Not One Tree: Stopping Cop City

Reflections on the efforts to stop Cop City in Atlanta and on the state's efforts to silence voices of dissent. A demolished bike path is shown in the South River Forest near the site of a planned police training center in DeKalb County, Ga., on March 9, 2023. (AP Photo/R.J. Rico)

A demolished bike path is shown in the South River Forest near the site of a planned police training center in DeKalb County, Ga., on March 9, 2023. (AP Photo/R.J. Rico)

THE SUN HANGS LOW AND RED like a stoplight over the city. Ten thousand cars idle and litter down Moreland, another interminable avenue, vanishing onward in one-point perspective until the city thins out into strip malls, retail chains, junkyards, and Thank God Tires, where mountains of rubber shimmer in the summer evening heat. It is June 2021, and rush hour in Atlanta, when we drive to the forest for the first time.

The parking lot is half full. A cardboard sign at the trailhead reads LIVING ROOM → in Magnum Sharpie, so we start up the bike path, where a trail of glow sticks hangs from the trees. A quarter mile later, sky darkening in the distance, the glow sticks veer off to the left down a footpath, which zags through logs and opens onto a clearing in the pines. People with headlamps settle onto blankets, popping cans and passing snacks. A dog in a dog-colored sweater chases a squirrel and stands there panting. There is pizza piled tall on a table. Syncopated crickets. A giggling A/V club pulls a bedsheet taut between two trees, angling a projector powered by a car battery just so.1

Princess Mononoke, which we watch tonight reclined on the pine straw, is a parable about humans and nature. An Iron Age town is logging an enchanted forest to manufacture muskets. Our prince has been cursed, which is to say chosen, to defend the forest against the destroyers. Will the ancient spirit creatures deep in the woods be able to stop the march of progress? Cigarette smoke swirls in little eddies through the projector beam. The dusk is gone. There are no stars. Fireflies spangle the underbrush. The boars stampede the iron mine, squealing, “We are here to kill humans and save the forest!” The humans on the forest floor around us laugh and cheer.

* * *

THIS FOREST IS a squiggly triangle of earth, four miles around, some five hundred acres, lying improbably verdant just outside Atlanta’s municipal limits. Bouldercrest and Constitution Roads are the triangle’s sides, Key Road its hypotenuse. The surrounding mixed industry indexes the American economy: an Amazon warehouse, a movie studio, a truck repair shop, a church, a tow yard, a dump, a pallet-sorting facility, a city water-treatment plant. Suburbs, mostly Black and middle-class, unfurl in all directions. Prison facilities—juvenile, transitional, reentry—pad the perimeter, removed from Constitution Road by checkpoints, black mesh fencing, and tornadoes of barbed wire.

Viewed from above, the forest triangle is bisected once by a flat straight strip clear-cut for power lines and then again by Intrenchment Creek. This skinny, sinuous waterway is a tributary to Georgia’s South River and swells with sewage from the upriver city whenever it rains. Intrenchment Creek also marks the property line that splits the forest in two. East of the creek is the 136-acre public-access Intrenchment Creek Park, with a parking lot and bike path and hiking trails through meadows and thickets of loblolly pine, and also a toolshed and miniature tarmac where the Atlanta RC Club flies. West of the creek is the site of the Old Atlanta Prison Farm.

For seventy years, Atlanta forced incarcerated people to work the land here, growing food for the city prison system under conditions of abuse and enslavement both brutal and banal. Since the prison closed quietly in the 1990s, its fields have lain fallow, reforesting slowly. Though it’s DeKalb County, this parcel belongs to the neighboring City of Atlanta. It is nevertheless not public property. The driveway to the old prison farm has long been fenced off. The only way in is to scrabble up the berm from Key Road. Or cross the sloping, sandy banks of the creek from the public park and trespass onto no-man’s-land.

Will the ancient spirit creatures deep in the woods be able to stop the march of progress?

For years, the South River Forest Coalition lobbied Atlanta to open this land to the public and make it the centerpiece of a mixed-use megaforest: a 3,500-acre patchwork of parks, preserves, cemeteries, landfills, quarries, and golf courses linked through a network of trails crisscrossing the city’s southeast suburbs. And in 2017, it seemed like a rare success for grassroots environmental activism when the Department of City Planning adopted the Coalition’s idea into their vision for the future of Atlanta. You should see the glossy, gorgeous, four-hundred-page book the city planners published unveiling their plan for a city of affluence, equality, cozy density, affordable transit, and reliable infrastructure for robust public spaces. We no longer thought optimism like this was even possible at the scale of the American metropolis. Even if the dream of the South River Forest had been downsized, the 1,200-acre South River Park was still far from nothing. The book called it “the enduring and irreplaceable green lungs of Atlanta,” “our last chance for a massive urban park,” and a cornerstone in their vision of environmental justice.

How simple things seemed back then! In 2020, local real estate magnate Ryan Millsap approached the DeKalb County Board of Commissioners with an offer to acquire forty acres of Intrenchment Creek Park in exchange for a nearby plot of denuded dirt. Three years prior, Millsap had founded Blackhall Studios across Constitution Road and now was eager to expand his already giant soundstage complex into a million square feet of movie studio. This is no longer unusual for the Atlanta outskirts. State-level tax breaks have lured the film industry here. Since 2016, Georgia has produced at least as many blockbusters as California. As part of the deal, Millsap promised to landscape the dirt pile into the public-access Michelle Obama Park.

Neighbors had already begun to organize to sue DeKalb County for violating Intrenchment Creek Park’s charter when in April 2021, Atlanta’s mayor, Keisha Lance Bottoms, announced a plan of her own. On the other side of the creek, the city would lease 150 acres of the land abandoned by the prison farm to the Atlanta Police Foundation, because the old police academy was falling apart and covered in mold. Cadets were doing their push-ups in the hallways of a community college. The lease would cost the police $10 per year for thirty years. The new training center would cost $90 million to build. But only a third of this would come from public funds, the mayor assured the taxpayers. The rest would be provided by the Atlanta Police Foundation—which is not the Atlanta Police Department, but a “private nonprofit” whose basic function is to raise corporate funds to embellish police powers.

REST IN PEACE RAYSHARD BROOKS still practically gleamed in white spray paint on Krog Street Tunnel. The Atlanta police had killed Brooks during a confrontation in the parking lot of a Wendy’s not far from the forest barely two weeks after Minneapolis police killed George Floyd. The nation was still reeling after the upheaval of 2020—and now the mayor of Atlanta wanted not only to give $90 million to the murderers, but to clear-cut a forest to accommodate them. At first we were less indignant than insulted by the project’s intersectional stupidity. Hadn’t the city just agreed to invest in people’s leisure, pleasure, health, and well-being? Instead, the old prison farm would become a new surveillance factory.

In May, some two hundred people showed up to an info night in the Intrenchment Creek Park parking lot. A hand-painted banner fluttered from the struts of the gazebo: DEFEND THE ATLANTA FOREST. There were zines and taglines: STOP COP CITY. NO HOLLYWOOD DYSTOPIA. FUCK THE METAVERSE, SAVE THE REAL WORLD! The orgs were there with maps and graphs. #StoptheSwap detailed the Blackhall–DeKalb deal. The South River Watershed Alliance explained how the forest soaks up stormwater and wondered what would happen to the surrounding suburbs when the hilltop became a parking lot. Save the Old Atlanta Prison Farm narrated a mini-history of the land. Before the city prison farm, it had been a slave plantation.

People mingled, ate vegan barbecue. The cumbia lasted past dark. Half the audience had never been to the forest before, but now wanted to protect or maybe even enjoy it. History has apparently already decided that the movement was started by these organizations—but do you see those young people pacing the parking lot? Ask an anarchist. They all know who painted the banners, who printed the zines, who organized the inaugural info night. Who barbecued the jackfruit, who hauled in the speakers, who gave the movement its slogans and myths and indefatigable energy. Who got neighbors and strangers together to do something more than post about it. Who transformed concerned citizens into forest defenders.

* * *

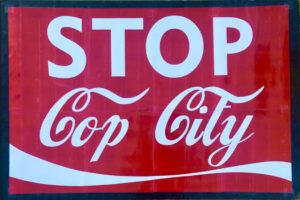

FOR A CITY OF MIRRORED SKYSCRAPERS, of fifteen-lane highways, of five million people and building ever faster, Atlanta is run like a small town, or a bloated feudal palace, royal families overseeing serfs sitting in traffic. For almost a century, a not-so-secret compact has governed the city town council–style, bequeathing positions in the power structure along dynastic lines. The roles at the table are fixed: mayor, city council, Chamber of Commerce, Coca-Cola, the police, the local news, and, uniquely and importantly in Atlanta, miscellaneous magnates of a Black business class. The biracial, bipartisan, business-friendly, media-savvy, moderate, managerial tradition the group perfected during the golden age of American capital is called the Atlanta Way.

This coalition steered the city through the tumultuous 20th century, holding things together with the blossoming optimism of economic growth. Desegregation happened in Atlanta unevenly, incompletely, but relatively uneventfully—which does not mean without shocking drama, racist recrimination, or moments of lurid violence. But compared with Montgomery or Memphis, the city was never bloodied in Civil Rights struggle. Even Martin Luther King Jr., its most famous martyr, was assassinated elsewhere. Jim Crow, white flight, gentrification all happened under a top-down, lockstep, synchronized city administration depressurizing the national conflict compromise by compromise: a golf course here, a swimming pool there, neighborhoods blockbusted one at a time.

Ask an anarchist. They all know who painted the banners, who printed the zines, who organized the inaugural info night.

Since 1974, every mayor has been Black. Business boomed and suburbs steamrolled the countryside. Railroading begat logistics and telecommunications: Delta, UPS, IBM, AT&T. Olympic fireworks bedazzled downtown in the ’90s, while hip-hop rooted and flourished on the city’s south side, and propagated across continents. The airport ballooned into the busiest in the world. Tyler Perry redeveloped a military base into one of the largest movie studios in America. By the 2010s, the general American pattern of white supremacy looked almost upside down in Atlanta.

But in 2020, after a century of technocracy, the City Too Busy to Hate finally cracked. Two days after Rayshard Brooks died, a reporter asked Mayor Bottoms how she felt “as a mother” about Brooks’s death. She bit her lip, lamented the killing, ventriloquized Brooks’s final thoughts about his daughter’s upcoming birthday, announced the creation of a task force, and censured the angry mob who had torched the Wendy’s to the ground. (It had existed in a food desert, she said, and “a place where somebody can go and get a salad is now gone.”) The police chief resigned. One of the officers involved in the shooting was suspended for investigation. The other cop, who shot four times, was fired and charged with felony murder—a rare indictment, indicative of emergency.

Or was it? In a city so restlessly forward-moving, it’s hard to tell sometimes what’s truly new and what’s business as usual. General Sherman burned the city to the ground, and Atlanta has spent the century and a half since the Civil War reenacting this founding trauma. Its motto is Resurgens, its mascot the phoenix, ever resurrecting from the ash heap of history. Every city booster’s plan to make Atlanta more modern, international, or cosmopolitan has been carried out by a wrecking crew, enforcing a disorienting amnesia on its residents.

Last year, all charges against the officers were dismissed, and both were reinstated to the department with back pay. Three protesters identified by police on social media from the night the Wendy’s burned were arrested and indicted with conspiracy to commit arson. Determined to somersault out of 2020 upright and armored, the city began to stabilize. The solution, as ever: demolish and build. The bulldozers aimed for the forest.

* * *

WE SURPRISE OURSELF by coming back to the forest again and again in the summer of 2021, both for scheduled activities and impromptu pleasures. Princess Mononoke is only one event on the calendar that first week of action, which is jam-packed to bring as many curious people into the forest as possible. A poetry reading in the living room, a protest downtown, a teach-in in the parking lot. We take a nap in someone’s hammock, loblollies dancing overhead in the breeze. Perhaps it is simply a relief to be meeting strangers after a year of social distancing. But we like them, these people coming together to oppose the policification of the planet—and besides, it’s also something else, something bracing, immediate, addictive splashing into consciousness, like a rush to the head of a life at last worth living, we realize on the week’s final evening at a muddy party on the bank of Intrenchment Creek.

It is a full moon, silvery and damp. A rickety plank spans the creek on tread-worn tires, and feeling brave from the music we teeter over the property line. The woods look the same, but maybe something shifts in us, because we wake up after the week of action to another Atlanta, opening up anew. For the first time in our life, we are interested in plant identification. We check out a field guide from the library and start to notice the mosaic of the life of the world, like the barn owl perched on our neighbor’s roof, or the Persian silk tree sunning prettily pink in our neighborhood park, or the different mites and gnats on our porch and the bats that eat them at dusk. “We live in the ‘city in a forest,’” says almost every zine we collect this summer—and for the first time we begin to realize this is true and even good.

The forest defenders range from freaky to basically normal. Musicians, carpenters, baristas, bohemians, skaters, punks, special-ed teachers: they are city slickers mostly, all locals. Some are ideologues: socialists, communists, autonomists, a single Young Democrat, defensive until she disappears. Others are artists, utopians, weirdos, unbrainwashed by the world but unhappy with it too. They speak in extremes: police abolition, death cult of capitalism, eat the rich with Veganaise. The forecast of climate apocalypse has given us pretraumatic stress disorder, they smirk, totally serious, with a cheeky, black-pilled grief. Most are white. Many are trans. Almost everyone is between 20 and 35. A Baptist minister invites us to organizing meetings, and, intrigued and flattered and inspired, we start to show up.

In a city so restlessly forward-moving, it’s hard to tell sometimes what’s truly new and what’s business as usual.

Depending on the group, meetings are more or less open, more or less formal. In big and serious meetings, someone volunteers to facilitate, which means keeping track of the stack of hands who want to speak and remaining impassive. Some meetings have timekeepers, some have notetakers. Others are ad hoc: “Shit, what’s for dinner tonight?” “Pizza again?” “Is the vegan place still open?” Over the next few months, working groups come together, meeting in the forest, but also in air-conditioned houses. Threads proliferate on Signal. We join a chat for the media team. Our phone buzzes all summer. We mostly only lurk, but find it’s fun to brainstorm how to spread the story about Cop City.

The anarchist internet has been on the scoop since the initial info night. It’s Going Down has been exulting over sabotaged construction equipment, exalting the black bloc for smashing the windows of the Atlanta Police Foundation headquarters downtown, exhorting readers to take autonomous action against Cop City’s corporate sponsors. The photos of burning bulldozers also give us that illicit little thrill, but our angle this summer is gentler. Somehow we want to defibrillate liberals into conscience and action. Not everyone in the media group agrees that the liberal establishment, Democratic machine, or NGO-industrial complex can help us stop Cop City, but we all know that no news is bad news. The problem is that the Atlanta Journal-Constitution is owned by major donors to the police foundation, which ensures that the mainstream coverage is bad news, too.

Our group is not very formal. Someone suggests inviting Fred Moten or Ruth Wilson Gilmore or Angela Davis to speak, and we resolve to send an email. The construction companies seem easier to sway than city government. Should we write an open letter? Organize a mass call-in campaign? Get a group together to pay some project manager a personal visit? What about some kind of spectacle? Conversation unspools. The media group starts to look like an action group. “You know those giant dancing tube men? We can get some and paint them into trees, and plug them in outside City Hall when they meet next month, and turn the power on and off so the trees keep falling down.”

“One of the figures should be a cop with an axe! He can go up when the trees go down.”

“What if instead we do it right outside the mayor’s house, first thing in the morning.”

“It would be so easy. Go to any car dealership at night.” Quickly we realize how willing some of our new friends are to violate the rules of polite society. Once we know where to look, it is obvious there are smaller, tighter-knit, quieter groups planning actions of their own. But the movement is decentralized, which means there are layers of secrecy we don’t need to unpeel—and explains why two months later we learn there’s been another media group this whole time.

“Just get two people together to do one thing,” the forest defenders like to say, “and you are also an organizer.” So we do. We don’t have many nature skills yet, but we know how to talk about books, so we Photoshop a flyer advertising a book club we want to host in the forest starting in September, to read Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order by Stuart Hall and four graduate students. We type our event into the shared calendar on defendtheatlantaforest.org. “Meet in the gazebo,” we write. “Read the intro and chapter one.”

* * *

ON A TUESDAY in early September, the city council hosts a public meeting over Zoom where Atlantans speak on the record for seventeen hours. At least two-thirds object to the police academy plans. Neighbors hate the snap-crackle-pop of gunshots from the firing range the APF has already built on the property, and just imagine how much louder and more frequent this will be when the police move the whole arsenal over. A public school teacher asks why the police department let their last training center collapse. What are their priorities? DSA members pose the decision as an existential question, not only for Atlanta, but for America. The old ultimatum of socialism or barbarism has been reframed by young organizers as care or cops. They accuse the city council of divesting from public services, sowing poverty and desperation, and then swelling the ranks of the police to keep it under control.

The following day, the city council votes ten to four to approve the lease of the land to the Atlanta Police Foundation anyway. The mayor makes a statement: It “will give us physical space to ensure that our officers and firefighters are receiving 21st-century training, rooted in respect and regard for the communities they serve.” We blink past the obvious hypocrisy, drawn instead to that watchword training, deceptively neutral, the ostensible justification of a million liberal reforms, because who could argue against training? The police after all are like dogs: best when they obey. But obey what?

“Just get two people together to do one thing,” the forest defenders like to say, “and you are also an organizer.” So we do.

On Thursday, the night after the city council vote, a large group has a bonfire in the ruin of the old prison farm. Like forty people, smoking cigarettes and feeling cynical, even if the hard-liners never believed in the power of public testimony anyway. We pass around pieces of paper, write down our hopes and desires and dreams, and throw them in the fire, which helps, even if it’s corny, and we are feeling less dispirited, buoyed by solidarity, when around 10 PM two cops walk into the forest. They order the group to disperse, hands on their guns on their hips, obviously terrified, not expecting the group in the woods to be this big or hostile. Raised voices, tense standoff, but reason prevails, and the forest defenders parade from the woods, outnumbering and outflanking the cops, who walk backward, escorting them out. The forest defenders chant: “Cop City will never be built!” “No justice, no peace!” “No forest, no seeds!” “Not one tree!” “Fuck twelve!” “We’ll be back!”

The gazebo in the Intrenchment Creek Park parking lot is by now the public forum of the forest, with protest flyers and pamphlets and zines weighed down by rocks on a picnic table, a bulletin board for announcements, surplus granola bars spilling onto the floor, free clothes hanging on a rack or rumpled in the dust, and endless cans of Dr. Priestley’s Fizzy Water, the leftover product from some failed start-up people keep carting into the forest from stockpiles all around the city. On the day of our first reading group meeting, we turn up with a thermos of hot cider and a manila folder of photocopies of the first few chapters. We’ll meet a few times over the fall, a group of around eight. Not everyone comes prepared every week so we often read whole passages out loud.

Policing the Crisis is about the fundamental transformation of the role of the police in British society during an era marked by economic downturn, immigration, racism, and moral panics about crime. No longer a “peace-keeper” but a “crime-fighter,” the new kind of cop cruises into his precinct from the suburbs, technologically enhanced, car-bound, and constantly in touch with central command. “With an emphasis on preparedness, swiftness and mobility, their behavior had something of the military style and philosophy about it,” the authors write—in 1978. They’re talking about radios.

Our study group makes a list of police technologies that might cause Stuart Hall to un-die if he learned the Atlanta Police Department uses them every day. Georgia law enforcement agencies have more than two dozen mine-resistant ambush-protected vehicles, for example. Also: surveillance cameras, license plate readers, algorithms that predict which people and places are more likely criminal, so police know where to patrol with extra arms and heightened nerves. We learn that the Atlanta police channel surf through the most surveillance devices per capita of any city in the country, 16,000 public and private cameras interlinked through a program called Operation Shield.

We bring printouts to spread on the picnic table: the police foundation website, city press releases, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Though Atlanta is the eighth-largest metro area in the country, its police foundation is the second largest, smaller only than New York’s. Dave Wilkinson, its president and CEO, spent twenty-two years in the Secret Service, was personally responsible for protecting Presidents Clinton and W. Bush, and might be the highest-paid cop in the country. In 2020, he made $407,500 plus five figures in bonuses—more than twice as much as the director of the FBI. Wilkinson lives in a small town outside Atlanta, although, to be fair, three-quarters of city cops live outside city limits too.

We hear the list of major corporations in Atlanta whose executives sit on the board of the APF so often we accidentally memorize it: Delta, Home Depot, McKesson, J. P. Morgan, Wells Fargo, UPS, Chick-fil-A, Equifax, Cushman & Wakefield, Accenture, Georgia Pacific, disappointingly Waffle House, unsurprisingly Coca-Cola—though in October, news breaks that Color Of Change, a national racial justice organization, has successfully pressured Coca-Cola off the APF board. This feels huge! Coca-Cola and Atlanta are conjoined twins, and where one goes, so goes the other. Public pressure is mounting, people keep saying to each other in the forest. We even hear people say they believe that we will win.

* * *

TWO YEARS BEFORE the mayor announced the plan for the police training center to the public, the Atlanta Police Foundation posted a video to YouTube taking the viewer on a tour of a digital rendering of their purest vision of the facility. Jungle drums echo over action-trailer strings as the camera swoops and zooms through surface parking, modernist buildings, trees perfectly topiaried. An “institute,” an “amphitheater” (folding chairs on a lawn), a “training field” with dark figures in phalanxes. Creepy 3D people jog in place through “green space,” on concrete trails flanked by soft grasses the police must plan to plant, because the forest we are coming to know has no such harmless shrubbery.

At the center of the video, and of the APF’s marketing campaign, is the “mock city for real-world training.” The video gives us one cursory shot of a block with an apartment building, a gas station, and what looks like a nightclub? A synagogue? The streetscape swarms with squad cars, paddy wagons, armored trucks, dozens of officers in bulletproof outfits. What criminal violence or public disorder brought the whole counterinsurgency here? As the camera closes in on the proleptic crime scene, we fade to another shot, where the fire department trains on specialty buildings that catch fire but never burn down.

Images like this—doctored, distorted, ideological—can make it hard to see the forest for your screen. Princess Mononoke is not the only fantasy projected onto this forest. Just across Constitution Road, Blackhall Studios speculated, leveraged, and wedged its way to big box office returns: in its four years under Millsap, the studio filmed the fourth Jumanji, the eighth Spider-Man, the thirty-fifth licensed Godzilla, and Jungle Cruise, the eleventh movie adapted from a Disneyland theme park ride.

The old ultimatum of socialism or barbarism has been reframed by young organizers as care or cops.

“Atlanta is really hot in the summer, and the light in Georgia is very toppy,” the cinematographer of Jungle Cruise told a film website. “It was very hard to control. But we had the budget where we could actually do our own sun, make it cloudy or darker if we needed.” So Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, pursued by cartoon conquistadors, quests for the medicine tree as the CGI jungle blossoms with fluorescent lianas. Green screen or “green space”—the glory of creation leaves nothing to chance. And on the far side of the forest, the Atlanta Police Foundation also dreams of total control. Their stage-set city with no shadows will be a laboratory of techniques to menace the metro area. The cops and the celebs each plan to clear-cut the forest for a grid of soundproof boxes, privatized and predictable, where they will drill lines. In the perfect model city, there is action but no crime.

Offscreen, the movie studio and police academy are related through the structure of gentrification. As Hollywood colonizes Atlanta, so too come the techies, New American bistros, luxury condos in low-income neighborhoods, and inevitably cops to clean up the streets, lest the new residents become uncomfy walking past poverty. Their visions are linked at the level of family-friendly fantasy: both condescend to a public desperate and willing to believe in the ongoing triumph of good over evil while they kick back, safely paying for streaming in their houses. There is no death on these screens—only justice. Even inconvenience is merely temporary fuel for plot. If you’re interrupted while streaming the comic, supernatural adventure of life, an army is one 911 call away to disappear your neighbors.

In 2021, Millsap sold Blackhall Studios to a hedge fund, which changed its name to Shadowbox Studios and invited other investors on board. Five hundred million dollars later, they were joined by a private equity firm that owns a large stake of the military-industrial division of Motorola—which manufactures the shiny, high-tech, tax-deductible cameras the Atlanta Police Foundation bought for Operation Shield. The arcane structure of the land-swap deal with DeKalb County allows Millsap to still claim to own forty acres of Intrenchment Creek Park, including the parking lot, though it’s unclear what he plans to do with it, because he signed a noncompete clause stating he can no longer make movies near the forest. Still, sometimes he hires crews to put up barricades and NO TRESPASSING signs, which makes him an object of pointed hate among the forest defenders, who use his name as a curse word. Ryan Millsap the rapacious, the capitalist, the vampire—Ryan Millsap, always both first and last name, destroying the wild life of the forest to distill it into money. On a metal power box by the train tracks, chunky cursive spray paint reads RYAN MILLSAP IS HUNTING ME FOR SPORT.

* * *

THERE’S ANOTHER WEEK of action in October. One morning before decentralized autonomous yoga, we show a colleague the far side of the forest, and follow the trail down to the ruins of the prison farm. We point out the crumbling walls of the cannery, overgrown by greenery. A rusted metal bunk bed twists into vision through the thicket. But is that a tent? We are surprised to find people camping outside the living room. Around the dilapidated barracks, eight or nine people with bleach-dyed tank tops, frazzled bangs, tattoos, and piercings are clumped in little groups with big backpacks, their sun-worn tents scattered through the trees.

This is our first glimpse of the outside agitators. They’re nice. They share a bathroom trench and a supply table piled with paracord and batteries and Band-Aids and a cardboard chessboard and stay up late talking about Rojava or ego death or why they went vegan or how to spit-roast a squirrel. They swap stories about running from freight police, make plans to forage food from the dumpster behind Kroger, listen to techno and hardcore from the speakers on their cracked iPhones. At least three have Crass tattoos. Some know one another from Line 3. They are all great at camping: we watch one tie a ridgeline between two trees, unfold a tarp, and all of a sudden there’s a dry bright-blue triangle where the group keeps their generator and valuables.

Their visions are linked at the level of family-friendly fantasy: both condescend to a public desperate and willing to believe in the ongoing triumph of good over evil while they kick back, safely paying for streaming in their houses.

Roaming solo with our camera one morning, we run into Eliza on a walk with two people from out of town. Eliza is a lyric poet and self-inflicted revolutionary, blazing nobly through a world clarified by their confidence. They have spent time among the Zapatistas. It was Eliza’s idea to throw our dreams into the bonfire last month, so they might be purified by the flames. They moved to Atlanta in 2019 because it was cheaper than Seattle, and they had friends who had friends here squatting, making music, community gardening, cooking with Food Not Bombs, producing freaky circuses, and interlocking in complicated polycules in a DIY anarchist scene on the east side of the city. We see Eliza in the forest all the time. They wait tables at a Mexican restaurant and bring leftovers to meetings, where they are unfailingly optimistic, eyes on the prize of utopia. We’ve also seen them whispering a few times with wolf-eyed punks we don’t know, and this sighting further confirms that Eliza is close to the center of the decentralization.

We see them before they see us. We wave, and Eliza beams at us, and the outsiders, grainy in the morning mist, clam up immediately. They eye our camera with suspicious contempt. We say, “Hey.” Eliza tells them they trust us. So one says, “I’m Meadow.” The other says, “Gout.”

“Nice knuckle tats,” we say, icebreaking. Gout’s fingers read WEVE LOST.

“Thanks.” Meadow and Gout are here from Appalachia, where they’ve been involved in a struggle over a pipeline, and it’s nice to be in a different forest, warmer down south, new birds and bugs, but also confusing. Back at the pipeline there are movement elders and formal initiations, and the direct actions there are nonviolent and planned in advance, whereas here in Atlanta . . . the two make eye contact. Gout shrugs. “Anything goes.”

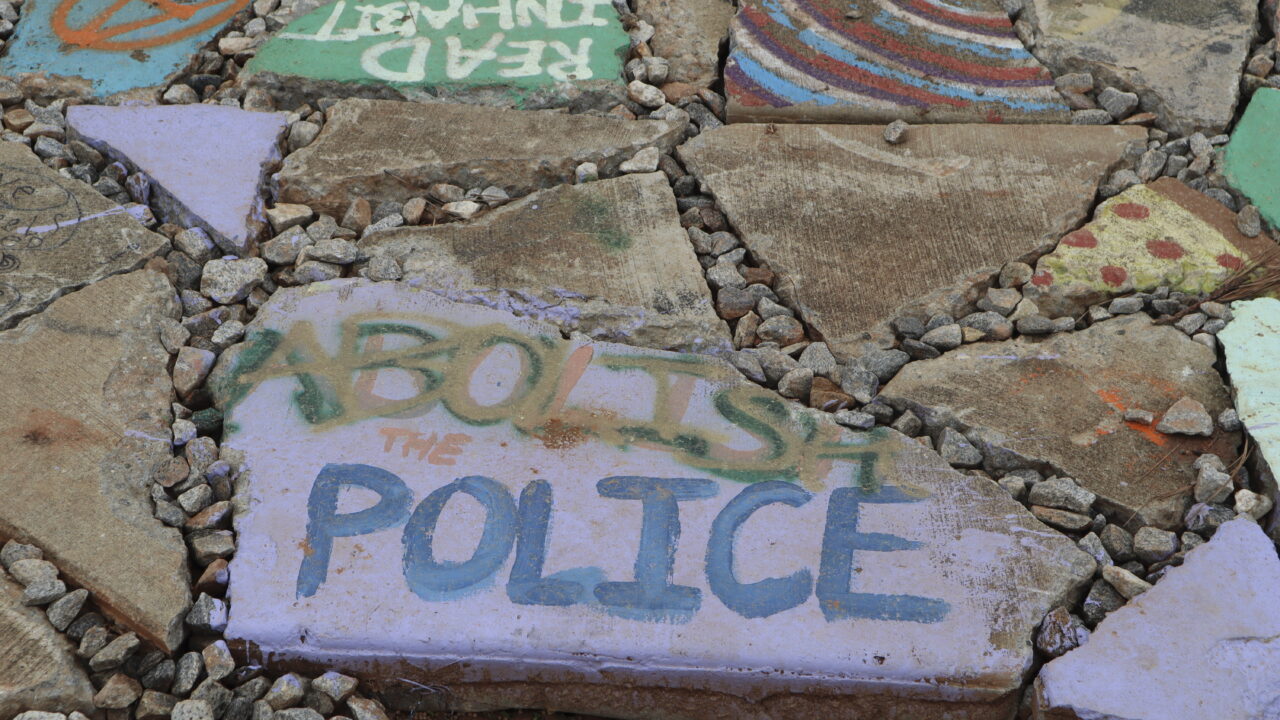

The week of action ends more or less without incident, only this time not everyone leaves the forest. A small group settles semipermanently in the living room, sleeping in tents, cooking on a Coleman burner in a Goodwill pot. We will never see the living room empty again. Chairs appear around the firepit. License plates in the parking lot from Virginia, Michigan, Quebec. STOP COP CITY graffiti goes up around Atlanta.

At the end of October 2021, the Atlanta Police Foundation pledges to heed community input and redesign the training center. They downgrade the “mock city” to a “mock village.”

* * *

WINTER FALLS. It barely ever snows in Atlanta, but the nights get long and cold. The loblollies stay evergreen, but the oaks lose their leaves, and the shrubby understory dies back to brown and gray. You can see farther in the forest in the winter. It is easier to walk. No snowmelt means the ground is rarely muddy, so everything crunches dry and friable underfoot when we follow the ecologist down the hill from the living room, right at the fork, left at the next, to the mother tree, or grandmother tree, some people say instead, a cherrybark oak ten feet wide at its base and swaying stately up into the thin green canopy.

A forest defender in a long lace dress and combat boots is sweeping the leaves from the clearing with a broom handmade from a branch and spindly twigs and retted forest fiber.

A forest defender in a long lace dress and combat boots is sweeping the leaves from the clearing with a broom handmade from a branch and spindly twigs and retted forest fiber. She takes care not to disturb the offerings people have started leaving nestled into the mother tree’s roots, spilling out onto the brown ground: knitting needles, Buddha candles, jack-o’-lanterns, giant pinecones, some long-dead stag skull, its cranial sutures curling like mountain roads. A magpie flits to the ground to peck at a pineapple in the altar when it thinks she isn’t looking. Chipmunks chitter, plump for the winter. A wind rustles the mother tree and more leaves fall.

And yet. The police foundation has recently issued a press release claiming that this land is not a forest at all. The “growth” consigned to be bulldozed, they say, “should not be described as mature.” The land is “marked by little tree cover,” and is populated by “largely invasive species of plants and trees that have sprouted over a twenty-year period.” The ecologist leads us across a skinny, sturdy plywood bridge strapped to empty plastic carboys floating on Intrenchment Creek, so it rises and falls with the tide. He crushes a bulb between his fingers, sniffs it, pokes a stick into the soil, churns up a pool of groundwater. This place, he says, has been disturbed.

This is a technical term. A disturbance is a sudden exogenous shift in a relatively stable ecosystem, as by flood or fire or locust or fleet of angry chain saws. But crops are even more stable than forests, so abandoning agricultural land constitutes yet another disturbance, says the ecologist, gesturing around to the aftermath of the prison farm fields. Disturbance ecologies are wild and weird places. Imbalanced species compete in volatile dynamics. “How many times has the land been disturbed?” we ask, afraid of the answer.

Most Indigenous agriculture happened closer to the floodplains, the ecologist explains, so the Muscogee likely used these woods for hunting. But the settlers definitely logged. He examines the underside of some leaves. Seems likely the land was in cotton before the boll weevil blight in the 1920s. Then of course there was the prison farm. After which the loblollies colonized the property. They are shading the soil to refresh it, so that stronger trees might grow back later. It is a young forest, diagnoses the ecologist. A promise of a forest in the future.

For now, the ground is covered in Japanese stiltgrass and scraggly privet, which the ecologist pulls up in clumps as we walk down a trail deeper into the woods. It wants a controlled burn, he says, to kill these invasive species so the forest can mature into a healthy adolescence. It is hard for us to imagine controlling a burn; it sounds like controlling a bulldozer. Shouldn’t life run wild and free to reproduce as it pleases? The trail meanders down a declivity into a grove, where mossy, weatherworn marble blocks lie scattered in the shade. What is the capital of this Ionic column doing in the forest? The ecologist doesn’t know either. We crouch to brush the privet off a complicated carving. Elegantly chiseled into the center is the name VIRGIL.

Huh? Clearly there’s still so much about this forest we don’t understand. We’ve heard the Atlanta zoo once buried an elephant here—or was it a gorilla? A giraffe? Is it true that Civil War soldiers shot at one another through these trees? We walk along the bank of a pond, which someone once told us the prison farm wardens flushed with arsenic to delouse the dairy cows. The prisoners who died of arsenic poisoning were buried unmarked in these woods. But where? Nobody seems to have all the answers.

The prisoners who died of arsenic poisoning were buried unmarked in these woods. But where?

The forest defenders say that white supremacy and settler-colonialism have cursed this place, and the only solution is simple: give the land back. They’ve started calling the forest Weelaunee, after the Muscogee name for the South River—even though the South River does not run through either of the properties at risk. At some point, the name must have gotten mixed up with the civic proposal for the South River Forest, because the forest defenders, and soon the publications quoting them, have all begun to say or imply that this land has been called the Weelaunee Forest since time immemorial. Sometimes Weelaunee refers to the territory held stubbornly by the movement against the developers. At other times, it seems boundless, mythical, and much bigger than Atlanta.

We want the documents. We make an appointment at the Atlanta History Center, which means we have to drive to Buckhead, past tacky landscaped mansions and Brian Kemp campaign signs. As we work our way patiently through boxes and folders of pencil-kept files, a narrative starts to take vague shape. It is riddled with inconsistencies, decades-long silences, and is maddening to try to keep straight. Half the official Atlanta historians and land-use consultants confuse the city prison farm with the nearby, similar, but definitely distinct federal prison farm also harrowing the city outskirts. The files in these boxes make references to paperwork at medical and psychiatric facilities whose archives are kept elsewhere. If at all.

* * *

THE PRISON FARM was founded in 1922, when the city council rewrote a zoning law in order to build a city prison outside city limits. Free forced prison work solved the problem of the labor shortage at the city dairy farm, which had been founded recently on land Atlanta bought from the Keys of Key Road. The Key family had owned and used this land as a slave plantation since 1827 and been enriched into minor city elites. A census at the outset of the Civil War shows nineteen nameless people as George Key’s personal property. We know almost nothing else about this period. The records have disappeared.

In 1939, city council meeting minutes called the prison farm an economic success, and Atlanta resolved to purchase the property on the other side of Intrenchment Creek to expand the promising prison farm beyond the boundaries of the former plantation. In 1953, the Atlanta Journal sent a photographer to the prison farm. An image shows five prisoners in the shade of an oak reading the Atlanta Journal. The men face away, expressions obscure: mixed-race, wearing undershirts, two on a bench, three sprawled in the grass. One takes a nap with a paper on his face. There are no fences in sight.

In 1965, on a tip from a desperate inmate, the Atlanta Constitution sent an undercover journalist to report from inside the prison farm. From the bunkhouse, Dick Hebert described drug smuggling, gambling rings, alcoholism, contraband coffee, bribery, bedbugs, boredom, and terrible food. He cut kudzu on the side of the highway. The other prisoners wandered away unsupervised to recycle glass bottles into pocket change for booze and returned to the chain gang, Hebert was astonished to report, because there would still be a bed and more booze at the prison farm tomorrow. He did not see or mention the farm work.

Four years later, the prisoners went on strike. In May 1969, they stopped work over the food, the indignity of being forced to work for free as office lackeys for the Atlanta Police Department, and the same old catch-and-release cycle: dropped off uptown late at night with nowhere to go and rearrested in the morning for sleeping outside. In July, they went on strike again. Bill Swann, an ex-mechanic who had been in and out of the prison dozens of times within the past year, spoke to the Atlanta Constitution on behalf of the strike. “This is a peaceful, nonviolent protest. But I ain’t saying there aren’t some who want to tear things up. I’ve been walking around from bunk to bunk to try to keep things like that from happening.”

Eight years later, the downtown central library was demolished. Andrew Carnegie had donated the building to the city out of Gilded Age beneficence, but the homegrown capital of the New South no longer needed philanthropists patronizing from the North. To clear the block for a brutalist box, the marble facade of the neoclassical library was dismantled stone by chiseled stone. VIRGIL ended up dumped on the prison farm site alongside HOMER, AESOP, DANTE, POE, MILTON, thousands of tires, mounds of household garbage, and other hazardous material the city didn’t know what to do with.

How is it possible no city documents commemorate exactly when the prison farm closed?

The prison was already shrinking, on its way to an inevitable closure. After federal court–ordered desegregation, after years of prisoner strikes against recrudescent conditions, after round after round of reforms implemented at great cost—new dormitories, better meals, new infirmary, new fences—the farm hit diminishing returns. Mechanical agriculture consolidated in the distance, and even prison slavery couldn’t compete. Throughout the 1980s, the farm was scaled back down to dairy and livestock—250 cows, 300 hogs, 145 prisoners—and abandoned field by field.

Another group of newspaper photos in the second half of the decade shows Black men hosing down a concrete cell of piglets, staring out a blurry window, and exiting an empty classroom. On the board in white chalk is a crowd of naked torsos, ambiguously gendered, ambiguously human, a skeleton hand hovering, a field of cartoon jugs of liquor labeled XXX receding into the distance, and a micro-manifesto:

DYING

FOR

A

DRINK

??

How is it possible no city documents commemorate exactly when the prison farm closed? Sometime in the early 1990s it was open, and then it wasn’t. The silence makes us shudder. In our less materialist moments, we can sense some telluric, demonic force, older even than money, seething through the archive. The plantation, the prison farm, the police academy: it sounds like a history of America. Is this not one symmetry too many to be a simple coincidence?

* * *

AND THE PINES REGREW over the prison farm. With them came pecan, persimmon, muscadine, yarrow, vetch, privet, greenbrier, sorghum, hackberry, dewberry, wood fern, Bradford pear, honeysuckle, iris, so many mushrooms, tufted titmice, white-tailed deer, little turtles, rat snakes, butterflies, woodpeckers, wrens, and earthworms squirming through the loamy soil. Some of these plants never left but grew back. Others grew here anew. The vetch and sorghum were likely planted by the prison farm, holding on now to the fledgling forest in its afterlife.

Time passed. Intrenchment Creek Park was founded in 2004, underwritten by the charitable foundation of Arthur M. Blank, a Home Depot cofounder and the owner of the Atlanta Falcons. The prison farm site stayed off-limits, though only on paper. Soon its mongrel ecosystem also harbored mountain bikers, RC pilots, teenage lovers, the homeless, joggers, dog walkers, bird-watchers, and amateur archaeologists seeking respite, pleasure, and adventure away from traffic and taxes. Every few years the prison farm ruins would spontaneously combust. In 2009, the fire department scolded homeless squatters. In 2014, when it happened again, the perplexed fire chief said to the local news, “I don’t know how much more you can burn an old prison down between the walls and the bars.” In 2017, an enormous tire fire took eighteen hours to put out. You could see it from planes taking off and landing at the world’s busiest airport just across town.

* * *

THE FIRST FOUR ARRESTS take place in January 2022. Instagram said the event would be “fun and friendly”: breakfast, banner-making, kids, for some reason a march through the woods. OK. We follow the crowd. On the west side of the creek, the protesters play telephone in between chants. “Misdemeanor trespassing,” someone turns around and says to us intently. “Pass it on.” So we turn around and say it the same way to the next person in line.

Neon-vested workers appear through the trees, drilling into the ground—taking soil samples? Suddenly there’s shouting at the front, a line of masked people surrounding the workers, and then, from nowhere, cops surrounding the march, a warning on a megaphone—a kettle in the trees! Now everyone’s shouting. We look around for eye contact with our friends, and just as suddenly the line breaks and people scatter in all directions. Fugitively, ridiculously, we fly through the foliage, cursing our hi-vis purple coat, until we crash through the brush out onto Key Road and into the suburbs beyond, slowing our breath and our gait, nothing to see, another pedestrian on an innocent walk. A knight in a shining station wagon glides up the street. “Do you need an evac?” Blue lights flash as we wheel past the parking lot. A hooded figure is being led out of the forest in handcuffs.

“I don’t know how much more you can burn an old prison down between the walls and the bars.”

Instagram roils with outrage, told-you-so, and recommitment. As winter thaws, new people keep coming to the woods to check out the hubbub firsthand—and to live deliberately, in self-sufficient solidarity against the state and its forces of plunder. Soon, half of the people in the forest are trans. It is less white but only slightly. Crustpunks and oogles take the freight train into town and say things like “DIY HRT.” Forest names are by now common practice, both for security purposes, because who knows who might be listening, and out of a common sensibility slightly more serious than play. By spring, there’s a new cast of characters in Weelaunee: Blackbird, Dandelion, Hawthorn, Shotgun, Squirtle, Gumption, Wish, living on dumpstered or bulk-bought food, tentatively cosplaying the other possible world. Someone calls it Season Two. We watch one teenager recruit another to the unfolding miracle, the invasion of an alternative into reality. “Life in the forest is awesome!” she shouts, barefoot in the mud. “No rent, no parents!” Once the first treehouse goes up, it’s only a matter of time before the whole forest is building treehouses.

They work mostly in teams of three: two above, harnessed, nimble, feet in the crotches of branches, one below, tying tools to the end of a rope to be hoisted plumb up into the canopy. It is hard to see unless you’re right underneath, because the forest defenders have also settled on a uniform: camouflage and balaclavas, like tropical guerrillas. Online, this is widely interpreted as a signifier of the movement’s militancy. But when we ask Eliza, they tell us it’s primarily an anonymity measure, because people are camped on the far side of the creek, which is technically trespassing. This is the same reason the anarchists turn off their phones and leave them in a bag a hundred feet away before meetings, even if all they need to meet about is whether the floor joist of this treehouse should be a catwalk or a traverse.

In April we meet Magnolia, in their characteristically sensible tank top and ponytail and glasses, who is building a kitchen in the woods. Magnolia is a practical person. Patient and gentle and modest until you get in the way of their work, at which point you get pulled aside for a meeting about how we can work together better. Instagram has advertised another week of action—the third and biggest yet. All hands are on deck. Everyone knows someone coming from out of town, and no one knows how many people to expect. We invite an anarchish friend from Philadelphia to sleep on our couch, and not two hours later, someone we forgot from college texts to say they invited themself from online and are planning to show up with an even stranger stranger.

Magnolia moved directly from college to the forest. They have been cooking in the living room for months, mostly basic sustenance to keep the campers happy, but also for big events, which are happening increasingly often as the movement agglomerates allies. Even more than the police, Magnolia knows, the enemy is hunger. Back in November 2021, when a Muscogee delegation came to do a stomp dance—the first ceremonial return to this land since walking the Trail of Tears, we heard—the forest cooks made mashed potatoes and nine vegan pies and wild rice with black Weelaunee walnuts, and stew from a frozen roadkill deer, which took too long to thaw, so Magnolia had to hack it into pieces with a pickax. “How long has it been since these trees heard our language?” asked the Mekko to nodding allies. After the ceremony, the Muscogee dancers turned out to have already eaten, so the forest defenders ate venison like kings all week.

But the week of action slated for mid-May 2022 is bigger than even Magnolia can handle. They call up a traveling trio of cooks they met at a land defense struggle out west a year earlier, movement veterans who have catered all the major environmental activist summits since the ’90s, and ask them to help. Now it is merely a matter of building a kitchen to make the lunch ladies proud. Magnolia and their partner choose a spot five minutes from the living room, close but far enough away, and borrow and bargain and reroute donations toward coolers and ten-gallon pots, propane and burners, cutting boards, can openers, a five-hundred-foot hose. Various infrastructuralists lift milk crates from the streets, scavenge metal shelves and armchairs from the junkyard, dig poop trenches, cut the privet and kudzu back to widen the path to the living room. Someone rigs up a camouflage tarp over the kitchen so you can’t see it from above or even thirty feet away. During the work, someone else names the new kitchen Space Camp, and it sticks.

On the first morning of the week of action, Eliza wakes in the living room to clamor and panic. “Cops in the forest!” They unzip the tent, strangely calm, and listen to the ambient gossip. A bulldozer has just barged into the forest and the activists are already cursing out Ryan Millsap. By instinct or hive mind, campers swarmed the machine throwing rocks, and Eliza arrives during a cinematic standoff in the RC field, yellow machine alone against giant blue sky. Every inch the bulldozer gains is met with a rain of rocks. Four cop cars arrive with sirens and the officers stand on either side of the bulldozer, preparing to pepper spray, when from the trees some thirty people in camouflage emerge and march in a line on the cops, chanting “Move back! Move back!” as if they are the cops! The squad cars peel away in fear and the bulldozer lumbers back, rocks pinging off its back grille. The forest defenders exult as the camo bloc deliquesces into the trees.

We look around for eye contact with our friends, and just as suddenly the line breaks and people scatter in all directions.

Someone has built a suspension bridge across Intrenchment Creek, a genuinely beautiful piece of engineering, strong and springy, made from supple softwood and steel wire. There’s a big camp in the living room, but also many small camps all over the forest, and though there’s a difference in activist cultures on either side of the property line—public/trespassing, hippie/anarchist, peaceful/militant—people use the bridge to bounce across the creek all week, so many that there’s a line built up on both sides. Waiting to go see the treehouses, a nearby forest defender in a balaclava suddenly feels woozy. Philadelphia rushes over, says I got you, opens their backpack, pulls out a Gatorade, energy bars, Advil. “CVS was giving stuff away today for free.”

So much else happens this week: art builds, movie screenings, public marches, Shabbat dinner, a foraging walk for a wild psychedelic mushroom only found in North Georgia, a puppet show in which Joe Biden is incarcerated in Plato’s cave. An upside-down black sedan appears overnight in the entrance to the power line cut. A delegation comes from Standing Rock carrying a sacred fire. The forest defenders pledge not to let it extinguish, and spend the week taking shifts tending the fire in a clearing between the kitchen and the living room, singing corny country on the guitar and organizing expeditions to gather firewood. We spend two afternoons this week chopping cabbage and stirring onions downhill in the kitchen for the rolling buffet of rice and vegan beans and low-FODMAP slaw. Insiders and newcomers wander in and out, washing their hands in these magic hydraulic sinks someone’s contrapted out of two plastic buckets and a foot pump, drying dishes with donated T-shirts because we ran out of rags on day three, mashing chickpeas with the bottom of a mason jar, sweat glistening down spines, adjusting salt until everything’s too salty, making the same lewd joke about Mayor Dickens succeeding Mayor Bottoms.

By now the Atlanta Police Foundation has announced the training center is on track to open in fall 2023. For months, forest defenders have been targeting Reeves Young, the Atlanta-based lead contractor, flooding phone lines by day and sabotaging construction equipment by night until the company backs out. During the week of action, activists march on the Atlanta headquarters of the new contractor, Brasfield & Gorrie, and vandalize their offices: graffiti, broken windows, splashes of red paint to symbolize the carnage. It’s $80,000 worth of damage, says Fox 5. The next day, other activists march through East Atlanta Village led by a delegation of preschoolers. Later in the week, yet another group marches through the city carrying branches from the forest like a punk production of Macbeth. The cops surround this group in a park, tackling activists indiscriminately, spraining someone’s wrist, squeezing zip cuffs way too tight, and arresting twelve people on charges that all get dropped.

Magnolia initially calculated needing seven hundred gallons of water to last the week of action, but we watch them watch the water flow unexpectedly fast out of the giant plastic tanks at Space Camp, increasingly nervous, until someone else approaches the kitchen with the same concern. This person and Magnolia and whoever’s nearby and interested turn off their phones and have a meeting to organize an infrastructure to run water through the woods. They designate a zone in the parking lot where campers can leave empty carboys to be filled up at people’s houses and visitors can drop off water to be hauled back to the kitchen. More than anything, Magnolia loves this task: no meetings, no conflict, no speaking, no thinking even, you just strap a jug to your back and walk through the woods.

They call this “the unfathomable bliss of being a cog in someone else’s machine.” For all the talk about autonomy, sometimes you want to be of use. Is this what’s so enlivening about the week of action? We are happy to see our friends, of course, but it’s something more, and they sense it too, a subtle reorientation of our body to other people, to abstractions like work and time. We chat while we work with young strangers, exchange biographies and motives and meanings. They mostly say they came to the forest to learn from militant struggle at the crossroads of racism, ecocide, and the forces of social control, and then laugh when we say that we’re here because we love the logistics.

But it’s true. For a few transcendent instants this week we feel like a gnat in a swarm, a spontaneous, collaborative choreography unfolding around us. Again we are exhilarated by the rush of—it’s not exactly solidarity, but something even stranger and more miraculous, closer to goodwill. There is no money in the forest. People share what they have and borrow what they don’t. Something clicks about gender and number: everyone in the forest presumes without asking that others are all they/them, because assembling here is something like a we/us, which feels both lost and found, long forgotten and newly, mawkishly recovered.

Every inch the bulldozer gains is met with a rain of rocks.

Which is of course not to say it’s all a happy trippy orgy. We notice ourself developing little resentments toward the militants in camo sitting all day by the bonfire and gloating about smashing up windows while never seeming to cook or haul or clean or help make camp. But Eliza reminds us that everyone has strengths and needs, even us. This is in fact a sign, they say, of a healthy ecology of tactics. For every militant crowing about the next direct action, a pacifist making them possible through indirect activity.

The people who came go home. Two days after the week of action ends, the police raid the forest encampment. They slash and trample tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of tents and generators and kitchen supplies, stomp out the sacred fire, cut down the suspension bridge, topple six treehouses. Eight people are arrested on charges ranging from “criminal trespass” to “obstructing law enforcement.” The Atlanta Police Department releases a video of a flaming object flying from a tree. Our mom calls to make sure we’re safe. “Aren’t you concerned about . . . law enforcement?” she wheedles, all concern. The term sounds so neutral and alien, it hardly registers what she means.

The next day, Unicorn Riot releases an audio file of radio banter among a police unit participating in the raid. One says Molotov cocktail. The next says deadly force encounter, meaning we are authorized to shoot to kill.

“Is this the uh protest against Cop City?”

“Sure is. They’re mad about a forest that they’ve never been to.”

“They probably never even knew about the forest until now too. Man that sounds like a uhhh uh scene out of Mad Max.”

“I don’t think they actually care about the forest at all. I think it’s just all about being anti-police.”

“That is a uh great movie by the way, right? Really good movie.”

“I was about to ask if you, uh, if you’d watched that flick before.”

“Believe it or not, I actually watched it when we were all on that detail at the mayor’s mom’s house. Watched it out there on my phone.”

* * *

EARLY SUMMER, 2022. On Instagram, a gallery of graffiti under highways across the country: STOP COP CITY and DEFEND ATL FOREST in Portland, Pittsburgh, New Orleans, New York, Kansas City, Tallahassee. In places like Highland, Indiana, and Erie, Pennsylvania, people smash plate glass windows at Banks of America, Wells Fargos, and the offices of Atlas, a national technology consultancy and Brasfield & Gorrie subcontractor.

Undaunted, committed, hardheaded, the forest defenders move back into the woods. Treehouses keep appearing as if the forest is a fairy-tale Levittown. They build outposts deep into APF territory, but also in the border zone by the creek, in sturdy old oaks not at risk from either Cop City or Ryan Millsap. Is this strategic? Some activists also start spiking trees, a tactic straight out of the Earth First! playbook, which involves hammering long metal rods into tree trunks at random and then posting signs all over the forest that say something like, “Don’t log here or your chain saw will blow up,” in English and Spanish.

One Friday morning in mid-July DeKalb County police officers accompany a construction crew to the parking lot, where they put up concrete barricades. Did Millsap the Rapacious ask them to do this? The county recently issued a stop-work order against him after the incident with the bulldozer. Is this legal? Does it matter? The lawsuit over the land-swap deal is ongoing and nobody knows whether the park is actually open, but the law seems less important now anyway than who is in the forest and with what force. Antlike, activists quickly lift the thousand-pound things out of the way and paint them bright colors to prepare for the fourth week of action, upcoming already. A new sign at the trailhead announces yet another name, Atlanta echoing Berkeley echoing the Cultural Revolution: WEELAUNEE PEOPLE’S PARK.

The lawsuit over the land-swap deal is ongoing and nobody knows whether the park is actually open, but the law seems less important now anyway than who is in the forest and with what force.

On the Saturday morning of the week of action, Millsap sends a man in an excavator to tear down the gazebo. Its bucket collides with the roof. The people inside throw what they can. Hummus sandwiches splatter across the windshield. Dr. Priestley’s Fizzy Water bursts on the treads like a thousand clowns’ seltzer sprinklers. The ungainly machine trudges off. The work crew leaves behind a year-old Dodge Ram. By the end of the week of action, it has been husked by flames and washed by rain and covered in symbols: the squiggly arrow for squatters’ rights, the trans circle sprouting with pluses and arrows, the uppercase Ⓐ and lowercase @, the Black Power fist, here and there a HA HA, cartoon cats, hearts, cop cars on fire, and a million graffiti flowers.

The permanent camp in the forest continues unbidden into the fall, with the constant help of a network of Atlantans hauling in water, hauling out trash, coordinating essential services with forest defenders over Signal. New, very young people arrive constantly from all over the country, some from Canada and France and Italy, because they heard on Instagram that the forest is a bulwark against the creep of fascism and it needs bodies. They spend all day hanging out at the living room campfire writing poems, eating Nutter Butters, and strumming on mandolins.

One September afternoon we are delivering ice to the forest and ask a Signal thread for help hauling it into camp. A new upright piano sits in the dented gazebo. We start up the bike path, ice dripping down our shoulder, when out of the woods walks Tortuguita carrying a cooler, smiling in the sunlight. It is hot. Big dinosaur clouds overhead. Tortuguita is jazzed, chatty, petite, as graceful as you can be carrying a cooler. We carry it together, one person per handle, and chat on our way into camp. Tortuguita just returned from a two-day intensive wilderness medic training program. They had dropped out of pre-med in Aruba. Do you still want to be a doctor? we ask. “Hell nah,” Tortuguita says, insouciant. “You have to cut out some of your empathy to be a doctor.”

A group of reinforcements comes from Albuquerque to help build infrastructure, a couple at a time, every few weeks, like little needful drops from a pipette of know-how. They build a new kitchen in the parking lot with a rainwater catchment system for the dishes and plant a vegetable garden behind it, which they fertilize with composted leftovers. Winter is coming, they say, doing math for a week to determine where the hothouse should be, at what angle its roof will trap the most sunlight, efficiently distributing tasks. They steal nails from Home Depot, ask a group of party kids from New York to pay for two-by-fours, put together a frame in a day, make a slanted roof out of corrugated plastic and walls out of shipping pallets. They stuff insulation in the gaps of the pallets and shellac to the shack a skin of political signs—Warnock, Abrams, Williams, Kemp, mostly upside-down—plucked at night from the Moreland Avenue median.

This month we also meet Pandabear, who is building a treehouse alone. Radicalized by videos of vegan street activists and bored of bouncing around upstart farming communes in the Northeast, Pandabear used his stimulus money to buy backpacking gear and walked alone down the Appalachian Trail almost directly to the forest this spring. He is gawky in an endearing way, wears camo everything: balaclava, gloves, even olive-khaki boots. He is not a skilled carpenter, but is borrowing tools and learning to build plank by scrapyard plank. He recruits us to hold a piece of particleboard in place sometimes when we pass by his construction site, in the shade of a beautiful oak on flat ground near the creek.

Temperatures drop, slowly then quickly. There are deer all over the woods this fall, more deer this year than last, which moonier forest defenders interpret as a sign of nature’s boundless abundance, overflowing with life, affirming their mission, though the deer leap away whenever humans approach. Magnolia finds two black rat snakes and names them Anti-Freeze and Slinky. Despite the new kitchen, the campers are hungry and quarreling. Eliza starts to have to act like a camp counselor, encouraging the teenagers to take some initiative and clean up after themselves. The Albuquerque builders brigade says it more bluntly: Use your autonomy or die.

Winter descends upon a discontented living room. New young people show up alone and act reckless: graffiti nearby suburbs, throw cinder blocks at passing traffic, slash the tires of the Al Jazeera rental car. Things get paranoid, almost nihilistic. Just as the governor invokes outside agitators, the forest defenders murmur about agents provocateurs, and you can tell who went to college by how they pronounce it. Pandabear must have miscalculated, because when he tries to pulley his platform up into the tree, something doesn’t fit. He gives up for a week or so, but daunted by winter, comes back to his woodpile and says OK it will be a hut.

Winter is coming, they say, doing math for a week to determine where the hothouse should be, at what angle its roof will trap the most sunlight, efficiently distributing tasks.

In early December 2022, a construction project near the forest burns down in a mysterious fire. The police have no evidence linking the forest defenders to this fire, but they raid the camp in retaliation, arresting five—this time, for the first time, on felony charges of domestic terrorism. The district attorney cites a law rewritten in 2017, after the white supremacist massacre at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, when the Georgia legislature redefined domestic terrorism as any criminal act that “is intended or reasonably likely to injure cause serious bodily harm or kill not less than ten individuals any individual or group of individuals or to disable or destroy critical infrastructure.”

War on terror tactics have become Georgia jurisprudence. The statute defines critical infrastructure as “public or private systems, functions, or assets, whether physical or virtual, vital to the security, governance, public health and safety, economy, or morale of this state.” Stuart Hall et al. echo prophetic through the treetops: “The state has won the right, and indeed inherited the duty, to move swiftly, to stamp fast and hard, to listen in, discreetly survey, saturate and swamp, charge or hold without charge, act on suspicion, hustle and shoulder, to keep society on the straight and narrow. Liberalism, that last backstop against arbitrary power, is in retreat. It is suspended. The times are exceptional. The crisis is real.” Pandabear watches from the branches of his oak, breathing as quietly as possible, as the police destroy his hut with heavy machinery down below.

The forest defenders flee. Some go back home to Knoxville or Houston. Others crash on the couch or floor of a house in the suburbs some benefactor of the movement has rented for a year. Just before Christmas, contractors hired by Millsap return to the parking lot. They jackhammer everything to smithereens: the parking lot, the trailhead, the bike path all the way up to the line where Millsap’s fiefdom apparently ends. The next day they start to fell trees, including one with a treehouse. A week too late, DeKalb County issues another stop-work order, this time for removing trees without a permit.

It is New Year’s again already when gingerly the defenders move back into the forest.

* * *

IT IS JANUARY 18, 2023, and dense with morning fog. The Atlanta Police Department, DeKalb County Sheriff’s Office, Georgia State Patrol, Georgia Bureau of Investigation, and Federal Bureau of Investigation conduct a joint “clearing operation” in the Weelaunee Forest.

Pandabear hears shots, so many shots, from up in the branches of his oak by the creek. This time, the police sweeping the forest spot him through the withered leaves. There’s a standoff for what feels like hours. Pandabear sends videos out on Signal threads. We are home, glued to the screen, whiplashed with rumors—did someone die?—all alone, when the police start shooting pepper balls into the canopy and he stops responding to texts.

Signal doesn’t know who it is either when the stories start to spread across our timeline: “First Environmental Activist Killed by Police in America.”

Eliza is pulling into the parking lot at work when they get the call from their partner. They enter the restaurant sobbing and their managers understand. They drive to someone’s house, where twenty forest defenders sit in the dark, scrolling, vacant faces glowing, silent as conversations all trail off into nothingness, taking constant smoke breaks outside where months-long grudges disappear without words.

Signal doesn’t know who it is either when the stories start to spread across our timeline: “First Environmental Activist Killed by Police in America.” This first day, the news’s only source is the GBI. No one wants to go to the forest, so there’s a vigil in Little Five Points instead, where the forest defenders, dwarfed by the enormity of the city, cry, block traffic, chant into megaphones, and huddle to keep candles lit in the rain, wondering who it was, crowdsourcing information and winnowing the list down to a few forest names. A half-hearted riot dissipates before they’ve even smashed a window. We feel hollow to watch it. We won’t feel anything until tomorrow when the media releases Tortuguita’s legal name, and even then, we don’t know who that is until someone posts a photo on Instagram.

The GBI says Tortuguita shot first but doesn’t have or won’t release the bodycam footage to prove it. An independent autopsy later says Tortuguita was seated on the ground with their hands up. They were on the public park side of the forest, not even trespassing. Fifty-seven bullet wounds. Is this a mass shooting? The exonerating injuries perforate their palms like stigmata.

By the time Democracy Now! picks up the story, Pandabear is in the intake room at DeKalb County jail. His clothes reek of pepper ball and the officers can’t stop coughing. When he finally takes a shower, the water reactivates the chemical, scorching and pouring down his body.

* * *

TURNS OUT DEATH is what it takes to break the national news. Almost even more confusing than the loss of Tortuguita is the sudden attention it brings to the movement. Congresswoman Cori Bush tweets about the killing. A professor and former president of Emory University steps down from the board of the Atlanta Police Foundation under pressure from faculty and students. Morehouse and Spelman College professors and students sign public letters to Stop Cop City. We scroll and scroll as these bastions of the Atlanta elite founder at the force of the news. National racial and social justice groups demand the resignation of Mayor Dickens, who says nothing, only breaking his public silence the following week to condemn “violence” and “property destruction” when the forest defenders regroup to take vengeance on the city.

Is the Atlanta Way finally falling apart? Does it matter? The latest round of photos of burning cop cruisers feels less exhilarating than mechanical: you strike, we strike back, you always strike back harder. The damage only ever gets worse. How many more of these cycles can we withstand? A secret, selfish thought starts to whisper through the solidarity. Do we care enough to die?

Tortuguita’s parents and brother fly to Atlanta to meet the forest defenders in an Airbnb. Their mom brings childhood photos from Panama. Eliza sits there sifting through the pictures and a life starts to take shape in time. Tortuguita had been vague to them, one of hundreds of comrades in the forest, but comradeship is impersonal. Whereas there now is tiny 2D Tortuguita cheesing for the camera at Disney World. Grief hits Eliza like a bulldozer: slowly, unstoppably, inevitably, then all at once. They shake, suppressing sobs on the couch. Tortuguita’s mom comes over to comfort Eliza, holds their hand, wiping away tears and sitting up straight, somehow, impossibly, composed. “Thank you for being there with my Manny,” she tells Eliza. “He was—they was—they is—my hero.”

Turns out death is what it takes to break the national news.

Pandabear is charged with criminal trespassing and domestic terrorism. He is the only one of the seven forest defenders arrested that day to be denied bail. At least his cellmate is chill. While his dietary form is processing, he trades packs of commissary ramen for whole trays of food with the guys in his pod, and then individual items from their trays to make himself vegan feasts. He hoards apples in his cell, works out, plays chess, talks to his mom on the pay phone every day. It is almost a relief to spend so much time away from the internet. He receives more than a hundred postcards from comrades around the country. The dietary form finally processes and procures him vegan meals until the jail hires a new food service provider that serves all the inmates baloney and cheese.

Pandabear’s cellmate’s head is bashed into the cell wall one morning. That afternoon, the cellmate is moved to another pod. Pandabear plays chess with the assailant. He mostly loses. He reads crime novels, how-to-garden books, and a biography of Fryderyk Chopin. His eczema flares up. He submits a medical form. The nurse gives him a vision test and suggests he submit a dietary form. The lawyer from the Atlanta Solidarity Fund appeals the charges three times, and eventually Pandabear is granted bond. After thirty-seven days in DeKalb County jail, he is released into a crowd of forest defenders waiting in the parking lot with fruit and vegan snacks and water and Gatorade and sweaters and a ride to wherever he wants, and music or silence as Pandabear prefers.

We’re not there. We needed to get out. Impulsively we bought a ticket to Vermont, to move in with a friend we hadn’t seen in years. For a month, Signal vibrates in the background: vandalism, arrests, domestic terrorism charges. Organizers prepone the fifth week of action to ride the momentum of the media and call in reinforcements sooner rather than later. It is hard to pay attention from Vermont. The world is blanketed in thirty inches of snow, white and almost noiseless. Different owls coo here in the long nights. Come back, Magnolia texts. We leave them on read. We are having sleeping problems, dreaming of privet grabbing at our ankles, Philadelphia in uniform, being frog-marched by giant spiders toward an acrid lake.

Reluctantly, full of dread, we buy another ticket to Atlanta.

* * *

SOMETIMES IT SEEMS like an evil gray cube has hijacked the planet and multiplied into jail cells and condos and cubicles and tofu and IKEA and shipping containers and parking lots and tombs. Like industrial civilization is a religion organized around worshiping the cube, digging ever deeper quarries, building ever drabber monuments, coordinating unfathomable oceans of more-than-human energy to produce and profuse and proliferate cubes to put the bodies in. We get it: the cube’s cool smoothness, its reassuring regularity. The jungle it steamrolled and conquered is barbarous, malarial, obstreperous, twisting in the wind.

We stay overnight in New York, which feels like Cop City already. Military men in bulletproof pants march in formation through Penn Station, intimidating weary people waiting for trains: no benches, no sitting on the floor. The TSA beeps our belongings. We shuffle along an endless line to fly from one concrete desolation to another, fart carbon into the ozone, and return to our cruel city to defend the damaged landscape we’ve been doomed to love.

We take off into the morning. Manhattan grubs greedily into the sky. Container ships queue up out into the ocean, minuscule on the roof of the gleaming deep. Babylon sprawls: Philadelphia, Baltimore, DC. The view from the air turns industry into entomology. We watch aloof, above, transfixed, as out the window something almost glorious rusts and crumbles into landfill, and colorless cube metastasizes over green world.