Man-Made Climate Change Increases Risk of Extinctions

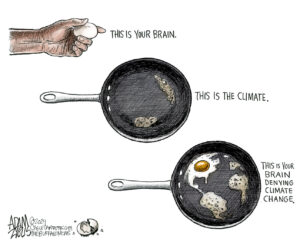

New research warns that the survival of a sizeable proportion of life on Earth is in doubt as fossil fuel emissions push up global temperatures.

By Tim Radford, Climate News Network

The marbled salamander is increasing its distribution and range in the eastern U.S. in response to warming winters. (Mark Urban)

This Creative Commons-licensed piece first appeared at Climate News Network.

LONDON — Climate change threatens one in six of the world’s species with extinction, according to new research.

The higher the average rise in planetary temperatures because of man-made global warming, the faster the rate of biodiversity loss — and the greater the survival dangers for a significant proportion of life on Earth.

Two studies published on the same day in the same journal reach the same conclusion: that climate change from any cause is bad for an ecosystem’s health and presents dangers of species extinction.

That the natural world is responding uneasily to man-made, or anthropogenic, climate change is not in doubt. In the last two years, scientists have shown that it can be the last straw for a population already under pressure, or so vulnerable it can no longer survive without human help.

Change habitat

It can change the habitat and climate in which plants and animals have evolved, but offer no safe place to which to migrate, and it can provide the conditions for new threats to flourish.

Genomic evidence shows that, in the recent past, it can constrict the numbers available for breeding, and ancient palaeontological evidence has linked greenhouse gas concentrations to catastrophic mass extinction.

Mark Urban, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut, US, now reports in the journal Science that a comprehensive look at the whole picture tells the same story.

His warning is that if fossil fuel emissions continue on the business-as-usual scenario, and temperatures on average reach the predicted 4.3°C increase, then one in six of the world’s species could face extinction.

“We believe the past

can inform the way we plan our conservation efforts”

There are problems with this kind of research: more than a million species have been described and named, but nobody knows, to an order of magnitude, how many species there might actually be on the planet. The living world is still largely unknown.

So Dr Urban surveyed 131 published predictions of extinction, and then subjected them to a mathematical technique called meta-analysis.

Extinction risks were higher in South America, Australia and New Zealand — all places that harboured diverse assemblies of endemic species with small ranges and, in the case of the large islands, not a lot of choice about places to which to migrate.

“Extinction risks from climate change are expected not only to increase but to accelerate for every degree rise in global temperatures,” he concludes. “The signal of climate change-induced extinctions will become increasingly apparent if we do not act now to limit future climate change.”

Seth Finnegan, a biologist at the University of California Berkeley, and colleagues report in Science that they looked at the marine fossil record during the climate ups and downs of the last 23 million years.

They identified 2,897 different fossil genera from six major groups — marine mammals such as seals and whales, sharks, bivalves, gastropods or snails, echinoids and corals – and used the evidence to arrive at a baseline for a “natural” extinction risk that could not be blamed on humans.

Vulnerable species

“Our goal was to diagnose which species are vulnerable in the modern world, using the past as a guide,” Dr Finnegan says.

“We believe the past can inform the way we plan our conservation efforts. However, there is a lot more work that needs to be done to understand the causes underlying these patterns and their policy implications.”

Not surprisingly, those vertebrates with small geographic ranges were at the highest risk — with whales, dolphins and seals more likely to face extinction than invertebrates such as sharks and corals.

The tropical waters of the west Atlantic and the west Pacific provided the most vulnerable ecosystems in the last 23 million years, and these regions today are predicted to experience the fastest rates of climate change and the greatest human impact in the shape of habitat destruction, overfishing and pollution.

The researchers also established another measure of extinction risk: in terms of species survival, it is 10 times more perilous to be a mammal than a clam.

Dig, Root, GrowThis year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

This spring, stand with our journalists.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.