Insurrection and the Hypocrisy of Originalism

The Supreme Court is about to green light Donald Trump’s run for a second term. President Donald Trump and Amy Coney Barrett stand on the Blue Room Balcony after Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas administered the Constitutional Oath to her on the South Lawn of the White House White House in Washington, Monday, Oct. 26, 2020. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

President Donald Trump and Amy Coney Barrett stand on the Blue Room Balcony after Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas administered the Constitutional Oath to her on the South Lawn of the White House White House in Washington, Monday, Oct. 26, 2020. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

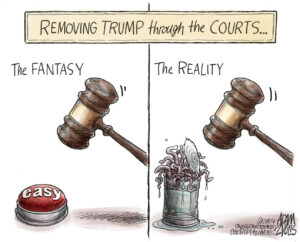

Although oral arguments before the Supreme Court can sometimes be difficult to decipher, I am willing to make a prediction: There is no way the court is going to boot Donald Trump from the presidential ballot. Despite the plain meaning of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which bans insurrectionists from holding public office, the court made its position clear during the arguments it heard on Feb. 8 in Trump v. Anderson. The former president’s central role in inciting the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol seemed to matter little, if at all, to any of the justices.

This should come as no surprise. The court, after all, is dominated by hard-right Republican appointees, including three named to the bench by Trump himself. It is noteworthy, however, that the justices signaled a willingness to abandon their favorite theory of constitutional interpretation — originalism — to reach the desired result of saving Trump’s candidacy.

The Supreme Court is tasked in Anderson with reviewing the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision, issued last December, that disqualified Trump from appearing on that state’s presidential primary ballot. The Colorado court’s opinion is a meticulously reasoned 213 pages log. It also adheres closely to the principles of originalism — the idea that the terms and provisions of the Constitution and its amendments must be understood today as they were understood at the time they were adopted.

Section 3 of the 14th Amendment provides:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any state legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any state, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

As originalism requires, the Colorado court engaged in a detailed analysis of both the text and history of Section 3. For purposes of the Jan. 6 attack, it defined “insurrection” as “a concerted and public use of force or threat of force by a group of people to hinder or prevent the U.S. government from taking the actions necessary to accomplish a peaceful transfer of power in this country.”

On the issue of whether Trump personally engaged in insurrection on Jan. 6, the Colorado court held:

[T]he record amply demonstrates that President Trump fully intended to—and did—aid or further the insurrectionists’ common unlawful purpose of preventing the peaceful transfer of power… He exhorted them to fight to prevent the certification of the 2020 presidential election. He personally took action to try to stop the certification. And for many hours, he and his supporters succeeded in halting that process.

On the question of whether presidents are “officers” of the United States within the section’s meaning, the Colorado court concluded:

[T]he plain meaning of “office . . . under the United States” includes the Presidency; it follows then that the President is an “officer of the United States… Indeed, Americans have referred to the President as an ‘officer’ from the days of the founding… Section Three’s drafters and their contemporaries understood the President as an officer of the United States.

One of the purported selling points of originalism is that it minimizes judicial bias and subjectivity by requiring judges to stick to the law regardless of the practical consequences of their decisions. True to that precept, the Colorado court explained:

We do not reach these conclusions lightly. We are mindful of the magnitude and weight of the questions now before us. We are likewise mindful of our solemn duty to apply the law, without fear or favor, and without being swayed by public reaction to the decisions that the law mandates we reach.

By contrast, on Feb. 8, the justices of the United States Supreme Court seemed eager to discard originalism along with their solemn duties as neutral stewards of the law. About a third of the way through the two-hour proceeding, Justice Neil Gorsuch asked Trump’s lead attorney, former Texas Solicitor General Jonathan F. Mitchell, “Is there anything in the original drafting, history, discussion [of the 14th Amendment] that you think illuminates [how Section 3 should be read]?”

Mitchell responded, “[W]e aren’t relying necessarily on the thought processes of the people who drafted these provisions because they’re unknowable. But, even if they were knowable, we’re not sure they would be relevant.”

What seemed to concern the court far more than originalism were the messy consequences that could flow from a ruling against Trump.

This was a remarkable concession about the limitations of originalism as an all-purpose legal philosophy. But no matter. What seemed to concern the court far more than originalism were the messy consequences that could flow from a ruling against Trump.

“The consequences of what the Colorado Supreme Court did, some people claim, would be quite severe,” mused Justice Samuel Alito, suggesting that electoral chaos would ensue as some states followed Colorado’s lead and others issued contrary rulings. Echoing Alito’s anxieties, Chief Justice John Roberts observed, “If Colorado’s position is upheld, surely there will be 10 disqualification proceedings on the other side. And some of those will succeed.”

There is nothing inherently wrong or unusual with considering consequences. Although originalists deny it, they do it all the time. Over the past two decades, the Supreme Court’s originalists have pursued a right-wing agenda with dire practical consequences in a series of transformational rulings on voting rights, gerrymandering, union organizing, the death penalty, environmental protection, gun control, abortion, campaign finance, affirmative action and more.

The problem for the court in Anderson is that a faithful application of originalism would require a decision disqualifying Trump from holding future office not only in Colorado, but across the entire nation. Attorney Jason Murray, who helped file the initial lawsuit against Trump last year, crystalized the issue in the waning minutes of the Feb. 8 hearing, remarking:

The Framers of Section 3 knew from painful experience that those who had violently broken their oaths to the Constitution couldn’t be trusted to hold power again because they could dismantle our constitutional democracy from within, and so they created a democratic safety valve… [T]his case illustrates the danger of refusing to apply Section 3 as written because the reason we’re here is that President Trump tried to disenfranchise 80 million Americans who voted against him. And the Constitution doesn’t require that he be given another chance.

If judicial decorum had permitted, Murray might have taken the next logical step and called out the justices for the hypocrites they undoubtedly are.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

I truly hope you are incorrect.