One Community’s Fight To Recall School Board Culture Warriors

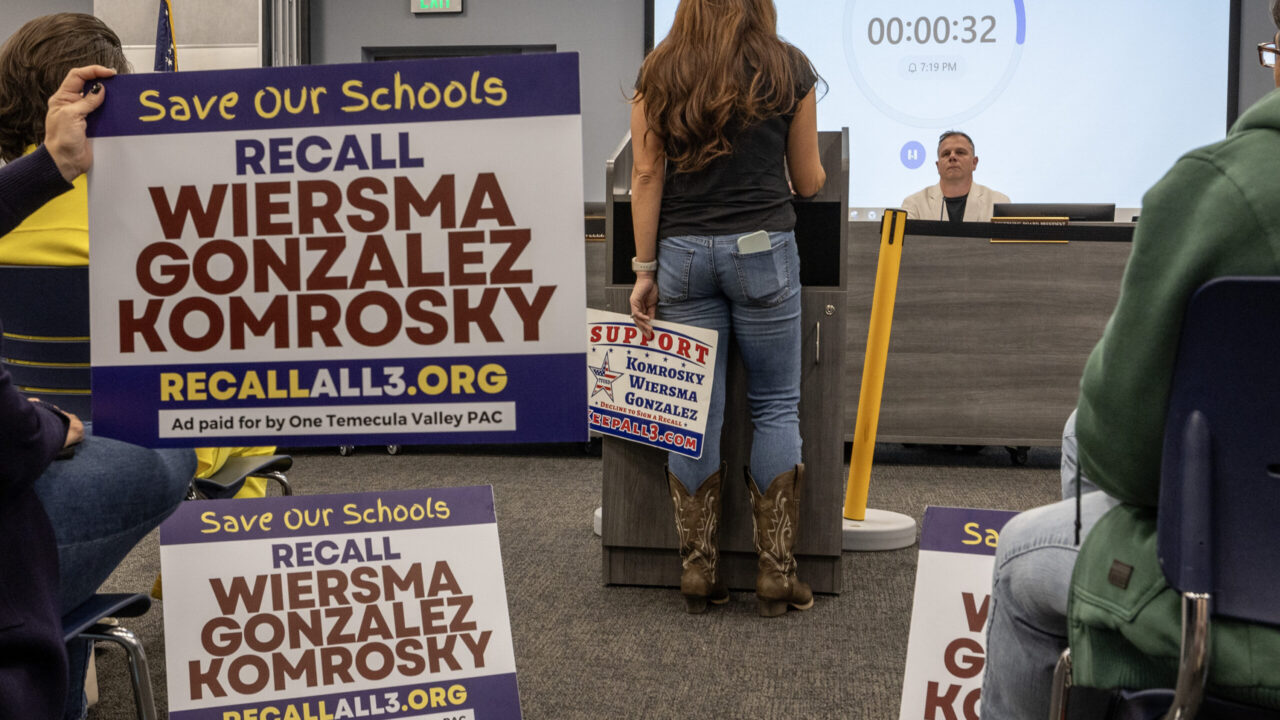

In Temecula, residents with different agendas united this year to remove members who attacked teaching on race and LGBTQ+ topics. Some Black recall supporters say the community has failed for decades to fight racism. A Nov. 14 Temecula Valley Unified School District board meeting. Photo by Barbara Davidson / Capital & Main

A Nov. 14 Temecula Valley Unified School District board meeting. Photo by Barbara Davidson / Capital & Main

On a warm, sunny Wednesday afternoon, a crowd gathered at the steps of Temecula’s civic center. The faces were young and old, and mostly white. Many carried signs with “RECALL” in bold, capital letters; others carried rainbow flags. As people milled about, a high school student sporting mushroom earrings made his way through the crowd handing out pins emblazoned with a rainbow and the words “You are safe with me.”

After a few minutes, a Black, 17-year-old Chaparral High School senior made her way to the top of the steps and addressed the crowd.

“The continued bigotry and ignorance displayed by the school board towards its Black community members are clear indications of the need for their recall … it is essential that we persevere in our efforts to hold the board accountable,” Brooklyn Anderson said to applause.

Moxxie Child, a 16-year-old white transgender student, spoke over the whoops and cheers. “I stand before you not just as an activist but as someone deeply concerned about the critical issues plaguing Temecula’s schools and students, jeopardizing our right to a quality education.”

The teachers, students, parents and community members, who were brought together by a group of local civic organizations, are pushing for the removal of the three-member majority of the Temecula Valley Unified School District’s school board.

Following months of stormy board meetings, student walkouts and a lawsuit filed on behalf of students, parents and teachers, many in this middle-class suburban city say they’ve had enough of the divisive policies and edicts enacted by their school board’s hard-right majority and have come together as One Temecula Valley PAC to demand a recall.

A group of mostly Black parents and students, united under the banner “ENACT,” supports the recall as well but believes much of the attention is focused on LGBTQ+ rights rather than recognizing and correcting the racial intolerance that has plagued Temecula Valley for decades.

It’s a fragile alliance between the two groups leading the recall, but one that has found common ground in their resistance to the board’s majority.

All three of the newly elected school board members were contacted for this story but did not respond to a request for comment.

The board’s conservative majority was powered to victory in 2022 with the financial backing of the Inland Empire Family PAC and the blessing of Tim Thompson, a Christian nationalist pastor and founding pastor of 412 Church Temecula Valley who has called public schools “Satan’s playground.”

In the new board’s first meeting in mid-December last year, Komrosky introduced a motion to ban the teaching of Critical Race Theory, a term that has become a dog whistle in conservative circles and refers to the discussion of the history and experiences of people of color. Komrosky’s motion called CRT “divisive” and “racist ideology” that “assigns moral fault to individuals solely on the basis of an individual’s race.” Komrosky also introduced a resolution that would ban racism in the district, a move teachers saw as an effort to block any discussion of racial intolerance.

Both of the resolutions were copied from motions adopted in the Paso Robles Joint Unified School District. The board later hired former Paso Robles school board member and author of those resolutions Christopher Arend, who is white, to make presentations to teachers on CRT.

The board meeting stretched for more than five hours in a packed auditorium, with parents, teachers and students protesting the resolutions. A handful of speakers, many of whom said they didn’t live in Temecula or have students in the district, spoke in favor of the resolutions.

Chris Lindberg, a fourth and fifth grade teacher at French Valley Elementary School, said the resolutions were an affront to the concepts of anti-racism.

The board’s conservative majority was powered to victory in 2022 with the financial backing of the Inland Empire Family PAC and the blessing of Tim Thompson, a Christian nationalist pastor and founding pastor of 412 Church Temecula Valley who has called public schools “Satan’s playground.”

“Pairing an anti-racism statement with something that says CRT would be wrong … being anti-racist means calling out racism when you see it and you hear it and working to prevent it,” Lindberg said. She warned the resolution “may result in teachers feeling unable to answer uncomfortable questions from students, or to have honest conversations and discussions about how race affects our lived experiences and is part of our educational journey.”

Jessica Jones, a ninth grader at Chaparral High School, echoed the sentiment. “Scholars and activists who discuss CRT are not arguing that white people living now are to blame for what people did in the past. They are saying that white people living now have a moral responsibility to do something about how racism still impacts all of our lives today,” Jones said. “If we ban this discussion of CRT in classrooms, we are repeating the same history so many people fought to have in the books.”

Despite the calls from the community and then-superintendent Jodi McClay to abandon the resolutions, both were adopted on 3-2 votes. McClay was later fired by the school board without cause.

Steven Schwartz, who is white and a longtime Temecula Valley school board member who voted against the CRT ban, says his new colleagues are following a right-wing playbook. “Basically they are anti-public education. They want us to fund Christian schools rather than public schools … teachers are infuriated.”

Since December 2022, Pride and Black Lives Matter flags were prohibited along with every other banner but the American and state flag; teachers were told to tell parents if their child was transgender or using new pronouns; and an aborted effort was made to remove gay rights icon Harvey Milk’s name from a social studies curriculum, with Komrosky incorrectly calling Milk a “pedophile.”

Several teachers and students who spoke out against the board’s recent actions have been targeted online by supporters of the board’s majority. Critics have seen personal photos and addresses posted online. Some say they have been followed at their homes or jobs. One teacher’s husband was branded a pedophile in a social-media post.

“I used to use my Instagram and Facebook almost as a digital historian of myself for my future grandkids,” Temecula Valley High School teacher Dawn Sibby said in a phone interview. “But I can’t do that right now. I can’t put up pictures of my family — I don’t want them to be attacked verbally or in any other way.”

Much of the community’s resistance to the school board’s actions has come from the One Temecula Valley PAC. The committee was created by Jeff Pack, a white onetime journalist who seeks to restore nonpartisanship to the school board. Its members include young parents, longtime residents and even prominent Republican politicians, including former Temecula mayors Jeff Comerchero and Maryann Edwards — the latter was once described as “the next Tea Party rock star.”

For years Pack said he’d wanted to do a story on the building political influence of Thompson and his 412 Church. In the 2022 elections, Thompson and the Inland Empire Family PAC spent thousands to bolster the profiles of far right political newcomers. “That changed the landscape because we had incumbents not doing much … we couldn’t put up a fight fast enough,” Pack said. Since the new school board members took office, he said he’s heard from voters who feel they were tricked into voting out the incumbents. “In the recall effort, a lot of people are saying, ‘Yeah, I got duped.’”

Heading up community outreach for the One Temecula Valley PAC is Julie Geary, a young white woman and longtime Temecula resident. Geary’s interest in local politics, like many others, was sparked in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd. She created a Facebook group called Temecula Unity, and began hosting events where local residents of color would share their experiences with city leadership. “So many people in City Council had never heard the stories of people who live in this city.” She also organized panels with the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department and Murrieta Police Department, as well as blanket drives and park clean-ups.

Geary’s interest in the school board began when Thompson, the pastor, became a vocal critic of a local masking mandate enacted in the early days of the pandemic. The election of Komrosky, Wiersma and Gonzalez pushed her to become even more involved because she saw them as “totally unwilling to compromise, to see someone from the other side.”

In the summer of 2022, Pack approached her to form the One Temecula Valley PAC. Pack said the long-term goal of the committee is to pay close attention to local politics — in the short term, the group is focused on the recall.

Pack said that the idea for a recall came from a group of Black moms who had a loose association with the PAC. His group began collecting signatures for the recall in June.

The three targeted board members have held their ground.

“I kept my campaign promise. To us, Critical Race Theory is divisive,” Komrosky said during a Fox News appearance. “It’s un-American.”

“[I] talked to families who want to see a back to basics approach in education — reading, writing, arithmetic, learning cursive. They don’t want to see political activism and divisive ideology,” Wiersma said in the same interview.

Not everyone is pleased with the One Temecula PAC, and for different reasons.

Mick Florio, whose granddaughter is a high school student in Temecula, said he believed the effort to recall the new members is “a waste of taxpayer money.” He does not agree with all of the district’s new policies. Although he supported the new outing policy and banning of flags, he said “aspects of CRT have a place in our history. It’s our history, but our history needs to be taught, good and bad.”

At a recent signature gathering event for the recall, a white man shoved a man signing the recall forms in clear view of a reporter and told him multiple times he would “go to hell.” The man, who identified himself as Brian but declined to give his last name, said that although he had never been married and has no children, he knew that “there is a battle here in Temecula.” He said he believes schools are indoctrinating children and giving students rights he thinks they should not have until they are 18. “I believe that the Christian has morality and we’re making decisions through the way God would have them done, versus everyone in the world is trying to push their stuff against us … There’s agendas out there that are just not healthy for society,” he said.

He then echoed an Adolf Hitler quote published in a newsletter by the far-right group Moms for Liberty. “Ultimately, the idea is just like Hitler’s time. What did he do? First he indoctrinated the kids and then made them killing machines,” he said. Moms for Liberty has since apologized for printing the quote.

At an event for Black parents and students held at Memelli Sports Bar (one of Temecula Valley’s few Black-owned restaurants) in mid-September, several parents expressed skepticism that recalling school board members would halt the racism they say their children face in schools. Some recalled facing racist harassment themselves as students in the area.

Temecula has a history of racial inequality dating back to its establishment as a city. The wider Temecula Valley was home to the indigenous Luiseño people until 1875, when they were evicted by court order. Black, Chinese and Indigenous people were subjected to discrimination in public transportation, theaters, restaurants and hotels, and they faced open hostility from whites in the area. Nearby Hemet was a sundown town through at least the 1960s, with Black people prohibited from staying overnight. In the 1980s, Ku Klux Klan leader Tom Metzger founded a white supremacist group in nearby Fallbrook. Local newspapers reported on violence linked to local neo-Nazis in the area throughout the 1990s.

More recently, in 2019, a 17-year-old Black student at Temecula Valley High School was targeted with racist graffiti scrawled across a pair of doors on the school’s campus. In 2021, the high school made headlines again when students yelled racial slurs at visiting cheerleaders during a football game.

During the early days of the pandemic, a white councilwoman angered many when she compared herself to civil rights icon Rosa Parks for fighting the mask mandate. The same woman, Jessica Alexander, attempted to make the city a “sanctuary city” for the unborn. In January, Alexander and two other City Council members voted to cease honoring federally recognized heritage months, including Black History, Women’s History, Pride, Asian American and Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander, Native American Heritage and Hispanic Heritage months.

“Race is not our thing here. It has to be taken care of in the church. I can’t be your therapist,” Alexander said during the vote.

Brandie Kekoa, a Black mother of two and local business owner, has lived in Temecula for nearly her entire life. She went to Temecula Valley High School in the 1990s, and left town for a brief period but returned once she married her childhood sweetheart to be near her parents. Now her daughter, Genesis, is enrolled in the same school, experiencing the same things she went through.

“It’s always been racist. Black kids have always been mistreated in this town from the beginning, and no one has ever done anything about the mistreatment.”

At a recent signature gathering event for the recall, a white man shoved a man signing the recall forms in clear view of a reporter and told him multiple times he would “go to hell.”

Amy Eytchison, a white elementary school teacher who has taught in the district for over 25 years, agrees that Black families and their kids have been treated differently. “I think people would say things like ‘those kids’ … looking back, we could have done better.”

After the school board banned Critical Race Theory, Genesis, who is president of the Temecula Valley High School Black Student Union, led a walkout in protest. While distributing flyers to other students, Brandie Kekoa said, her daughter was attacked by a white male student who called her a “black bitch.”

The day of the protest, while watching Genesis lead a group of some 300 students across the street, Kekoa said she saw food being thrown at her daughter. Since then, Kekoa has seen her businesses’ bank accounts hacked and her personal information distributed on social-media profiles supporting Komrosky, Wiersma and Gonzalez. Genesis said she has had her job’s address shared on the pages as well, and she has been followed at work at least once.

Kekoa says that her family and the area’s Black community have not felt the same level of support on issues involving racism compared to the outspoken support of LGBTQ+ rights. Before the recall campaign, “People that are more moderate left stayed quiet with the racism,” she said.

Members of ENACT, a group of Black parents and community members dedicated to closing the achievement gaps in Temecula’s schools, agree with that sentiment. At Memelli Sports Bar, Stephanie Love, an organizer with ENACT, explained it was their group’s idea to recall the board members and they had initially worked with the One Temecula Valley PAC.

However, they decided to work separately after several members concluded their concerns were not prioritized by the One Temecula Valley PAC. Love said that ENACT supports the recall, but isn’t assisting the political action committee’s signature gathering efforts — they are collecting signatures on their own.

Pack estimates the One Temecula Valley PAC has gathered over 4,000 total signatures as of early November. The recall must collect signatures of at least 20% of registered voters in each school board member’s district — about 12,000 total by Dec. 8. If they succeed, the recall will be put on the ballot, either in a special election or the June primary.

Geary, like many others, is confident the efforts will succeed because enough local voters believe “you can’t wage your national political agenda in these school districts,” she said.

Copyright 2023 Capital & Main

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.