R.I.P No Labels, the Renegade Faction of the Centrist Elite

The group’s downfall is to be celebrated, but the deeper longings and forces it embodied will live on. People with the group No Labels hold signs during a rally on Capitol Hill in Washington, July 13, 2013. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

People with the group No Labels hold signs during a rally on Capitol Hill in Washington, July 13, 2013. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

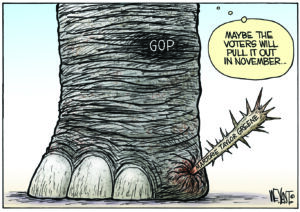

“Most Americans are decent, caring, reasonable, and patriotic people. But we do not see those traits reflected in our politics today. Instead, we see our two major political parties dominated by angry and extremist voices driven by ideology and identity politics rather than what’s best for our country.” Those reheated platitudes open Common Sense, a thirty-point quasi-platform issued last summer by No Labels, the shadowy group whose attempt to run a third-party presidential candidate in 2024 recently came to a close. They cast their failure to find a prospect in their usual terms. “We needed a leader of extraordinary bravery,” sighed No Labels’s CEO, Nancy Jacobson, in the Wall Street Journal. “Instead, we came face to face with the problems we were seeking to solve, including a system hostile to innovation and competition.”

For Democrats worried about a spoiler, the system’s hostility to innovation was welcome news. Erstwhile Republicans who cannot bring themselves to support Donald Trump—but would rather not vote for Joe Biden—no longer have an out. Without a No Labels candidate singing a siren song of bipartisan nostalgia soothing to upscale ears, they have to join Biden’s big tent. For the American elite (and for those curious about its propensities), the No Labels news marked a kind of changing of the guard. Early in the group’s history, a No Labels founder said to watch if politicians upheld the “three C’s: Do they reach across the aisle to co-sponsor legislation? Do they reach for common ground? Are they civil?” A decade and a half later, we’ve reached the end of the line for this handwringing banality, which defined a thousand speeches at rubber-chicken dinners across the George W. Bush and Obama years.

The disdainful bothsidesism promulgated by No Labels combined a lament against party polarization, a nostalgia for compromise however seamy, and a defense of neoliberal orthodoxy. No Labels bundled these three elements together as a collective project and promoted them with ever increasing petulance. In recent years, the calls for compromise came even louder than the underlying substance. As the threat of Trump and the tides of class depolarization drew most leading figures from the erstwhile center into the Democratic fold—and as new fissures pushed an influential segment rightwards to embrace what they deemed dangerous heresies—No Labels served as a throwback. By 2024, theirs was no longer the voice with the juice.

Without a No Labels candidate singing a siren song of bipartisan nostalgia soothing to upscale ears, they have to join Biden’s big tent.

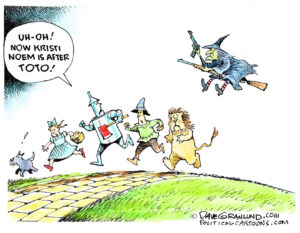

No Labels dates back to 2010. The group’s initial supporters drew heavily on the socially liberal, fiscally conservative financier types who would once have been moderate Republicans and pined for a Bloomberg presidency. They flocked to a group that waved the banner—bravely, per its self-description—for fiscal belt-tightening, with special emphasis on the dangers of Social Security. In the ensuing years, many of them have drifted away as distaste for Trump grew to dominate their political cosmos. Few big-name rich folks have arrived in their stead. No Labels enlisted various worthies in its efforts—sometimes splashy and public, sometimes behind closed doors to encourage candor and build relationships—aimed at encouraging dialogue and compromise. It flirted with a third-party challenge in 2012 and 2016 but stopped short. Under the leadership of Jacobson, supported by her husband Mark Penn—a longtime New Democratic pollster with a long list of enemies besides—No Labels ratcheted up its rhetoric. That the group resolutely refuses to release its donors leads to the obvious inference that it’s a right-wing plant designed to screw over Democrats. But that it chooses to do so via the subterfuge of nonpartisanship is a move worth its own investigation.

Now is an apposite moment to take seriously a group that desperately wanted to be taken seriously, and to make sense of just what they were as an ideological tendency and a political project. Yet as salutary (and, frankly, schadenfreude-filled) as the downfall of No Labels is, it would be a mistake to see it as the end for the deeper longings and forces the group has embodied. Whatever the form, the centrist elite will remain enamored of packaging their favored solutions as somehow above mere politics, and the rich and influential will continue to wring their hands about political entities to their left. There are few sure bets in politics—but this is one of them.

No Labels serves as the latest instantiation in the long tradition of anti-party politics. Parties, in that view, foment division that militates against the common good. The Framers had read and taken to heart the council of Henry Saint-John, Viscount Bolingbroke. In 1738, he had called for a Patriot King who would govern with public virtue and rise above party: “Instead of putting himself at the head of one party in order to govern his people, he will put himself at the head of his people in order to govern, or more properly to subdue, all parties.” John Adams read The Idea of a Patriot King five times. As parties began to form, initially as elite combinations more than mass organizations, the older line of thinking warned against dangerous combinations. Wrote the Virginian John Taylor in 1814, “By melting down the fetters of moral and republican principles in party confidence, we abolish the only known remedy against the evil qualities of human nature . . . and rest for security on ignorant mobs, guided by a few designing leaders, or on cunning combinations, guided by avarice and ambition.” The rise of mass parties sublimated this tradition. The Progressives gave it a new faith in ordinary citizens’ capacities, and the neoliberal era an infatuation with well-designed markets. But even if the classical virtue has gone—it’s hard to imagine anyone from No Labels quoting Bolingbroke on Meet the Press—the same fear of social conflict carries through.

For all its bluster, No Labels could never narrate its animating purposes beyond a vague notion of solutions and a desire that the “three C’s” serve as a yardstick for civic health. As Jamelle Bouie wrote in another evisceration of the No Labels delusion, “there’s no way to realize this long-running fantasy of politics without partisanship.” There exists no better account of that delusion than Common Sense, No Labels’s justification for its own project. Titled after Thomas Paine (an author there is no evidence No Labels actually read—“commonsense” is just a nice adjective to make its preferred positions seem, as another document from 1776 said, self-evident), the tract never identifies the major parties’ central failure, or what might replace those parties, or how a No Labels president without a political base would achieve anything meaningful.

The Common Sense version of our fallen present emerges from a blinkered past. The pat summary of American history offers a narrative with no agency, because that would mean winners and losers. “Slaves were emancipated. Women were given the right to vote.” A meandering path then leads to the notion that “all Americans can have the full measure of respect and equality they deserve, while giving parents a say in when and how their kids learn about sensitive issues of gender and sexuality.” To think, then, that “most Americans agree on foundational beliefs that many politicians have forgotten” perpetrates two lies at once: that most Americans agree, which they don’t, and that politicians’ forgetting means that they or their predecessors once remembered.

For all its bluster, No Labels could never narrate its animating purposes beyond a vague notion of solutions and a desire that the “three C’s” serve as a yardstick for civic health.

On the specifics, the commonsense majority appears when No Labels can string together a paired set of policies, but when public opinion disagrees, then the majority just approves of some anodyne principles that offer more or less nothing in actual guidance about how to solve tough problems. In those instances, however, when the No Labels ideas—around Social Security, for instance—are genuinely unpopular, then the respect for public opinion evaporates because, inevitably, we can no longer “kick the can down the road.” On the single issue roiling national politics where a straddle most means evasion, we get abdication with a pro-choice wink: “Abortion is too important and complicated an issue to say it’s common sense to pass a law—nationally or in the states—that draws a clear line at a certain stage of pregnancy.” Why now? No Labels makes no effort to explain why this particular moment demands this platform and these evasions.

The majority of Common Sense’s sixty-odd pages (there’s a lot of front and back matter to get to seventy-two) consists of small-bore solutions that feel decidedly retro—tort reform makes an appearance, as does mandatory national service. Idea 14 holds that “Financial literacy is essential for all Americans striving to get ahead.” The way to get there is a high school course, along with “limiting the inclusion of medical debt, and prohibiting the use of credit scores in many hiring decisions.” One wonders exactly what the “limiting” and the “many” would actually mean. If “No American should face discrimination at school or at work because of their political views” then the answer is robust unions to protect workers against management, but of course organized labor goes entirely unmentioned in the document. Instead we get a complaint about students being forced to self-censor in the classroom.

Above all No Labels, so prideful about treating Americans like adults, instead condescends to them. “America undoubtedly needs to spend more to protect our security,” we are told, “but we need to do so with much less waste and zero corruption” (emphasis original). That our political institutions make big change difficult, that public opinion is often fragmentary and contradictory, that politics is a battle of competing social interests over the distribution of resources and prestige, with winners and losers who then reshape the landscape—none of this is exactly a revelation, yet none of it seems to have occurred to the authors of Common Sense.

Somehow even more insulting than all this banality—and certainly more damning—is the cooptation of Thomas Paine himself. The arguments in the original Common Sense “were so clear and inspirational,” No Labels explains in an introduction to a document that is neither, “that historians rank Paine as one of the fathers of the American Revolution.” The group longs for a politics whose rhetoric will soothe. Instead, “we hear reason and persuasion—the pillars of our democracy since its founding—being replaced by anger and intimidation.” Paine, as any actual reader will soon discover, argued in a rather different tone: “To talk of friendship with those in whom our reason forbids us to have faith, and our affections wounded thro’ a thousand pores instruct us to detest, is madness and folly.”

The coruscating pamphleteer, the lifelong rabble-rouser, the instinctive internationalist—a figure so aware of how political ideas ought to circulate in their very purest form to every artisan and laborer, without euphemism or pretense—would have loathed all this pettifogging and obfuscation. Nothing exercised Paine more than vague appeals to past glories. To read him is to glimpse, more than from any other political thinker, the heady possibilities when a free people chart their own destiny. As he wrote in The Rights of Man:

The vanity and presumption of governing beyond the grave, is the most ridiculous and insolent of all tyrannies. Man has no property in man; neither has any generation a property in the generations which are to follow. . . . Every generation is, and must be, competent to all the purposes which its occasions require. It is the living, and not the dead, that are to be accommodated. When man ceases to be, his power and his wants cease with him; and having no longer any participation in the concerns of this world, he has no longer any authority in directing who shall be its governors, or how its government shall be organized, or how administered.

* * *

In its early days, No Labels represented a distinct investor bloc worried about the cost of ballooning deficits. By 2024, however, it had become defined ever more by the irritation of the politicians who mouthed its smarmy pieties. With the exodus of so many big donors, motivated (for good or ill) by policy as much as pique, the figures who have stuck around are those who want the limelight so much, and cling to their pox-on-both-your-houses story so desperately, that the price of Trump is worth it. See No Labels, then, as a renegade faction of what was once, in their salad days, the bipartisan tasseled-loafer class. What distinguishes the No Labelers from other moderates is their ongoing desperation for influence, their refusal to let the conversation move on, the persistent sense that working as a lobbyist, or telling war stories to old pals, doesn’t feed their hyperactive pheromones. Why else would the names Jon Huntsman, Ben Chavis (“Dr. King was a centrist. If he were alive today, he would be a member of the No Labels party.”), Joe Cunningham, Jay Nixon, and above all the late Joe Lieberman deserve any mention whatsoever? No Labels is the last way to maintain their grasp, and whatever the consequences for the country, so be it.

Of all the figures in the No Labels firmament, Lieberman now stands out as the defining spirit. While a student at Yale, he traveled to Mississippi for civil rights work. The young Bill Clinton played a part in his first electoral victory, to the Connecticut State Senate, as a “reform Democrat” in 1970. After he lost a race for the House in the inauspicious year of 1980, Lieberman remade himself into a mélange of the hawkish Scoop Jackson Democrat of the prior generation and the modern New Democrat, with a moralistic twist that to his detractors registered as smarm. He won election to the Senate in 1988 by running to the right of the patrician liberal Republican, Lowell Weicker, with an assist from William F. Buckley, whom he had known since his Yale days. In 2006, after his unrepentant support for the Iraq War, he lost the Democratic primary and, with the Republican standing aside, won his final term as nominee of the Connecticut for Lieberman Party. In retirement, No Labels became his defining cause—a way to stay relevant, to get back at the party that had spurned him, and to flatter his own sense of superiority all rolled together. He kept working the phones to find a presidential candidate until his death on March 29, following consequences from a fall.

The dominant faction of centrist elites recoiled at the No Labels of 2024. Comrades in arms, in their view, were taking up the wrong side for no good reason whatsoever. Many No Labelers and their current opponents once marched together as New Democrats. Al From founded their flagship group, the Democratic Leadership Council, in 1985 to battle organized labor and Jesse Jackson and take the Democrats to the center. New Democrats implored their party to abandon divisive, outdated commitments and embrace a results-oriented vision of the common good—exactly the formula No Labels would, with an anti-party twist, adopt decades later. As From summarized in 1991, “The old politics protected the organized interests. The new choice looks out for the interests of ordinary people. The old politics divided us by interest, constituency or class. The new choice unites us behind a common vision of what’s best for our country.” For their part, plenty of Never Trumpers now fully disenchanted with the GOP served together with their No Labels brethren under Reagan, Bush, and Bush, cutting taxes and waving the flag for American empire.

See No Labels, then, as a renegade faction of what was once, in their salad days, the bipartisan tasseled-loafer class.

Throughout the past year, with limited introspection about what got us here, centrists who want to stop No Labels, pro-Biden ex-DLC-ers and Never Trumpers alike, have sought to prick their friends’ consciences. Take a joint op-ed by From and Craig Fuller, the latter an aide to Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush before a string of jobs that sound like a parody of Republican influence-peddling: senior vice president at Philip Morris, CEO of the National Association of Chain Drug Stores, and so on. They minced no words. “To save the American republic, former president Donald Trump must be defeated. And that’s why the centrist political organization No Labels must cease and desist from its effort to nominate a third-party candidate.”

Credit where due to the No Labels whisperers: after decades excoriating liberals, they mounted a full volte face and, in turning their fire on their fellow centrists, lobbed the charge of betrayal. For that, they deserve real, no-snark credit. Nevertheless, they are not entirely persuasive when they claim to have stopped No Labels by making damned sure nobody would want to be its candidate. Indeed, No Labels itself more or less agreed with that diagnosis. “The trouble,” according to Jacobson, “was that no one was willing to take the hellish job we were offering.” The problem is deeper. For a candidate actually to appear on the ballot and do poorly would have vitiated the claim that the whining of an elite fraction could speak for a broad disaffected plurality or even majority. Though No Labels loved to trot out numbers saying two-thirds of Americans wanted an alternative to Trump and Biden, surveys with actual names showed their preferred candidate, Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, polling in the mid-high single digits.

Manchin, the great frenemy of the Biden years, decided instead to slink into retirement. Craving limelight and hoping not just to depart as a loser or a has-been, he wanted a final act. But all the tricks of trasformismo that powered his political career in West Virginia for more than four decades finally ran out of juice. And so, just enough the Democrat he has always been; not entirely sold on a version of moderation so powerfully tied in with the ideology and mores of the global elite; and, above all, politically shrewd enough not to go down with the ship, he demurred. Lieberman, the true believer in the No Labels project, called through his Rolodex until his fateful fall. Manchin, the cannier politician, awaits the future he didn’t really want but prefers to the alternatives. In the meantime he can bemoan the perils of our tribal politics on the speaking circuit.

* * *

And yet, and yet. Just as the No Labels candidacy shuffled off with a whimper, deeper perils reemerge. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., another survivor from the political detritus of the 20th century, now polls in the double digits, better than a No Labels alternative ever did. Third-party candidates typically fade down the stretch, and ballot access remains an issue for his slapdash campaign. It is reasonable to assume that an erstwhile Democrat with a famous name will hoover up votes from a mélange of subgroups who have, for this reason or that, found reason to dislike the Democratic Party, its feckless nominee, and the smug educational and cultural elite that it represents. However, if the dynamics work just so, an anti-vax anti-establishment alternative could well cut into the Trump coalition to an even greater extent. Beyond an anti-establishment cred greater than that of No Labels—not because of biography but because he now embraces loopy views—RFK Jr. has no more systematic an account than they did of exactly what defining issues will cleave the electorate and win him his majority. As an immediate electoral matter, he looms large, as do Jill Stein and Cornel West. As a figure of history, however, RFK Jr. stands at the awkward interregnum.

An influential subset of American capital once broadly on board with Obama-era technocracy—more so than the financiers of early No Labels—has swung hard right.

That rough beast is more in tune with where the real money now lies. An influential subset of American capital once broadly on board with Obama-era technocracy—more so than the financiers of early No Labels—has swung hard right. Puck’s Teddy Schleifer, who follows their doings, tweeted recently that “Based on my private conversations, the amount [sic] of major business leaders and billionaires who will support and/or donate to RFK Jr. will shock you.” George Wallace in 1968 (to take the year for which political analogies are in fashion) was the way station for many of his voters as they journeyed from the Jim Crow–era Democrats to the Republicans. For today’s billionaires, RFK Jr. seems set to play that same role.

These divides suggest how the new cleavages emerge from the old—and the perils for Biden of ongoing intra-coalitional battles this year. Cockroach-like, No Labels will not give up. Leaving the “three C’s” behind and seeing a place where its elite supporters can come together and punch left, the group recently brought together 300 supporters, including some university trustees, for “a special Zoom call” with two of its most reliable friends in the House of Representatives—Josh Gottheimer of New Jersey, a Democrat, and Mike Lawler of New York, a Republican. The attendees encouraged the FBI to go after student protesters, and the members promised further investigations. The chair of the board of Washington University in St. Louis—a private equity exec, bipartisan political giver, and No Labels board member—explained that campuses had descended into “chaos and anarchy.”

And so, even as one peril passes, another still looms, and the dangers grow after that. At a moment when divides seem so stark, best to ponder some other lines, without easy allegory, from the original Common Sense:

Your support matters…O! ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only the tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the Globe. Asia and Africa have long expelled her. Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.