Letter from Nuevo León: ‘As If the Earth Swallowed Them’

For residents of Northern Mexico, what is an economic boom worth when it brings violence and disappearances? An embroidered heart with a message that reads in Spanish: "Your daughters are looking for you" hangs from a tent on International Day of the Disappeared, in Mexico City, Wednesday, Aug. 30, 2023. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

An embroidered heart with a message that reads in Spanish: "Your daughters are looking for you" hangs from a tent on International Day of the Disappeared, in Mexico City, Wednesday, Aug. 30, 2023. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

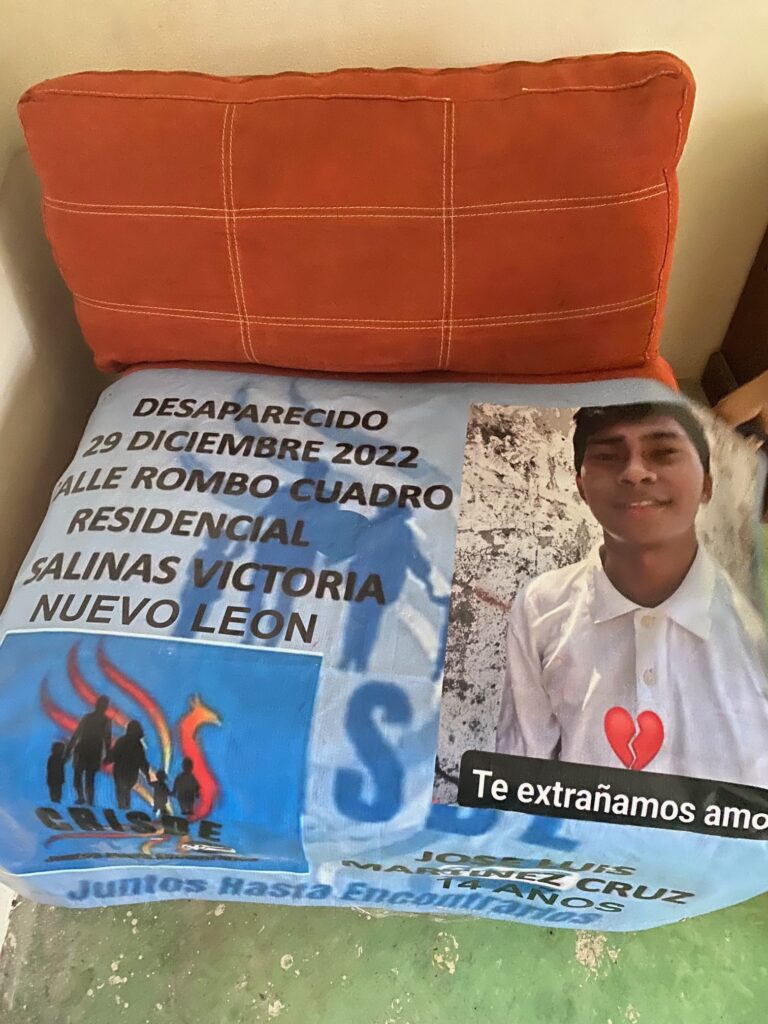

A shiny purple Ford Mustang, still in its Hot Wheels packaging, hangs on the wall in José Luis Martínez Cruz’s room in the northern Mexican state of Nuevo León. The abandoned Minecraft world the 14-year-old built with Lego bricks sits in his closet. On the armchair where Martínez Cruz used to toss his clothes, a banner with his photo and the word “DESAPARECIDO” hangs above the date he was last seen: Dec. 29, 2022. The other side of the banner reads “Te extrañamos amor.”

It was a sweltering Saturday in July when I met Martínez Cruz’s mother, Sonia Cruz Varela, in the kitchen of her home in Salinas Victoria, 25 miles north of Monterrey, the capital of Nuevo León. At the time, her third son had been missing for seven months. The 49-year-old mother spent much of our interview distracted by her cell phone, awaiting any clue that would lead to her son’s whereabouts.

Cruz lives in a working-class neighborhood on the outskirts of Salinas, surrounded by bare cement block houses that look unfinished and vacant lots filled with trash and tall weeds. The room where we sat, built from concrete blocks, had a rough cement floor. The place was brutally hot. Cruz shared with me one of the last photos she took of her son, in which he’s hugging his dog and smiling.

For 19 years, Cruz has been a cog in the celebrated machine of globalization. She assembles auto parts in one of the many factories in Salinas Victoria. Every week, between Monday and Thursday, Cruz stands for roughly 12 hours on a production line for the manufacture of car door handles. The finished products are shipped to Laredo, the busiest trade hub on the U.S.-Mexico border. At the end of her shift, she gets in the company van for the hour commute home. On Friday, Saturday and Sunday, Cruz searches for her son.

In Salinas Victoria, population 86,000, at least 31 people have been declared missing this year. Local residents say the real number is larger. These are young people who left their homes to visit friends in the evening and have not been heard from since. In some cases, witnesses saw people following them in black trucks. The same trucks have been seen arriving at houses in the middle of the night with armed men who forcibly remove residents.

As these human beings are disappearing, the city is experiencing rapid growth due to a new wave of foreign investment. Salinas Victoria sits less than three hours from the Colombia Solidarity International Bridge, the only border crossing between Nuevo León and Texas, making it ideal for the “near-shoring” of production to supply the world’s largest consumer market, the United States. Salinas Victoria is now home to industrial parks such as the Hofusan, a 2,100-acre manufacturing site built by Chinese investors, and global automotive suppliers such as Japan’s Tokai Rika and South Korea’s Hyundai Mobis. The Nuevo León government boasts that the state is primed to become a major hub for electric vehicle manufacturing, and not without reason. Tesla plans to build a new Gigafactory on the outskirts of Santa Catarina, about 35 miles southwest of Salinas Victoria.Chinese company Noah Itech is investing $100 million in the construction of its first plant in Mexico; South Korean automotive manufacturer Kia pledged $408 million. The flood of foreign investment in Nuevo León has fueled the steady expansion of the Monterrey metropolitan region toward the state’s northern border with the U.S.

This is all good news for business, but not necessarily for the residents of Salinas Victoria and other towns in northern Nuevo León. Their homes have turned into a conflict zone, with hostile cartels vying for control of logistics and shipping corridors. These conflicting developments force the question: What good is an economic boom if the state cannot bring order to it and the result is the deaths and disappearances of children like José Luis Martínez Cruz?

The highways connecting Nuevo León to the U.S. at Laredo, Texas, are among the best selling points the government of Nuevo León has to offer. At the same time, carrier organizations and truck drivers decry the risks they face on the road, from abuse and extortion by authorities to robberies and kidnappings by organized crime (often with the complicity of local police). Jayr Matus, Nuevo León delegate of the Mexican Alliance of Carriers Organization, said his group has urged authorities to do more as its drivers have become a popular target of crime.

“Initially, only cargo was stolen,” Matus told me. “But now it is also the vehicles and the kidnapping of drivers.”

On the Monterrey-Nuevo Laredo highway, dubbed the “highway of terror,” over 70 people disappeared during 2021, according to United Forces for Our Disappeared in Nuevo León, a group that includes families of the missing. Most of the victims were truck drivers carrying goods, or drivers of ride-hailing services. “It seems as if the earth swallowed them, that there is no trace because the authorities do not investigate,” said Angelica Orozco, who joined United Forces for Our Disappeared after a former university classmate vanished in Monterrey during the first years of the war on drugs.

During a visit to Monterrey in September, U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Ken Salazar acknowledged the importance of Nuevo León as a leader in North American supply chain integration. Although local business people have expressed concern about the security situation, Salazar said, companies have chosen Nuevo León for reasons of confidence. But when pressed at a news conference by this reporter, he admitted, “You can’t have integration if these roads are not safe.”

What good is an economic boom if the state cannot bring order to it and the result is the deaths and disappearances of children like José Luis Martínez Cruz?

As part of the state’s efforts to improve transportation infrastructure so that Nuevo León can boast “the fastest and safest border crossing in Mexico,” the state government has unveiled what it calls a Master Road Plan. The governor of Nuevo León, Samuel García, a 35-year-old former senator who came to power in 2021 thanks to the support of his wife’s social media following, promised well-armed detachments of the National Guard and the Fuerza Civil state police to secure exports to the U.S. As Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador further militarizes public security, García also announced the opening of a new military base that would house 600 soldiers in the municipality of Cerralvo to “shield” the border with Tamaulipas. While Tamaulipas faces endless cycles of violence due to disputes between drug cartels, Nuevo León has been considered, until now, a relatively safe state, shielded from drug cartel violence.

After NAFTA, the number of cargo trucks crossing the U.S.-Mexico border increased, while drug trafficking routes became more accessible. But this rapid growth also brought a surge in drug-related violence in many border cities, such as Matamoros or Reynosa in Tamaulipas.

Efrén Sandoval, who investigates informal cross-border trade in northern Nuevo Léon at the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology, explains that the state’s desire to protect certain sectors, in this case investors, implies the presence of new state agents and new security policies on many of these routes that were already under the control of cartels (with the support of some authorities). As trade increases and smuggling routes become more accessible and attractive, but also more heavily monitored, the struggle for control intensifies.

“All of this is nothing more than a control of routes and plazas,” Sandoval added, referencing the regional organizations that control drug trafficking networks.

At least nine other young men disappeared on the same day as José Luis Martínez Cruz. They gradually returned, prosecutors said. (The prosecutor’s office and the local search commission didn’t respond to my request for interviews.) Cruz learned from one of the victims who returned that Martínez Cruz was still alive and being held in a safe house where a criminal group allegedly took the young men. Statements from witnesses indicate that some of them may have undergone forced recruitment.

A recent study published in the journal Science estimates that organized crime is the fifth-largest employer in Mexico, and recruits some 350 new members every week to replace their losses in manpower due to arrests and murders. Many of those do not join voluntarily. Another woman I met whose family has been victimized, Andrea, says she knows who kidnapped her husband in front of their home in downtown Salinas in the early morning hours of Aug. 4. (I’ve changed Andrea’s name to protect her identity, along with the names of other victims.) The prosecutor’s office, Andrea told me, did nothing with the information she provided. Instead, she moved with her five children to a relative’s home in a nearby town, fearing that her husband’s kidnappers would return. Last August alone, 11 people were reported missing in Salinas, according to the National Registry of Disappeared Persons. “But we are many more. I know at least three other women like me,” said Andrea.

Delia, a 53-year-old from the state of Veracruz, moved in 2018 with her two sons to Ciénega de Flores, two miles from Salinas Victoria. She heard that there were many jobs there, with good salaries. “My cousin said that there was a lot of work,” she told me. “First, I brought my oldest son, then my youngest son, Alejandro, who is now missing.”

Twenty-eight-year-old Alejandro disappeared in Ciénega on Dec. 27, 2022. Witnesses said that a pair of men approached him while he was walking down the street and forced him to get in a car. “When everything overwhelms me, I get depressed,” Delia told me. “I have nothing else than to look for my son.”

A recent study published in the journal Science estimates that organized crime is the fifth-largest employer in Mexico, and recruits some 350 new members every week to replace their losses in manpower due to arrests and murders.

Last March, Delia had to quit her job as a wire harness assembler for an industrial refrigeration manufacturer to search for her son and care for Alejandro’s seven-year-old daughter. Delia looked for Alejandro in hospitals, prisons, morgues and on the streets. She found no trace of him. After several months, she was warned of the risks by her neighbors as more and more cases of missing people cropped up. At least 42 people have disappeared in Ciénega this year.

Delia returned to work in August, now for an American company that manufactures drinking water coolers, where she works as a machine operator cutting carbon filters. She works a 12-hour night shift, four days a week, earning $14 a day.

Cruz and Delia feel more and more isolated as authorities fail to attend to their cases. Sometimes, they worry that organized crime members will harm them or other family members, but silence is no longer an option. “They [the authorities] have to do something,” Cruz told me. “At least, keep looking. Give me the body. Do something.”

Local police, however, are sometimes complicit in the disappearances. On October 16, a dozen state and military law officers arrived at the premises of the Secretariat of Public Security in Ciénega de Flores. Six police officers, the secretary of public security, and a judge were arrested and charged with aggravated kidnapping. They were allegedly involved only in two cases that occurred in November 2022 and March 2023. The families of the missing in Ciénega hope that more information will come to light about the relationship between organized crime and state agents in carrying out disappearances.

Some of the victims have been freed from the clutches of the cartels only on the condition that they sell drugs for them. When Delia heard that her neighbor’s nephew was back home, she asked if he had seen Alejandro. The nephew had been kidnapped, held for a month, and then released after being beaten and told that his family would be harmed if he refused to do the cartel’s bidding.

When the neighbor asked him about the fate of Delia’s son, he said he didn’t know and advised her to “be careful.” So now Delia imagines that her son is on a long journey. At least, that’s what she tells her fatherless granddaughter to get through each day.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.