Donald Trump held an iftar dinner to break fast with Muslims on Wednesday. His guests, however, were not American Muslims but rather a select number of ambassadors to the U.S. from pro-American Muslim governments.

A survey of the Arabic press shows that this nuance is being ignored by the headline writers, who report that Trump invited “American Muslims.” He did not, since most would have declined the invitation. As it was, there were several alternative iftar dinner protests by Muslims against Trump. In other cases, as with [the Muslim Public Affairs Council], prominent Muslim-American organizations were not invited.

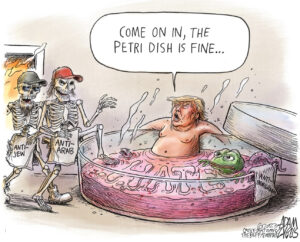

It is being speculated that the event is a form of Islam-washing, i.e., of pretending to be tolerant toward Muslims via a public spectacle while actually despising Muslims. Trump has said so many negative things about Muslims that the about-face is hard to understand.

Why would Trump engage in Islam-washing? Because his ban on visas for Muslims from five countries is before the Supreme Court, having been challenged by Derek Watson, a federal district judge in Hawaii. I explained when Watson made his ruling: “Watson finds that the [executive order] targets six countries with a Muslim population of between 90 percent and 97 percent and so obviously primarily targets Muslims.”

The [Jeff] Sessions Department of Justice argued that the language of the law is religiously neutral and so there is no violation of the Establishment Clause “facially” (i.e., if you just look at the language of the order).

Judge Watson shows that it is permitted to take into account the intent of a law when there is a question of it violating the Establishment Clause:

“It is well established that evidence of purpose beyond the face of the challenged law may be considered in evaluating Establishment and Equal Protection Clause claims.” (citing Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520, 534 (1993): “Official action that targets religious conduct for distinctive treatment cannot be shielded by mere compliance with the requirement of facial neutrality.”)

Those legal scholars who argue that it is not permitted to take into account the legislative history of a law or regulation, but that the “facial” language of the law should be determinative don’t seem to know as much case law as Judge Watson.

The judge then goes on to cite the many statements by Trump showing that he has an animus against Muslims, and that animus underlies his executive order banning everyone from six Muslim-majority countries.”

This issue of whether intent can be taken into account has just heated up because of the recent ruling, authored by centrist swing vote caster Justice Anthony Kennedy, that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had shown hostility rather than neutrality toward the faith principles of the baker who declined to make a wedding cake for a gay wedding.

Kennedy did not deny the principle that religious faith cannot be used as a pretext to damage the rights of a protected class of persons. An old-school Mormon who thought African-Americans bear the mark of Cain could not refuse to serve them in his restaurant, for example.

All Kennedy was saying was that the adjudicating authority has to exercise neutrality rather than hostility toward religious principles.

That is, Kennedy just openly accepted that the “legislative history” of a decision like that of the Colorado Human Rights Commission with regard to the evangelical baker is crucial to deciding whether his rights were injured.

And that is what Judge Watson in Hawaii argued with regard to Trump’s Muslim ban.

So you could imagine Trump aides like Rudy Giuliani urging Trump to reverse his decision of last year to stop holding iftar dinners during the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan. His reversal of this tradition, which goes back to the Clinton era (and in some ways all the way back to Thomas Jefferson), had underlined Trump’s hostility to Muslims, which he has expressed publicly on numerous occasions.

Federal attorneys arguing for the Muslim ban will need to have something to say when the other side brings up Trump’s bigotry in tracing the legislative intent of the Muslim ban.

Giuliani admitted that claiming a national security threat was just a legal pretext for keeping Muslims out.

So the holding of the iftar dinner is designed to offer a different image of Trump that could cast doubt on the conclusion that Islamophobia lay behind the Muslim ban.

Some of the countries whose representatives attended have been extremely obsequious toward Trump’s Muslim ban. This is true of Saudi Arabia, which applauded Trump’s visa ban. After all, its wealthy royals can come and go as they please—who cares about some Syrian refugees? (Trump has kept out almost all Syrian refugees this year).

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.