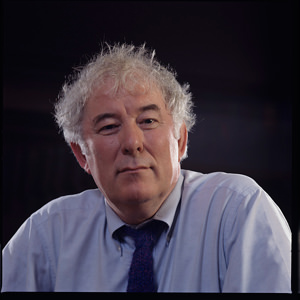

Poet and Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney Dies at 74

No anthology of Irish poetry (or, arguably, contemporary poetry) is complete without an entry penned by Seamus Heaney. Friday, the literary world lost a treasure when the renowned bard died in Dublin, after being hospitalized due to a fall.

No anthology of Irish poetry (or, arguably, contemporary poetry) is complete without an entry penned by Seamus Heaney. Friday, the contemporary literary world lost a treasure when the renowned bard died in Dublin, after being hospitalized due to a fall.

It’s been said that Heaney was the greatest Irish poet since W.B. Yeats. In an interview Friday, Paul Muldoon, a compatriot and poetry editor of The New Yorker, explained what set the two poets apart. Muldoon said that although Yeats was well known, he did not posses the “ability to touch the people in the way that Seamus did.” Heaney, he goes on, was so profoundly devoted to Ireland that he nearly became “indistinguishable from the country.”

A Catholic nationalist born in Northern Ireland, he moved to the Republic of Ireland to spend his days there. The BBC notes in its obituary that during the troubles in Northern Ireland, Heaney came under fire for seeming outwardly ambivalent toward attacks by republicans. He refused to become a “spokesman,” despite the pressure to do so, choosing to write elegies to those who became casualties of the violence rather than outright expositions of his political views.

And yet, though never a spokesman per say, his poetry exposed the universal, ancient violence still prevalent today. Poet and critic Dan Chiasson writes in his “Postscript” for The New Yorker:

Heaney’s poems were full of finds, unlikely retrievals from the slime of the ground or the murk of history and memory. His poems about peat bogs and what they preserve are probably the most important English-language poems written in the past fifty years about violence—the “intimate, tribal revenge” that underscores the news. But they never stray an inch from the personal tone that Heaney honed in his poems about his four-year-old brother’s death or his mother’s method of slicing potatoes into soup. That the same vocabulary, the same notes, and the same intelligence could govern his personal poems and his political ones only pointed to the arbitrariness of the distinction.

There is no denying Seamus Heaney’s poems made an indelible mark on literature. Translator, teacher, radio broadcaster—he wore many hats, the obituaries remind us, but to those who had the good fortune to know him, he was also a magnanimous human being. Chiasson says of him, “Heaney’s poems made you feel confided in, addressed at close range; he was like that in person, too.” Robert Pinsky, three-time poet laureate of the U.S., expresses gratitude in Slate for the poet he knew personally, explaining that while reading about the lives of other writers he’s found many can be “mean or petty or worse” despite their greatness. Heaney, however, was as kind as he was talented; Pinsky recalls, “His understanding of other people, individually and in groups and in nations, made him a master of occasions and a supreme teller of jokes and stories. The same quality makes him a great poet. Thank god for him. …”

In a poem that is sometimes deemed his manifesto, Heaney compared his work as a writer to his grandfather digging turf and his father digging potatoes. The poem, titled “Digging,” ends:

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

Dig he did—into history, into truths, into hearts—and now that he’s gone, he’s left a tremendous hole but also a path and squat pen for others to use.

—Posted by Natasha Hakimi

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.