In Boston Bombing Trial, Winners and Losers Are Hard to Tell Apart

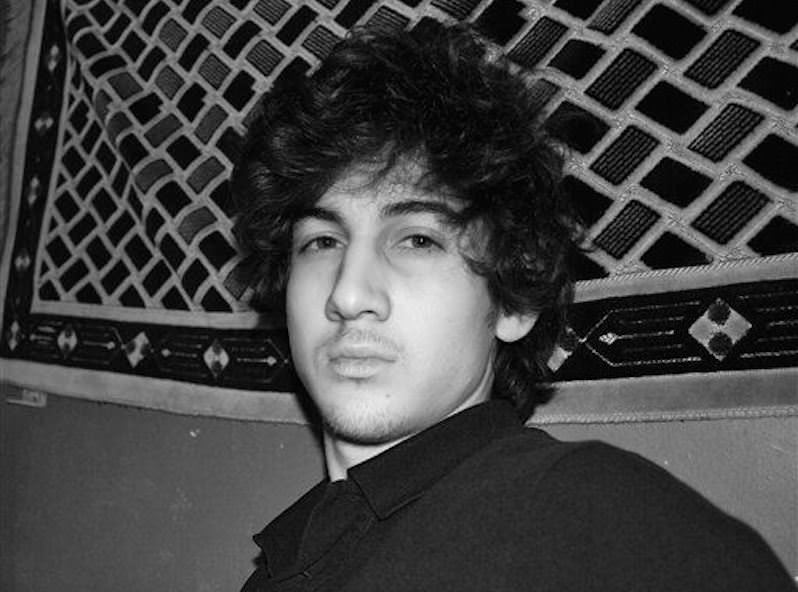

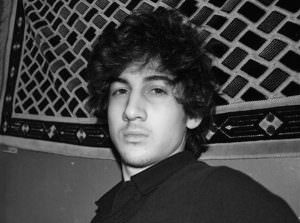

To a nation riveted by the televised trials of OJ Simpson and Casey Anthony, following a life-or-death courtroom drama with no cameras is proving to be a nail-biterTo a nation riveted by the TV trials of O Simpson and Casey Anthony, following a life-or-death court drama with no cameras is a nail-biter. Wikimedia Commons / Voice of America

Wikimedia Commons / Voice of America

If you are at all interested in criminal justice, chances are that at one point or another, you’ve tuned in to watch televised coverage of the nation’s biggest trials. From O.J. Simpson and the Menendez brothers in the mid-’90s to Casey Anthony and Jodi Arias in the ’10s, watching high-profile, high-stakes trials has become a lurid national pastime, offering us the melodrama of afternoon soap operas combined with the suspense and spectacle of major sporting events.

We like to tune in to get our daily fixes — to see how the defendants are holding up; how the lawyers are conducting their direct and cross-examinations; and how the news anchors and expert commentators like HLN’s fiercely pro-prosecution Nancy Grace and CNN’s more measured, pro-defense Mark Geragos are handicapping the evolving courtroom events. Tuning in is how we keep up and how we assess who is winning. Above all, it is how we experience a vicarious sense of justice or outrage, depending on our particular viewpoints and the ultimate outcomes.

Consequently, you might have been feeling frustrated in your efforts to stay abreast of the developments in the trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the accused Boston Marathon bomber. You might have even found yourself asking: Which side is winning?

But as a federal proceeding, the trial, which began March 4, is not being televised. In fact, federal trials prohibit even the use of still cameras.

To complicate matters further, unless your last name is Koch, Bloomberg or Adelson, chances are you can’t afford to buy a personal copy of the Tsarnaev trial transcripts. With a price tag of $6.05 per page — assuming the trial will be about 68 days in length — the price for the first complete rush transcript could easily top $92,000, roughly equivalent to the bill you’d pay for five gold Apple Watches. (The price drops to a still-expensive $1.20 per page for the second and subsequent transcripts sold; and in case you’re wondering, there’s no app available to help with access or to expedite download time.)

Absent both TV and transcripts, we are being forced to follow the ebbs and flows of the Tsarnaev case the old-fashioned way — through the daily accounts and impressions of the handful of reporters who have been allowed inside the courtroom in which the 21-year-old defendant is facing the death penalty.

This is what we know so far:

For his alleged role in the April 15, 2013, bombing that killed three people and injured more than 260 and for the fatal shooting of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology police officer, Tsarnaev was named in a 30-count indictment accusing him of: using weapons of mass destruction resulting in death; bombing a public place; conspiracy; and carjacking. In January 2014, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that the Department of Justice would seek the death penalty if Tsarnaev is convicted.

However, Massachusetts — where the trial is taking place after defense motions for a change of venue were denied — is one of 18 states that have abolished capital punishment. Thus, the case is being tried as a purely federal one; parallel state proceedings have been stayed.

But Tsarnaev still has a good chance of avoiding a death sentence.

Under the Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994 and its 1988 predecessor, federal prosecutors have tried 229 capital cases before juries, securing 79 death sentences (for a rate of 34 percent). To date, a mere three of those condemned to die have been executed at the United States Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Ind. — all by lethal injection. The first to die, in June 2001, was the Oklahoma City bomber, Timothy McVeigh; the second, eight days later, was the drug kingpin Juan Raul Garza; and the last, in March 2003, was the Gulf War veteran and convicted murderer Louis Jones Jr.

Tsarnaev’s defense team also includes some of the country’s most prominent death-penalty lawyers, including Washington and Lee University law professor David Bruck; the chief federal public defender for Massachusetts, Miriam Conrad; and the renowned Judy Clarke.

Clarke’s past clients include Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber; Susan Smith, the South Carolina mother who drowned her two children; Eric Rudolph, the Atlanta Olympics bomber; and Jared Loughner, who shot and killed six people and severely injured a former Arizona congresswoman, Gabby Giffords, at a Tucson community meeting. All those defendants were spared the death penalty, and all but Smith worked out pretrial plea bargains for life sentences.

No such plea bargain, however, was offered to Tsarnaev.

Though Holder, the attorney general, has announced his support for a national death-penalty moratorium while the United States Supreme Court reviews the constitutionality of lethal injection and though he personally views the use of the death penalty as unwise, he has instructed his deputies to proceed full speed ahead with Tsarnaev’s prosecution. The government’s strategy, as the indictment and the first two weeks of trial testimony make clear, is to portray the defendant as a militant jihadist who, along with his older brother Tamerlan, was determined to kill as many Americans as possible.Confronted by a mountain of evidence against their client and unable to secure a plea bargain, the defense team was forced to make a crucial decision: either fight each and every one of the 30 charges tooth and nail in the hope of establishing reasonable doubt about one or two (thereby risking alienating some jurors with contentions that those jurors might later deem false), or admit Tsarnaev’s participation in the crimes and prepare the groundwork for the penalty phase of the trial. To the surprise of many observers — including, most significantly, the prosecution — the defense chose the latter option.

“It was him,” Clarke told the jury on the first day of trial, acknowledging the horror of the bombing and conveying her deepest sympathies to her client’s victims. The real question, she suggested, is not whether Dzhokhar Tsarnaev participated in the carnage but whether he had been led astray by his overbearing sibling, Tamerlan.

From a legal standpoint, the strategy was pure brilliance.

Under the rules of “guided discretion” — the name given to the version of capital punishment that the Supreme Court’s 1976 Gregg v. Georgia decision ruled constitutional — juries must balance and weigh specified aggravating and mitigating factors, including the charged offense and the defendant’s background and character, to determine whether a defendant, if convicted, should live or die.

In the federal system, aggravating factors might include prior felony convictions or a determination that the offense presently charged was committed in a “heinous, cruel or depraved” manner. For Tsarnaev, mitigating factors might include his young age at the time of the offense, the absence of a prior criminal record and whether he acted under duress, suffered from a severe mental or emotional disturbance or was a relatively minor participant in the charged crime.

Under the Federal Death Penalty Act, the government will have the burden of proving any aggravating factors beyond a reasonable doubt. Tsarnaev, by contrast, will be required to prove mitigating circumstances only by a preponderance of the evidence, a far more lenient standard.

The real action in the trial thus has yet to unfold. When it does — after guilty verdicts on all or the overwhelming majority of the alleged charges have been returned — the jury will already have heard and digested the most damning and demonizing evidence against Tsarnaev.

The penalty phase will be Clarke’s and her colleagues’ time to humanize Tsarnaev with testimony from his friends and family, teachers and mental health experts. The closing argument will be this or some variant of this: No matter how many people died and were maimed in the marathon bombing, nothing of value, no moral closure, no deterrence of others will be achieved by yet another senseless execution.

Given the DOJ’s anemic track record in death-penalty trials since 1988, the odds favor a life sentence for Tsarnaev. But even if the government overcomes those odds at trial, the case will be far from over. Years of appeals will lie ahead.

In addition, in May 2014, following a horrendously botched lethal injection in Oklahoma, President Obama ordered a high-level policy review of how the death penalty is applied in the United States today. This April, the Supreme Court is expected to hear oral arguments in a case that will test the constitutionality of Oklahoma’s lethal injection protocol.

Once seen as the most humane of all execution methods, lethal injection has proved to be as cruel and unusual as the rest. Even several large pharmaceutical manufacturers have climbed off the death-penalty bandwagon, refusing to supply prisons with the drugs needed for the deadly cocktails used to carry out executions.

Who then, so far, is winning the trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev?

The best answer may be that no one is — and that no one can. From any rational perspective, all involved are losers: the victims whose lives were taken; the many who were injured and survived; the Department of Justice, which is advocating an archaic and barbaric remedy; and, of course, the defendant, who will either follow the footsteps of Timothy McVeigh into the Terre Haute death chamber or spend the rest of his natural life behind bars.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.