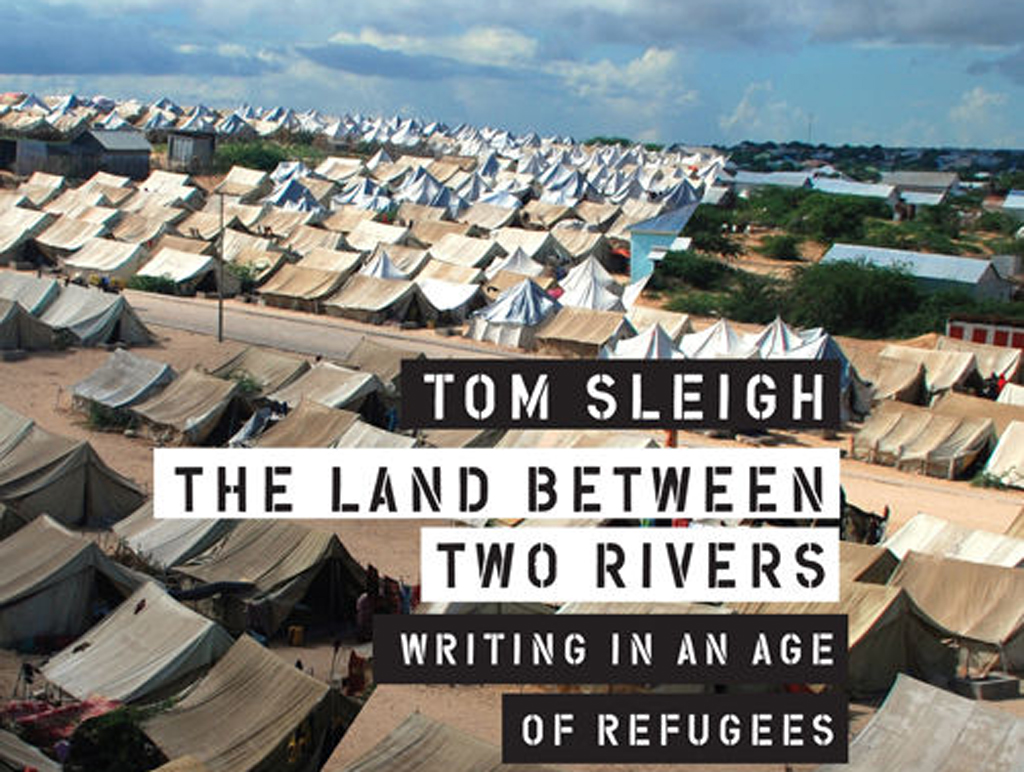

The Land Between Two Rivers

Tom Sleigh travels to war zones and refugee camps, yet views intervention on his part as transgression. When does passivity become complicity? Graywolf Press

Graywolf Press

“The Land Between Two Rivers: Writing in an Age of Refugees”

Purchase in the Truthdig Bazaar

A book by Tom Sleigh

The work of poet and essayist Tom Sleigh is startling in its intensity and passion. So is his heartfelt desire to do good in a cruel world, though he views any sort of direct intervention on his part as a transgression. He is insistent that, even with close, sustained observation, it is impossible to truly understand anyone else’s suffering.

In Sleigh’s new book of essays, “The Land Between Two Rivers: Writing in an Age of Refugees,” he travels to war zones and refugee camps in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Kenya, Somalia and Iraq. When he returns exhausted, his close friends badger him about what he has seen. He feels unable to express the inexpressible, particularly to those who have only experienced Western privileges. He usually chose silence. “So I said to my friend,” Sleigh writes, “that I didn’t know what to do with such feelings and perceptions, they weren’t exactly useful. If people are starving there, they aren’t starving here—or if they are, they aren’t dying in the hundreds of thousands—and news photos of starving kids felt, to me at least, like a kind of cant: PTSD lite, you could call it.” Sleigh has spoken in interviews about feeling as if he often lived in a “hell of abstractions, of media images, of jabbering competing ideologies. … ” When far from home, he confesses he feels a certain exhilaration, a transcendence from his usual preoccupations at home.

Click here to read long excerpts from “The Land Between Two Rivers” at Google Books.

Sleigh never married or had children. He is devoted to his craft, which he practices for hours each day, as he has for the last several decades. He has published nine books of poetry and a previous essay collection, “Interview With a Ghost.” He teaches at Hunter College in New York. He grew up in many different places: Utah, Texas, and eventually California, watching his parents scrabble together a living for their large family. His mother grew up dirt poor in a tiny Kansas town and suffered from bouts of serious mental illness that required shock treatments and hospitalizations. In one of the most moving essays in the book, “Momma’s Boy,” he writes about her with strained affection. He recalls her weaponized voice when her inner demons took control of her, but also the excited, engaged way she read to him when things were better. Sleigh was always an avid reader. His mother taught high school during her more stable periods, and rebelled against her Mormon upbringing by discussing with her students her doubts about God.

Sleigh spent several years doing serious drugs. Not just marijuana, but speed, psychedelics and heroin. The drugs, he felt, gave him access to spiritual sides of himself that were otherwise closed off. He was always a seeker. As a young man he was diagnosed with a serious blood disorder that brought him to death’s door many times over the last few decades. He remembers thinking during one of those episodes that what he would miss most about the world was watching the play of sunlight and shadows on sunflowers. In his writing there is an exhilaration that comes with surviving, but also a darkness and wariness.

His writing can be heartbreaking. He watches a 2-year-old boy in a refugee camp, close to death, take a biscuit from his mother, unwrap it slowly, and nibble. The boy’s eyes opened wide as the life-giving sugar entered his starving body. Sleigh realized at that moment that until we lose consciousness, we remain defiant to the end.

In “To be Incarnational,” he writes about the lives of Somali refugees in East Africa, and the horror of witnessing firsthand a famine that has taken a quarter of a million lives. He writes of mothers forced to make the harrowing decision of which child to save. Which little one can the mother carry in her arms without collapsing herself?

Sleigh rarely speaks about God, but admits to a certain fascination with Jesus, whom he views as a bridge between the human and the divine. Religious piety of any kind does not move him, but poetry does. He is interested in “secularizing the mysteries of death, redemption, and resurrection.” That sensibility ripples throughout this essay collection, as well as his quiet, unyielding resistance to crossing the emotional and psychological boundary from witness to activist.

Sleigh is adamant that this lens of non-interference is the correct one for him, and spends huge portions of the book defending his stance. He writes movingly of Mahmoud Darwish’s meditation on collective suffering and the reality that millions of people live unnoticed lives of despair. He quotes Darwish:

Murdered, and unknown. No forgetfulness

has remembered to forget them, no remembrance

has scattered them to gather them in again.

They lie hidden in winter’s brown weeds in the ditch

beside the two lane highway that runs back and forth

between the two long stories about heroism and suffering.

“I am the victim.” “No, I alone am the victim.”

Sleigh does not want to speak for others, or convince them that their thinking may be flawed or self-defeating. Statistics about human suffering, to him, are useless. Instead, he believes the counterintuitive approach of describing human misery is more powerful. He is drawn to the work of painter and poet David Jones, whose poetry focuses on the trauma of ordinary soldiers in warfare rather than heroism and moral outrage.

Sleigh makes a compelling argument, but there are gaping holes in it. Isn’t there a moral imperative to take a stand? To speak out against racism, sexism, violence and tribal hatred? In trying to change hearts and minds? If every life is sacred and unique as he insists, isn’t his also? Are all judgments about others treacherous? Is it possible they could be helpful? Could confronting someone about their relentless hatred be an act of benevolence?

Many of Sleigh’s stories seem to call for his interference. This one resonated with me: He was speaking with a man near Quneitra, a Syrian town in the Golan Heights. The man was releasing an avalanche of grievances about the Israelis, and Sleigh felt his chest tighten a bit as the man’s rhetoric became more inflammatory. The man told Sleigh he loved the Arab Jews, whom he felt were blood brothers of a sort, but insisted that the colonial European Jews needed to return to Europe. He equated these Jews with Nazis and pledged that he would resist them until “the last drop of blood” is shed. Sleigh said nothing. Where is the nobility in that? When does Sleigh’s excessive silence become an unintentional complicity that Sleigh himself would find unacceptable?

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.