Part 6: Out of the Halfway House, and Then a Scare

After more than 30 years in prison and halfway houses, the 58-year-old author walks free in the world.

By Ronald W. Pierce

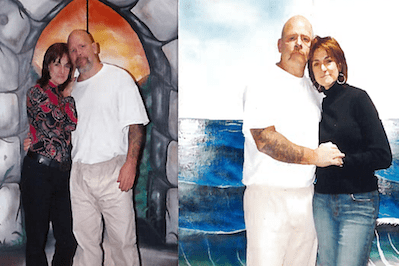

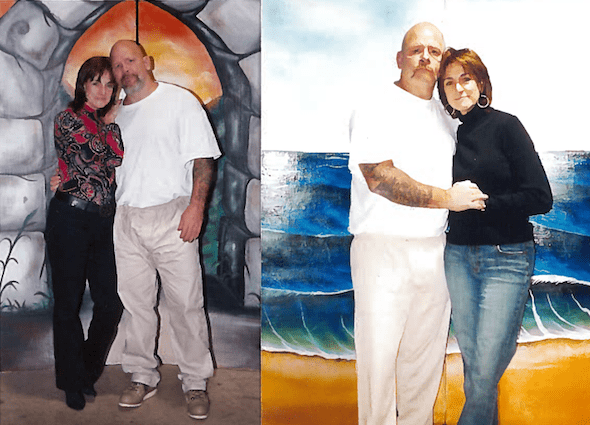

Ronald W. Pierce with Karen, his fiancée. (Ronald W. Pierce)

Editor’s note: This is the sixth story in a seven-part series exclusive to Truthdig called “Going Home.” Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 and Part 7.

It is Nov. 14, 2016. I am being released from the halfway house to go home. My two bags of clothes are packed. I also have a bag of books. I am awaiting the call to make the final journey out into the world.

“Time to go,” the counselor says.

It is 7:30 in the morning. My stomach is in knots. I am glad I have not eaten anything. I would be sick. I wait by the front door for my release. I see Karen and Chris Hedges, my professor from prison, waiting in the parking lot across the street.

“Pierce has been discharged,” I hear the voice on the radio say. “He is cleared to leave the facility.”

I step out of the front door. I see a tall, shapely woman, whose 58 years have not detracted from her beauty, coming toward the gate. It is Karen. I feel tears welling up. I fight the urge to cry. I do not want to lose my composure.

I struggle to get my bags of clothes through the revolving metal gate. I think of the irony of revolving doors. Finally, with Chris’ help, we manage to get my bags and myself on the other side. I am free. Karen feels good in my arms. I feel her trembling.

I let go of Karen and hug Chris. He has been with me every step of the way since we first met in 2013. I took a history class from him in 2015 and a philosophy class in 2016. He is a mentor and a true friend. It does not feel real.

“I will buy you and Karen breakfast,” he says.

“I am supposed to go straight to my parole officer,” I tell him.

I get into the front seat of Karen’s car. It is white. It has a foreign name, a Sentra or something like that. It feels small, very low to the ground. I feel like a giant getting into a midget car. It is difficult to swing in my legs. I finally manage.

Karen hands me a gift wrapped in beautiful paper, with a ribbon tied into a bow. I have never seen such a fancy wrapping job. I do not wish to mess it up by opening it. I pull at the ribbon. I don’t know how to open it. Karen slips the ribbon off for me. I tear away the wrapping and open the box. Inside, attached to an official New York Yankees keychain, are two house keys and the mailbox key for Karen’s home. There is also a poem. It is too personal to share. My eyes well up. I choke back tears. I cannot cry at every emotional moment or I will be out of tears before noon.

“Chris helped me with the words,” she says, “but the heartfelt meaning is mine.”

Karen and I drive to Red Bank. I walk up the stairs to the parole office. The receptionist greets me warmly and explains what documentation I need. I hurry down to get my folder and bring it back. She thanks me and tells me to take a seat.

I am nervous. This is my first meeting with my parole officer. I want to make a good impression. I want him to see the man I know myself to be, not the person first incarcerated all those many years ago.

I see a tall lanky man and a strong-looking blond woman through the receptionist’s window. They are conversing over a folder they are reviewing. I wonder whom they are discussing. A parolee comes in to see his parole officer. The door opens. The tall lanky man motions for me to enter. He introduces himself as a sergeant. He explains that the parole officer assigned to my case is on vacation.

“Officer Oliveri is going to do your initial processing,” he says.

The sergeant brings up my biker affiliations. He explains the difficulties that continuing such affiliations will cause me. I go back to the waiting room.

Officer Oliveri is the strong-looking blond woman. She introduces herself.

“The first thing we need to do is take pictures of your tattoos,” she says.

She tells me to remove my shirt. I am heavily tattooed. It takes time to complete the photo process. Next, we go into the bathroom. She explains the procedure for voiding a urine sample, and then leaves me alone.

“The test is positive for methamphetamines,” she says after testing the cup of urine.

I am livid. I know I am clean. I do not use drugs. My prescription medication would not test positive for crank.

“It must be a false positive,” I say. “Maybe something is wrong with the cup.”

Officer Oliveri calls in the sergeant. She asks him to check my cup.

“Yeah, definitely meth,” the sergeant says after he checks. “We can put you in an outpatient program, but if you deny this and it comes back positive from the lab, you are going to a rehab facility—if you are lucky. Best to come clean now.”

I am clean. I am one hour out of prison after 30 years, eight months and 14 days. I consider the options.

“This can’t be a positive test,” I say. “I do not use drugs. I will not lie and say I do, not even at the cost of my freedom.”

We finish the processing. They seal the cup. I am left alone for 20 minutes. I am advised of the conditions of my parole when they come back. I am given my next date to report. The address is in Toms River, a township in New Jersey.I return to the car and tell Karen what happened. We decide to find a place to draw blood for evidence. I call my brother Rodney, whom we were to meet for lunch. I explain what we are doing.

We go to the nearest the emergency room and pay for a blood test.

Then we go to L.L. Bean. I pick out a coat. It costs $130. Karen uses sales coupons and her charge card. We only pay $13. I am in awe.

We drive to my brother’s farm.

When we approach the house, I see my family outside. I have not seen most of them for more than a decade. My mother, once a strong, dark-haired Polish woman, is frail. Her hair is the color of snow. She is shorter than I remember. I get out of the car. We are all crying.

I hug my mother first. I notice she is now using a cane to walk. I do not want to let her go. She hugs me so hard it takes the breath from my lungs. I kiss her on top of the head.

“You got old,” I say.

“You ain’t no spring chicken,” she responds.

After a group hug, I hug each member of my family individually.

My mother says we are all going to the LongHorn restaurant, with 11 family members. I am overwhelmed. I go into the bathroom at the restaurant. I sit in the stall for a few minutes. Exhausted, I need to decompress.

When I return to the table, I unwrap my napkin. The forks seem so big. The sharpness of the knives makes me leery. I remember cutting myself with a plastic knife pilfered from the officers dining hall in prison. When the meals arrive, everyone wants to share their dishes with me. I am getting full. The steak is too large.

Just taste everything,” Karen says. “We can take the rest home in a bag. I need you around for a long time, sweetheart.”

I love my family, but I feel relief when Karen and I leave.

Karen takes me to ShopRite. I look at the fresh-produce section. It takes my breath away. Every fresh vegetable and fruit imaginable seems to available. I cannot decide what to buy. How do you choose only one or two vegetables when you have been deprived for decades?

We do some more shopping. Then we go home. I hold the key Karen gave me. I walk in the evening sky across the street to where we will live. I unlock the two locks on the front door. I lift Karen in my arms and carry her across the threshold. I close the door behind us. Home.

On Nov. 24, 2016, the day before Thanksgiving, I receive a call from the parole office. The drug test came back negative. I knew it could not have come back any other way, but these tests are not as reliable as they are made out to be. I feel relief. My life is starting to go right.

Part 7 of the “Going Home” series will be published on Truthdig on Tuesday.

Ronald W. Pierce served 30 years, eight months and 14 days in New Jersey prisons for murder. Released in 2016, Pierce now is living in Jackson, N.J., and completing his Bachelor of Arts study at Rutgers University. He is an honors student, majoring in justice studies with a minor in sociology.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.