Groundhog Day for the Fed

Market forces are colliding as another U.S. financial crisis brews. Meanwhile, sit tight on the roller coaster. A sheet of newly printed, uncut $100 bills is inspected at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing Western Currency Facility in Fort Worth, Texas. (LM Otero / AP)

A sheet of newly printed, uncut $100 bills is inspected at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing Western Currency Facility in Fort Worth, Texas. (LM Otero / AP)

Groundhog Day is Feb. 2. As tradition has it, Punxsutawney Phil pops up from his burrow, wiggles his nose, searches for his shadow and then, if he sees it, casts his prediction for six more weeks of winter (he did see it this year, by the way). But something overshadowed his shadow-seeking expedition this Groundhog Day: the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) Index shedding an eerie 666 points.

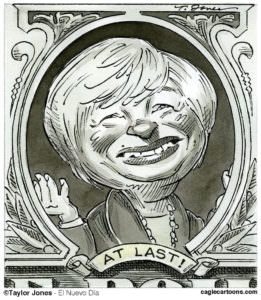

Feb. 2 also marked the final day of Janet Yellen’s reign as chair of the Federal Reserve. Upon her departure, she levied some parting words on the overstimulated markets for incoming chair Jerome Powell, her erstwhile No. 2, as she headed for her plum post as distinguished fellow in residence at the Brookings Institution.

After leaving the Eccles Building for the last time, she mused about market valuations to CNBC, “Well, I don’t want to say too high. But I do want to say high.” (She also said commercial real estate values were “quite high.”)

“Now, is that a bubble or is it too high?” she asked. “And there it’s very hard to tell. But it is a source of some concern that asset valuations are so high.”

Then—bam.

So was that a dare to her successor? A challenge after her years of stock market rallies on the back of cheap-money policy? Or a sign to Wall Street to test Powell and make sure he remained aware that big bank trades, CEO bonuses and share buybacks depend on cheap money?

Or all of the above?

Never underestimate a woman scorned or a financial system facing reduced liquidity. But by the time the Dow had shed its 2018 gains, it was probably clear to Powell—though he didn’t say so—that the decade of cheap money crafted by the Fed, and dispersed through collusion among the world’s major central banks, is more powerful than any new head of any one central bank. More volatility will characterize this year, but these major central and private bankers will have one another’s backs. That means the global status quo of cheap money turboboosting the financial markets will continue, Elon Musk rocket style. It’s all these central bankers know.

Yellen’s Fed

At the helm of the Fed, Yellen kept the course set by her predecessor, Ben Bernanke, in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-2008, albeit with some minimal interest rate hikes mixed in. The federal funds rate (the rate banks use to lend to each other) remained at 0 percent from December 2008 through December 2015 during the transition to her tenure.

This unprecedented intervention that had begun under the “emergency” measures clause of the Federal Reserve Act was executed under the guise of fixing the economy. The S&P 500 tripled from its March 2009 bear-market lows, while wages did nothing of the sort.

In late 2015, the Fed increased the federal funds rate by 25 basis points (the smallest possible incremental change) to range between 0.25 percent and 0.50 percent. Since then, the federal funds rate has been raised four times, to today’s range of between 1.25 and 1.50 percent. At the end of 2017, the Fed forecast another 75 basis points of tightening, which would put the federal funds rate at 2.00-2.25 percent by the end of 2018.

In October, the Fed also announced it would start to shrink its $4.5 trillion book of assets grown under the process called quantitative easing, or QE, which also saw average global rates maintained at 0 percent. The Fed did this by not reinvesting interest payments in more bonds—the least active way of shrinking a book.

In practice, that reduction, given the size of the Fed’s book, has been unnoticeable, despite the associated promise that it was a sign the economy was growing and the decade-long artificial stimulation experiment had apparently—finally—worked.

Markets Find Calm From Central Bank-Speak

In his new job, Powell was visibly absent from the media regarding the volatility-filled second week of February. The week marked the worst in the past two years for U.S. equity markets.

On the surface of the prevailing stock market bubble, investors and speculators worried about inflation and related bond yields rising (or bond prices falling) causing the drop. In reality, these agents were concerned that, maybe, the cheap-money period was coming to an end. But every time this concern has appeared during the past decade, central bankers orchestrate a confluence of events to alleviate the fear. This instance was no different.

This doesn’t mean a financial crisis of greater magnitude isn’t brewing. It is. But central bankers will fight like hell to avoid it, using the only weapon in their arsenal: an unlimited, unregulated and unchecked ability to fabricate capital for the financial system.

Looking at it that way, Wall Street was implicitly daring Powell to reconsider any possible predispositions he might have had to more aggressively raise rates or embark on too acute of a tightening policy. The pervading reason for the market sell-off, or “correction,” was that inflation was rising, And that would precipitate faster rate increases.

Indeed, the first week of his term was bloody. The S&P 500 shed 5.2 percent, its steepest slide since January 2016—a slide that happened to be predicated on a Fed hike in December 2015, the first since the financial crisis. At one point last week, stocks were off 12 percent from recent highs, but then a Friday afternoon rally boosted the DJIA 1.5 percent higher by the end of the day. In the Treasury market, 10-year yields, at a four-year high, ended the week at 2.85 percent, near where they started.

Cheap Money Hasn’t Worked for Main Street

The markets (read: big banks) got upset that their flow of cheap money might dare come to an end. Yet the stated goal for this money flow, boosting the overall economy, hasn’t been achieved, except in the eyes of politicians, central and private bankers, and people blind to the correlation and causation of cheap-money policy with asset bubbles. Even the rumored concern in the market that the economy was somehow heating up so quickly that it would warrant faster hikes wasn’t based on reality. The gross domestic product (GDP) for the fourth quarter of 2017 wasn’t anything to write home about. At 2.6 percent annual growth, it was even 0.3 percent lower than analysts’ expectations.

Then there are actual people, referred to by economists and for GDP purposes as “consumers.” Consumer spending represents about 70 percent of GDP. (I’ll get into whether GDP is a good measure of economic strength in a later piece.) But regardless, consumers aren’t actually doing well across three core areas that reflect a true picture of their ability to spend money to “grow” the economy.

The first pillar is income and wages. On that score, fourth-quarter real disposable personal income grew at only a 1.80 percent annual rate, with 80 percent of workers seeing flat-to-declining wage growth.

Besides making money, there’s saving money. In January, the U.S. savings rate fell to 2.6 percent, or near its lowest recorded levels in seven decades. The only other time it hovered so low was before the 2008-2009 recession.

Then, there’s credit card debt. Over the last four quarters, it has increased by about 6 percent annually, three times faster than during the years after the financial crisis and double the increase in income. People are keeping up with expenses by sinking into more debt.

In all, GDP rose by 2.60 percent in the last quarter of 2017. Adjusting consumption by credit usage, that increase was more like 0.71 percent.

So the promise of central bankers that their policies would help real people is an empty one. This won’t stop them from perpetuating those policies.

Wall Street Doesn’t Want Any Major Tightening

Jerome Powell had a bad first day, being sworn in on Feb. 5. The Dow executed its worst percentage drop since 2011 and largest daily point drop ever. The reason most cited by business news outlets was “fear” of rising inflation, even though inflation isn’t on a significant upswing. The core inflation rate year on year was 1.8 percent, still below the Fed’s 2 percent target. (Fed officials have discussed raising it as well, which would give them more room to ease monetary policy again if needed.)

But panic set in. It coincided not with a new inflation figure, but with Powell’s assuming his post as Fed chair. Wall Street wanted to make it clear that it needs its cheap money supply.

As has become the pattern over the decade when markets freak out because of some pervading fear of what the Fed will do with their money opiate, other Fed officials or major central bankers race in to calm the waters. William Dudley, president of the New York Fed, dismissed the stock market’s drop as “small potatoes” relative to the gains it has racked up of late. Charles Evans, president of the Fed’s Chicago bank, who didn’t want a Fed hike at the last meeting, said he would support “three or even four” rate increases this year if—and remember that “if”—inflation really is moving up. To Wall Street, this implies wiggle room for fewer hikes than forecast.

Around the world, central banks espoused soothing words to curtail selling. Because Japanese government bond (JGB) prices were also cratering, alongside U.S. Treasury bonds, the Bank of Japan announced “unlimited” buying of long-term Japanese government bonds, the continuation of the policy the BOJ already has in place, but the first time in half a year that the BOJ has intervened to buy bonds rather than await regular auctions.

Over in Europe, on Feb. 5, European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi told a European parliamentary hearing in Strasbourg, France, that the ECB can’t yet “declare victory” in its fight to resurrect inflation. To calm financial markets, he noted, “Monetary policy will evolve in a fully data-dependent and time-consistent manner.” That means more central bank intervention to bolster markets when they buckle.

One of the most powerful central bankers, Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, which influences currency baskets and overall monetary policy, stepped in to soothe the markets, too, after an optimistic gathering in the Swiss resort town of Davos of the elitist elites. Speaking at a later elite business conference in Dubai, Lagarde said, “I’m reasonably optimistic because of the landscape we have at the moment.”

The markets happened to dive right after the financial elite congratulated themselves in Davos for their growth-oriented achievements. That optimism only served to inflate market volatility and a downturn. So they dialed it back.

“I’m ringing not the alarm signal, but the strong encouragement and warning signal,” Lagarde said.

And, yes, that is saying two different things at once. To punctuate the success of their policies, she repeated the recent IMF forecast: The global economy will grow 3.9 percent in 2018 and also in 2019. Though she wasn’t oblivious to a potential lurking crisis, she did try to shift blame for any possibility of one from central bank monetary policy to anything else. So she said, “We need to anticipate where the next crisis will be. Will it be shadow banking? Will it be cryptocurrencies?”

Translation: Central bankers don’t have a clue what to worry about, or what to do about it. They create bubbles directly and indirectly. They will keep doing that as long as they can.

Shrugging Off the Downturn for Now?

On Monday, the Dow rose another 410 points, or 1.7 percent, following a strong end on Friday. Tuesday brought more volatility, but nothing like the previous week, when the markets ended up.

This is what’s weird. Rumors last week were that inflation and resulting rate increases were crushing share prices. So are we to believe that suddenly the inflation that was going to happen decided not to occur? Of course not, because it wasn’t the real reason to begin with. There’s a fight going on—between what markets want from central banks and manifestations of true growth in the wider economy.

Companies that hoard cheap cash or debt to buy their own stock look good on paper, and the real economy needs more people with more equitable financial profiles to function in a more stable manner. Current market turbulence represents the reality of central bank collusion to keep a cheap flow of funds to big banks and their corporate clients meeting the lack of true growth or realistic corporate evaluations.

Another financial crisis will happen. It’s a matter of when. But meanwhile, this battle will continue, punctuated by erratic swings along the way.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.