On Becoming Black, Becoming White and Being Human: Rachel Dolezal and the Fluidity of Race

When I think of the former NAACP official’s attempt to pass for black, I am reminded of my cousin Ernest, who successfully passed for white for four decades, and the fact that race in the United States -- though a mutable social construct -- remains more important than ever to the way we see ourselves. When I think of the former NAACP official’s attempt to pass for black, I am reminded of my cousin Ernest, who successfully passed for white for four decades, and the fact that race in the United States—though a mutable social construct—remains more important than ever to the way we see ourselves. Library of Congress

Library of Congress

For decades, no one knew my cousin Ernest Torregano was black. At least, no one who mattered in his new life.

Not the clients or associates of the prominent bankruptcy law firm with which he had built his reputation and his fortune. Not the other members of the San Francisco Planning Commission, of which he had been president. And certainly not the mayor, Elmer Robinson, with whom Ernest had been close since their days as fresh new lawyers in the city. It is quite likely, I think, that Ernest never admitted, even to Pearl, his second wife of 30 years, that she had married an African-American man.

Few understood the true extent of my cousin’s labyrinth of secrets until he was already dead and buried. By then, he had successfully “passed for white” for more than 40 years.

When his only child, Gladys Stevens, learned that her father had not died in 1915 but had been alive until 1954, she filed suit to claim her share of his estate — worth about $300,000 then, or about $2.6 million today. After a protracted legal battle to prove she really was Ernest’s daughter, she won. Meanwhile, her story — and Ernest’s — made national headlines for nearly seven years. One Oklahoma newspaper announced: “Widow Claims Rich Lawyer Was Really Her Negro Father.” A Connecticut paper proclaimed: “Daughter’s Suit Reveals Double Life of Man Who Passed Over Color Line.” But Newsweek magazine’s headline captured the essence of the story in just three words: “The Second Man.”

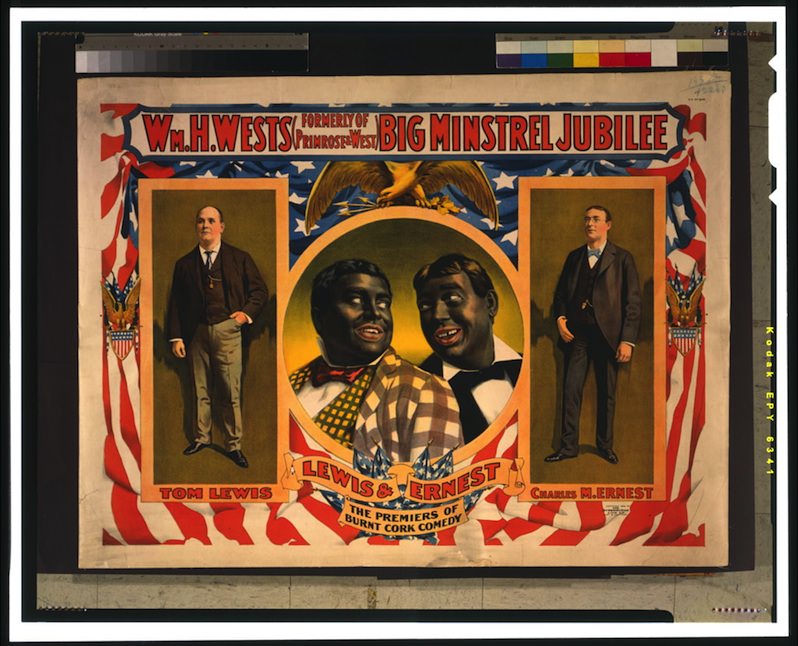

Born into a mixed-race family in New Orleans in 1882, the First Man was the fair-skinned son of a white father and a mixed-race mother. And because he so loved to sing and to laugh and to travel, he joined a touring minstrel troupe, performing in blackface makeup for cheering crowds across the South. In that show, he met Viola, who played the guitar, and they married. After their daughter, Gladys, was born, the First Man took a job as a Pullman porter on the Southern Pacific Railroad line from New Orleans to San Francisco — to make a better living for his new family. But at some point along the way — perhaps as he gazed through a train car window at the countryside rolling by or as he wandered along Market Street among white people who did not sneer at him or call him “boy” — he decided he would never return home. (According to one account, his mother, who supported the idea of his passing, convinced him that Viola and Gladys had been killed and that he should forget them forever.)

The Second Man was a different sort of minstrel altogether. He loved opera and chess, he belonged to numerous exclusive clubs, he spoke frequently to Francophone groups about the conditions in Nazi-occupied France during World War II, and at one point he reportedly gave a lecture in Spanish on the origin of the word “California.” For a time, the Second Man also kept a second address — to receive mail from his “colored” family and friends — and nearly lost his temper when his half-brother Edgar paid a surprise visit to his law office in the famed Mills Building in San Francisco’s Financial District.

As I grew up in the 1980s and ’90s, I never heard mention of any lawyer named named Ernest Torregano. I first learned about him when my grandmother, Juliette Torregano Joseph, said she had once read about a mysterious man from New Orleans with the same name as her grandfather, and that she knew they must be related somehow. After some digging through archival records, I discovered that they were. Interestingly, I also discovered that her grandfather’s family may have chosen to pass for white as well — or even simply been mistaken as such: In census records, they were listed as “white” in 1910, “mulatto” in 1920 and “Negro” in 1930.

I am sure there were other unknown people who passed out of my extended African-American family and into a world of whiteface. Even today, I can easily think of several relatives who could do so. I am reminded of my cousin Ernest and those unnamed others when I see yet another minstrel, Rachel Dolezal — the disgraced former head of the Spokane, Wash., chapter of the NAACP — with her fake frizzy hair and fake tan complexion, saying on national television that she chooses to “identify as black,” though none of her immediate ancestors were.

Her decisions, though bizarre, problematic and maybe even dangerous, raise important questions for me about race, as an idea and as an experience, in our country. Some of those questions are for Dolezal herself, and will probably never be answered, like: “Why are you really doing this?” Other questions are for myself and for society at large, like: “What is this social construct we call race?” and “Will there ever be a time — as Haile Selassie famously put it — when the color of a man’s skin is of no more significance than the color of his eyes?”

Science tells us that race is not a biological reality but a socially constructed one. (After all, humans came from Africa and all of us can probably trace our ancestry to someone, however distant, who would be considered black in modern times.) And because race is a social construction, many of our daily perceptions and experiences of it are based on what we see. When you or I — or the police — look at someone like Michael Brown or Eric Garner or Rekia Boyd or Rachel Dolezal — we assign them a racial category and treat them accordingly.

In her work for the NAACP, Dolezal was black as long as the people around her agreed that she was, just as we collectively agree that rectangular strips of paper and flat, circular bits of metal are money. Since her outing by relatives, Dolezal is not black so long as society chooses not to see her that way anymore. But it is undeniable that Dolezal did for some time successfully pass for black. And because she was perceived as black within her own community, she undoubtedly experienced at least some aspects of the daily slights and discrimination that come with blackness in this country — whether her claims regarding threats, hate mail and nooses are true or not. In that sense, because so much of how we categorize people is based on what we see, Dolezal was black for a time, just as my cousin Ernest, by presenting himself in a certain orchestrated way and spinning a complex web of lies, was white — because he was perceived as such and thus had gained the privileges of whiteness.

We may feel that race is immutable, but history has proved it to be an amorphous and constantly shifting idea.

For Daniel Sharfstein, a professor of law at Vanderbilt University, “what defines who is white and what defines who is black has always changed over time.”

Until 1895, he told me in an interview, “you could be black in North Carolina and walk across the border and be white in South Carolina” — because of the states’ differing legal definitions of blackness.

As a bevy of scholars has noted, race passers have a long history in the United States, including whites who passed for black. In some instances, the passers were white journalists who went undercover, posing as black to investigate racism in the South. Those investigations are described at length in Pulitzer Prize winner Ray Sprigle’s 1949 book “In the Land of Jim Crow” and John Howard Griffin’s 1961 book “Black Like Me.”

But there are many other examples.

“We can go back 200 years and find white women who swore they were African-American so they could marry black men without fear of persecution,” Sharfstein said. Later, during the Harlem Renaissance, he noted, the white wife of the conservative black journalist George Schuyler said she had found it was just easier for her and the other white women she knew in interracial marriages to say they were light-skinned.

In “Passing Strange: A Gilded Age Tale of Love and Deception Across the Color Line,” Martha Sandweiss, a professor of history at Princeton University, writes about Clarence King, a 19th-century white geologist and explorer from a prominent family in Newport, R.I., whose father was a wealthy trader. King lived for years as James Todd, a black railroad worker, in order to pursue a common law marriage with an African-American woman named Ada Copeland, who learned her husband’s secret only as he lay dying.

But Sandweiss makes a distinction between what King did, at a time when there were laws that prescribed racial boundaries, and what Dolezal has done.

“We need to think really differently about passing in the past as opposed to identity appropriation or identity shifting that we see now,” she told me. “Now we no longer have those legal lines.”

Instead, “the categories that are being transgressed are social and they are cultural,” she said. “They are lines that lots of people intuitively think they understand” — and thus they believe they “have a right to police who crosses in and who crosses out.”

Some researchers — like Marcia Alesan Dawkins, a communications professor at the University of Southern California Annenberg and the author of “Clearly Invisible: Racial Passing and the Color of Cultural Identity” — have argued that passing is something we all do.

“Everyone passes in some form or another,” Dawkins told me, “whether it’s in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, religious or political affiliation, sexuality, age, class, nationality, ability or state of mind.”

But in Dolezal’s case, “passing represents both a profound creativity and lack of creativity on her part,” she said. “The creativity comes from creating a believable persona. … The lack of creativity is that in order to fight racism she clings to the very ideas about race and identity politics that contribute to the problem — that biological race exists and that it’s race, rather than a racist cultural, political and economic system that makes people different.”

According to her research, Dawkins added, people pass either because they want to achieve some important goal or to, paradoxically, become the person they feel they truly are. For Dolezal, both factors seem to be in play.

Perhaps what is most perplexing about her choice, though, is that it seems so unnecessary.

“In many ways, this feels like the ultimate throwback,” Sharfstein said. “In 2015, it’s beyond debate that white people can form meaningful relationships with African-Americans. They can study and teach black history and black culture, and they can raise black children without any reason for them to feel compelled to claim they are African-American. … You can find countless white people who have sacrificed all kinds of things, including their lives, without having to make the choices she has made.”

Yet Dolezal “did feel compelled to do this,” he said, “at a time when racial categories should matter less than ever before.”

Though the racial categories may arguably matter less than they once did, for millions of Americans, social and cultural lines still remain vitally important. The point is illustrated, in part, by a 2014 analysis of the census forms of 168 million Americans. In the study, the Pew Research Center found that more than 10 million people had checked different racial or Hispanic-origin boxes in the 2010 U.S. census than they had checked in the census 10 years prior. In particular, the study showed, Hispanic Americans are increasingly identifying themselves as white.

“The data provide new evidence consistent with the theory that Hispanics may assimilate as white Americans, like the Italians or Irish, who were not universally considered to be white…,” Nate Cohn wrote in The New York Times. “The data also call into question whether America is destined to become a so-called minority-majority nation, where whites represent a minority of the nation’s population. Those projections assume that Hispanics aren’t white, but if Hispanics ultimately identify as white Americans, then whites will remain the majority for the foreseeable future.”

As we have so vividly witnessed in video footage of recent police killings of unarmed blacks, the very existence of racial lines remains important for black Americans because those lines can so easily tip the balance in favor of life or death. But the lines are also guarded for sometimes less-than-noble reasons within the black community itself by the use of labels like “whitewashed,” “Uncle Tom” and “Oreo.” The latter, for instance, is a derogatory term used for an African-American who is considered to be disloyal to the black community because he or she is “black on the outside and white on the inside.”

Interestingly enough, many African-Americans who have chosen to pass for white might take umbrage at the questioning of their loyalty, as many of those very same people have been involved in movements for social justice and racial equality. As Dolezal herself wrote in her June 15 resignation from the NAACP, she maintains her “complete allegiance to the cause of racial and social justice.”

Vanderbilt’s Sharfstein notes that it is common for passers to have been engaged with civil rights activism at some point in their lives.

“You see story after story where people are deeply engaged with the struggle for civil rights, then at some point in their lives, they give into despair or resignation and fade away,” he said.

In his book “The Invisible Line,” Sharfstein describes the Walls, a light-complexioned Washington, D.C., family committed to black civil rights during the years of Reconstruction. Yet by the beginning of the 20th century, he writes, they had all chosen to pass for white.

Many heroes of the African-American experience have been forgotten because their descendants chose to pass for white, Sharfstein added.

Even my cousin Ernest, after race riots in Oklahoma in 1911, penned an impassioned front-page opinion piece in The Chicago Defender, a storied black newspaper, decrying laws that enforced segregation, restricted voting, and prohibited interracial marriage and cohabitation. The piece’s extended headline even urged that “blacks should disregard the law.” However, a short time thereafter, my cousin had abandoned his family in New Orleans and was living as a white man in San Francisco.

Should we condemn all of those who pass? I think the answer is not always so clear-cut.

When it comes to my cousin, I was surprised to learn that his daughter, Gladys, wrote in a 1957 Ebony magazine article that she was “glad” her father had passed “because people would not have let him be what he finally proved he could be if he had said he was a Negro.”

I think there are times when we all have wished — however briefly — that we could be someone else. I am a proud black man — by ancestry and appearance, and I am even militant at times — yet I can say that there have been brief moments in my life when I have wished to be white: like that first time in the early 1990s, on the playground at school, when a white girl spat the word “nigger” in my face; or years later, when the parents of two white girls I asked out to high school dances forbade them from going with me.

On that score, I can at least understand, though not forgive, someone — like my cousin Ernest or the increasing numbers of Hispanics who are checking the “white” race box — who might be tempted to “cross over.” But when it comes to Dolezal, as others have pointed out, there seems to have been no good reason for her to take on a black identity — not to raise her black children, not to marry a black man, not to teach black history and certainly not to advocate for racial equality. (In fact, there is currently another white NAACP president, Donald Harris of Phoenix.) In addition, I am baffled by her choices because she must have realized that there would be controversy and condemnation if she were ever outed.

Still, I do not find her actions as deeply or personally offensive as many do. No matter how she wears her hair or how dark she keeps her complexion, the fight for racial equality must and will continue until, I hope, some day — so hard to imagine now — when privileges and punishments are no longer meted out by race or color and when checking color boxes on census forms seems absurd and unnecessary.

I look forward to that time, when I hope the curtain will have fallen on the last American minstrel show.

Channing Joseph, based in San Francisco, is one of Truthdig’s editors as well as an MTV News correspondent covering social justice issues. His stories have also been featured in The New York Times, The International Herald Tribune, The Atlantic, U.S. News & World Report, Entertainment Weekly, The Washington Post, People, CNN and BET.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.