Merv Griffin’s Bodyguard of Lies

The not-so-secret gay sex life of Merv Griffin has once again raised the specter of the obituary outing, not to mention the power of prejudice to intimidate even the rich and famous.

When Hollywood mogul Merv Griffin died on Aug. 12, queer-savvy media watchers wondered whether notices of his passing would maintain his preference for passing as straight. In recent years, celebrity obituaries have continued the long tradition of burying the departed closet cases in journalistically closed coffins, taking the not-so-secret truth with them to the grave. Singer Luther Vandross, writer Susan Sontag and film director Ismail Merchant had all been accorded the privilege of “inning” by the press, however open a secret their homosexuality had been while they were alive. Nil nisi bonum appears to be the rule for editors, and noting that a deceased famous person was gay certainly seems to count as speaking evil.

In Griffin’s case, though, I was somewhat pleasantly surprised, as The New York Times, ” the los angeles times> the Los Angeles Times and The Washington Post all noted in their obituaries that Griffin had been the target in the early 1990s of unsuccessful palimony and sexual harassment suits, both brought by men who claimed that he had done them wrong, though in different ways, and both dismissed in court. Still, these lawsuits brought out into the open, if briefly, what had long been known in Hollywood: namely, that the divorced father of one, and highly visible public escort of Eva Gabor, was also gay. In the years since his legal outing, Griffin was sometimes questioned about his sexuality and always deflected the question with a joke: “You’re asking an 80-year-old man about his sexuality right now! Get a life!” In 2005 he told The New York Times with a sly grin: “I tell everybody that I’m a quatre-sexual: I will do anything with anybody for a quarter.”

The Associated Press, however, played the game the old way, limiting its obituary to Griffin’s early marriage:

Griffin and Julann Elizabeth Wright were married in 1958, and their son, Anthony, was born the following year. They divorced in 1973 because of “irreconcilable differences.”

“It was a pivotal time in my career, one of uncertainty and constant doubt,” he wrote in [his] autobiography. “So much attention was being focused on me that my marriage felt the strain.” He never remarried.

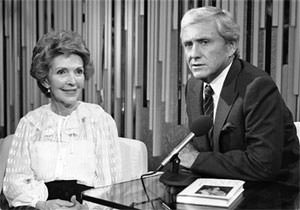

Merv Griffin’s Beverly Hills funeral was a major Hollywood event, headlined by Nancy Reagan and Arnold Schwarzenegger and co-starring Larry King, Ellen Degeneres and a host of TV old-timers such as Dick Van Dyke, Jack Klugman and Steve Lawrence. For some, the event was reminiscent of the funeral of another famous tycoon, an occasion that played a key role in launching the controversial journalistic-political tactic that came to be known as outing.

The New York gay magazine Outweek introduced the practice of outing closeted public figures, mostly politicians and show business celebrities who were unwilling to enlist in the cause of fighting AIDS. When prominent publisher Malcolm Forbes died in February 1990, the exposure of his homosexual side was not long in coming. The March 18, 1990, cover of OutWeek showed a photo of Malcolm Forbes on his motorcycle, with the bold headline: “The Secret Gay Life of Malcolm Forbes.” The article, by Michelangelo Signorile, begins with Forbes’ funeral, noting the presence among the mourners of many prominent homophobes — Richard Nixon, William F. Buckley, Al Neuharth — and asks whether they knew “that they were coming to pay homage to someone who embodied what they ultimately detested?”

Signorile concluded his article with a defense of outing Forbes. First, he noted that, “All too often history is distorted,” and the fact that one of the most influential men in America was gay should be recorded. Second, “it sends a clear message to the public at large that we are everywhere.” The third reason Signorile gave was that this story illuminated a choice made by many gay people. In researching the story Signorile tried to interview a gay man who had been close to Forbes and his family, someone who could have shed light on “the real inner workings of Forbes’ mind.”

But, after considerable thought, he decided not to speak to me. Currently living a closeted existence with regard to his own family and business, he said, “My choice in speaking to you is between myself and the greater gay community. And — at this moment — I have to go with myself.”

The Outweek story set off a firestorm of controversy about outing, with most condemning the tactic. The L.A. Times, which also editorialized against outing, named only dead people: Forbes, Rock Hudson, Liberace, Roy Cohn, Terry Dolan, Perry Ellis and Oliver Sipple; Newsweek limited itself to Forbes (reproducing the OutWeek cover photo and headline) and Liz Smith, a “favorite target” of the outers who is quoted as saying, “I may be a gossip columnist, but I do respect the right of people not to tell me ‘everything,’ and I reserve the same right for myself.” The New York Times would refer only to “a famous businessman who had recently died.” Times spokesman William Adler took a hard line, saying that the paper would not print “hearsay” even if the subject is no longer living: “The thinking at the Times is that in most cases an individual’s private sex life should not be the subject of coverage by the newspaper unless the person wishes it to be so,” Adler said. “That perspective extends through their lifetime and even after their death.”Seventeen years later, the situation is vastly different, but celebrity closets remain dangerous journalistic territory, even when their inhabitants are deceased and therefore immune from being libeled. The day before Merv Griffin’s funeral, the Hollywood Reporter, one of the industry “bibles” read by everyone in showbiz, ran a front-page story by regular writer Ray Richmond that began, “Merv Griffin was gay.” Richmond, who had worked for Griffin in the 1980s, went on to note that “Merv’s secret gay life was widely known throughout showbiz culture, if not the wider America.” Richmond made clear why he thought it important to set the record, um, straight about Griffin’s sexuality:

He certainly didn’t owe us an explanation, but maybe he owed it to himself to remove the suffocating veil he’d been forced to hide behind throughout his adult life. Then again, Merv carved his niche in the entertainment world at a time when being gay wasn’t OK, when disclosure was unthinkable and the allegation alone could deep-six one’s career.

If you’re Griffin, why would you think a judgmental culture would be any more tolerant as you grew into middle and old age? Even in the capital of entertainment — in a business where homosexuality isn’t exactly a rare phenomenon — it’s still spoken of in hushed tones or, more often, not at all. And Merv’s brush with tabloid scandal no doubt only drove him further into the closet.

While it would seem everything has changed today, little actually has. You can count on the fingers of one hand, or at most two, the number of high-powered stars, executives and public figures who have come out. Those who don’t can’t really be faulted, as rarely do honesty and full disclosure prove a boon to one’s showbiz livelihood.

Nonetheless, the elephant that was his sexual orientation never really stopped following Griffin from room to room. He could duck it for a while, but it would always find him. It’s disheartening that Merv had to die to shake it for good.

The reaction to Richmond’s article was swift and effective. Recently appointed editor Elizabeth Guider, a Variety veteran who had taken over The Hollywood Reporter less than a month before, seemingly caved in under pressure from her corporate bosses at Nielsen Business Media or from one of Griffin’s companies, which threatened legal action (although, of course, there was no legal basis for such a threat). In any event, the article was pulled from the website, but in the age of the Internet, of course, the cat was long out of the bag. As the story bounced around the blogosphere, it clearly was beyond containment, and THR restored the story, although in a less prominent spot. As Raymond later wrote on his blog:

Incoming editor Elizabeth Guider opined upon reflection that the column was not “malicious, mendacious or unfair-minded” and therefore [she] was comfortable not merely with its legality but its message as well. She understood that it’s sometimes the job of columnists to shake up the status quo as well as to “spark more discussion and deal with different viewpoints. That’s what free speech is about.”

Reuters, however, which had run the story when THR first posted it, took it down and did not put it back. Reuters explained: “This was a story from The Hollywood Reporter that ran as part of a Reuters news feed. We have dropped the story from our entertainment news feed, as it did not meet our standards for news.” Officials of the news service did not explain, however, why the article seemed to meet their standards when they originally ran it (Yahoo News, which picked up the Reuters story, kept it up even after Reuters took it down).

So, how far have we come in the years between Malcolm Forbes’ and Merv Griffin’s funerals? Quite a way, to be sure, but at least for many power-wielders, things are much the same. Hollywood, like its East Coast counterpart in image manipulation, Washington, D.C., is endlessly engaged in the selling of constructed personae on the mainstream media’s pages and screens. If, as Churchill said, in wartime truth has a bodyguard of lies, then Hollywood’s image factory is always at war. Its defensive strategy relies heavily on a fifth column within the ranks of the press: gossip writers. The progeny of Louella Parsons and heirs of Hedda Hopper follow in the footsteps of their infamous ancestors, “two vain and ignorant [columnists who] tyrannized Hollywood” in the 1940s, as they were characterized by historian Otto Freidrich. Early in the 20th century the component parts of the image-manufacturing complex were firmly in place: On the one side studio publicists, publicity agents and public relations flacks, and on the other side an array of media writers ranging from freelance stringers to writers working for supermarket tabloids and magazines, whose contemporary counterparts work for mainstream personality gossip magazines like People and US, television programs like Entertainment Tonight, syndicated gossip columnists that reach millions of readers through their local newspapers, and the latest venue, commercial and amateur websites. But despite the occasional adversarial pretense, these groups really collude in providing the sort of gossip they believe the public wants to know. Gossip may not have the journalistic respectability of “hard” news, but it is an increasingly visible feature of the media landscape.

It may be a commonplace of journalism courses that the ultimate standard for news media is honesty — never knowingly to report something that is untrue, even if the “whole” truth may not be reportable for a variety of reasons (such as protecting one’s sources). But when it comes to celebrity gossip, “The standards are different,” said Jerry Nachman, then editor of the New York Post. “That’s why I always say gossip pages should come with little warning labels: The rules of regular journalism were not followed in reporting these stories.”In the case of homosexuality, we begin with a topic that already puts a strain on the rules of journalism. Former New York Times columnist Roger Wilkins, the first black writer appointed to the paper’s editorial board, said that during his two years as the urban affairs columnist in the late 1970s, only three of his columns were killed — and two of them were on gay topics. So, it should surprise no one that one of the most common departures from the rules of regular journalism is the collusion of gossip writers, and other, more “respectable” journalists, in maintaining the security of celebrity closets.

During the outing furor of the early 1990s, gay journalist Randy Shilts, while not supporting outing, did describe the system clearly:

Hundreds of publicity agents in Hollywood and New York make their living by planting items in entertainment columns about whom celebrities are dating. Many of these items are patently false and intended only to cover up the celebrity’s homosexuality. Many newspaper writers and editors know this and cheerfully participate in the deception because the bits help fill their columns. Editors who would never reveal that a public figure was gay have no problem with routinely saying that same person is straight.

“Celebrity publications are lied to up, down and sideways,” said a longtime editor at Ladies Home Journal and US, but this is highly disingenuous and ignores the fact that celebrity writers and publications are willing participants in a process that might be called inning. The gossip writers, many of them lesbian or gay, who speculated about when Malcolm Forbes would marry Elizabeth Taylor, or when Merv Griffin would marry Eva Gabor, knew what they were doing.

When singer Luther Vandross died in 2005, the media obituaries politely ignored the widespread speculation that he was gay. Using familiar inning code in their Vandross obit, the AP reported that, “the lifelong bachelor never had any children, but doted on his nieces and nephews. The entertainer said his busy lifestyle made marriage difficult; besides, it wasn’t what he wanted.” As blogger Pam Spaulding put it:

The real problem is that the news media, which has no problem recounting the endless het romances of stars (real or alleged), is squeamish about even asking a star whether or not they are gay — how is this journalism? In Vandross’s situation (as well as in the posthumous media de-gaying cases of Susan Sontag and Ismail Merchant), the coverage bends over backwards, straining any sense of credibility, to avoid any fact-finding about the subject in question that might reveal they were gay, even if the person was openly gay in their social circles, but not to their fan base. Why is there a need to preserve a straight fantasy in death?

In the end, of course, the issue is not whether Merv Griffin’s secret would be buried with him. In the age of Wikipedia, it’s a given that anyone interested enough to Google Merv would quickly get the gist of the story, if not the gory details, or even the less savory details, such as those recounted by Michelangelo Signorile in his 1993 book, “Queer in America,” in which an unnamed Hollywood “Mogul” is described as firing men from his company for being openly gay. The real point of the episode is the enduring power of the Hollywood closet that held even a billionaire locked in its embrace, paying homage to the presumed prejudices of the public.

Dig, Root, GrowThis year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

This spring, stand with our journalists.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.