Part II: It Will Take a Political Movement to Reform a Politicized Supreme Court

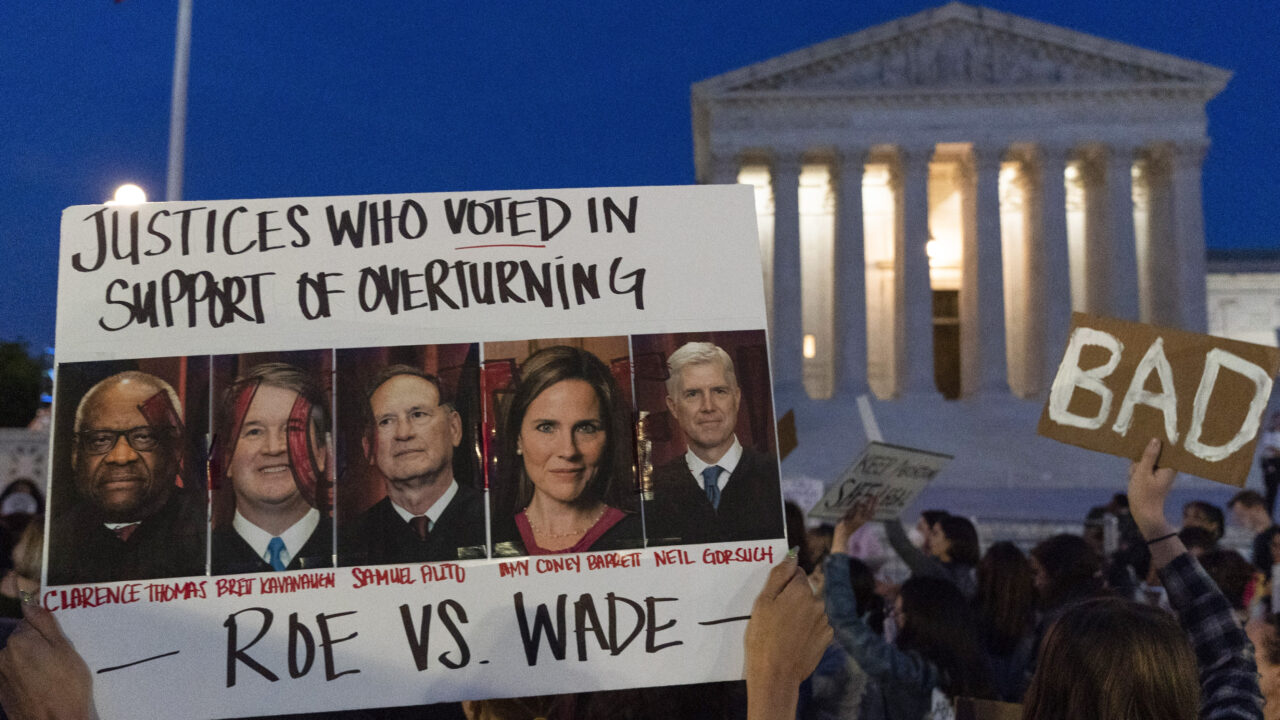

It is time to revive Franklin Roosevelt’s court-expansion plan in defense of democracy and the rule of law. FILE - Nikki Tran of Washington, holds up a sign with pictures of Supreme Court Justices Thomas, Kavanaugh, Samuel Alito, Amy Coney Barrett, and Neil Gorsuch, as demonstrators protest outside of the U.S. Supreme Court, Tuesday, May 3, 2022, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

This is Part II of the "The Supreme Court’s War on the Future" Dig series

FILE - Nikki Tran of Washington, holds up a sign with pictures of Supreme Court Justices Thomas, Kavanaugh, Samuel Alito, Amy Coney Barrett, and Neil Gorsuch, as demonstrators protest outside of the U.S. Supreme Court, Tuesday, May 3, 2022, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

This is Part II of the "The Supreme Court’s War on the Future" Dig series

This is the concluding feature story in the multi-part Dig series, “The Supreme Court’s War on the Future,” investigating how the Supreme Court was remade in the image of Robert Bork.

The radical right’s long crusade to capture the Supreme Court is over. Anyone who doesn’t realize this hasn’t been paying attention, or has imbibed the Kool-Aid served by Chief Justice John Roberts at his 2005 Senate confirmation hearing, when he promised to work as a neutral arbiter on the bench much like a baseball umpire, calling only “balls and strike, and not to pitch or bat.”

Instead of minding the strike zone, Roberts and his Republican confederates old and new have changed the rules of the game in a concerted effort to drive the country backward. Under the aegis of the regressive legal theory of “originalism” (see Part I of this series), they have issued a blistering succession of reactionary rulings on voting rights, gerrymandering, union organizing, the death penalty, environmental protection, gun control, abortion, campaign finance, and the use of dark money in politics. Before the court’s current term concludes at the end of June, it likely will wreak more havoc in a series of pending cases on “religious liberty” and LGBTQ discrimination, affirmative action, student-debt forgiveness, and, once again, voting rights.

The court is at war with democracy and modernity. It must be stopped.

Instead of minding the strike zone, Roberts and his Republican confederates old and new have changed the rules of the game in a concerted effort to drive the country backward.

The good news is that from a legal standpoint, there is much that can be done to bring the court back into balance and restore its independence from the Republican Party and its dark money donors. We know what steps must be taken to fix the court. We need, among other measures, a code of ethics to root out corruption and conflicts of interests, as the Supreme Court is the only judicial body in the country whose members are not bound by one. We need term limits for the justices, and congressional overrides of far-right decisions to the maximum extent possible. Above all, we need to expand the number of seats on the court and fill them with contemporary-minded jurists who repudiate originalism in favor of “living constitutionalism,” the rival jurisprudential model that sees the Constitution as an evolving document.

Accomplishing any meaningful changes in the court’s composition and orientation, however, won’t come quickly or easily. Meaningful changes will require the support of a broad-based political movement that links the issue of court reform to legislative and grass-roots campaigns for social justice. This will be a long struggle waged across a variety of fronts — in courtrooms; over the airwaves, print media and the Internet; in the halls of Congress; in public meetings, teach-ins and demonstrations; and most decisively, at the ballot box.

* * *

Every successful political movement involves undermining the propaganda of the opposition. With that principle in mind, the first step we can take in building a movement to reclaim the Supreme Court is something every one of us can do as individuals: We can reject the myth that the court is apolitical. The sobering truth is just the opposite. Presidents nominate justices to advance political agendas. And once confirmed and vested with lifetime appointments, justices exercise extraordinary power, issuing rulings that affect all aspects of our lives, often acting as de facto super-legislators.

We can also abandon our reverence for the court’s presumed wisdom and scholarship. We may be legally bound by the court’s decisions, but there is no reason to regard the justices as infallible demigods deliberating on high. We can and should expose them as we would any other public servants or politicians, one by one and collectively, for producing poorly reasoned and result-oriented opinions, and betraying the public trust.

Washington Post columnist Perry Bacon Jr. has proposed a campaign of organized shaming as a short-term approach to reining in the court. “Democratic politicians, left-leaning activist groups, newspaper editorial boards and other influential people and institutions need to start relentlessly blasting Republican-appointed judges,” especially those on the Supreme Court, Bacon argued in a recent article.

Among other concrete actions, Bacon advises weekly news conferences convened by high-profile Democrats, including on occasion the president, to slam the court’s most extreme rulings. He also calls on the Senate Judiciary Committee to convene hearings “in the mold of the Jan. 6 commission, with compelling witnesses and videos. Republican-appointed judges have been just as damaging to American democracy as Trump has been (if not more so), just in a less obvious way. That needs to be explained to the American public…[in] plain-spoken” language. He also suggests that in those conferences and editorials, the justices be identified according to their partisan affiliations.

We can reject the myth that the court is apolitical. The sobering truth is just the opposite.

To a certain extent, the shaming and public criticism Bacon advocates is already underway. As a result of the court’s extreme shift to the right and the antipathy the shift has engendered, the court’s approval ratings have plummeted, triggering a crisis of legitimacy unseen since the early 1930s.

If done artfully, shaming can be a catalyst for change. But long-term, we need broader remedies and specifically, court expansion. To get a sense of the possibilities, we need to turn to history.

Contrary to much conventional thinking, our court system is not fixed in stone, but has evolved over time. We are not the first generation to confront the issues of judicial power and abuse.

Americans have been debating — and at times openly fighting over — the proper nature of judicial power since colonial times. Legal disputes over taxation, the issuance of general search warrants known as writs of assistance and expansions in the jurisdiction of the King’s dreaded Vice Admiralty Courts were key factors in sparking the American Revolution.

Three of the 27 grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence concerned the administration of justice. The signers of the declaration complained that George III, the British monarch, had deprived them of the right to establish their own courts, that he had made judges dependent on him for their salaries and tenures and that he had deprived them of the right to trial by jury.

The Articles of Confederation, our first national charter, marked the end of British rule, but did not create a national court system. That task was left to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, which established a tri-partite federal government with a separate judicial branch.

The Supreme Court is the only court specifically mentioned in the Constitution. Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution provides: “The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” The same section specifies lifetime tenure for all federal judges.

Nowhere does the Constitution say how many justices should sit on the Supreme Court. That decision is left up to Congress and the president through legislation passed and signed into law.

The Constitution is also silent on whether the Supreme Court should be endowed with the power of “judicial review” — the tool that authorizes it to invalidate or uphold acts of Congress, the president and the states at its sole discretion.

In the ratification debates that followed the Convention, the proponents and opponents of the new constitution put the concept of judicial review front and center in a clash of essays published by newspapers in New York and elsewhere that have since been collected and come to be known as the Federalist Papers and the Anti-Federalist Papers.

Writing under the pseudonym “Publius,” Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, outlined the principles of judicial review in Federalist No. 78, arguing:

“The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body.”

Hamilton was aware of the potential for overreach, but he believed the federal judiciary would in practice be “the least dangerous” branch of government. Unlike Congress and the executive, he reasoned, the courts would have “no influence over either the sword or purse,” but would possess “only judgment,” rendering them dependent on the other branches to obey and carry out their decisions.

Not all the founders agreed. Almost forgotten in the ensuing hagiography of Hamilton are a set of anti-federalist warnings believed by historians to have been penned by New York state judge Robert Yates under the pseudonym “Brutus” that seem eerily to have presaged the rise of today’s imperial Supreme Court.

In essay No. 14, Brutus wrote that under the Constitution, the Supreme Court “would be exalted above all other power in the government, and subject to no control.” In No. 15, he added:

“[T]he supreme court . . . [will] have a right, independent of the legislature, to give a construction to the constitution and every part of it, and there is no power provided in this system to correct their construction or do it away…. Men placed in this situation will generally soon feel themselves independent of heaven itself.”

Hamilton’s position triumphed and became official doctrine with the Supreme Court’s landmark 1803 decision in Marbury v. Madison. As of August 2017, according to the Congressional Research Service, the court had used the power of judicial review to invalidate 182 acts of Congress and 1,094 state statutes and local ordinances as unconstitutional. In addition, it had also overruled, in whole or in part, 236 of its prior decisions. The numbers in all categories have grown since then.

Throughout the decades, the court has exercised its power of judicial review for both good and evil purposes. In Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), it illustrated the darkest side of judicial review, invalidating the Missouri Compromise and declaring that Black Americans could never be citizens. It returned to the dark side in the early 1930s when it struck down key pieces of the New Deal. Last year’s Dobbs decision on abortion is another appalling example. By contrast, the court moved the country forward in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), overturning the regime of “separate but equal” that it had previously upheld in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Brown ushered in a brief period of enlightened judicial review under the guidance of Chief Justice Earl Warren (1954-1969).

As its power increased, the court occasionally encountered strong political pushback. Abraham Lincoln, for example, defied the court both in his decision to suspend habeas corpus during the Civil War, and with the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) in direct contravention of Dred Scott. Other notable confrontations involved the conflicts in the 1930s between a reactionary court and a Democratic Congress and president, and those sparked by southern racists against the Warren Court and the civil rights movement.

Political pushback has also come in the form of proposals to change the number of seats on the court. Between 1789 and 1869, the size of the court was altered seven times to “pack” or “unpack” the panel for partisan purposes. Originally designed as a tribunal of six, the number of seats has varied from a low of five in 1801 in the middle of a battle for control of the judiciary between the waning Federalist Party and the rising Democratic-Republicans to a high of 10 in 1863, when Lincoln expanded the court to counter the influence of Chief Justice Roger Taney, author of the Dred Scott disaster. The number has remained at nine since 1869.

* * *

Interest in court reform and expansion reemerged after Senate Republicans refused to hold a confirmation hearing for Merrick Garland, President Obama’s choice to replace Antonin Scalia, who died suddenly on Feb. 13, 2016. The interest picked up additional steam during the 2020 presidential campaign after President Trump succeeded in packing the court with young dogmatic originalists.

Although President Biden has never been a supporter of court expansion, he bowed to pressure from his left, and appointed a bipartisan blue ribbon commission of prominent academics and commentators to study the need for reform in April 2021. After seven months of meetings and deliberations, the commission produced a 294-page report but without making a single concrete recommendation.

On the plus side, the report contains a useful summary of the court’s history, including a discussion of the last significant attempt at expansion undertaken by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. FDR’s experience offers several important lessons for contemporary reformers.

Roosevelt sent his court plan to Congress on Feb. 5, 1937. Formally known as the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937, the measure would have allowed the president to appoint up to six new justices, one for every member of the high court older than 70 years, six months, who had already served 10 years or more and declined to retire.

Facing stiff resistance in the Senate, despite his overwhelming victory at the polls a year earlier, FDR turned to the public on March 9, 1937, in the ninth of his famous radio “fireside chats.” Throughout his four terms in office, FDR used such addresses to speak directly to the American people, to quell their economic and social anxieties, explain his policies and rebut conservative critics as he attempted to steer the nation through the Great Depression and, later, the Second World War.

The ninth chat began over the static-filled airwaves much as did those that preceded it, with references to the unrelenting hardships that, in FDR’s words, had left “one-third of a Nation ill-nourished, ill-clad, and ill-housed.” The president then turned to the need to reorganize the federal judiciary, and especially the Supreme Court.

Roosevelt and the militant industrial union movement that formed the heart of his New Deal base were outraged by a series of ultra-right-wing rulings from the high court that had struck down key pieces of New Deal legislation, including the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act and a New York state minimum wage law. In the coming weeks, the court was slated to issue decisions on the constitutionality of the National Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act. The president and his allies feared the worst from the “Nine Old Men,” as the septuagenarian justices who sat on the court were often called. They believed that unless the court changed course, it could and very likely would destroy the economy and along with it, democracy itself.

In language that today’s court reformers and “living constitutionalists” might recognize as their own, FDR told his audience:

“When I commenced to review the situation [with the Supreme Court] with the problem squarely before me, I came by a process of elimination to the conclusion that, short of amendments, the only method which was clearly constitutional, and would at the same time carry out other much needed reforms, was to infuse new blood into all our Courts. We must have men worthy and equipped to carry out impartial justice. But, at the same time, we must have Judges who will bring to the Courts a present-day sense of the Constitution — Judges who will retain in the Courts the judicial functions of a court, and reject the legislative powers which the courts have today assumed…

“Like all lawyers, like all Americans, I regret the necessity of this controversy. But the welfare of the United States, and indeed of the Constitution itself, is what we all must think about first. Our difficulty with the Court today rises not from the Court as an institution but from human beings within it. But we cannot yield our constitutional destiny to the personal judgment of a few men who, being fearful of the future, would deny us the necessary means of dealing with the present. This plan of mine is no attack on the Court; it seeks to restore the Court to its rightful and historic place in our Constitutional Government and to have it resume its high task of building anew on the Constitution ‘a system of living law.’”

The bill never was enacted. After months of heated debate, the Senate voted to send it back to committee, and the House never brought it to the floor. Ever since, the “court-packing plan,” as the scheme has been dubbed in mainstream historical narratives, has been seen as “the most humiliating defeat” of FDR’s career.

Except that it wasn’t a failure at all. On March 29, 1937, the Supreme Court did a complete about-face, upholding a Washington state minimum-wage statute similar to the New York law it had overturned the year before. In April, the court upheld the National Labor Relations Act, and in May, it validated the Social Security Act.

Over the next six years, eight of the Nine Old Men retired, allowing FDR to replace them, and to elevate one of the court’s liberals — Harlan F. Stone — to the post of Chief Justice. The court never again invalidated a New Deal program. FDR would later claim, “We obtained 98% of all the objectives intended by the court plan.”

Historians have debated the cause of the court’s turnaround, but pressure from the administration and the threat of intensifying labor unrest undoubtedly played a critical role. Indeed, on the morning of March 9, 1937, just hours before FDR’s chat, The New York Times ran two front-page stories about a new wave of “sit-down strikes” spearheaded by the United Auto Workers of America in Detroit and Flint, Michigan. The strikes, the paper reported, were “the most drastic…that the automobile industry has experienced,” halting production at factories owned by Chrysler, Chevrolet, Packard and the Hudson Motor Car Company. The workers eventually won, and the UAW was recognized as their bargaining agent.

We are faced today with echoes of the past — a Supreme Court that has moved sharply and unpopularly to the extreme right; an economy that is backsliding into ever-worsening oligarchy and is on the verge of a new recession; a world that is teetering on the brink of another global war.

What Might We Do?A number of organizations are leading the campaign to reform the Supreme Court, although not all call for expansion. Click on the links to learn more and get involved:

If anything, the need to expand the court is more urgent than ever. We don’t have Nine Old Men on today’s Supreme Court. Clarence Thomas will be 75 in June and Samuel Alito will turn 73 in April, but Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett are in their fifties, youngsters in judicial terms. They can be expected to serve for decades.

We also do not have a labor movement that can pressure the court. Only 10.1% of the American workforce is unionized, and, with some exceptions, it isn’t particularly militant.

We do, however, have the makings of a progressive coalition with far-reaching potential. Some of that potential was unleashed in the midterm elections, galvanized by the Dobbs decision. We need to merge that energy with movements organized around police violence, debt relief, voting rights, economic inequality and other causes that are stymied by the current Supreme Court.

Success, even in the long run, is by no means guaranteed. Basic court reform will require strong and aggressive Democratic majorities in Congress, and a Senate caucus prepared to abandon or carve out exceptions to the filibuster. In any event, we have no alternative but to push ahead. Either we accept a reactionary court for the foreseeable future, or we try to change it.

As University of Pennsylvania law professor Kermit Roosevelt III, Teddy Roosevelt’s great-great grandson, put it in a December 2021 article for Time magazine, “We are witnessing a minority takeover of our democracy,” with the Supreme Court standing in the way of progress.

Professor Roosevelt was a member of the Biden Supreme Court Commission. He began his stint there as a skeptic of court expansion, but the experience changed his thinking. He is now a staunch advocate. We can’t be intimidated or deterred “by wishful bromides about neutral judges and myopic defense of the status quo,” his article concludes. “Court expansion may be the only thing that will save our democracy for the next generation.”

Truer words could not have been written by FDR himself.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.