Neoliberalism Is the True Villain of ‘Joker’

In its depiction of an austerity-wracked Gotham, Todd Phillips has made one of the most subversive and left-leaning major films of 2019. Joaquin Phoenix stars as Arthur Fleck in "Joker." (Warner Bros. Pictures)

Joaquin Phoenix stars as Arthur Fleck in "Joker." (Warner Bros. Pictures)

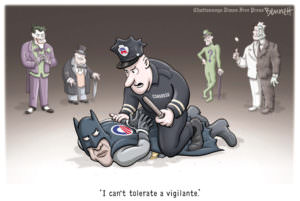

After 11 years of inundating cineplexes with status-quo defending super cops and soldiers, Hollywood has finally given us a blockbuster movie with a protagonist willing to fight for common people against the economic system oppressing them. He just happens to be a comic book villain.

“Joker” has, at best, a tenuous relationship to its DC Comics source material. In an homage to Martin Scorsese’s early work, Todd Phillips’ film serves as a dark character study of Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), a professional clown living with his ailing mother in a tumultuous early 1980s Gotham City.

The film follows Arthur as he tries and fails to smile through his fight against mental illness, poverty, loneliness and severe depression. He is utterly powerless to slow down the decay of his mental state and at one point even considers committing a crime in hopes of being recommitted to Arkham State Hospital.

Arthur’s only moments of happiness come from entertaining children and watching television with his mother—specifically a late-night show hosted by Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro), a nod to Rupert Pupkin’s idol Jerry Langford in “The King of Comedy” (1982). When the machinery of capitalism strips Arthur of even those modest pleasures (along with his access to therapy and medication), the movie reveals its true nature—not as a prestige drama but a pulpy revenge thriller.

Much has been written about the politics of “Joker,” and almost all of it wrong. It is certainly not a “toxic rallying cry for self-pitying incels,” as IndieWire’s David Ehrlich described it. Fleck’s anger is not aimed at women or people of color but specifically at those who have wronged him: the billionaire his mother used to work for, a trio of Wall Street goons on the subway and finally the celebrity who mocks his disability on national television.

The violence of “Joker” has been similarly pilloried. It is truly shocking, but that is because the film takes human life seriously. Only a handful of people are killed during the film—far less than you’d see Iron Man or Captain America kill in an opening fight scene—and each is genuinely disturbing. But Fleck does not commit murder because he’s mentally ill. Instead, his violence is a response to that which he experiences as a result of his mental illness. Beatrice Adler-Bolton of the podcast Death Panel called the film the “‘I Spit on Your Grave’ of medicalization.” It’s a revenge flick for those pulverized by a system that renders them invisible.

The true political implications of “Joker” center on Bruce Wayne’s father and the film’s antagonist, Thomas Wayne. Whereas the comic book character is a generous philanthropist, the Wayne of “Joker” is recast as a Mitt Romney-like figure who uses his immense and unearned riches to push his way into politics. His sneering disdain for those who haven’t “made something of themselves,” with its faint echoes of the then-Republican candidate for president’s 47% remarks, severs the film from the Batman lore. No longer is wealth a tool for Gotham’s benefactors to help the less fortunate but a means to a sinister, real-world end—the power to control, dominate, mock, abuse and scorn those who don’t have it.

“Joker” subverts the Batman mythos by suggesting the Waynes were not the innocent victims of a robbery gone wrong. Rather they are killed in a deliberate act to stop billionaire Thomas Wayne from becoming mayor and exerting still more power over the proletariat. The Bruce Wayne in this universe does not need to hunt criminals in hopes of finding the person responsible for his parents’ death because in “Joker” that person is his father.

For much of the film, Fleck is bemused by but disconnected from the anti-wealth demonstrations that his killing of three Wall Street brokers (and Wayne employees) inadvertently inspire. “KILL THE RICH: A New Movement?” one newspaper headline asks as masked “clowns” riot against the wealthy and hold signs demanding an end to their predations.

Fleck doesn’t quite see his part in all this, even as the funding for his treatment is cut by austerity measures and a billionaire ignores pleading from Fleck’s mother for financial assistance. But as the film reaches its climax, Arthur is literally and metaphorically embraced by this mass movement. No longer is his alienation atomized; Fleck and the audience understand that he is channeling the righteous anger of the sick, the poor and the downtrodden.

In a dream-like sequence—that may or may not be one of Arthur’s many fantasies—a crowd of clown-faced protesters wills the injured Arthur to his feet and he begins to dance, blood streaming out of the corners of his mouth as he smiles in classic Joker fashion. Arthur looks in wonder at a new world he has created in which people are no longer invisible because they’re ill, no longer crushed because they are poor, no longer forced to smile through the violence they suffer. They are no longer powerless.

Setting the film in 1981 serves the dual purpose of grounding it in the gritty New York of “Taxi Driver” and placing the film in the early days of our current global neoliberal order. Although Arthur Fleck declares he is not political, it’s impossible to view the film as anything other than a condemnation of the austerity and immiseration ushered in by corporations like Wayne Enterprises with the aid of politicians like Ronald Reagan. The film makes clear that when people are only as valued as their ability to produce profit, they will invariably fight back. “The greater danger to society may be if you DON’T go see this movie,” wrote documentarian Michael Moore in a recent Facebook post. “Because the story it tells and the issues it raises are so profound, so necessary, that if you look away from the genius of this work of art, you will miss the gift of the mirror it is offering us.”

That Todd Phillips has smuggled this deeply scornful view of the established order into a comic book movie underwritten by a major corporation is what makes “Joker” so subversive. It is increasingly uncommon for blockbuster fare to challenge audiences on a moral or political scale, but by conceiving the film as a throwback to rebellious New Hollywood cinema, Phillips has made perhaps the most left-leaning major release of 2019.

With a recession on the horizon, unchecked climate change propelling us toward global catastrophe and a political system unwilling or incapable of addressing the widening gap between the haves and the have nots, we will likely look back on the controversy surrounding “Joker” as quaint. While the film is set in the past, the class-based uprising it depicts is an optimistic glimpse into a future in which the invisible and marginalized rise up and take to the streets.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.