Movies About the Movies: ‘Marilyn’ Charms, ‘The Artist’ Bombs

Basically, I love movies about moviemaking And basically, Hollywood loves making these movies They have been a well-established genre since Chaplin was a pup And a pretty good genre it is—there’s nothing like self-regard to bring out the feverish in people Basically, I love movies about moviemaking .

Basically, I love movies about moviemaking. And basically, Hollywood loves making these movies. They have been a well-established genre since Chaplin was a pup. And a pretty good genre it is—there’s nothing like self-regard to bring out the feverish in people. The trouble is, audiences are not always as interested in show business sagas as you think they might be. Movies we have eventually come to love for their giddy melodrama (“Sunset Boulevard”) or their high-stepping high spirits (“Singin’ in the Rain”) were, relatively speaking, flops on their original release—possibly because their makers seemed to be having too much fun with their subjects. We take movies seriously, I think, and if the drama of their making doesn’t match up to our tragic expectations (or our carefree hopes), we tend to withdraw into grumpiness for a while.

There are a few exceptions, of course. You can’t beat “I’m Mrs. Norman Maine” for a kicker to the lugubrious “A Star Is Born,” version No. 4 of which goes into production next summer. And, bless its heart, Hollywood, after something of a gap, is back at it again this season, though with decidedly mixed results.

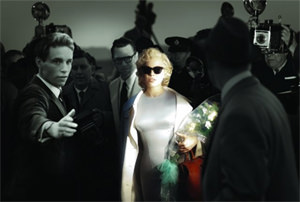

The good news is “My Week With Marilyn,” which is about a naif named Colin Clark (Eddie Redmayne) who’s eager to shed his incipient stuffiness and have a showbiz fling. Clark, third son of the renowned art critic Kenneth Clark, signs on as third assistant director (read gofer) on Laurence Olivier’s 1956 production of “The Prince and the Showgirl.” Soon enough, he is executive in charge of Marilyn Monroe—mostly because he has no ax to grind. He’s just a nice kid with good manners and a helpful way about him—too innocent, really, to be anything else.

Marilyn, wonderfully portrayed by Michelle Williams, is, of course, Marilyn as legend has come to portray her: late to the set, unable, at times, to speak her lines, drugged with sleeping potions and dragging behind her both a grudging new husband, Arthur Miller, and her god-awful acting coach, Paula Strasberg (Zoë Wanamaker). What makes her bearable is that she is, betimes, charming and playful and, occasionally, more than up for her job.

This does not entirely impress Olivier, who is played, brilliantly I think, by Kenneth Branagh, who doesn’t look at all like the lordly actor but, in flashes, channels him uncannily. Olivier was, among other things, a consummate professional, and he couldn’t abide Marilyn’s ways, yet he was sometimes seduced by her despite himself.

All of this is a true (all right, truish) story, based on diaries and a book Clark wrote, and the direction by Simon Curtis and the script by Adrian Hodges are feather-light. We don’t learn anything about Marilyn that we did not know after a half-century of “legendary” twaddle. She was totally impossible, just as everyone who ever worked with her said she was. Yet at this point she was, I think, possibly salvageable. At least this movie makes it seem so. It does not deal in portent—the tragedies to come are not particularly hinted at. Williams makes her a kind of playful child—gifted, whimsical, perhaps more knowing than she seems, and sometimes a lot of fun to be with.

There is no consummated sex between Clark and Monroe, but that does not mean the thought does not cross their minds. Which seems to me just right. Essentially they just have what the title implies—a frivolous, playful week. It would be easy to overpraise this very slight little picture. But its heart is in the right place. Marilyn was now and then, here and there, kind of fun to be with. Who knew?

Writer-director Michel Hazanavicius’ “The Artist” is not for a nanosecond fun—though it works hard to be so. Basically, it is “A Star Is Born” knockoff. George Valentin (Jean Dujardin) is a silent picture superstar. Then sound comes in and career dwindles to drink and poverty until Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo), a rising star who for inexplicable reasons loves him, rescues him. You couldn’t hope to put this tired story over on anyone without some kind of a gimmick. And “The Artist” has one. It is a silent picture.

You heard that right—essentially no talk. Just lots of big takes and broad pantomime. After 15 minutes my teeth were aching from the sheer stupidity of this effort. To begin with, the overall look of the film is nothing like as elegant as that of high-silent-era movies. It looked more like a ’40s picture. Worse, the clichés of plot and characterization (I’ll exempt Valentin’s really cute dog from this criticism) rob the picture of any surprise or wonder. You are left merely with silence and high spirits. And, frankly, actors who—no surprise here—haven’t a clue about the subtleties of silent screen acting.

Let my contempt for this exercise be interrupted by a serious thought. Silent movies were not simply movies that didn’t talk. They are at many levels a lost art—a subject, now, for a shrinking band of cultists. Personally, I don’t particularly mourn them, and sometimes I am still strangely moved by the elegance of the mighty effort that went into their tongueless attempt to communicate with us. If the movies had not learned to speak, there is just the slightest chance that silent film might have developed into a unique form of symbolic and poetic expression. Be that as it may, this strange and lovely form does not deserve that vulgar and witless travesty that has so often been its fate, and which reaches a peak in this truly worthless film.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.