The Miseducation of Native America

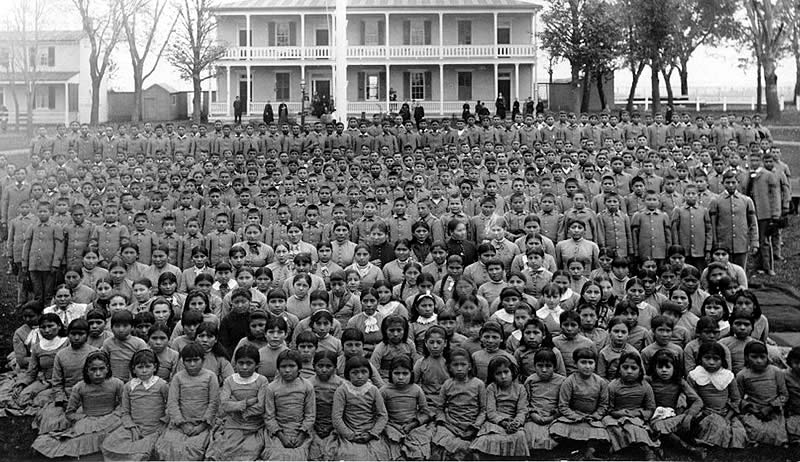

Western, white schools still serve as punitive places that destroy the spirit and morale of native students. Students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania circa 1900. Carlisle was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. All of the school property is now a part of the U.S. Army War College. (Frontier Forts / Wikimedia)

Students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania circa 1900. Carlisle was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. All of the school property is now a part of the U.S. Army War College. (Frontier Forts / Wikimedia)

White school systems will always fail Native American students unless or until there is a fundamental shift—a transformation—in the way that white schools approach native students.

Western, white schools historically were designed as punitive places intended to destroy the spirit and morale of native students. The United States government referred to this process as killing the Indian “and saving the man.” Everyone knows that. But not everyone knows that in 2017, statistically, Western, white schools are still serving as punitive places that destroy the spirit and morale of native students.

It is a well-chronicled tale: During much of the 1800s and 1900s, Western, white schools stole native children and cut off native students’ hair to demand absolute obedience and conformity. That is historical record. Problem is that today, those schools’ neoliberal descendants continue to disproportionately expel, suspend and push native students into the school-to-prison pipeline and place native children in special education to demand that same absolute obedience.

For native students, cultural difference is seen as problematic, and for those behaviors, statistically, students will find themselves forced outside the educational system. Native educators and parents have made many efforts to redefine the way native students are educated within Western, white educational systems. But they are whitesplained, rebuffed and rejected as evidenced by modern examples of many schools disallowing natives students from wearing eagle feathers on their graduation caps, requiring native students to cut long hair and, of course, criminal underfunding of native education.

Native educators have worked hard to rewrite the vicious historical narrative and recreate Western, white education’s relationship to native students. But resistance to those efforts has been powerful. Because of that resistance, unless there is a fundamental transformation of that system, those schools will continue to do damage to the bulk of native students.

As they have always done. It’s not an accident.

Recently, Rebecca Clarren wrote a very informative and powerful piece for The Nation titled “How America Is Failing Native American Students.” It was a well-researched and well-thought-out piece that shared a lot of data and showed some of the reasons why native students in general struggle within Western, white educational structures. Clarren even did some digging into the genesis of white people educating native people in American schools. It was a solid article, and I recommend that any educators who work with native communities read that important piece.

It was necessary. She’s an amazing journalist. I’m thankful that she brought the horrors facing native students in white education into a mainstream light.

But as necessary and powerful as her piece is, we must go even further to understand how profoundly history still informs native students’ educational outcomes. This ugly history infects the connective tissue between native students/families and white education on such a molecular level that simple adjustments and tweaks will not be enough ever to make native kids feel wanted in white schools or make their families feel that their children are safe.

As amazing as Clarren’s piece is, it was written from a frame that did not acknowledge the depth of the violence that white education did to native children and families. That lack of acknowledgement allowed her to remain hopeful that white schools could rehabilitate the relationship with native students and families if schools, teachers and administrators were willing to take certain steps. Her piece did not suggest that there had to be a transformation to white educational systems—instead, it hinted that mere modifications would be sufficient. Those modifications made complete sense—for example, more native teachers, native language and history, the hiring of native champions and advocates within school districts. Those are absolutely necessary for a student of any color to simply be functional within educational systems. We’re talking about kids—of course they want to see more of themselves in those systems.

But none of those modifications—by themselves or in the aggregate—are enough to make native students feel wanted or safe. The fact is that white schools never stopped being places of punishment of native students—so we cannot in good conscience say, “That is a thing of the past.” That consistency in the maltreatment of native students therefore requires a fundamental transformation of the relationship between student and institution in order to see a shift in those outcomes for native students.

What does transformation look like?

Transformation requires discomfort and cost, whether one is talking about transforming a house, their body or a relationship. Something has to change. There are three basic steps to making this change; easy in theory, but difficult in practice.

The first uncomfortable step is publicly acknowledging that there is a problem. White educational systems in the U.S. have not acknowledged, publicly or otherwise, that there is any reason other than merit and bad home situations why native students are not performing well in their classrooms. In other words, white institutions shift the burden from explaining why the system fails native students to putting the impetus on natives to show why the individual is falling short. White educational systems do not routinely acknowledge the brutal history of similar educational systems vis-a-vis native students nor do they acknowledge that the numbers show that they still routinely do similar violence today. This step is almost entirely missing in conversations about the education of native students. Instead, the conversations usually devolve into “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” meritocracy drivel.

The second uncomfortable step is asking the aggrieved party for their acknowledgement of issues. Many times in “reconciliation” conversations, if the perpetrator of a problem acknowledges a problem, that party also begins to etch out the process that they will follow in order to rectify the situation. That party is, oftentimes, ready to do certain things in order to make the situation better—and they believe that they know how. The truth is that forgiveness belongs to the forgiver. The truth is also that only the forgiver—if they choose to forgive—knows what will make it right. When I see schools throwing money at native people for this program and that program to make up for historical, institutional harms—hey, maybe that might be right. But many times it is just throwing money at a problem; why not ask the aggrieved party themselves? If we seek transformation, we must be willing to listen to and defer to the brilliance of the community that we’re serving.

Finally, the third uncomfortable step in seeking transformation of Western, white educational systems in their relationships with native students is different behavior. It seems obvious, but if suspending native students for the same behavior for which white students get detention (or a verbal warning) and your school wants to transform the relationship with native students, stop doing that behavior. If your textbook spends 2,000 words teaching about Christopher Columbus but no words teaching about the tens of thousands of years that natives lived on these lands before Columbus, stop teaching out of that damn book!

As you can see, we’re eons away from transformation of these systems. There has been very little conversation about, or acknowledgement of, the harms that white educational systems commit(ted) on native students. There have been no questions asked from our communities regarding how we see the system transforming and becoming better. Finally, white schools largely have not changed the behaviors that resulted in so much destruction of native communities. As a result and until this happens, native students will largely have the same outcomes that we have always had in Western, white educational systems.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.