Murales Rebeldes

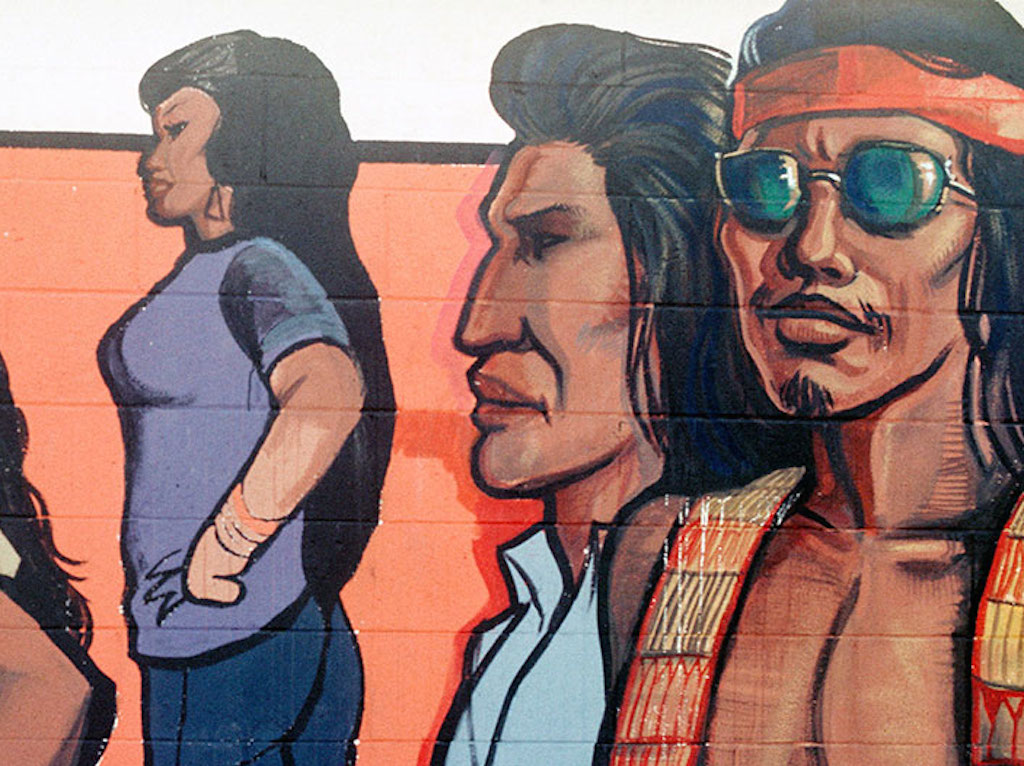

This book's histories of prominent, socially conscious Chicana/o murals in L.A. speak eloquently to the need to preserve artistic freedom. From the cover of "Murales Rebeldes!: L.A. Chicano Murals Under Siege." (Angel City Press)

From the cover of "Murales Rebeldes!: L.A. Chicano Murals Under Siege." (Angel City Press)

“Murales Rebeldes!: L.A. Chicano Murals Under Siege”

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

A book by Erin M. Curtis, Jessica Hough and Guisela Latorre

In 1932, the great Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros painted “América Tropical,” a large fresco mural, during his six-month stay in Los Angeles. The sponsors of the mural requested the artist produce a work that depicted a benign “nature” theme that would add a colorful aesthetic dimension to the Mexican-oriented marketplace of Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles. That venue recreates a romanticized vision of old Los Angeles and has been a tourist attraction for many decades with colorful vendors, restaurants, strolling musicians and other commercial enterprises.

The final artwork, however, reflected Siqueiros’ overtly communist ideology, an ideology that was presumably well known to the sponsors. The artist had no intention of creating a pleasant visual appendage to capitalism. Instead, his work was a stark critique of American imperialism and its devastating effects on indigenous populations. The centerpiece of “América Tropical” featured a Mexican-Indian on a cross, capped by an intimidating American eagle. The point was clear and dramatic: America was an oppressive society that metaphorically crucified its marginalized populations of color. Now, 86 years later, that visual message is frighteningly relevant as ICE agents round up undocumented immigrants, and Latinos are routinely subject to racist harassment and practices.

The mural had been whitewashed—censored—and quickly faded from public view until its 2012 restoration, a pale echo of its vibrant origin. The conservative interests of the era obliterated a powerful artistic expression that attacked social and economic injustice. But “América Tropical” became the model for later generations of Chicana/o political murals because of Siqueiros’ political militancy and artistic excellence; tragically, it also became a nefarious precedent for artistic censorship in Southern California.

“Murales Rebeldes!” is a compelling and sometimes depressing account of the censorship and neglect of a groundbreaking tradition of public art since the 1960s and 1970s in the United States. The authors skillfully document the disconcerting fate of several prominent Chicana/o murals in the Greater Los Angeles area in recent decades. Many of these works have made remarkable contributions to American, socially conscious art. In the region, these works played a powerful role in bringing Latina/o history and struggles to wider public audiences, most importantly to people who viewed them in the ordinary course of their daily lives. The book highlights several of the stellar artworks that were under siege, censored, destroyed, damaged, abandoned and, above all, devalued.

No longer available for audience pleasure and educational benefit, these murals nevertheless speak eloquently for the need to preserve artistic freedom. They also remind public authorities and private businesses that Los Angeles was formerly the mural capital of the world. It reflected a robust creative movement that enabled artists from neglected communities, especially Latina/os and African-Americans, to communicate provocative and often trenchant expressions rarely seen in mainstream educational, as well as media and artistic outlets and circles.

The authors have selected seven particularly significant murals that have been lost because of political or economic pressure, or sheer neglect and disrespect. Included with each work represented is substantial material about the artist’s political and aesthetic intentions. The authors include impressive photographic documentation for readers to understand (and mourn) the cultural massacre that has previously remained hidden from widespread public view.

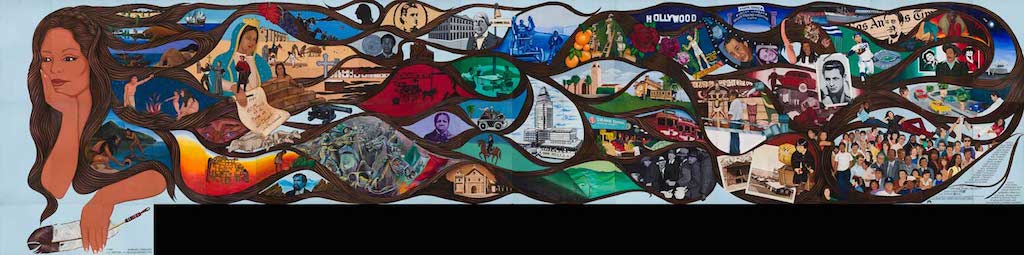

Tellingly, the first mural controversy the authors document is Barbara Carrasco’s “L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective.” Carrasco is one of the nation’s premier muralists, and she also works in several other artistic forms. Throughout her long career, she has been consummately devoted to social justice issues in her visual social commentary. Her banners and posters for the United Farm Workers, for example, have earned her national visibility. She has also created mural works in several other countries.

But her censored Chicana and feminist mural may well be her crowning artistic achievement, and it remains, although in storage, one of the most powerful and important murals of the late 20th century. In 1981, the now-defunct Los Angeles City Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) awarded Carrasco $7,000 to design, paint and mount her mural on a McDonald’s in downtown Los Angeles. Carrasco worked with many assistants, including children, and conducted extensive research into the history of Los Angeles. She paid special attention to episodes generally omitted in standard celebratory texts.

Among the events and details that she painted in her mural were an 1871 mass lynching of Chinese workers; an image of Japanese people being transported to concentration camps under the infamous Executive Order 9066; the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots; the crucified Indian from the 1932 Siqueiros mural; and many others, including some major heroic figures from many ethnic and racial communities. Linking everything together, with stunning beauty, is a striking image of a young Chicana, based on the artist’s sister, whose long hair unites the entire panorama throughout the large composition painted on 43 panels. The final product is a magnificent visual history of Los Angeles from prehistoric times to the mural’s creation in 1981.

The CRA, however, objected strongly, claiming that Carrasco “emphasized the negative.” Agency officials nevertheless argued that the dispute was over design, not content. The artist resisted, refusing to take anything out. She sought out other artists, scholars and community groups to support her.

I followed the battle closely but was no neutral observer. Carrasco telephoned me and requested my support, which I eagerly gave. I had one especially memorable experience during that battle. I had a discussion (really a debate) with a CRA official on KPFK, the Los Angeles Pacifica radio station. That representative repeated the official line. She said that there was no attempt to censor this mural. Rather, she asserted that the CRA was only making suggestions to improve its overall artistic quality. When I pressed her about some of the controversial details, she replied that these made the mural seem “too busy.”

I have told my UCLA students for decades about my impulse and my actual response to that ludicrous comment. I wanted to reply with a quick and effective answer: Bullshit! But I was painfully aware that the Pacifica station had lost only a few years earlier in the U.S. Supreme Court in the George Carlin seven “filthy words” controversy. I had no desire to put KPFK in any legal jeopardy. So instead, I replied that the representative’s comment was a transparent cover for the CRA’s political censorship of a socially conscious Chicana mural, and that she was using the language of artistic criticism to conceal the agency’s real political objective. My reply was on point, but the word “bullshit,” in this instance, would have been an appropriate preface to my retort.

Except for two brief appearances in Los Angeles Union Station, most recently in late 2017, Carrasco’s panels have remained in storage, unseen by people who could gain profoundly from its historical perspective and artistic grandeur. But at least it lives on through this book and through the efforts of scholars and teachers who present it in reproduced form.

“Murales Rebeldes!” also effectively documents the destruction of a major mural by two of Carrasco’s fellow Chicana muralists. In 1995, Yreina Cervantez and Alma Lopez painted “La Historia de Adentro/La Historia de Afuera” (The History From Within/The History From Without) on a wall of the Huntington Beach Art Center’s parking lot. This visually dynamic, 105-foot-long mural was extremely well researched, containing “controversial” imagery that reminded conservative viewers about historical events that uncomfortably contradicted conventional and romanticized visions of the local past.

Japanese immigrants Martha and Raymond Furuta, for example, were prominently displayed, dancing tenderly in their senior years. They arrived in California from Japan in 1912, but suffered the severe racism and hostility against Japanese-Americans after the outbreak of World War II, leading to their internment in concentration camps. Cervantez and Lopez used public art here to remind viewers of an unsavory chapter in Orange County, Calif., history.

Another Orange County family, the Mendezes, was also prominently featured in the artists’ mural. That courageous family was at the center of the landmark desegregation case in 1947 that held that officially sanctioned school segregation against Mexican-American children in Orange County was unconstitutional. This case was a major building block toward the historic Brown v. Board of Education decision seven years later that ended all racial segregation against minority students. The Mendezes were legal and political pioneers, justly deserving their forceful portrayal in this mural.

Once again, a powerful mural served as a major historical corrective even as it added visual eloquence to a local community. But after several significant incidents of graffiti tagging, the new leadership of the Huntington Beach Art Center informed the artists that the mural could not be saved. Although Cervantez and Lopez mounted a campaign to rescue the work, it was eventually painted over. Once again, a venerable artistic treasure was lost.

However disfiguring graffiti can be to public art, its damage is entirely reparable. The reality is that too many people were uncomfortable with a large mural about the history of people of color in a predominantly white, Orange County community. Images of Asians and Latinos disrupt the consciousness of much of the white populace, even when such bias is implicit and more difficult to address. “La Historia De Adentro/La Historia De Afuera” is as much a victim of the real political correctness of recent times as was “América Tropical” in the 1930s.

This extraordinarily informative book also narrates the story of one of the most unusual and engaging murals since the start of the modern mural movement in the late 1960s. In 1972, artist Willie Herrón painted “The Wall That Cracked Open” in one night on an alley wall in Los Angeles. The anguished faces in the mural were Herrón’s emotional response to his brother’s stabbing in a gang incident—an all-too-common feature of life in impoverished communities of color. The mural features two Latino brothers facing each other and the artist’s grief-stricken grandmother holding a crucifix. The top of the mural depicts Herrón’s wounded and bleeding brother.

But the most striking element is how he incorporated existing gang graffiti into the mural itself and left room for even more—a constantly evolving work of public art. This dramatically countered the prevailing anti-graffiti efforts of city officials. He repudiated the vision that murals should be an antidote to graffiti and instead included the tagging as part of his desperate plea to end the violence in this and other Latino neighborhoods. The result was an unusually powerful social and aesthetic public artwork. It fundamentally challenged the definitions of both art and graffiti. The text in “Murales Rebeldes!” provides a perceptive analysis of these continuing cultural and artistic controversies.

In 1998, however, Herrón discovered that Los Angeles County workers had buffed out the graffiti section of this mural in its graffiti abatement program. The loss of the graffiti essentially destroyed the mural’s underlying vision. Although the artist is an expert restorer, “The Wall That Cracked Open” could not be returned to its original state even with his restoration. With new graffiti and tagging (some of which Herrón describes as simple vandalism), the result is a fundamental loss of a particular historical moment. In 2017, the building on which the mural is painted was sold to a private investment company. Its future is therefore problematic, perhaps further eroding the proud legacy of Chicana/o murals in Southern California.

“Murales Rebeles!” effectively addresses the loss of several other iconic murals throughout the region. In his perceptive afterword to the book, journalist Gustavo Arellano decries the sad state of Chicana/o murals throughout Southern California. He understands that censorship and political interference with socially conscious public art have been major factors in the suppression of Latina/o history. But he identifies an even more pernicious factor: public indifference.

As he indicates, few people care enough about these remarkable public artworks to ensure their continued vibrant presence as crucial reminders of history and political struggle. This is especially dangerous at a time when a reactionary U.S. president has regularly aimed racist insults at Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. Donald Trump’s hateful words have empowered others to put people of color under siege. The suppression of Chicana/o murals is merely one aspect of the suppression of Chicana/o people generally.

Fortunately, signs of resistance have emerged. This book itself and its associated exhibition presented by the California Historical Society in downtown Los Angeles, from September 2017 to February 2018, and then in San Francisco from April 2018 to August 2018, represent a major public response to the loss of these vital public artworks. Organizations like the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) and the Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles work vigorously to conserve, restore and protect existing murals and encourage and support new public artworks, especially those with compelling historical and political content.

Above all, broader political resistance is required, not only to save the murals, but also to fight against the burgeoning racism and xenophobia currently ravishing the national landscape. The deepest objective of all the murals under siege is for viewers to discover the power of historical memory. That power, in turn, can inspire people to take control of their own lives. It can encourage them to organize against those forces that would deny them their histories, as well as their very dignity, as human beings.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.