How the Media Upholds Climate Crimes

Mainstream outlets bolster the legitimacy of state and corporate climate violence through decontextualizing protesters’ actions and privileging false ideas of objectivity. Climate activists are arrested as they blockade the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to call for an end to the use of fossil fuels, Monday, Sept. 18, 2023, in New York. (AP Photo/Jason DeCrow)

Climate activists are arrested as they blockade the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to call for an end to the use of fossil fuels, Monday, Sept. 18, 2023, in New York. (AP Photo/Jason DeCrow)

A climate protester named Mama Julz spent February 1 locked to a grounded helicopter, the kind usually used to transport construction workers to remote portions of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, the rushed and ecologically destructive pet project of West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin. After a few hours, police arrested Mama Julz and one other protester who supported the nonviolent direct action. Both were charged with a misdemeanor and held in jail without bond.

Later in February—and 470 miles south of the planned route for the Mountain Valley Pipeline—local, state, and federal law enforcement raided the homes of three activists for their involvement in protesting the Weelaunee Forest’s development into a $110 million police training center known as Cop City. Police dragged one person out by their hair and forced another to sit topless for hours in the back of a police car. Despite the nonviolent nature of the protests and the outsized police response, both stories received little coverage.

For climate activists, the connection between police and the ever unfolding climate crisis is exceedingly evident. Since 2016, both public and private police forces have cast themselves in key roles suppressing and surveilling climate protests at Standing Rock, at Line 3 camps in northern Minnesota, and all along the route for the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Violence from police arguably reached its height of impunity in Atlanta, where officers at a Stop Cop City encampment killed 26-year-old forest protector Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán in January of last year. No police have been charged in the killing, and law enforcement’s response to Cop City protests have only continued to escalate. Before the recent raids in February, state patrol also raided the houses of Cop City bail fund organizers last year and later charged them with racketeering.

For climate activists, the message is clear: wherever there are climate protests, police soon follow.

By neglecting to call attention to the connections between climate protests and police violence, journalism helps to produce the conditions of climate criminality.

This connection is one that journalism fails to draw or, when it does, fails to question. Whether born of ignorance or fealty to institutions, the mainstream media’s silence on the criminalization of climate protest has helped to engender broad public acceptance of government-vested corporate power and violent police treatment against climate protesters. Perhaps most alarmingly, the media’s silence has also helped to usher in a wave of anti-protest laws that stifle dissent.

“There are massive, entrenched interests in retaining the kinds of economic arrangements that are at the heart of pumping more carbon into the atmosphere,” said Alex Vitale, a sociology professor at Brooklyn College. “Those interests are extremely powerful and unfortunately appear to be prepared to fight to the death of all of us in order to maintain their advantage.”

By neglecting to call attention to the connections between climate protests and police violence, journalism helps to produce the conditions of climate criminality—or the belief that climate protesters are immoral and worthy of suppression.

Media has a problem

About 70,000 people marched in New York City in September of last year to demand the Biden administration address the ballooning climate crisis. Throughout the week, activists blockaded banks that insure pipelines and protested against federal support of extraction on public lands. At rallies, attendees also heard from community organizers like Sharon Lavigne, who lives in a heavily polluted petrochemical corridor in southern Louisiana. The message of the protests was clear: The U.S. produces a disproportionate amount of climate change-causing fossil fuels. And if climate change is a threat to global public health, then the solution is to end fossil fuel consumption.

Mainstream media lost the plot. Journalists spent lengthy word counts on sensational descriptions of protesters and middling descriptions of ambitious and science-backed demands for a transition away from fossil fuels. Many of them placed the police responses to protests in the first third of the article. The implied message to readers was that climate activists are unserious, the government must navigate onerous legal red tape regarding resource extraction on public lands, and police were necessary to quell any wrongdoing in Manhattan.

Journalists spent lengthy word counts on sensational descriptions of protesters and middling descriptions of ambitious and science-backed demands for a transition away from fossil fuels.

Take, for example, a Washington Post article co-written by Timothy Puko and Dino Grandoni that opened with the line, “They arrived by the thousands, wearing gas masks and melting-snowmen costumes and carrying signs calling for an end of burning fossil fuels.” The activists’ demand, the authors argued, was “to do more to combat climate change.” The next sentence listed how many protesters were arrested for blocking an entrance to the Federal Reserve building.

Evlondo Cooper, a senior writer for the climate and energy program at the research nonprofit Media Matters, explained that the Washington Post article was part of a bigger trend in media in which the news is decontextualized from itself. For example, the media might discuss how oil production has hit record highs under Biden’s watch, and on the same day, the same publication will publish a story about the administration’s proposal to protect old growth forests as a climate change-mitigation strategy. “But they never connect those stories,” Cooper said.

By siloing these stories away from one another and neglecting their connections and contradictions—and by never seeming to question what the White House stands to politically gain from offering the appearance of a “green” agenda—newsrooms fail to accurately report on and help readers understand the depth and breadth of the climate crisis.

These failures are entrenched in the work. “U.S. media have a history of covering the incremental at the expense of the immense and of coddling rather than confronting corporate power,” wrote Mark Hertsgaard and Kyle Pope, founders of Covering Climate Now, for Columbia Journalism Review. “Without a serious and immediate correction, the press will continue down the same path with climate change, except this time the implications are exponentially greater. Surely, it can do better.”

As another example of how we can do better, take The New Republic’s coverage of the events of Climate Week 2023. A few thousand words were spent processing the tactics of Climate Defiance, grassroots direct action organization. The article questions if time might be better used making friends with the Biden administration than demanding climate accountability from it. Scene-setting paragraphs recount how Climate Defiance organizers interrupted public speeches by White House Climate Adviser Ali Zaidi in an attempt to “bird-dog”—aka hound at every point possible—the official. Organizers demanded answers as to why Biden approved ConocoPhillips’ Willow Project, a proposal to drill for oil in Alaska that some activists have dubbed a “carbon bomb.”

Implicit in this foregrounding of Climate Defiance’s tactics was a question of civility: Is it polite to interrupt people in power? Under the guise of evaluating the organization’s choice of direct action to achieve policy changes, the writer questions the value of the activism itself rather than the hypocrisy of the administration that invited the interruptions in the first place.

“We’re interested in procedural discourse at the expense of being able to identify real misbehavior, which is companies lying [and] government leaders being uninterested in holding them accountable for doing so,” said Andrew McCormick, deputy director of Covering Climate Now, in an interview with Prism.

What’s possibly more concerning is the extent to which the journalist focuses his scope on the misbehavior of activists—whose job, some might say, is to use misbehavior to shake systems from their slumber and help the public see more clearly—rather than on the misbehavior of those who govern. Media often shields Democrats from accountability for climate misbehavior while unfailingly clinging to the notion that Biden is the “climate president.” Or else, liberal corporate media affirms that Biden is a favorable option to the alternative in Republican candidate and former president Donald Trump. At least Biden believes climate change is happening, the articles suggest. As if that was the baseline.

Media often shields Democrats from accountability for climate misbehavior while unfailingly clinging to the notion that Biden is the “climate president.”

It’s not just the “process stories”—as McCormick calls them—where media undermines or ignores activism as newsworthy. It’s also in coverage of direct action protests like those from Just Stop Oil and Restore Wetlands, where activists threw soup on Vincent van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” painting and smeared paint on Claude Monet’s “The Artist’s Garden at Giverny.” It’s clear the journalists who report on these actions disregard them as absurd, or they otherwise spend their word counts picking the protests apart. Often, coverage places more of an emphasis on responses from museum leadership and police rather than discussing activists’ motivations for taking direct action. The silence speaks volumes, according to McCormick.

“By failing to cover activists as newsmakers, I think we fail to accurately cover the current state of climate discourse,” said McCormick, who added that this kind of coverage positions the protest as more objectionable than the cause, where the public discourse concerns “the incivility of tomato soup [over] the incivility of global inequality.”

Dissent

Corporate media ignores why climate activists actually take to the streets: government subsidies, permits, and leases for fossil fuel operations; inaction that perpetuates existing inequalities or creates new ones; and doublespeak spun to look like environmental justice while the opposite is greenlit behind closed doors.

“They skip past the very real concerns that bring people to the street,” said Media Matters’ Cooper.

Climate science is sounding the alarm bells even if government officials and mainstream media won’t. According to Media Matters, the 2023 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, which warned that the world needs to halve all greenhouse gas and carbon emissions by 2030, resulted in just 14 minutes of broadcast coverage across cable channels. CBS and Fox neglected to report on it at all. The lack of coverage no longer reflects what most Americans believe to be true: According to the Yale Program on Climate Communications, 58% of adults believe that global warming is already harming U.S. residents, and 54% believe the president should do more to address it.

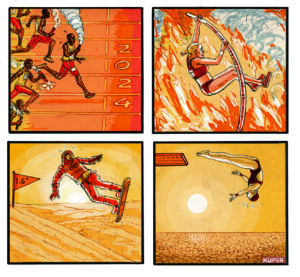

But even with a desire for change, the reality remains that there are few ways the public can push those in power to take action. Adult citizens can vote, lobbyists can impact policy, and anyone with standing can bring a lawsuit against public entities and corporations. Direct actions that take place outside of these venues are often demonized by the media.

In a conversation between New York Times columnist David Marchese and the author of “How to Blow Up a Pipeline,” Andreas Malm, Marchese noted that in representative democracies like ours, “certain liberties” are respected.

“We vote for the policies and the people we want to represent us,” Marchese said. “And if we don’t get the things we want, it doesn’t give us license to then say, ‘We’re now engaging in destructive behavior.’”

“They skip past the very real concerns that bring people to the street,” said Media Matters’ Cooper.

Malm, who engages in direct action to protest climate negligence, of course disagrees. What the Times columnist elides in his question is that opportunities for democratic participation on climate issues have been withheld from the public. In some cases, the opportunities never existed. There are plenty of recent examples to draw from.

In 2022, a federal judge ruled that the Canadian energy firm Enbridge Inc. illegally trespassed on sovereign Native land to continue construction of the Line 5 oil and gas pipeline on the Bad River reservation, yet the company faced almost no consequences. Work on the pipeline continues today. Last year, the Biden administration weakened the National Environmental Policy Act to push through approvals for the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Also in 2023, Atlanta organizers collected more than 100,000 signatures for a referendum on the construction of Cop City that would decimate the Weelaunee Forest, though officials have refused to put the measure on the ballot. There are countless other instances in which democratic routes proved ineffective for changing the course of climate change.

When voters cannot impact public policy through formal means of civic engagement, it reveals how strongly connected climate change is with the health of American democracy—a connection most media ignores. It also shows that climate protests and direct action are some of the last remaining ways to be heard. However, the mainstream largely disregards these protests.

“Truly, how many ways can young people ask for action? How many ways can they ask to be cared about?” McCormick said. “And when there’s no response, and when a response is deserved, what options are left but to find creative ways to garner attention? They’re not hurting people.”

Responses to dissent

In 2016 after a successful campaign by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe to cancel a permit that would have allowed the Dakota Access Pipeline to cross under the Missouri River, the fossil fuel industry got to work ensuring a similar loss wouldn’t happen again. Chemical manufacturers, electric utilities (and their lobbyists), refinery corporations, and gas utility companies partnered with the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and the American Fuel and Petrochemicals Manufacturers to strongarm favorable bills through state legislatures to “protect” so-called “critical infrastructure.”

Since 2017, state legislatures have introduced 270 bills that criminalize or demand harsher penalties for protest, such as raising the minimum charge for trespassing on private property from a misdemeanor to a felony. One bill enacted in Tennessee in 2020 allows prosecutors to punish those who block streets with up to one year in jail. Another bill, enacted by Iowa’s legislature in 2021, provides immunity from civil liability to drivers who injure or kill someone protesting. A map that tracks anti-protest bills illustrates how states with fossil fuel infrastructure like pipelines, refineries, and export terminals have the most of these kinds of laws. In 2021, police associations and private prison companies contributed $343,602 to the sponsors of anti-protest legislation, according to Greenpeace research. That same year, 100 companies contributed more than $5 million to support the passage of anti-protest bills.

If altering state laws wasn’t enough, the fossil fuel industry has filed lawsuits against environmental organizations and collectives. In 2023, the companies behind the Mountain Valley Pipeline filed what’s known as a SLAPP suit—a strategic lawsuit against public participation—targeting organizers in retaliation for direct action protests that halted their construction work. For the past seven years, Greenpeace has been fighting a similar civil lawsuit brought by the company Energy Transfer. The company behind the Dakota Access Pipeline is seeking $300 million in damages.

According to Deepa Padmanabha, deputy general counsel for Greenpeace, it’s not the money these corporations are after. “What they’re essentially trying to do in this lawsuit is create this new theory of law where if you have any involvement in any kind of protests, you can be held liable for the actions of anybody that protests,” Padmanabha said. “It’s really disturbing. What’s at stake is so much bigger than Greenpeace.”

Since 2017, state legislatures have introduced 270 bills that criminalize or demand harsher penalties for protest.

But the federal government beat the fossil fuel industry to it, redefining climate civil disobedience, protest, and direct action as violent crime back in 2012. According to an investigation by Grist and Type Investigations, the Federal Bureau of Investigation opened a “counterterrorism assessment” against Indigenous water protectors in 2012, years before pipeline construction even began. By doing so, the federal agency transformed protest against a privately owned pipeline into an effort to undermine the American government. According to documents Grist obtained as part of the investigation, the pipeline company had “direct access to the White House.”

The documents referred to water protectors as “environmental extremists,” and while federal agents acknowledged that Indigenous peoples and tribes were “engaging in constitutionally protected activity” that included attending public hearings, they also “emphasized that this sort of civic participation might spawn criminal activity.” These documents provide insight into how the government thinks of climate protests, namely that activism isn’t terrorism, but it can be defined as such in the future. Thus is the case for thwarting “illegal” behavior before it becomes illegal and, more importantly, justifying the suppression of speech even if it’s constitutionally protected.

Despite ample evidence of the ways that the fossil fuel industry collaborates with the police to surveil, intimidate, and criminalize protesters, mainstream media continues to display an implicit trust in narratives from law enforcement. Often, police are incorrectly vaunted by the media as experts in safety, said Vitale, the Brooklyn College professor. Rather than enforcing the law, police exist to enforce order—and as far as police are concerned, protests are the ultimate site of disorder.

This means that even if a protester isn’t doing anything illegal, police are empowered by the media to make arrests or respond violently to nonviolent acts of civil disobedience. So much so, Vitale said, that “we’ve built up the power and public legitimacy of police to behave in an unquestioned manner.”

The public and the media’s implicit trust in the police and their role within the criminal legal system appeared to wane in the summer of 2020 after a white police officer murdered George Floyd, a Black man who had been shopping at a corner store. Black Lives Matter protests brought a record number of Americans into the streets, and organizers ushered in a national conversation about police budgeting, use of force, and accountability. Cooper said that, at the time, the media was able to “at least articulate the demands of the people.”

In the wake of the 2020 uprisings, the journalism industry began to have public conversations about the ways in which standards of reporting needed reevaluating.

For instance, the media nonprofit Free Press argued that the media itself should defund the crime beat. In an op-ed for NiemanLab, Free Press staffers Tauhid Chappell and Mike Rispoli wrote, “While crime coverage fails to serve the public, it does serve three powerful constituencies: white supremacy, law enforcement, and newsrooms—specifically a newsroom’s bottom line.”

In other words, platforming police is good for sales and harmful to already marginalized Black and brown communities. Criminalization and climate change go after the same communities, and it’s the same communities used as clickbait that are also most likely to live near polluting facilities and pipelines.

The call for the media to reexamine relationships with police and to question what gets defined as crime is proof to Cooper that media can treat activists as newsmakers and offer critical coverage of police violence. It also means that in the context of reporting critically on police responses to climate protesters, it’s not a question of media ability. It’s a matter of willpower.

The result, Cooper said, is a kind of “respectability reporting,” where an article paints the facts of an event without offering critical context that might help a reader understand why someone is protesting.

“[If] I’m trying to get to work, and you’re laying down in the street, I’m going to support a law that allows me to hit you because you won’t get out of my way [and] because I think climate change is a silly thing to be protesting,” Cooper said. “Without context … the media is actually creating an environment where violence against protesters is being justified.”

In other words, platforming police is good for sales and harmful to already marginalized Black and brown communities.

The other risk is that the public begins to see wrongdoing through a criminalizing legal lens rather than assessing if harm has actually been done. Whether it’s locking down on fossil fuel equipment (trespassing on private property), blocking an entrance to a federal building (incommoding), or coordinating a bail fund (for which organizers were charged with racketeering), a reader might see the arrest charge as a lesson in how to feel about the protester’s action.

“If you have implicit trust of the criminal justice system, you would think or it would feel very logical to say, if a person got arrested, they did something wrong,” McCormick said. “And activists get arrested an awful lot.”

Providing valuable instruction to people

There are manifold reasons journalism upholds the status quo rather than questions it: an obdurate broadcast news echochamber that preferences ratings as a primary metric of newsworthiness, a shrinking print journalism landscape struggling with smaller staffs and less funding, a legacy of reporting that has largely disregarded global warming as cause for existential concern, to name a few. Old-guard mentalities about what journalism should do and whom journalism should serve have gotten in the way of journalists fulfilling what should be the goal of reporting: holding power to account and providing information to the public that allows readers to make informed decisions.

As articulated in the NiemanLab op-ed, the media has the power to shape perspectives of public safety as much as it reports on what laws are crossed or what crimes are committed. But the federal government’s role in climate change, including subsidizing fossil fuel companies, denying climate science, and refusing to let the facts play out in court, portends the greatest threat to our individual and collective safety—possibly ever. Media shapes our perception of where danger comes from, who we should be afraid of, and who is trustworthy.

Media lives in conversation with other systems of power yet seems hamstrung by its own antiquated values of objectivity and balance. Looking in from the outside is a way that the media distances itself from the subjects it reports on, but that positioning so often leads to inaccuracies.

“Media’s response to activism is intrinsically tied to who [is] in the media,” McCormick said, noting that the field is still overwhelmingly white and male, a trend also seen in whose voices and expertise journalists choose to platform. A recent Media Matters study from Cooper and his colleague Allison Fisher found that in corporate broadcast coverage of climate change, 52% of segment guests were white men, while just 10% were women of color. Newsrooms themselves are less diverse than the country’s workforce as a whole. Journalists of color remain those hit hardest by newsroom closures and layoffs.

Outside of newsrooms, white people are least likely to see protest as effective and least likely to experience structural or interpersonal racism. Those most affected by flooding, extreme heat, and air pollution are Black and brown families living in redlined neighborhoods, Latinx farmworkers living in unincorporated communities, and BIPOC families living near highways that cut through their neighborhoods in an effort to connect the suburbs to the cities.

Yet mainstream media clings to the idea that reporting is about truth, and it does so without accounting for the lived experiences of the largely white, male, and college-educated reporters that keep them from seeing clearly the criminalization of climate protests.

“We’re trying to draw attention to the deep corruption and greed that’s underlying our system that’s led us to this point, and then the media wants to ‘both-sides’ it.”

This kind of reporting frustrates Carol Spring, a volunteer organizer with Extinction Rebellion who supported water protection efforts at Line 3. “We’re trying to draw attention to the deep corruption and greed that’s underlying our system that’s led us to this point, and then the media wants to ‘both-sides’ it,” Spring said.

She explained that a reporter will seek a quote from a protester, then turn around and ask the corporation for a quote, which are nearly always spun to parade the project as economically necessary or environmentally friendly. Spring said it’s journalistically negligent not to include context or fact-checking of corporate talking points.

Reaching for fair and balanced reporting might be a more accurate way of making the news. Rather than chasing “truth,” freelance climate reporter Elyse Hauser thinks of her work differently. “I would think of journalism as less about truth [and] more about knowledge,” Hauser said. “It’s almost like you’re teaching something. You want to provide valuable instruction to people so that they can go out and use it.”

The most underreported climate story of all is not what climate protesters are against, but what they’re for, said Spring. When she was at Line 3, Spring said the work wasn’t just about shutting down a pipeline, but “creating a different way of being in the world, [a] different way of being in relationship with each other.” She realized that, through the mutuality of care, interdependency, and organizing, “we can create the alternatives that we want to see.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.