Hungrier Insects Will Bite Into World’s Crops

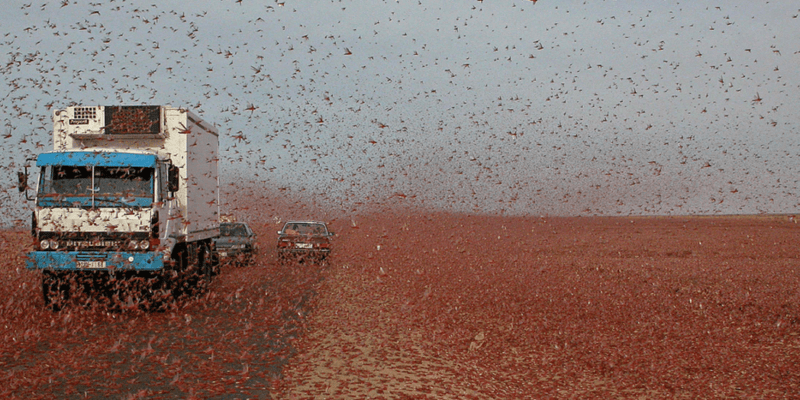

Higher temperatures mean hungrier insects. And that will mean more crop losses. The question is: Who loses most? Desert locusts in Morocco. (Magnus Ullman / Wikimedia Commons)

Desert locusts in Morocco. (Magnus Ullman / Wikimedia Commons)

Researchers have confirmed, once again, that a warmer world is likely to have hungrier insects. The new predators could increase their share of the harvest of wheat, rice and maize by up to 25%.

That is, for every 1°C rise in average temperature, aphids, beetles, borers, caterpillars and other crop pests could increase their consumption of grain by between one tenth and one quarter.

And with a 2°C rise above the average temperature for most of human history – the target set by 195 nations in Paris in 2015 – additional global losses of grain to insect pests could reach 213 million tonnes a year.

For once, the steepest losses could be experienced in the temperate zones, home to the richest nations, rather than in the poorest communities. The reasoning is simple, and the scientists spell it out with a clarity not normally found in scientific prose.

“Our choice now is not whether or not we will allow warming to occur, but how much warming we are willing to tolerate.”

“First, an individual insect’s metabolic rate accelerates with temperature, and an insect’s rate of food consumption must rise accordingly,” they write.

“Second, the number of insects will change, because population growth rates also vary with temperature.” And for that reason, insect numbers in the tropics might decline, but pest numbers in the cooler regions will rise.

Curtis Deutsch of the University of Washington in Seattle and colleagues report in the journal Science that they set themselves the challenge of calculating potential crop losses to insect pests in a warmer world.

They took what is already known about 38 insect species from different latitudes, and the data for harvests over recent decades. About one third of all crops are lost to pests, diseases and weed competition: the point of the study was to isolate the impact of insect predation under a scenario of global warming.

Tropical impact lessened

Most crops are lost in the tropics, but the extra appetite in tropical pests could be offset by reduced numbers as the thermometer rises.

France, China and the US – the countries that produce most of the world’s maize – could experience the most dramatic crop losses from insect pests. France produces much of the world’s wheat, China much of its rice: both crops will be hit hard.

Altogether the scientists calculate that with a 2°C rise – and average global temperatures have already risen by about 1°C – by 2050 the median increase in losses of yield across all climates could be 46% for wheat, 19% for rice and 31% for maize: all of it to ever-hungrier caterpillars, beetles and borers.

These percentages translate to 59 million tonnes for wheat, 92 million tonnes for rice and 63 million tonnes for maize.

Food security jeopardised

Such research is a fresh iteration of an increasingly familiar theme: the threat to food security in a world of climate change driven by ever-increasing use of fossil fuels to raise greenhouse gas ratios in the atmosphere to unprecedented levels. Insect predation however is not the only factor.

Repeatedly over the last decade, researchers have warned that higher levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide could affect the levels of protein, iron and zinc delivered by crop plants; that the greater extremes of heat that must accompany higher average temperatures could hit grain harvests and yields of fruit and vegetables.

Rice, wheat and maize between them provide a huge share of the world’s calorie intake. The three grains are staples for about 4 billion people, and the UN calculates that more than 800 million worldwide do not have enough to eat.

Most of these are in the developing world, and in the tropics. The twist in the latest research is that it predicts that the biggest losses will be in the well-off zones.

Guiding policy

Eleven European countries are expected to experience a 75% increase in insect-linked wheat losses: altogether, by 2050, insects could be consuming 16 million tonnes of wheat. The US could see a 40% increase in maize losses to pests, and farmers will lose 20 million tonnes in yield. Rice losses in China alone could reach 27 million tonnes.

Such studies are intended as a guide to help ministries of agriculture, crop research institutions and other national and civic governments to confront a future of climate change.

Crop scientists could start devising new farming strategies, and working on more resistant crop varieties. Nations could begin to deliver on promises to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“I hope our results demonstrate the importance of collecting more data on how pests will impact crop losses in a warming world,” said Dr Deutsch, “because collectively, our choice now is not whether or not we will allow warming to occur, but how much warming we are willing to tolerate.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.