Oliver Sacks, Neurological Innovator and ‘Awakenings’ Author, Dies at 82

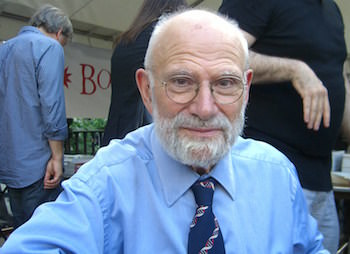

Hollywood might have granted him fame, but the renowned psychiatrist's valuable work deserved to be amplified, however the means. Neurologist and author Dr. Oliver Sacks at the 2009 Brooklyn Book Festival. (Luigi Novi / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY 3.0)

Neurologist and author Dr. Oliver Sacks at the 2009 Brooklyn Book Festival. (Luigi Novi / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY 3.0)

Hollywood might have granted him fame, but Dr. Oliver Sacks’ valuable work deserved to be amplified, however the means. The renowned psychiatrist and author of “Awakenings” died Sunday in New York City at 82. The cause of death was cancer, a terminal diagnosis that he eloquently confronted in a column for The New York Times in February.

Sacks’ explorations of the human mind often crossed over into artistic territory, as Variety described in an obituary Sunday:

Sacks had a gift for explaining complicated scientific concepts related to his study of brain functions to general readers. “Awakenings,” his first non-fiction book to achieve popular success, revolves around a group of patients in the Bronx whose lives are changed by a cutting-edge treatment for a rare form [of] encephalitis, aka “sleeping sickness.”

The film adaptation directed by Penny Marshall earned Oscar nominations for best picture, for lead actor for De Niro and for adapted screenplay for Steve Zaillian.

Sacks’ book “The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat,” a collection of stories about his clinic practice, was adapted as an opera in the U.K. by composer Michael Nyman in 1986.

“The Last Hippie,” an essay Sacks wrote that appeared in the “Review of Books” in 1992, was adapted into film “The Music Never Stopped” in 1992.

The Guardian’s tribute took a more literary approach in chronicling Sack’s contributions:

Where Balzac’s Human Comedy is filled with insights into the struggles of the youth from the provinces in the corrupt capital, or of the far too pleasure-loving young poet, Sacks’s human comedy presents the tragic case of the musician Dr P who develops visual agnosia and fails to recognise ordinary objects, in the process mistaking his wife for a hat; or the “extinct volcanoes” of Awakenings, people frozen by the encephalitis epidemic of the 1920s and only woken in 1969 by Sacks’s administration of the drug L-Dopa; or the tics and passions of a Tourette’s syndrome patient; or the world of the deaf who can “see” voices; or the autistic boy who is a draftsman of genius. Sacks’s clinical tales are the quintessential literature for our medicalised times.

Inspired by that other great neurologist Sigmund Freud and his case histories and autobiographical book on dreams, as well as the “neurographies” of the Russian psychologist Alexander Luria, Sacks was also an inveterate keeper of journals and a brilliant memoirist.

In his New York Times piece on facing his death, entitled “My Own Life,” Sacks memorably put a point on his story as he closed his column: “Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure,” he wrote.

–Posted by Kasia Anderson

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.