PBS Anchor Judy Woodruff Warns That the Recent Attacks on the Press Subvert Democracy

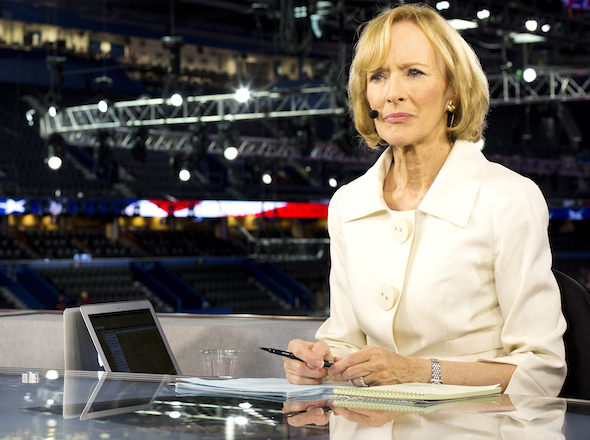

Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer sits down with the co-anchor and managing editor of "PBS NewsHour" to discuss the future of journalism and the need for a more diverse media. Transcript added. Judy Woodruff on the set of "PBS NewsHour." ("PBS NewsHour" / CC 2.0)

Judy Woodruff on the set of "PBS NewsHour." ("PBS NewsHour" / CC 2.0)

This week’s episode of “Scheer Intelligence,” a weekly radio show hosted by Truthdig Editor in Chief Robert Scheer, explores the changing landscape of journalism. Scheer sits down with journalist Judy Woodruff, co-anchor and managing editor of PBS NewsHour, to delve into her past and discuss her vision of the press of the future.

Listen to the full interview below:

—Posted by Emma Niles

Transcript:

Robert Scheer: Hello, this is another edition of Scheer Intelligence, done for KCRW. And the intelligence comes from my guests; in this case, it’s Judy Woodruff, the legendary journalist. You know here from, originally, NBC and then CNN, and then mostly, I think, from PBS, where she still is holding forth. Not only holding forth, but sort of starring. And I met Judy back during the Jimmy Carter campaign in 1976. And I want to begin there, Judy. Because the issue I had then–and I was one of these snobs from New York, and I really didn’t know the South. And I’d been through Plains and that part of Georgia in 1960. And we fast-forward to ’76–I wondered how much had changed. And I remember writing at that time in one of the profiles I did, oh, this new South is just the old South plus air conditioning, you know. Now, you were born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, but you basically got your education, high school in Augusta; you knew Georgia well, you graduated from Duke, you went to work for a local station. And so was that just a smart-alecky thing that I was writing, and did the South change? And if it changed so much, as Jimmy Carter had expected, why did this election turn out the way it did, with a very sharp, racially divided vote in the South?

Judy Woodruff: Well, first of all, Bob, it’s great to talk to you. And I’m just so glad you started out by acknowledging that you were a snob back in 1976 [laughter]. I think that’s a wonderful piece of humility on your part. Do you want to elaborate on that before we talk any more?

Scheer: Well, I thought the South was a place of hicks and racists [laughter]. And, you know, and as I say, I’d been through there in ’60, and it was not a pleasant experience. And I participated–you know, there was Koinonia Farm was up the road from the Carters, and that was one of the rare places where they had actually tried integration, basically on a Christian basis; the Bible seemed to call for it, and they were, you know, bombed and shot up and everything. And some people in the Carter family helped them; Lillian, his mother, and Billy; but not others. And in fact, as long as we’re going back to that period, I remember leaving Plains during that election, and Hugh Carter, Uncle Hugh, had a store. And I remember going into that store with Jody Powell, and suddenly, with the media gone, Hugh Carter was being an old-fashioned, redneck racist. And Jody, who was Jimmy’s press secretary, was quite embarrassed. And I suddenly realized, wait a minute, maybe this whole thing is a movie set, and maybe I’m not being arrogant here. And as I say, if we bring it up to the present, where is the new South? It seems to be sharply divided along racial terms. Am I missing something?

Woodruff: Well, I think–you know, I just want to say that when I moved to Georgia I was, what, 12 or 13 years old; I had lived, had grown up as an Army brat, lived all over the world. And when I learned that my father had been assigned to Fort Gordon, Georgia, I immediately had a mental picture of cotton plantations, people going around barefooted, and I didn’t know what we were landing in. And I, even as a young teenager, was skeptical about moving to the South. And I came to understand, in the six years that I lived in Augusta, that the South is a multilayered place and that one blanket description doesn’t do justice to the South, just as it doesn’t do justice to any other part of the country. So, sure, there has been racism in the South, and sure, there have been some really terrible things done in the name of race and religion and ethnic prejudice; there’ve also been some good things that have come out of the South, just as they have every place else. So I’m going to start out by saying, I think it’s wrong to paint the South with a broad brush. Because there are exceptions to just about every rule. But your question, Bob, is has the South changed; I think the South had evolved by the time I moved there in the early 1960s, and it’s evolved even further. It’s today not the South that it was then; there’s a different economic base, the education picture is different. Having said that, the South still votes overwhelmingly conservative compared to much of the rest of the country–maybe not so conservative compared to the upper Midwest, if you look at what happened in this presidential election last year. But it has changed. And at the same time, Bob, you know very well that the political activism in the South has changed before our very eyes. And a lot of that, I think, has to do with who’s living there: you’ve got a lot of transplants from the North, who bring very different sensibilities; you’ve got communities, particularly communities of higher education, across the South, with people who have, I think, very different ideas from others who live in the South. You also have growing minority communities in states like South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and so on, and they are making their voices heard. So it’s a much more complex and, I think, nuanced picture than people often paint. But you’re right–if you just look at who some of these states send to Washington, who are their senators, who are their members of Congress, who do they send to the House of Representatives–you know, it’s easy to, I think, to get a picture, but not entirely the accurate picture.

Scheer: Let me ask you about an area that I know you are very expert on, and that’s the role of women, and particularly in journalism. And you’re one of the founders of a really significant group called the International Women’s Media Foundation, which has done an awful lot for women around the world; you’ve devoted a lot of energy to it. And I just want to ask you a personal question about your own trajectory, because I remember you were, when you started, you were working with the Today Show and you were covering Jimmy Carter. And I remember you did some very important, investigative pieces. And I don’t want to put words in anyone’s mouth, but I gather the response from New York was more about your appearance than the substance of your investigative report [laughter].

Woodruff: Oh my gosh. Wait a minute, you’re not telling me there’s a double standard for women, are you?

Scheer: Well, I just remember you being very ticked off–that it had something to do with, did you do your hair that morning, rather than, you know, you had spent weeks investigating a story of great substance. So you are a pioneer in this business, and there’s a tendency to think oh, well, those problems are solved. But you know, the whole reason you devoted energy to the International Women’s Media Foundation, certainly internationally, women suffer a lot when they function as journalists. And you award Courage Awards towards that. But the situation in the United States also remains a very serious one, no?

Woodruff: Well, it does. I mean, we’ve made incredible progress, because sure, there are so many more women now as reporters, and more women editors, women producers; I mean, our executive producer at the PBS NewsHour is a woman, an amazing journalist, Sarah Just. Our former executive producer was another amazing woman journalist, Linda Winslow. So we have a history of prominent women, and of course the extraordinary late Gwen Ifill, who was my co-anchor and close, close friend, who passed away last November. I mean, I’ve been so fortunate to work with some of the most, just extraordinary women journalists anywhere. But the point you’re getting at, Bob, is that the standards for women are different, and yes we’ve made progress, but we still have a long way to go. And I can’t disagree with that. I mean, I’m so thrilled when I pick up the newspaper and I see female bylines, much more than I used to. And I know, certainly when you turn on the television and you watch television news, you see more women reporters covering just about everything from war–and by the way, I’ve decided more of our correspondents covering our war zones are women than men. At least, it seems that way to me; that may not be completely accurate. But we still don’t have enough women in positions of leadership: women doing the hiring, women deciding on story coverage, women, frankly, you know, calling the shots. And that’s what we need more of: we need more women newspaper editors, executive producers, such as the one we have at the NewsHour. And why do we need it? Because we in the media need to reflect the whole country; more than half the country is women. It’s not that women are going to cover the news so differently, it’s just that we, I think, bring a perspective and a history and a sensibility and, frankly, a set of life experiences that’s different. And that ought to be respected and reflected.Scheer: And I know you need to cover this administration, and so I don’t want to, you know, make that any more complicated than it is. But we did have these big marches recently of women who are concerned about what happened in this election. And it does seem, hopefully that fear is misplaced, but it does seem that somehow, the more things change, the more they remain the same as far as the role of women. But I guess it’s too early to actually reflect on that.

Woodruff: Well, I was struck that the final vote–because going into this election we, I think a lot of us in the journalist community thought that Hillary Clinton was going to win a bigger margin of the women’s vote than she ultimately did. She did win the women’s vote, as you know, but a lot of that was carried by minority women. She–white women, she had a much tougher time with white women; Donald Trump did better with white women, I think, than a lot of people expected. And we know, we all know the outcome. I think like men–and I don’t mean to drop the subject of women; I’m glad to talk about it–I think a lot of people in this election ended up taking the result for granted. I think they thought they knew what was going to happen, and they didn’t think it was important to pay attention, or important to turn out and vote. And I think that explains, you know, the outcome in a number of states around the country. I think people, many people who are now marching in the street and holding protests–I mean, just today there’s a protest as the new Secretary of Education went to, she went to visit a public school in Washington, D.C. and there were 50 or 60 protesters standing outside blocking her entrance. There are protests–I’m calling it the democratic street coming alive. You could ask, where were these folks on election day? And I think that’s a legitimate question to ask. But I do think that there’s a big, big chunk of this country, including a lot of women, who did not get engaged in the election. And they’re seeing now that their votes count, and they need to be engaged going forward.

Scheer: Yeah, but let me ask you about class and women. Because the AP had a very good story this week up in Wisconsin, who voted for Trump and why did women vote for Trump, working-class women and so forth. And they had a scene where a woman climbs up on a chair and gets a box and says, OK, here, look at these nine envelopes; these are the bills I have to pay every month, and every month I have to decide which three or four I can pay, whether it’s the house payment or even something for the vacuum cleaner that we bought on payments, or the car payment, or sending the kids to their music lessons or something. And isn’t there a problem with both the Hillary campaign, the Hillary Clinton campaign, and with the women’s movement, that it did not pay enough attention to the needs of working-class women who are struggling? In this case, a woman making ten, twelve bucks an hour and trying to survive, and having two jobs, and her husband having two jobs? I mean, wasn’t there something skewed about a female candidate that would give speeches to Goldman Sachs for almost a million bucks?

Woodruff: Look, even people who worked very hard inside the Hillary Clinton campaign acknowledge today that they did not do enough to reach out to working people in this country, that the message was not there, or at least it wasn’t expressed in a way that connected with people, that there wasn’t a sense that Hillary Clinton got their concerns and got and understood what their lives are like. And you know, look, the caricature is Hillary Clinton had a seven-point plan or an eight-point plan for everything, and that the campaign had thought through the policy implications; but what didn’t happen–and again, this is coming from Democrats and people who work for her–is that the connection didn’t, people didn’t feel the connection. Somebody told me long ago the vote you cast for president is the most personal vote you will ever cast, because you’re thinking about, this is the person I’m going to be looking at on my TV screen; I’m going to be reading about them every day; and today we know we’re going to be looking at them on our mobile device, whatever it is, a thousand times a day, from the time we wake up in the morning and go to bed at night. So it’s got to be somebody we want to see and want to hear from. And for a whole set of reasons, Hillary Clinton didn’t make that sale, including among the people you talk about–the very people who, you could argue, have the most to lose and the most to gain from this election. So there’s plenty of blame and credit to go around for this election; I don’t think it all falls on the shoulders of Hillary Clinton, but surely some of it does, just as any election will.

Scheer: The whole reason for these podcasts is I’m trying to search for these American originals, you know; how this crazy-quilt of American culture throws up really interesting people, whether it’s Ralph Nader, or–you know, I have a whole long list. I just did Willie Nelson, a two-part, and so forth. And the reason I wanted to have an interview with you is I was always impressed with you as a journalist–that despite the fact that you are very successful, have become very famous and so forth, you never lost the common touch. And I’m not saying you’re the only one that retained that, but I always thought that was really the secret of your value. And I remember when we were covering Carter back then, but over the years, you’ve always sort of been tuned into “Yeah, but what is the person working in the luncheonette thinking?” Or “What is that other person working in the assembly line thinking?” And isn’t there really a danger as to what happened to our journalism, and why populism, whether in the case of Sanders or Trump, became so important–it’s that the elite of these two parties lost that touch. They didn’t really know that for forty years, life had not been improving for a lot of people. Because it had been improving for journalists, many of them, or for political people.

Woodruff: You’ve hit on, I think, a point that we all need to think about really hard. I agree that there’s evidence that both political parties lost touch with hard-working Americans. And there’s no question, because journalism is based in Washington, D.C., where I am right now, or at least I’m in our studio in Virginia right across the Potomac River. Because we’re in Washington, which is a bubble, or in New York, which is another bubble. Some of us are on the West Coast, where you are, but most of us tend to be in our bubbles. And we try to get out, and we try to talk to people as much as we can, and that’s a huge priority for us on the NewsHour, to get out in the country. But it’s hard sometimes, and it also costs money; and I’m not saying that as a complaint, but to get out, to travel, to talk to people, we have to make an investment in doing that, and we can’t stop doing it; we have to do more of it. I don’t think we did enough of that last year. We did some of it; we sent some of our best reporters out around the country. I was able to get out a little bit. But I think you never can do enough of it. You don’t understand an election unless you get out and you talk to real people, and you know what’s going on in their lives and in their hearts. And I think that’s a big part of the reason the press missed this election.Scheer: So let me ask you about the state of the media. Because right now there’s a lot of hand-wringing, a lot of talk about fake news and the denunciation of cable and everything else. And I wonder whether we’re glorifying the good old days. And I just, for example, to take it back to the South, this is a country that had segregation for a very long time, and basically ignored it, even when it extended into our major sports activities and so forth. And not just baseball, but when the Lakers came to L.A. over fifty years ago, in the NBA there was a thing, only two Negro or black players could be on a team; more than that was too much, and so forth. And so even in the glory days of journalism, wouldn’t you agree there was also a lot of fake news, or ignoring important news? Or are you of the school that it’s all gone to hell in a handbasket?

Woodruff: No, I think we’ve always–you know, look, we’ve always had our mistakes and our gaps in what we do. We get pretty full of ourselves too much of the time, and we think we’ve got most of the answers. I think to be a good journalist, you have to stay humble; you have to remember every single morning when you wake up, you don’t have all the answers, you don’t know everything, you haven’t gotten it figured out. And you need to keep asking questions and just increasing your understanding, but don’t ever, ever, ever assume that you’ve got it figured out and that you know and you don’t need to talk to anybody anymore, and you don’t need to report and you don’t need to keep digging. It’s endless. No, but what I think right now, Bob, is that we are–we are in a kind of a new place, though, because of what’s happened with the internet and social media. There’s just so many more sources of news, and people are picking and choosing where they get their news, and they’re rejecting news that doesn’t look like what they already believe. And I think that makes it harder for us, and it makes it harder when more and more politicians are calling us liars and dishonest. But I don’t think we get–I don’t think, you know, we fold up and fold our tents and disappear; what we do is we get up every morning and we, you know, we [laughs] put our shoes on and, what is it, somebody said you put your pants on one leg at a time, and just keep going. And ask the hard questions, hold others accountable who are in public office, take a deep breath, don’t get carried away with either yourself or with a story that you think is too big or too crazy; don’t get carried away, just take it one at a time. We have to do that; we owe it to the American people, and I–I mean, you, I don’t know if you want to hear my whole spiel, but I absolutely believe our democracy depends on a free press and on a press that’s prepared to stand up and hold, again, hold our leaders accountable. They have to be held accountable; we can’t, you know, this is not a government of press releases. And no matter how much we are insulted or criticized, or whatever, we have to do our jobs. And that doesn’t mean we don’t make mistakes; we make lots of mistakes, but when we do, we acknowledge it.

Scheer: You know, but the reason I’m pushing this–and we’ll take a, we have a few more minutes, if you’ve got the time–but I just, I think it’s a really important thing. I happen to teach at the University of Southern California in the Communications school, and I try to tell our students, these are the, in many ways, the best of times to be a journalist. Maybe not to make a living [laughter], but then again, you know, for print journalists in the old days before you TV people came in, it wasn’t such a great living. You know, we were called ink-stained wretches, and you know, it wasn’t such a, we weren’t supposed to be really up there. Then the salaries got inflated because television brought in a lot of big bucks, which was good. But if what you really want to do is read a diverse source of information, have access, and even publish and do your video, people now can make TV; they can make movies; they can report. And I just was thinking of the good old days; a hero I had, and I don’t know if he’s still your hero, Tom Johnson, who actually had a lot to do with your being, right, at CNN, and also–

Woodruff: Absolutely. I stay in touch with Tom, he’s a wonderful guy.

Scheer: Yeah, and he’s one of the guys I really respected; he was the publisher of the LA Times when I was there, and he’s from Macon, Georgia, actually went back to his hometown to try to figure something out about his own life, and he grew up fairly poor, and before he got involved with Lyndon Johnson. Bill Moyers is another one I respected very much, and had a real, to this day has his fingers on the pulse. And yet, when I was working at the LA Times twenty years after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which was the reason we got into the, expanded the Vietnam War, Lyndon Johnson claiming there was an attack on American ships–the secret documents were revealed twenty years after, and it turned out it was a total phony; the second attack had never occurred. And I had to go downstairs to Tom Johnson and say to my publisher [laughs]–ask him, did you know? “No.” And the same thing, Bill Moyers was then, I think, the press secretary for Lyndon Johnson; they were, I guess, in the dark about it. And so in terms of “fake news,” as I tell my students, there’s all this hysteria–we’ve always had fake news. After all, you know, the effort of the FBI to smear Martin Luther King and destroy him, right? You know the whole history.

Woodruff: Well, every government–yeah, I mean, every government, no matter who’s in power, they want to look as good as they possibly can; they want to cover up the bad stuff. It’s just, it’s human nature, it’s what happens. And that’s why we need the press. And I mean, it’s not so much–I mean, to me that wasn’t fake news; that was an administration covering up, you know, bad stuff. And that’s always going to be that way.

Scheer: No, it was fake news in the sense that in real time, they knew in the White House, Lyndon Johnson did anyway, McNamara did, that there hadn’t been, there was no reason to believe an attack had occurred. And actually, it came up for me because I was on the MacNeil/Lehrer show with McNamara at one point, and had the effrontery to suggest he had lied about it. And you know, people were offended, that was a stylistic thing, you know; you went too far, Bob. But the fact of the matter is, that was fake news, you know? And the weapons of mass destruction which the New York Times supported in Iraq was fake news. It was, you know, Breitbart did not invent fake news; we’ve had fake news before. And now, at least what I tell my students, you can get on the Internet, and as long as it’s fairly open and net neutrality and so forth, you can read what is being said in media around the world, right?

Woodruff: Absolutely. I mean, I agree with you; I think this is a perfect time to jump into journalism, as long as you don’t [laughs] care about–you know, you don’t go into journalism to become wealthy; I mean, that’s just not what we do. You go into journalism because you love reporting and you love digging, and that’s something, if you get bitten by that bug I don’t think it ever leaves you. I mean, I don’t know anybody who ever, who was in love with reporting and with journalism who just stopped being curious and stopped. But I mean, you make a very good point; there are always going to be stories out there; I mean, you can go back to the beginning of time. You know, people have reasons; they don’t want the facts out, they don’t want people to know what’s going on. And I just look at it as another reason why we need young people to go into journalism, to set us straight. You know, to keep digging, keep asking questions, go into the basement; you know, go through those old files, go through those old documents. You know, keep asking questions, keep making FOIA, freedom of information requests. And I think there’s something going on today. I find more and more young people interested. I guess I thought a couple of years ago that young people were turning away from journalism because they were watching the fact that so many newspapers were laying reporters off, and even television news organizations were laying people off. But you know, we’re seeing a kind of a renewal, a resurgence, I think, with online and social media. And there are a lot of places and ways to report and dig; the kind of things, you know, what Truthdig does. I mean, you know about that; there’s just so much going on that we did not have a vehicle for back in the day. And there’s a, you know, there’s a need for these young people to come in. So come on in the water’s fine [laughs]. Scheer: I think this thing about the bug–getting the bug–is really the message. And as I say, the reason I wanted to talk to you as an American original, because I really do have such enormous respect for how you’ve conducted your life as a journalist, as well as your husband Al Hunt, who I think is also a legendary journalist. So there are a lot of good role models out there. But the bug is the important thing. And unfortunately, very often in these schools and everywhere else, we seem to be teaching that careerism trumps everything. And so somebody looks at you and they say, oh, Judy Woodruff; easy for her to talk, she’s famous, she makes a good living, et cetera, et cetera. But I know enough about you to know that you risked your career. You–because of the bug, because of your commitment–you didn’t go along all the time. And I don’t think that’s a message we send out to people enough about this [journalism], precisely because it’s so important to the functioning of a democracy. That you have to take risks. And also, maybe it’s a big mistake to think of journalism as a high-paying career. Maybe it’s something you do because of passion and some sense of writing the wrongs of this world. I don’t know.

Woodruff: Well, without accepting all those very nice things you just said, and I appreciate it, I have to say, I think if you don’t have that bug, if you don’t believe that you can make a difference as a reporter, and if you’re not driven by this idea that we, that our democracy depends on an unfettered, free press–and that means the ability to ask tough, uncomfortable questions and get access to information that people want kept, you know, hidden–then, you know, if you don’t have that, then think about doing something else. But I think there are enough, I do–I meet young people almost every day who come up to me and say, I’m thinking about journalism, should I do this? And I say, look, if you really love this, if you are curious, if you don’t like the answers you’re getting, if you always have the next question, journalism is something you have to think seriously about. And I really believe it; I think the future of our country depends on it. I don’t know how many Americans realize that; I think a lot of people look at journalists and probably think we’re a bunch of jerks who, you know, too big for our britches. And that’s unfortunate, but I think, you know, we didn’t–you don’t go into this to be popular, and you don’t go into it to be liked. You go into it to serve and to, again, to hold–I’m a broken record, but to hold people accountable who are asking the public to give them their trust. And they have to be held accountable.

Scheer: Thank you, Judy Woodruff. Thank you, Joshua Scheer and Rebecca Mooney for producing this. And Kat Yore and Mario Diaz with the special leadership role of JC Swiatek today for this recording. See you next week.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.