from Miami to Los Angeles. Collectively, New Times papers would garner nearly 4,000 journalism and writing awards over the years, a Pulitzer among them.

Now, in business terms, one of Larkins most brilliant innovations at the Phoenix New Times — a practice eventually adopted by most alt-weeklies — was to reserve the back pages of each issue for adult-oriented classified ads for escort services, strip clubs and massage parlors. In alt-weekly circles, these were colloquially known as “hooker ads.” The justification for their inclusion was simple. Unlike many restaurants, bars and indie bookstores that bought ad space, the people who took out hooker ads always paid their bills in full and on time, usually in cash. Hooker ads were what kept most alt-weeklies afloat. In fact, many of Lacey and Larkin’s papers turned a profit, a feat almost unheard of in the newspaper business.

When the papers began launching online editions in the early 2000s, the adult classifieds were moved to a related but independent site called Backpage.com.

In 2012, Larkin and Lacey sold off the alt-weekly syndicate to a group of investors but maintained ownership of Backpage, hoping to build it into a classifieds outlet that could compete with Craigslist. They also launched a companion site, Front Page Confidential, which focused on investigative journalism and free speech advocacy. It was Backpage, however, that drew the most attention.

Gripped by a moral panic, politicians, lawyers and activists insisted that Larkin and Lacey were predatory digital pimps, not businessmen offering a platform for legally protected speech.

Backpage quickly became an extremely lucrative international clearinghouse for sex workers looking to advertise their services. As such, the site was carefully policed, and any ads that explicitly promoted illegal activities, like offering sex for money, were refused or deleted. In cases of suspected trafficking, the site coordinated efforts with law enforcement and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Government officials, however, assumed the site remained a safe haven for child sex traffickers. Gripped by a moral panic, politicians, lawyers and activists insisted that Larkin and Lacey were predatory digital pimps, not businessmen offering a platform for legally protected speech.

An extensive 2012 federal investigation into Backpage concluded otherwise. Federal prosecutors reported, “Even without a subpoena, in exigent circumstances such as a child rescue situation, Backpage will provide the maximum information and assistance permitted under the law…Backpage genuinely wanted to get child prostitution off of its site.” The government memo noted that witnesses have consistently testified to Backpage’s “substantial efforts to prevent criminal conduct on its site.”

That apparently wasn’t good enough for the site’s critics. Even after Larkin and Lacey sold Backpage in 2015, they found themselves targeted by state and federal officials. While prepping for a 2016 Senate run and hoping to build her political cred, then-California attorney general and future vice president Kamala Harris filed two suits against Backpage, accusing Larkin and Lacey of pimping. Both cases were thrown out by a judge who ruled that material on Backpage was protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, as well as the First Amendment. The ruling was not a surprise to Lacey and Larkin who knew their First Amendment rights from years of waging free speech battles.

Like the ACLU arguing in 1977 that Neo-Nazis had the right under the First Amendment to march in predominantly Jewish Skokie, Larkin and Lacey stood behind the too-often-forgotten chestnut that the right to free speech applies equally to those with whom you disagree. As they prepared for the next round of their legal fight, however, a shift was beginning to take place in the meaning and politics of the phrase “free speech.” As the world began grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic, “free speech,” once considered the most fundamental of American ideals, became associated in the media with “misinformation” and the spread of opinions deemed damaging to the public good and a threat to public safety. Before long, the term “free speech” was tarred with MAGA connotations, and those who advocated for it were seen as threats to democracy, not its rightful participants. Progressives who a decade earlier had considered Larkin and Lacey heroes now turned their backs on the pair. They were demonized as something even worse than critics of mask and vaccine mandates — they were pornographers who pimped out children.

Progressives who a decade earlier had considered Larkin and Lacey heroes now turned their backs on the pair.

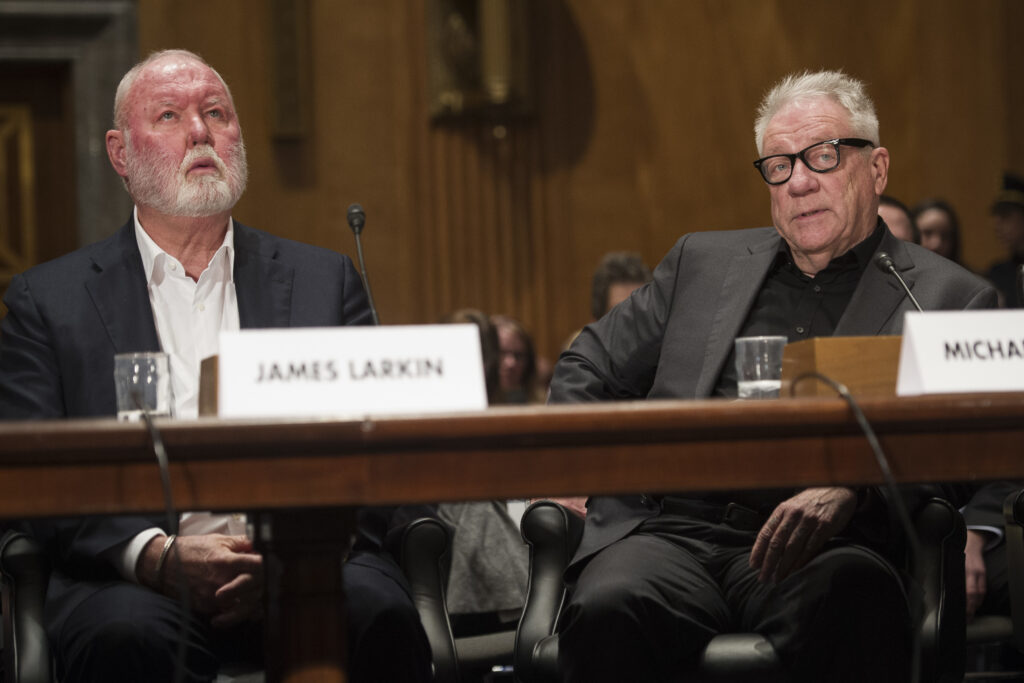

The next federal case was launched in 2018, a year after a judge tossed out Harris’ charges. In April, Larkin, Lacey and several other Backpage executives were taken into custody yet again and charged with 70 counts of facilitating prostitution, money laundering and conspiracy. To the dismay of thousands of sex workers who’d come to count on the website to make a living, the feds took control of Backpage, shut it down and froze the assets of the defendants. Not only did this prevent Larkin from supporting his family, it also meant the defendants couldn’t afford to hire their own attorneys, forcing them to rely on public defenders. A court filing describing Larkin as the operation’s “mastermind” ordered him to wear an ankle bracelet and be confined to house arrest until the trial.

“We’ve had people try to push us — politicians specifically — try to push us around all our lives,” Larkin told Reason magazine at the time. “When we come up to this battle, it’s informed by that history. All we’ve ever done is fight.”

When the proceedings got underway in September of 2021, Judge Susan Brnovich declared a mistrial after three days, upbraiding federal prosecutors for smearing the defendants by making repeated references to child sex trafficking (which was not among the charges) instead of focusing on the facts of the case.

A federal appeals court, however, rejected double jeopardy arguments and ruled the government could retry Larkin, Lacey and the others. The new trial was scheduled to begin in early August 2023.

In a pre-trial brief, federal prosecutors sought to bar any mention of free speech and the First Amendment in front of the jury, as well as any references to Larkin and Lacey’s history as award-winning journalists. They also motioned to seal the above-mentioned memos filed at the close of the 2012 hearing. While Judge Diane Humetewa upheld most of the prosecution’s requests, she agreed to allow limited references to the First Amendment during the trial.

“To me, the issue is, and always has been, the speech,” Larkin told Reason in a follow-up interview last March. “We platformed legal speech. The government didn’t like the speech, but it was legal. I know that we’re innocent and this has been a political prosecution from day one…If the government decides to point its finger at you, there’s really no question that they’re going to try to ruin you… Given the system and the way it’s set up, principled resistance could only go so far.”

He was right about that. Six years into this latest prosecution, the government finally broke him. Eight days before the new trial was set to begin, Larkin left his home in Paradise Valley, Arizona, and went to the Boyce Thompson Arboretum in nearby Superior, where he shot himself. After a half-century of fighting for the civil rights of those with little to no voice of their own — from sex workers to migrants imprisoned and tortured by Joe Arpaio — the few news outlets that bothered to note Larkin’s death couldn’t help but smear him. The USA Today headline read: “Backpage executive James Larkin dies before new prostitution trial.”

In deference to the death of one of the primary defendants, Judge Humetewa agreed to push the trial back three weeks. It began today, Aug. 29, sans Larkin, and is expected to run into November.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.